|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

along with the arm rest carvings, perhaps the highlight of the church. We see not just a woodwose - being savaged by a wolf - but a superb St Edmund complete with very mediaeval-looking archers, half a millennium after their Viking predecessors who perforated the sanctified King. Trigger warning: there is a wonderful (sorry - disgraceful) carving of a boy having his butt smacked by what is presumably his mother. I imagine he deserved it. Benches in the nave have other arm rest carvings, a form of decoration that abounds around here in mid-Suffolk. Finally, we have a lot of fragments of mediaeval glass to enjoy. Norton Church is a lovely place to visit in a very attractive setting and there are riches to be seen in many of the adjacent village churches west of Bury St Edmunds. See, for example, Ixworth Thorpe. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the east. This is a bright church due to the mainly clear glass. The east window was described by Pevsner as Decorated/Perpendicular transitional which is interesting. I see what he means but it is probably more a case of a mason just coming up with his own design. To left and right the west windows of the aisles are very much Perpendicular. The tall chancel arch and the lack of any traces of a rood screen speak of considerable post-Reformation remodelling. Right: The view to the west. The tower is thought to be late thirteenth century at its base, with further stages added after a legacy of 1442. Note, however, the exposed masonry courses either side of the lofty tower arch and reaching almost to roof height. These surely were the quoins of original west wall, implying that both aisles were built later than the tower. It is known that the arcades were remodelled a century later. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ten Pictures Above: The armrest carvings are fairly typical of Suffolk in general and of this area in particular. There has been some casual, but not systematic, mutilation. Surprisingly, a figure of a priest with his rosary survives. The horse (centre row) is perhaps the best-carved. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The font. It is quite splendid, incorporating three levels of decoration. The vignettes around the bowl represent religious themes. At the bottom we have four sides that are simply decorated with “window” designs representing the tracery styles of the day. Interestingly, the mason has scorned the easy option of making all four panels the same. At he corners are the best bits for we pursuers of mediaeval pagan symbols and you can see in this picture the best of the lot: a good old Suffolk wodewose - or wild man - complete with his mandatory club. The intermediate sections have angels with Marian hearts. Right: All the corner figures bear a shield. This one also has a ball at his feet. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: St John in his guise as an eagle. Below him is a very peculiar goat-like figure. Centre: The Wodewose. Right: I think this is a lion, but who knows? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: St Luke as a winged bull. Centre: St Mark as a winged lion. Right: St Matthew as an angel. All the Evangelists bear strips of parchment representing their gospels, |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Once you get past the evangelists and (below) the dove of peace, the other three panels are distinctly peculiar! Left: A two-headed eagle. This is an icon with long history. It was the symbol of the Byzantine Empire and of the Hanseatic League. Although the latter might not be totally anachronistic - a misericord at Boston in Lincolnshire is probably an example of its symbolism - little Norton is a very long way from the sea! Centre: A pelican in her piety. This is one of the most ubiquitous Christian symbols in our churches but it is far more usually carved in wood. No misericord range is complete without one, not least at Norton itself as we shall see. Sculpted ones are much more unusual and I can’t recall another example on a font, Interestingly, though, the pelican is very much the favoured wooden device at the top of the elaborate font covers sometimes seen in the east of the country - see, for example, Ufford. Right: Another peculiar choice for a font - a particularly gentle-looking unicorn! Again, we would expect to see this more commonly carved on a poppy head or armrest. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The dove of peace. Centre and Right: Amongst a galaxy of imagery at the church, this misericord armrest carving is surely the most entertaining. We presume it is the boy’s mother who is attempting to tan his hide! If you look carefully in the centre picture you can see the boy’s own hand is on his buttock. Surprised? Well., from what I can see, he is trying to protect his backside while his mother strives to remove it so she can land lustier blows! Older readers - and very definitely myself - will be able to relive painful memories here! Her other hand (right) seems to be pulling up his clothing so as to bare his butt! Way to go, mum! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The carpenter took his time over the bum-smacking armrest and I think he deserves for me to show the face of the little scallywag. Centre and Right: On the northern “range” is another fine carving of a woman carding wool.. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Six Misericords. Right in Descending Order: 1. St Andrew, to whom the church is dedicated, with his saltire cross. 2. St Edmund being martyred by very English-looking archers. 3. The inevitable Pelican in her Piety. 4. A badly defaced scene. According to G.L.Remnant it is probably pigs eating acorns from under a tree. Left Upper: Two greyhounds, one damaged. Left Below: A real treasure: a lion eating a wodewose. Close-ups and more notes on these images can be seen below. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

