|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Frieze Carving, Gargoyles and Church Construction

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

St Mary’s Church, Woodnewton, Northants. An archetypal English country church with a Gothic exterior concealing a Norman core. |

||||||

|

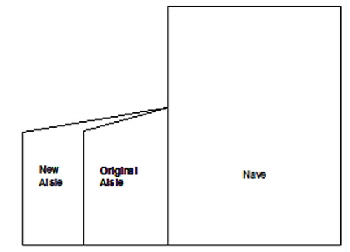

But, this is not how most of them were originally built. Most of our stone churches started out as aisle-less two chamber Norman buildings with just nave and chancel. Maybe a squat west tower if they were lucky. If they had aisles they were narrow with steep roofs. They have evolved to the state that we see now often, if we are lucky, with a Norman core still hidden behind the later architectural accretions. |

|

Before we start, I have to make it very clear that these masons were not building churches. I doubt that they would have known where to start. Most of England’s churches were already built by the time these masons were schlepping around the East Midlands. Most English churches experienced at least three building phases and often four before they reached the form we see today. And that was before the Victorians were let loose on them. When we look at the surviving mediaeval church building contracts - many of them from just this period - you will notice that only one or two refer to building a church as opposed to modifying or extending one. Before we get on to what these masons were doing and why, we need to talk about the Plague itself and of the fourteenth century in general. . The first half of the century saw an explosion of population that combined with some catastrophic harvests to produce considerable famine. There is evidence that even before the Great Plague of 1348 a general surplus of labour was leading to feudal duties being reduced in some areas of the country - as well as a general hunger in the land. Edward III ruled between 1327-1377, one of the longest reigns in British history. He was largely competent but military campaigns and the Hundred Years War were his preoccupations and the badly-weakened country groaned under the weight of taxation to support his campaigns. Richard II succeeded him in 1377 at the age of ten. In 1381 the Peasants Revolt, mainly triggered by a Poll Tax, came close to succeeding in his overthrow. Although blame for that that cannot be laid at Richard’s door, being only fourteen at the time, he is generally regarded as being one of England’s most undynamic monarchs amongst a crowded field of contenders. Militarily incompetent, he presided over reverses in both Scotland and France. “Narcissistic” and “Schizophrenic” are two modern descriptions of his mental state. He was overthrown by the usurper Henry Bolingbroke - Henry IV - in 1399. Richard had made the mistake of alienating the great lords of the land. All of this, though, pales into insignificance against the effect of the Black Death that ravaged Europe between 1348 and 1350. 30-60% of Europe’s population died, depending upon which figures you believe. The best estimates in England seem to be around 40%. That wasn’t the end of it, however: Plague returned at intervals for the next 60 years. The 1361 outbreak was known as "The Pestilence of the Children." This outbreak killed the young disproportionately since they did not have the acquired immunity of those who had lived through the 1348-50 holocaust. It is estimated that the population of England peaked at around four million in the late thirteenth century, fell to around 2.5 million and did not recover until 1601. Everything about the Plague would have had placed a huge damper on church building activity. The masons were not immune and we must assume that 50% of their ranks perished. Parish organisation would have been paralysed by the deaths of local leaders. Church building will have had to accommodate half the pre-Plague population. The local lords may have been able to isolate themselves sufficiently to raise their chances of survival but they found themselves with a feudal labour force that had halved and demand for agricultural products with it. The economy, in short, was in turmoil. Feudal peasants absconded, sometimes to lords that offered better conditions. It would not be true to say that feudalism died during the Plague - its abolition was one of the demands of the Peasants Revolt in 1381 - but it gradually became untenable and disintegrated. Manorial lords found it more convenient and profitable to let their land for cash rents than to work the demesne lands themselves. Without demesne lands to work the retention of serfs was pointless. We tend to focus on the demise of masons when we talk of the effects of Plague on the church building industry. That is to hugely underestimate the impact. We know