|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions Stamford Church Trail (Various) Kingston on Soar (Nottinghamshire

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

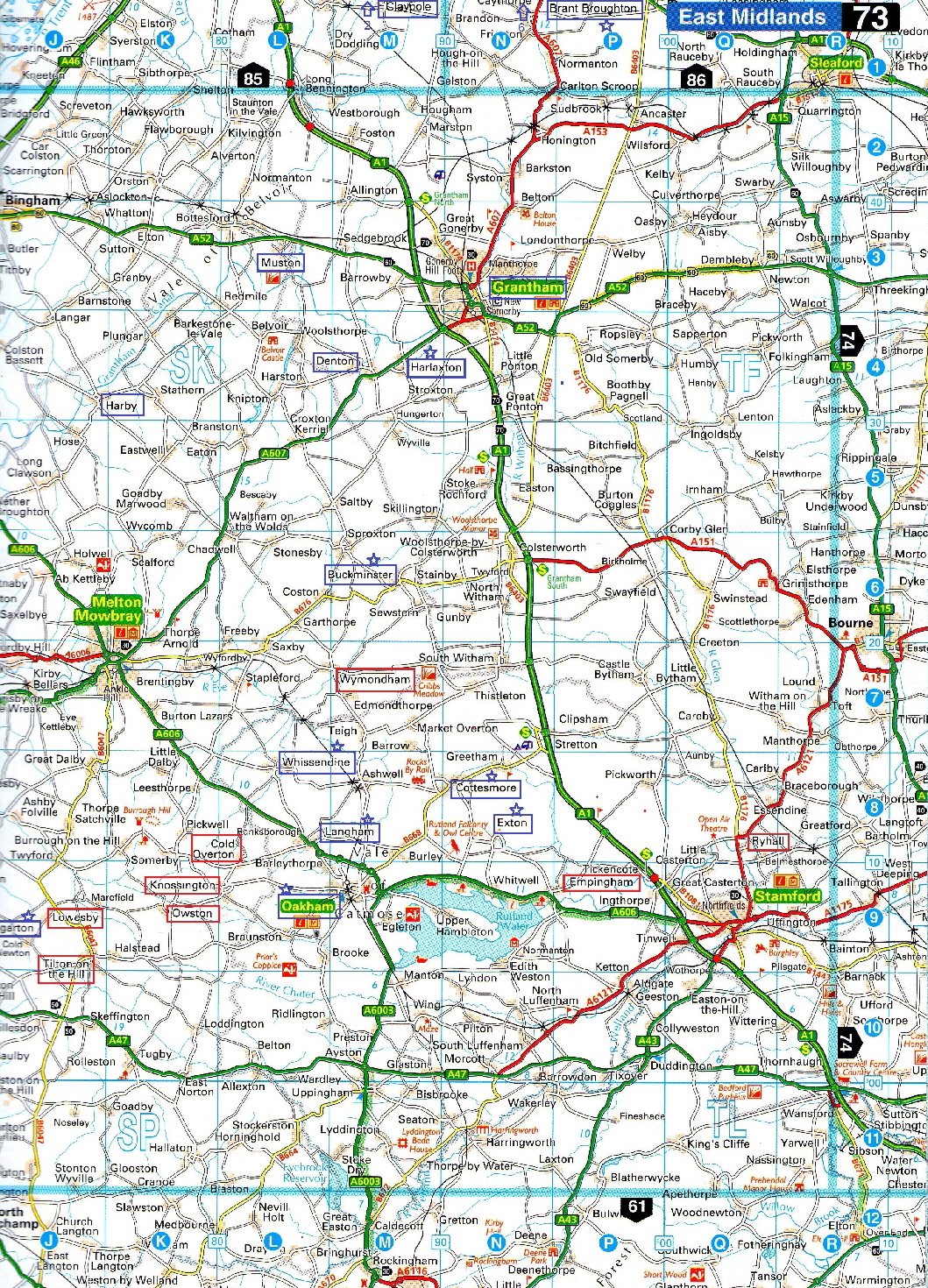

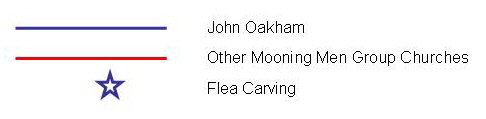

We have explored the existence of a group of masons - the Mooning Men Group - plying their trade very much in the way of a modern company around a geographically limited area of the East Midlands. Everything we have discussed has emphasised the collective nature of their operations. I have defined the churches by the trademark of the mooning man frieze carving. Within that group I identified a subset of eight churches that also had a carving of a flea - if that indeed was what it was - and have suggested that it was the mark of the man I call John Oakham. John had a distinctive sculptural icon that I characterised as being half cow, half lion and that was his style of choice at Oakham, Whissendine and Exton. At five other “flea” churches he apparently created much less distinctive, not so say somewhat boring, friezes - Cottesmore, Langham, Buckminster, Harlaxton and Hungarton - probably in conjunction with an acolyte I called Simon Cottesmore. The mooning men appear in a very limited geographical area and I have suggested that individuals within the group probably came and went according to whether the work was within what they regarded as sensible travelling distance of their home villages or towns. We cannot know, of course, whether their building activities were confined to this area but we can say that their decorative sculpting activities were. I have to been unable to find any sign of Lawrence, Ralf or the Gargoyle Master outside this area. John Oakham, however, was very different. He carved at several more churches, stretching, as we will see, as far as Boston and Leverton in Lincolnshire, nearly fifty miles from Oakham. He did not use the mooning men motif at any of these other churches - although he deployed other forms of exhibitionist sculpture - but he did leave four other flea carvings at Brant Broughton, Swineshead, Harlaxton and Swineshead. I have included Harlaxton within the MMG in my discussions so far but that was only because of its geographical proximity to the other churches. In the absence of a mooner carving it strictly speaking belongs to the likes of Brant Broughton as an extension of John’s activities outwith the Mooning Men contracting group. If the flea demands we recognise John’s presence at Brant, Harlaxton, Leverton and Swineshead , that is by no means the end of the story. We will look at some other churches where with varying degrees of certainty I will conclude John also probably carved without leaving flea carvings. I hope to show that where he did not do so the reason was probably the absence of Simon Cottesmore, his colleague, son, trainee or whatever. Whether you choose to allow all of those bodies of work to have been in whole or in part by John will be a matter for yourselves! So let’s have a look. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Flea Carvings at (left to right): Brant Broughton, Harlaxton, Swineshead and Leverton. Consistent design was not a quality valued by mediaeval craftsmen. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Brant Broughton |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Brant Broughton (this church has its own page) is over 30 miles north of Oakham - the centre of gravity of the MMG - and twenty three miles north of Harlaxton. It is John’s masterpiece. Even the flea carving is more elaborate here than elsewhere. The parapets are crowded with frieze carvings and every pinnacle and buttress is covered with larger one-off carvings that were probably sculpted by John as well. The cow-lion is much in evidence. The frieze, however, is a masterpiece of imagination and is far more varied than John’s equally extensive cornices at Oakham. The stylistic parallels, however, are obvious. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Top Row: Typical cow-lion faces at Brant Broughton. Bottom Row: Greater flamboyance in other Brant Broughton Carvings. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Harlaxton |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

At Harlaxton the picture is very different. It is on the flush gargoyles that we John’s cow-lion imagery. See its own page by clicking here. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Flush Gargoyles: Harlaxton Church. We see here how elusive styles can be on larger carvings. The image on the far left could be straight out of the Brant Broughton or Oakham play-books. The others show different characteristics in particular in the area of the eyes. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Above and Below: Lengths of Frieze carvings, Harlaxton Church Tower. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Harlaxton has only a tower frieze. It is nothing like the one at Brant Broughton but it is similar to other friezes within the MMG area where John Oakham and Simon Cottesmore were apparently working together. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Second Left: Two label stop ladies with the goffered caul headdress. In the example on the left John Oakham has reverted to the realistic carved eye forms that can be seen at Brant Broughton. Centre: Exhibitionist label stop carving, Harlaxton. Second Right and Far Right: Exhibitionist label stop carvings, Denton Church. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Denton |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

John Oakham carried on using the goffered caul headdresses at Harlaxton, confirming it as a stonemasons’ habitual style rather than as a trademark. He used a different form of exhibitionist (see picture above) that was arguably even ruder than the mooning men. What is more he used it as a label stop on a chancel window. So much for the idea that the masons needed to be discreet about these things! And then he used the same form of exhibitionist - twice at Denton only a couple of miles away. At Denton we see the same characteristic flush gargoyles. Like Harlaxton. Denton has only a tower frieze but the style here is quite different. And at this church there is no flea carving. For my page about the church click here. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Flush Gargoyles by John Oakham at Denton Church - and some very modern pipework! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sections of Frieze, Denton Church |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The frieze at Denton has no similarities to the one at Harlaxton so there is no sign here of the work of Simon Cottesmore. It is not much like John Oakham’s own work within the MMG. So we are perhaps seeing evidence of a temporary collaborator. And we are going to see this style again at Claypole and, less obviously, at Grantham. As at Harlaxton, far from abandoning the ubiquitous goffered caul headdress, John used it very conspicuously as a label stop device. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Muston |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Seven miles from Denton is Muston Church and here we see the unexpected site of a baptismal font very clearly manufactured by John Oakham who uses, we might say incongruously, a plethora of his cow-lion carvings. Commonsense tells us that the MMG masons must have carved inside churches as well as outside but this is the clearest evidence we have. As at Denton, there is only a tower frieze and also as at Denton the carving is not obviously attributable to one of the “named” masons. Nor does it look like the work of the frieze carver at Harlaxton. Harlaxton, Denton and Muston all have interesting displays of label stops, including on the clerestory windows which within the MMG is a conceit only seen at Ryhall. Muston also sees a range of labels that are probably life-like images of masons. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Lady with goffered caul headdress, label stop, Denton Church. Centre and Right: Baptismal font, Muston Church |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Lengths of tower frieze, Muston Church |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Muston Church: Heads with goffered cauls and probable representations of stonemasons. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