that the clergy suffered. Many a list of church incumbents has a spike in turnover during this period, and we know that was exacerbated by the survivors’ leaving for more lucrative livings elsewhere. Many churches struggled to fill incumbencies and the quality of priests inevitably declined. It would be easy to forget, however, that the workings of parishes also would have been paralysed by death. Those commissioning and overseeing building work would not have been spared. Parish funds would have been depleted. Rich patrons would have died. Quarrymen and carters, carpenters and labourers would have been equally hit. Royal building projects were not to be interrupted by such trivialities and so quotas of masons were impressed from the counties of England. It was an offer they literally could not refuse. The number of orders for impressment in the immediate post-Plague decades were huge. Work on parish churches must, intuitively, have slowed substantially although with our modern economist hats on we must assume that there were plenty of eager applicants to fill the depleted ranks of the masons. Nevertheless, church building stalled. The only quantification I have seen for the numbers of church projects comes from Gabriel Byng’s indispensable book “Church Building and Society in the later Middle Ages” (Cambridge 2017). He quotes Richard Morris’s “Cathedrals and Abbeys” : “(Morris’s) calculations demonstrate that, after a long period of growth from the mid twelfth century, both the number of projects commenced and the number in progress began to decline from the middle decades of the fourteenth century. In 1220-1350 there was an average of nineteen building projects in progress on great churches each decade and never fewer than fifteen. For the eighty years following the Black Death there was an average of only seven building projects in progress each decade. If the first period was one of uninterrupted growth then the second is on interrupted decline. The nadir was reached in 1430-70 when the average was fewer than three a decade. Indeed, three of the five lowest decade totals for the entire period 1070-1530 are 1430-60”. Byng himself admits that this is a crude measure of activity. And we must be even more careful because these numbers relate to the great churches, not to the parish churches. Nevertheless, it reflects exactly what we would have expected in a post-Plague world and it surely applied at least equally if not more so to parish churches as we must assume that the great churches had greater means than the parishes and were able to offer better continuity of employment. More insight from Byng is in the price of materials after the Plague: “The rise in material prices after the Black Death was, if anything, even sharper than those wages: around double for finished materials in the 1350s and 1360s, However, prices then fell gradually by around a fifth until the end of the fifteenth century except for a slight recovery in the 1430s to 1450s. The rise in raw materials is even greater: around seventy per cent in the 1350s and, after rising in the 1380s to 1390s, peaking at around 150 per cent more than the pre Black Death period....The rising cost of labour and materials after the Black Death probably increased the like-for-like cost of building work by at least double by the early fifteenth century with much of that rise in 1350-75”. Massive rises in costs, demand for agricultural products massively reduced, a shortage of priests and masons, social dislocation and a halving of congregations: the cliched “perfect storm” for church-building then. That, however is not the whole story. Those that survived the Plague inherited land from those that had died. Suddenly, for the first time in English history, some former peasants became considerable landowners. These “nouveaux riches€”, however, were also affected by the population decline and faced the same challenges of labour shortage and suppressed agricultural demand as had their erstwhile masters. Many of the newly-enriched survivors abandoned arable farming and turned to less labour-intensive stock rearing. In particular, they turned to sheep farming. English fleeces were the finest in Europe and had a market overseas. Demand was less dependent on population and the industry was less at the mercy of weather and labour costs. Today we would call it a perfect business strategy. Far from being impoverished and enfeebled by the Plague, therefore, in due course England became steadily richer. The same amount of land in fewer hands had to mean greater prosperity for the survivors. Moreover, history has taught us that free people motivated by ambition will be innovative. After the Plague the fashions in church architecture also changed. The first