As at Denton, Muston Church has no flea carving. It is surely, though, patently obvious that John Oakham was the main sculptural mover and shaker here at this group of three churches. Along with Brant Broughton, then, we have identified four churches outside the MMG at which John indubitably carved. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Claypole |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Claypole has a profligate collection of sculptures. It does not manage (with one or two exceptions) to come anywhere near the standard of Brant Broughton. Its long friezes confound us by not being of a style seen anywhere else. There is no flea, no mooner. Surprisingly, there are no signs of goffered caul headdresses outside the church either - but, as we will see, there are some inside, Two things, however, put this church into the John Oakham nexus. One is the tower frieze that is very obviously by the same man who carved the tower frieze at Denton. The second is a label stop exhibitionist that is very like those at Denton and Harlaxton. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||

|

Sections of Tower Frieze, Claypole Church. Compare it with the pictures of Denton tower frieze above, |

|||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sections of Clerestory Frieze, Claypole Church. These are friezes packed with animals and whimsical representations of people which makes them different from any other frieze within this study in subject matter as well as in style. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

There is a lot to interest us at Claypole. Above left is the male exhibitionist very much in the Harlaxton/Denton style. There are many very good labels stops (examples top centre and right) that are, I think, contributions from John Oakham himself. I have remarked on the lack of goffered caul headdresses on the friezes. Instead there is a are a few examples of women wearing wimples. Women’s headwear fashions are a minefield (especially for a man!) but we know that the wimple probably originated in the east and “discovered” by the Crusaders. No respectable woman of any class - especially a married woman - would be seen outside without her head covered and the wimple offered a simple solution that, unusually, could be used by any class of society, although the quality of the material varied very greatly. What is interesting about these examples is that the women in question have used veils to cover their faces. This is something that women were known to have done but, in fact, it is very common in depictions of the style at churches throughout the country so perhaps the masons are giving us an insight into how much of a preoccupation modesty was to mediaeval women. The style was found throughout Europe, was very long-lived and only disappeared at the beginning of the sixteenth century. In the top row second right we see another type of headwear. This looks like a heart-shaped headdress such as was seen from around 1405 onwards - neatly fitting with our Mooning Men Group time frame. It looks a rather simplified version such as we might expect from a mason who might, anyway, have seen very few examples of high-status headwear on his travels. Last but not least, we may see no goffered caul headdresses outside the church but we see a real handful of them inside. Some are used as internal moulding stops (middle row right and second right) and best of all, there are two on superb triple sedilia which is the pride and joy of this church. Not only that but one of those is wearing a crown and accompanies a king. The queen, however, and two others - but, oddly not the king - have been defaced. Why? I have a theory. Consider these points, Firstly, defacing a monarch’s face has no basis in religious doctrine - it was not a casualty of the Reformation for example. Secondly, it would be a seditious thing to do and thus very dangerous for the perpetrator. Thirdly, why deface the queen’s head and not that of her husband the king? What queen’s head could be defaced with impunity? Well, the headdress itself gives us the possible time frame. Almost certainly the king is Henry IV who deposed Richard II to seize the throne in 1399. Surviving portraits show him to have been bearded whereas his son and successor Henry V was clean-shaven. His predecessor Richard II (also unbearded) is generally regarded as one of England’s worst kings but there was no reason for anyone to deface his wife but leave him intact. We are surely looking at Henry IV. He married twice. His first wife was Mary de Bohun and by all accounts they were devoted to each other. She died young, however, and Henry married again to Joan of Navarre who survived him. It seems that was a love match too. Henry died in 1403 and was succeeded by his son as Henry V. Under Henry V Joan was appointed Regent during Henry’s early absences in pursuit of his favourite pastime of slaughtering large numbers of Joan’s fellow countrymen. After Henry’s return there was a falling out and Joan was accused of plotting to kill her husband. She was never tried but she was stripped of her properties which Henry was conveniently able to use his fund his next military expedition. She was imprisoned in some comfort at Pevensey Castle and then Leeds Castle. Henry released her six week before his death. What is startling is the means by which Joan had supposedly plotted to kill her stepson. It involved “sorcery and necromancy”. This, surely, is the mysterious defaced queen. In the puerile language of today’s society Joan of Navarre was “cancelled”. Faces of another woman and a man have also been defaced, possibly members of Joan;s family (she had no children with Henry but several by her first marriage to Duke John IV of Brittany). The king and the bishop to Joan’s left are a little damaged but not obviously defaced. The headdresses inside the church - as well as those to a lesser extent at Muston and Denton - reveal the full picture of this headwear as worn by the wealthy; its veils and folds and decorations. This is a much fuller depiction than the flat lifeless imagery of the MMG friezes. The Claypole imagery does confirm better than anywhere else that this was indeed the headwear of the rich and I think we might reasonably conclude that it was far more prevalent than the various costume histories depict. We cannot know whether the sedilia and the external sculpture were contemporary. We also can’t know how much of this carving was executed by John personally. We can only be more or less sure that he was there and that the exhibitionist was surely his. I rather doubt whether John (or any other mason) had seen Joan of Navarre in picture or in person so it is quite likely that he dressed her in the headwear style he used for all of “his” women. I strongly suspect that the sedilia was indeed carved by John. |

|

|

|

Grantham is north of the MMG area but is close to the John Oakham sites Harlaxton, Denton and Muston. The church is one of the largest and finest in the Midlands and it is not at all surprising that it has quite a lot of decorative sculpture although unlike, say Bottesford, the quality here is pretty ordinary. There are friezes and once again we can deduce from a number of goffer caul headdress heads that some of this work was during the same period as all of the other churches we have discussed. Another intriguing little thing is a discreet (for once) exhibitionist carving on the north aisle frieze that is of the same design as the much bigger label stop exhibitionists at nearby Harlaxton and Denton. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

It is hard to know where to start with Grantham’s friezes. It is a large and complex church that has seen many phases of development. The north side has the more vibrant designs. The top three rows are in quite different style to the fourth and fifth rows below them. Those three have an interesting proliferation of wimple headdresses, supplanting the goffered cauls seen so often on the MMG/John Oakham sites. The comparative serenity of the female faces contrast with the many tormented mens’ faces. It is by no means clear that they were all carved by the same man. The fourth and fifth rows show a more consistent style that is less belligerent but with much more varied symbolism. On the sixth row is yet another different style on the north side. This frieze is badly weathered but it is more reminiscent of the styles found at John Oakham group of churches. Overall, however, you would need a strong imagination to see much on this side that makes MMG/John Oakham jump out at you. On the south side things become even more complicated. In that bottom picture we can discern at least three different sculptors and two of these styles are reminiscent of some MMG sites. The carving to the left of the queen even has a distinct similarity to the work of Lawrence of Leicester. It seems that the sculpting here was something of a free-for-all. Take note here of the design of the crown on the queen, Note also the men with heavily wrinkled brows, |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Second Left: There is another goffered caul figure on the south side of Grantham and you can see obvious similarities, principally in the way the crown is formed. Note too the carved septum in the nose. And note the small down-turned mouths, giving them a somewhat supercilious air. Now look at the next picture (Centre). You can see the same way of carving the crown and that down-turned mouth is there again. The nose has been broken, destroying the septum. The faces are rather different in shape but they clearly are stylistically the same. That picture centre is not from Grantham, but from Harlaxton! The two right hand pictures, however, are from Denton. The left hand Denton picture (second right) has been damaged but you can still see the similarities in the eye structures. Then in the far right hand picture we see a rather more glamorous face but still with that haughty mouth. I have already established that Denton and Harlaxton are John Oakham churches. It seems nearly certain that he was at Grantham too. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Second Left: Two more label stops from Harlaxton. Compare these with the drilled hole faces shown on the Grantham frieze above. Second Right::The Grantham exhibitionist . He is in the pattern seen at Harlaxton, Denton and Claypole. Right: Another goffered caul at Grantham. |

|

|||||||

|

This is a section of the tower frieze at Denton. The tower frieze at Claypole is in very similar style. The eye structures are very similar in style to two of the label stops at Grantham. |

|||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Finally, a comparison between a frieze carving on the north side of Grantham (left) and a label stop from Denton (right). These dog-like faces are clearly not the same. But if you look at they eyes, nose and mouth they are clearly carved by the same man! |

|||||||

|

Grantham is a somewhat disobliging place when trying to track John Oakham’s peregrinations. The friezes are a muddle and there is no mooner or flea. For a long time, despite its proximity to Harlaxton and Denton, I resisted the notion that John Oakham might have been carving at Grantham. Closer examinations, however. lead me to the conclusion that John was indeed at Grantham. There are just too many little clues that when looked at together add up to a big clue. There is plenty here that may well not be his work and we cannot know in what capacity - but I am sure that John Oakham wuz ‘ere. |

|

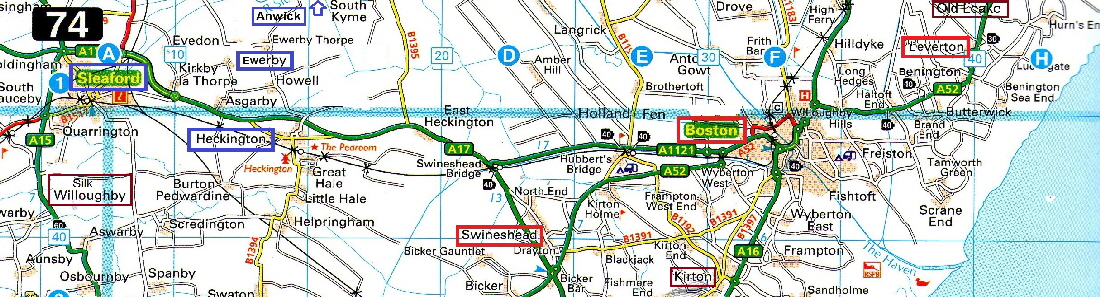

Swineshead |

|||||

|

Swineshead is well over thirty miles from Cottesmore, so it is another radical departure from the MMG’s stamping grounds. It is only seven miles from Boston, the original port of departure of “The Mayflower” and, as we will see, John was there too! At Swineshead we can see John’s hand all over the sculptures and on this occasion we can confidently identify his inimitable style inside the church. There are also two large flush gargoyles, one of which is certainly a pig and the other of which might be a pig. I took this to be a little joke about the village name on the part of the masons and/or the patrons. The Church Guide pooh-poohs that idea announcing somewhat sniffily that the village name derived from the Anglo Saxon words “swin” for a tidal creek and “heda” for a landing place. Well, yes, I am sure that is right. So, it’s a coincidence, then? Myself, I think there is a very good chance that the mason had a rather more developed sense of humour than the author of the Church Guide. |