manifestations of the Perpendicular style were created by the Gloucester School of masonry some twenty years before Great Plague. The aftermath of the Plague saw the Decorated style of Gothic architecture give way decisively to the Perpendicular style. Perpendicular offered a simpler, more consistent style that was more appropriate for the post-Plague recovery period. It also had the advantage of being less bulky and requiring less stone. Perpendicular great churches are often magnificent in style and proportions but there is a uniformity in parish churches about many of the external features, especially window forms. It is no coincidence that at this time we also see the practice of “shop” work emerge whereby window mouldings and the like were carved at the quarry rather than at the building site. Shop work implies more productive – and for the individuals, more profitable - use of skills made scarce by the Plague and is wholly consistent with today’s economic logic. Even if personal wealth started to balance rises in costs, however, it does not explain why churches in the East Midlands and elsewhere should choose to expand when the population had been halved. To understand this we have to look at the post-Plague psyche. If anything is well-documented about the Great Plague it is that the population attributed it to God’s displeasure with those he had created in his own image. In this belief both the humble and the exalted were as one and they had plenty of priests and bishops to ram the message home in their usual sympathetic way. What better way could there be for the wealthy to ensure a satisfactory after-life than by patronising church building? Not only could the endowment of “good works” themselves buy remission but, better still, monks and clergy could be paid to pray for the benefactor’s own immortal soul and the souls of his family. Hence the outbreak of “chantry chapels” within churches built for that very purpose. Some were separate buildings but far more common was to house the chapel, safely behind a wooden or stone screen, at the east end of an aisle. If an aisle did not exist then one had to be built. If an aisle did exist it was likely to be too small. This was quite convenient because changes to the liturgy called for more processions for which wider aisles were a distinct advantage. It is in the widening of the aisles that we begin to piece together a compelling logic for the work of the Mooning Men masons. In order to understand why we need to understand a bit of basic geometry and climatology. So I hope you are sitting comfortably. Aisles built in Norman times or even Early English times, tended to be narrow. There were two very good reasons for this, one related to light and the other related to climate. Glass was expensive in those early centuries and most churches could not afford it. So “windows” might well be of oil-soaked canvas, of horn or of wood. Either way, you wanted your windows to be small so you didn’t get blasted by the elements. Of necessity, however, an aisle would move what little light was coming from the sides of the church further away from the nave. A really wide aisle and tiny windows would make for a really dingy church. So narrowness was an advantage of sorts. Then think about the roofline. A really narrow aisle could have a steep roof. Again, cost would rule out materials like lead in those days. So churches often made do with wooden shingles. You wanted water and especially snow to run off your roof quickly and easily. There was a great deal more snowfall in Britain in the mediaeval period. Standing snow would strain the roof timbers and create ingress problems when it melted. So steep rooflines were advantageous and that fitted in perfectly the idea of a narrow aisle. So when we talk about widening aisles, we can see problems arising. Obviously the windows would need to be replaced. Because the windows would now be further from the nave those windows would need to be enlarged. That was no problem because from the end of the thirteenth century masons were building windows in first the Decorated and later the Perpendicular style and these were much larger, not least because glass - especially “white” glass - was now more affordable. I would note in passing that at this time it was a surprising fact that there was no insular coloured glass industry: all of it was imported and therefore expensive. So widening an aisle might be made light-neutral but if a church wanted to really increase the light, the chances were that they would also want a clerestory. This usually entailed raising the walls of the nave above the level of the aisle arcade and inserting a line of windows. Now for the bit about simple geometry. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