|||||

|

|||||

|

Section of tower frieze, Swineshead Church. The tower frieze has weathered badly - this is one of the better sections! The cow-lion faces are typical of John Oakham but these carvings are “stripped down” versions which compare unfavourably with his more developed designs at Oakham and, in particular, Brant Broughton (above), The presence a John Oakham flea carving alongside these grotesques is invaluable in identifying this frieze as his work as well as similar carvings at Boston (below) where John did not oblige us with a flea carving. |

|||||

|

The friezes on the clerestory, however, are very different. Here we see the kind of frieze reminiscent of Cottesmore: a dense mass of small undistinguished, albeit characterful, carvings and the return of the oval “blind eyes” that characterise that and other friezes that seem to denote collaboration between John and Simon Cottesmore. |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Sections of Clerestory Frieze by John Oakham and Simon Cottesmore, Swineshead Church |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Left: A swine’s head gargoyle, chancel, Swineshead Church. Second Left: Another swine’s head on the chancel? Centre: Label stop by John Oakham (note the eye structure). Second Right and Far Right: Spandrel carvings, interior, Swineshead Church. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

John Oakham Carvings, South Aisle Frieze, Boston Church |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Centre: Flush gargoyles by John Oakham. North aisle. Right: John Oakham carving, North Aisle, internal frieze. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

A picture should be emerging here of a mason-sculptor as the dominant decorator of a while raft of churches both within and without the Mooning Group territory. We are also seeing if not a variety of collaborators then a variety of styles alongside John Oakham’s distinctive motifs. If he was again a part of a peripatetic group of contracting masons we sadly have no evidence of it because there are no trademarks like the mooning man to guide us. We cannot know for certain that he was not himself the contracting mason but as with the churches within the MMG I believe it most unlikely since that role would have been too demanding to allow indulgence in sculptural activities when others were clearly available to do it. At his next location we can be certain he was not the contractor. The rich port town of Boston had begun rebuilding its church that was dedicated to St Botolph and is now universally known as the “Boston Stump” for its inordinately high tower and spire. Its exterior is a mass of sculptural carving and amongst those involved was your friend and mine John Oakham. We will recognise him by his characteristic cow-lion heads on the north side of the church. These are not the sumptuous extravagances of Brat Broughton but more in keeping with the more economical form he used on Swineshead tower. What is more, uniquely, he carved friezes inside the church. The external friezes - and this is true of a great deal of the sculpture at Boston - has suffered grievously. Perhaps it was all the salt in that sea air? Or perhaps a less resilient stone? Either way it is a mess. There are friezes on the south side as well as the north and John might well have been involved in those too but it is impossible to tell. |

|

|

|||||||

|

Left: Further north aisle carvings, showing the richly painted timber mouldings that frame the frieze throughout. It also shows carvings of fleurons that are plentiful on this frieze. Right: A section of the south aisle frieze. Unaccountably, almost its entire length is filled by this style of fleuron. Why? Well, it is very like a Tudor rose in that it has five petals - but is several decades before Henry VII overthrew Richard III at Bosworth Field. A mystery. |

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

Parts of the very long carved frieze on the inside of the south aisle, Boston Church. They are clearly very much the same as the badly damaged external frieze. These are fierce friezes. John has gone in for a lot of gaping jaws and conspicuous fangs. They may look cow-like at Oakham but here they are very much lions, In this more economical form of this type of carving which is very similar to that at Swineshead, the ears are extra conspicuous. The frieze has been painted in some kind of wash that probably has done little for the long term health of the frieze but nevertheless we are seeing it largely as it was carved in the early fifteenth century. |

|

|||

|

Amongst all of the cow-lion carvings John suddenly throws in a couple of domestic pigs to entertain us on the north aisle interior. Did Swineshead give him the idea? |

|||

|

Leverton |

|||

|

I explained in the Preface to this second edition that one of the reasons I had decided to publish the document in web format rather than book format was that I wanted to be able to make amendments and additions. I had been frustrated by finding some churches I would have included had I known about them when the first edition was printed, All of those churches with the exception of Exton are on this page and all involved John Oakham. My decision was justified when on 2 September 2021 I made another foray into the Boston area to investigate half a dozen churches that might have had John Oakham friezes. I kit the jackpot at Leverton. Being six miles to the east of Boston, it stretched John’s range even further, almost to the shores of The Wash. It is worth remembering that in this area John would have been working in the undrained wetlands, a terrain characterised by treacherous marshes streams and drains. This is a frieze of much higher quality than those at Boston or Swineshead. It is found only on both sides of the chancel. It puts John’s work at Boston and Swineshead to shame and approaches the quality of his greatest work at Brant Broughton. Many of the designs are very similar. John’s characteristic cow-lion heads predominate but there is a satisfying array of weird beasts including a splendid salamander. The buttresses are adorned with the grotesque figures so familiar in this part of Lincolnshire and there can be little doubt that John carved these too. John obliged us with a flea carving (see above). It is the umpteenth variation on the theme and leaves us none the wiser about what John was really thinking when he carved them! To the south of the chancel is a small chantry chapel. Both the two buildings and their decoration are clearly of a piece and Pevsner speculates, I am sure accurately, that the man who commissioned the chapel also paid for the chancel. The whole thing is far removed from John’s work within the Mooning Men Group. This has the look of being a comparatively small program of work with John being the sole decorative mason. Whether he was part of the wider building team, as he assuredly was within the MMG, or whether he was employed solely for decorative work we will never know. Either way, this is one of the most aesthetically satisfying of all of the decorative schemes illustrated within this narrative. It has a lovely sense of being complete and bijou and the carvings are still fresh. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

John Oakham’s Leverton Gallery |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

John clearly did all of this sculptural work and it gives us a priceless insight into his style when working away from the physically restrictive canvases of cornice and gargoyle. In style and content it is reminiscent of so many buttress and pinnacle carvings throughout the South Lincolnshire area, not least the elusive “Harlaxton Cluster”. At how many of these other churches did John contribute such work? Go and make up your own mind! Not only is Leverton an exciting story in terms of being the furthest east that John travelled, it is also where we can most definitively say that he sculpted inside a church - something that seems very likely in quite a number of “his churches” but about which it has been difficult to be certain. At Leverton John very clearly sculpted the impressive triple sedilia within the chancel itself. Here John has obligingly sculpted a frieze at the top of the piece his usual array of “cow-lion” heads and fleurons, plus at rather nice female figure with a headdress carved in some detail. John’s other certainty in terms of interior is Muston’s font. That too is distinguished by John’s iconic cow-lion heads. At both Leverton and Muston, what seems perfectly run-of-the-mill as external decoration looks somewhat anachronistic inside a church. Grotesques on sedilia, piscinae, easter sepulchres and the like are not unusual but John seemed to lack the imagination or the ambition to move away from his usual style or to incorporate more imaginative imagery. At the same time, we can see that he could tackle larger pieces of work: his decoration could lack imagination but his technical capabilities are in little doubt. We must also presume that his patrons were perfectly happy with his particular brand of drollery. |

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Above: The triple sedilia with the frieze clearly visible. Right Top Two Rows: Characteristic John Oakham carvings on the sedilia frieze, clearly from the same sculptural stable as those on Leverton’s chancel cornices. Right Bottom: Two large John Oakham carvings on either side of the chancel arch. |

||||||||||||||||

|

For my Leverton page please click here |

||||||||||||||||

|

Welbourn |

|

Welbourn has carvings of remarkable contrast. It has what are surely some of the finest mediaeval musician carvings in England (see them HERE) as well as one of the finest carvings of a mermaid. These are all carved on the buttresses around the south aisle that has late Decorated period windows. Then there is a clerestory with Perpendicular style windows. It has a cornice frieze that is irregular and poorly-carved and but has a mass of goffered caul headdresses! And Welbourn is only four miles from John’s great work at Brant Broughton where he walked away from the goffered caul headdresses altogether. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

|

|||||

|

There are at least three different eye forms here. The label stops and the above-window carvings are equally patchy. I doubt that all of this is by a single mason, let alone John Oakham. Perhaps Simon Cottesmore is responsible. Perhaps John Oakham wasn’t here at all but Simon did seem to be attached to him. The temptation is to conclude that John carved all those lovely buttress carvings and left his sidekick to do the clerestory cornice. The clerestory seems to have been added at least twenty years later, however. A further problem is that where the two were together they left flea carvings. It is the reverse of Brant Broughton where everything was clearly by John yet he did leave a flea! But, of course, we cannot prove that Simon Cottesmore had no role there at all. Go figure! |

|||||

|

Harby |

|||||

|

In 2021 I discovered that the range of John Oakham’s peregrinations extended beyond his previous easternmost limit to Leverton, a stone’s throw from the wash. In 2023 sheer luck took me to Harby in Leicestershire where there is a very interesting tower frieze and - probably - another flea carving. A few miles west of the previous westernmost point of Denton, this established a new westernmost limit. John’s travels were extensive indeed. Whether or not the carving there is a flea is open to some question but I believe on balance that it is. To see my page about the church click here. |

|

||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

Top Left: This is what I believe is John Oakham’s flea carving. It is not like the others but this is not unexpected: not only are all the fleas different but it is not a given that John personally carved them all. We can say that some definitively were - Brant Broughton and Leverton, for example - but others like Cottesmore and Buckminster (both Simon Cottesmore) are Langham (Lawrence of Leicester) almost certainly were not. The fleas simply announced his presence at the site, it seems. Anyway, I acknowledge the ambivalence here. Some of the other carvings shown here are certainly in the style of those found elsewhere in the area. In fact they are better than most, although weathering has taken a significant toll. |