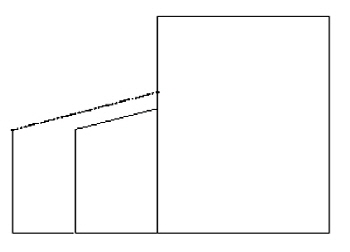

In Figure 1 you can see what happens if you widen an aisle. If the junction between the aisle and the nave wall remains at the same point the roof pitch becomes automatically shallower and, as we have seen, this might not be desirable. In Figure 2 you can see what happens when you widen the aisle and retain the original roof pitch. The junction of the aisle roof with the nave wall is automatically higher. This might not seem so bad, but if you want to have a clerestory as well to help compensate for the width of the aisle then it is a thundering nuisance because you have to make the clerestory that much higher. The shallower the pitch, the higher you can have your new aisle walls without compromising the addition of a clerestory. The answer to shallower roof pitches was, of course, more impermeable roofing material and that meant then as it does today - using lead. Lead sheets were much thicker in the mediaeval period than they are today. Ironically this meant it was liable to “creep” if it was laid at too steep a pitch. So lead and shallower rooflines complemented each other perfectly. As many of the churches in this study had friezes on both their aisles and their clerestories, as well as gargoyles and label stops it is quite obvious that the masons were enlarging aisles, changing rooflines and raising clerestories at these churches. This created the opportunity for the new decoration. Lead might be a very effective roof material but it is also very unsightly. I doubt many homeowners today would welcome it on any other than a flat roof where it would be invisible. Shallower roof pitches were probably seen as desirable aesthetically as well as practically.. Hugh Braun wrote “The High Gothic is based not on high roofs but on high walls carrying roofs that may at times be barely visible...”. Coincidental with the deployment of lead, then, was the widespread use of parapets that effectively hid the aisle roofs from view. It is not difficult to see why this would be so. “Embattled parapets” – those that resembled the crenellations of a castle - became wildly fashionable especially on towers. We are probably so used to seeing embattlement on our village churches today that we would not think how incongruous it is as church decoration. However, for centuries embattlement of a building had required a licence from the King, presumably to restrict the number of strongholds available to challenge kingly authority. It’s first use on ecclesiastical buildings was probably by abbots and bishops, those men of pride who wished to ape their lay peers. As late as 1321 the University of Oxford protested that the parishioners of St Martin Carfax had crenellated an aisle “in the guise of a fortress” to the disturbance of the scholars. Embattlement of a church is decoration, pure and simple, and had nothing to do with fanciful notions of churches doubling as refuges in times of unrest. Quite why it should have achieved such a grip is a mystery. Embattlement required a lot more stone than a simple wall-like parapet, as well as more labour to create it, Within the group of churches I have designated the Mooning Men Group where the masons carved friezes on widened aisles and raised clerestories, Oakham, Whissendine, Langham, Buckminster, Lowesby and Tilton-on-the-Hill all opted for embattled parapets. Only Ryhall and Cottesmore did not. You might reasonably think that crenellations would all be of a quite simple and uniform design but in fact the Mooning Men Group employed - and their customers apparently happy to pay for - a quite elaborate double chamfered style that would have required significant work. All crenellations are not alike. We have records of the church at Orby in Lincolnshire having contracted in 1529 with a mason for the provision of battlements and pinnacles separate from any other building work. The contractor was to emulate designs at two other churches and he was to be paid £12 13s 4d with all materials supplied. In fact the mason, one William Jacson, never even started the work having being impressed into royal works. We can see, however, that the project was totally driven by aesthetic considerations and that the parish were prepared to go to some expense to fund it and that the provision of parapets was not cheap. To put it into perspective, the contract for the construction of a whole small two-bay north aisle for North Biddenham Church in 1522 cost £26, excluding materials. At some churches with wealthy patrons the parapets could be very decorative and often displayed evidence of the patron’s identity. The parapets, of course, would prevent free drainage from the roof. So it was necessary to provide lead guttering and downpipes and/or gargoyles to take away the rainwater that would gather behind the parapets. It could not be allowed to just drain off the roof because it would run down the wall and damage the wall and any mouldings, including your nice new Perpendicular style windows with their fancy tracery. It was to prevent damage to the windows that drip moulds were installed and it was commonplace to put a carving at each end of the moulding. At most churches these were fairly anodyne but one or two of the Mooning Men churches - especially Ryhall - the masons were more inventive. The parapets were deliberately designed to slightly overhang the tops of the walls, again to facilitate effective drainage. The resultant right-angled space was usually finished with cornicing to make it all look tidy. This is where the Mooning Men carvers sculpted their friezes. If you look at all of this as a whole, a remarkable picture emerges of a whole menu of work that the masons were able to carry out. Parishes wanted space for chantries and processions and they wanted more light. The masons would widen your aisles and lower your roof pitch, installing large Perpendicular style windows. Your nave walls would be raised and a clerestory built to provide more light. Your inevitably shallower roofs would be leaded to keep out the water and the masons would hide your new roofs behind parapets that were plain or embattled according to your taste and your purse. Amusing gargoyles and pipework would allow the water from your new roofs to run away and drip moulds would protect your