|

Summary and Conclusions |

|

These ten churches are the limit of those churches - apart from those within the MMG - that I will confidently aver had John Oakham amongst their sculptors - although there are big question marks about Welbourn. Even for these I have to confess to some things being unknowable. Harlaxton, Brant Broughton and Swineshead and Leverton have fleas. The other six do not. I had considered the possibility that the fleas denoted the dual presence of John and Simon Cottesmore, given their clear collaboration within the MMG, but John’s obvious omnipotence at Brant Broughton and Leverton scotch that notion. The fleas are priceless in allowing us to see the way in which a mason-carver’s work is not instantly recognisable. That trademarks allow us to identify him at Harlaxton where the sculptural carving does not scream out John’s identity and at Swineshead which is so far away from the MMG that we would otherwise doubt his presence. Muston’s font is very obviously John’s. So are the flush gargoyles at Denton. The feet-behind-the-ears exhibitionists at Denton and Harlaxton are mirrored at Claypole and at Grantham where we would otherwise struggle to pin John down. At Boston we have to fall back on those cow-lion heads and if we had not seen John’s fleas at nearby Swineshead and Leverton we might doubt the evidence of our own eyes. In other words, this is all very hard work! Confirmation bias is a perennial problem. In the first (printed) edition of my book I had placed John Oakham only at Oakham and Whissendine within the MMG and at Brant Broughton outside it. That seems astonishing to me now but at that time I had not found the flea carvings at Exton, Harlaxton. Leverton or Swineshead so there was insufficient evidence for me to make any conclusions about their provenance. They appeared to be just another trademark of the MMG and although I suspected that they were the mark of a single mason it took their appearance outside the MMG to compel a more definitive answer. So what do we conclude about John Oakham’s career now that he has morphed from a relatively ordinary part of a “building firm” active around Oakham to a man that can be pretty well definitively placed at at least fourteen churches? I do not believe there is any reason to re-define his role within the MMG. The mooning man trademark clearly defines a group working under one or more mason-contractors. Let us remind ourselves, moreover, that the absence of sculpture by an individual mason at an individual church does not mean that the mason was not there in any capacity. For all we know John and the others might have been within the team at many more of this group of churches. We don’t know how the mason-sculptor was selected on any given site. I would suggest that the MMG did not as a team work at any sites other than those I have identified simply because I feel that if they had we would still be seeing that mooning man appearing somewhere even if there was no frieze to be carved. I think it extremely likely that some or all of the masons worked under other contractors at other sites. Ralf of Ryhall, Lawrence of Leicester and even the Gargoyle Master would have needed to have work at other churches if they were to have had anything resembling a career of reasonable length. There is no sign that John’s extra-MMG activities were as part of a discrete organised group of masons similar to the MMG. We might stretch a point to say that the “new” exhibitionist found at Harlaxton, Denton and Claypole (and the miniature version at Grantham) is a trademark but, if so, of whom? It seems much more likely that this was John Oakham leaving his own mark rather than it being the mark of a collective. Another big question is on what basis John was at these sites at all? I am confident that the MMG churches were all expanding their aisles and raising their clerestories creating the opportunity to sculpt. This was an opportunity for mason-contractors and their peripatetic teams. It was a thriving and focused group. But outside the MMG we can see no evidence for such teams. It is more likely that John himself was the opportunist, travelling from church to church, offering his services wherever there was work going on in whatever capacity he could. His work at Swineshead is unsophisticated, bordering on the absurd when you compare it with Brant. Boston was awash with carving in a town able to spend big money. John may have carved more - even a lot more - than those long monotonous friezes but it is hard to believe he was the principal much less the sole sculptor. Yet at Brant John was given the commission of his life and seized the opportunity with both hands. There it is hard not see to see him as being in the capacity of “ymaginator”: the man who was there to beautify, not build. At Muston he carved the font: a real eye-opener showing he could turn his hand to most things. It is a real curiosity: a handyman’s font with the same cow-lion sculptures he put on the outsides of churches. The result is an incongruous, even anachronistic, one-off affair that the spiritual heir to all of those many horrendous and child-like Romanesque tympana and fonts that we see where masons stepped outside their competence zones. Indeed, this was surely the lot of Joe Mason throughout England: always looking for an opening, sometimes enduring periods of idleness between jobs, occasionally being packed off to do the King’s work, doing a stint at the quarry, taking what he could get which was sometimes well below his capabilities, and just getting by. Much like many modern builders, in fact! There were sixteen churches John worked on at least. Did that constitute a healthy career? It is hard to judge when we do not know for how long he worked at a site and in what capacity. What I can say, I think definitively, that this is by an enormous margin the most extensive nexus of work ever identified as being attributable to a single mediaeval parish church stonemason. This would still be true even if you discounted one or two churches where his fingerprints are less clear. For my own part, I suspect the size of sculptural his estate is likely to be have been larger rather than smaller than that I have identified. Let us try to make some intelligent guesses about his longevity. Let us assume that I am correct in my inference that within the MMG John was part of the crew and was also used as a finisher. How long would he be at a church? The nearest I can get to making a calculation is from the contract for the total rebuilding of Catterick Church in 1412. This involved building chancel, nave, two aisles and west tower and the whole church was to be built in three years. The next bit is what is interesting: that three years specifically excluded the parapets which were to be completed within another year - as much as a third of the time needed to build a whole church. This is the clearest possible indication that the provision of parapets was no small matter. Catterick is not a huge church and its parapets are conspicuously plain, only the tower being battlemented. This implies that the provision of battlements and a frieze at a site such as, for example, Oakham which is a much larger church would take as much as two years! This is crude and circumstantial but it suggests that a mason-sculptor within the MMG, for example, could easily spend two or three years at a site first as a builder and then as a sculptor. In the case of John Oakham with fourteen churches to his name we could reasonably conclude that he had a quite long career measured in decades rather than in years at a time when injury, disease and overall low life-expectancy would all have been conspiring to cut it short. Another insight obtainable form contracts, by the way, is from that for the leading of the roof Arbroath Abbey. The abbey contracted with a plumber on 16 February 1394 to put lead on the choir and to make gutters. Wiliam Plummer, “Citizen of St Andrews” provided a receipt to the abbey for payment on 21 May 1396, two years later. William had two men working with him. Putting lead on roofs - one of the MMG activities - was another job that, even allowing for the size of the abbey’s choir, was not to able to be done quickly, it seems. Finally, it would be wonderful if we could identify John’s progress; if we could say he was at “Oakham” and then he moved to “Exton”. That, of course is impossible. I think, however, that we might confidently suggest that John Oakham’s work within the MMG pre-dated his work outside it. I base that principally on the quality of the work that he produced at the more far-flung locations of Brant Broughton and Leverton compared with the conspicuously lower quality of his sculpture at, say, Cottesmore and Whissendine. The picture forms of a man who was a mason of the common sort. part of a peripatetic team under the MMG contractor-mason, putting his hand up to do the “finishing work” and developing his skills. Perhaps the culmination of his MMG career was at the important and well-endowed church at Oakham where his friezes are extensive. John had perhaps “arrived” as a sculptural mason at Oakham. Then I think he moved north, probably when the MMG lodge folded through either the loss of the contractor-mason(s) or through a dearth of work. Perhaps he went next to Grantham where he would again have just been one of a few decorative masons. Perhaps from there, with the prestige acquired from working at Oakham and Grantham he made the short trip to Harlaxton, Denton and Muston (although not necessarily in that order). There in what I call the The Harlaxton Triangle he seems to have found his feet as a sculptor to be reckoned with. Friezes now were less important than gargoyles, label stops, and spandrel carvings. At all of these churches he was clearly the principal but not the sole sculptor. At Muston he delights us with his peculiar font. John was a mason building a reputation. From the “Harlaxton Triangle” (and I have still never been wholly sure he was not involved at the sculptural art gallery that is Bottesford) he probably carried on north. It is important to re-emphasise that John was now having to carve out his own niches. He needed to find himself work, sometimes in a role that allowed him to demonstrate his virtuosity and sometimes in one that just allowed him to keep body and soul together. His ability to pick and choose was limited. At Brant Broughton he got his greatest commission and we see the fully-developed John. Here he was surely a decorative mason first and foremost, although doubtless mucking in on the building side too. Welbourn was a low-budget project but we see John flowering again with his superb village orchestra, amongst other delightful non-frieze sculptures. And then he moved east. It is quite difficult to imagine John moving from Brant and Welbourn east towards The Wash without picking up work at the Sleaford Cluster of Sleaford, Heckington, Anwick and Ewerby. The friezes are so much in the spirit of John Oakham but we see nothing to enable us to pin him down and these were surely just part of the frieze-carving tradition of the area. All of those buttress and pinnacle carvings, however - hard to date and allowing considerable artistic latitude - are another matter. We can only speculate. All we know for certain was that he ended up in the Boston area. Perhaps hearing of the great work in rebuilding of the Boston Stump - the mason community probably had its very own “bush telegraph” - drew him there in the near-certainty of employment. Maybe he was already at Swineshead when that opportunity arose. Perhaps the clerks of works at Boston were scouring the area for skilled labour. Surely for John this was an opportunity not to be missed. There he was one of the crowd but got to sculpt some repetitive friezes, including those unusual ones on the insides of the aisles. I think other work was also probably his - see here for some possibilities - but identifying it is impossible. Either way, with involvement in another prestige project under his belt, John then maybe found perhaps his last commission - probably a lucrative one - at the chancel rebuilding at Leverton, a swansong of suitable quality. Then perhaps failing health (there were no pensions back then) or advancing years made him settle in Boston. Or made him return to the Oakham area to his long-suffering wife. Or perhaps John is buried somewhere in the churchyard at Leverton, his tools bequeathed to his son or his nephew, having lived a life on the road. We don’t know his name but we have his legacy. And I am the first person to have noticed those danged fleas! John, mate, it took us six hundred years but we got there in the end! RIP. |

|

||||||||||

|

Catterick, Church, North Yorkshire |

||||||||||

|

John Oakham around Grantham and Oakham |

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

John Oakham East of Sleaford |

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

Recommended Next Section: The Sleaford Cluster |

|||

|

Church Building in the Post-Plague Era The Peregrinations of John Oakham (You are Here!) |

|||