nice new windows from any escape of water down the walls. The masons would put in a stone cornice to make the junctions of your walls and roofs neat and, better still, they would sculpt entertaining figures and flowers on that cornice if you were willing to pay a bit extra You would acquire a carving of a mooning man and maybe a flea as well and you probably wouldn’t know that these were the masons’ trademarks; they would just be part of the fun of the gargoyles and grotesques carved on your refurbished church. Another issue is how the project was managed in terms of the labour. Let us assume (in what is probably a vast oversimplification) this work necessitated structural masons (hewers and layers), setters (of delicate work such as windows tracery), glaziers, carpenters, plumbers and mason-sculptors. If we were looking at work on a single church we would expect the mason-contractor to maximise his returns by employing men only as and when he needed them. For example, he would hardly employ a glazier from the start because that man would be idle until walls were constructed and windows inserted. We cannot be sure how he would acquire this skilled craftsman at the required time but we can safely assume he did not pay him to wait around for several weeks. We can say the same about the plumber. He might be preparing his sheet metal and his spouts and drains in advance of the roof timbers being complete but we would not expect him to be there from the start. And again, we might speculate how the mason-contractor would be sure of obtaining the right man at the right time in the project. We know from the view surviving mediaeval building contracts that they were rarely open-ended in terms of times to complete. This perfectly articulates the problems of the mason contractor when working on a church. He was at the mercy of the timely availability of the necessary craft skills. Academics are oddly blind to this inherent issue when they discuss the building process. So let us look at the modern building industry. A company with a large building site might have its own tradesmen, all mobile with cars and vans. By virtue of their constructing many houses over many sites they can deploy these tradesmen over a whole site or even several sites. Where there are labour shortfalls they might sub-contract or they might already have working relationships with sub-contracting companies that allow them to tap into an external labour force. Either way, they have the means to ensure that tradesmen are not being paid for downtime. This efficient industrial infrastructure was not, of course, available to the mediaeval contractor. It is perfectly plausible that a mason-contractor or a deputy was spending time riding around to towns and villages trying to secure the services of craftsmen at the right time. Yet when we look at the decorative work of the Mooning Men Group we are seeing only the tail-end of the project. The walls and windows, timber roof beams and leaded sheets are there, of course, but we cannot apportion any of that to any craftsman or group of craftsmen. The identification of the group is evidenced by the work of what we might call “finishing teams” who left us sculptural styles and trademarks. We can identify mason-sculptor A or gargoyle carver B but we cannot identify Rough Mason A or Glazier B. Indeed, it is such difficulties that have led commentators since time immemorial to clutch at straws such as chasing after recurring masons’ marks. Once you accept that there is a group of masons at work here - and if you don’t I suggest you are wasting your time reading any further - you begin to understand how a contractor-mason might have managed all this. If your plumber was working on the roof at Lowesby and not finishing until after most of the masons had moved on to begin work at Tilton-on-the-Hill, he could arrive at Tilton just when he was needed. Ditto the other non-mason craftsman. The group made use of its resource efficiently because it was not working on one-off projects. Of course, not all the masons could move on immediately because there was work to do on decorating the cornice, installing the parapets and so on. It would be silly to speculate about how precisely they managed all this but the general modus operandi seems eminently plausible. It seems likely that the mason-contractor was likely to have had an eye to the next job at all times and to have tried to keep his core team together. Such a model would also explain why the sculpted friezes were not by the same man all the time. Sometimes a given sculptor might not be available or might have been needed elsewhere. We have seen seen several architectural elements coming together here and we have discussed the strong motivation that churches had for expansion only thirty or forty years after the horrendous series of Plagues in the 1340s to the 1360s. We need, however, to discuss other social elements that led to the commercial opportunity that the Mooning men masons were able to exploit. One of the most important was the shift in responsibility for church building and maintenance from the local grandees to men and women of the parishes. It would be absurd to suggest that the wealth of England suddenly shifted from the landowning gentry to the proletariat. The downfall of feudalism, however, must have sapped the confidence of the old order. They no longer owned the parishioners as they had before the Plague. They had to make their remaining lands pay without the benefit of enforced labour and many chose not to bother, preferring to let their land for cash rents rather than trying to turn a profit themselves. In these circumstances the manorial lord was no longer the centre of gravity for the whole village; at least to nowhere near the extent that had previously pertained. Gradually the parishioners started to manage their own affairs and not the least of their new responsibilities was the management of the parish churches through churchwardens appointed by the community. It is striking when viewing the surviving contracts for church building after the Plague that those contracting for the parish were the prosperous parishioners. |

|

Recommended Next Section: Mapping the Sculptors |

|||

|

Church Building in the Post-Plague Era (you are here!) |

|||