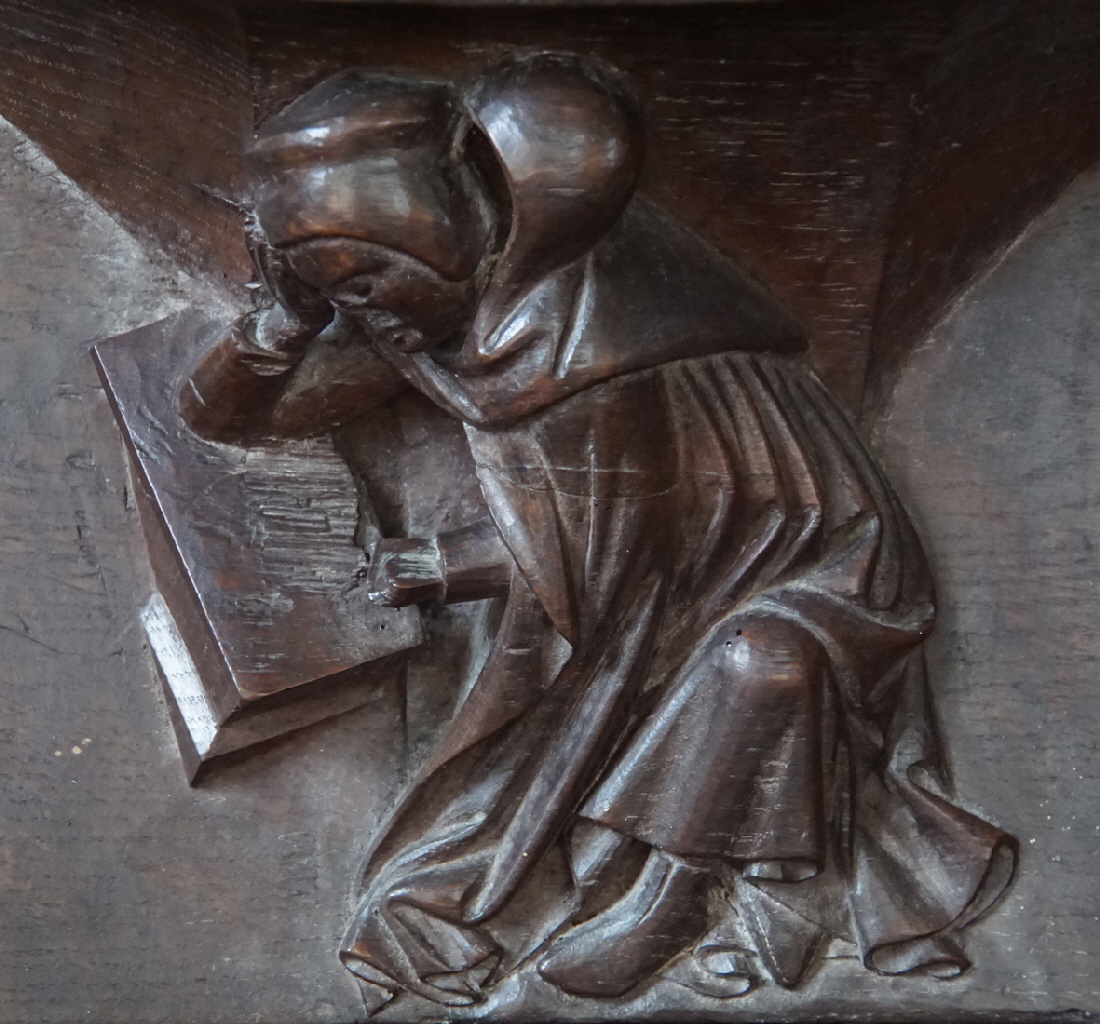

Left: A monk reading a book. Right: A woman carding wool. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The only two misericords on the north side - The Monk and St Edmund. Right: A range of three on the south side: St Andrew, The Pelican and The Wool Carder. As always in parish churches, we have to ask why these misericords were here, this never having been a monastic or collegiate church where you might expect to find them. Nor is it a rich parish church such as Boston or Nantwich where the misericords probably allowed the mercantile benefactors to intrude into the chancel area. Simon Knott on his extraordinary Suffolk Churches website mentions equally unexplained misericords at Stowlangtoft only two miles away (I have not managed to gain access at the time of writing) and wonders if they two sets are from the same site but like myself sees a lot of dissimilarities. Not least, in my view, is that the supporters (the carvings to left and right of vignettes) at Stowlangtoft are much more ambitious apart from the lovely ones on the St Edmund misericord here. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: An armrest carving. Second Left and Second Right: Two sets of arms of the Bardwell family who held the manor here (with thanks to Simon Knott for this information). Right: A censing angel. It clearly has been moved form elsewhere in the church. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

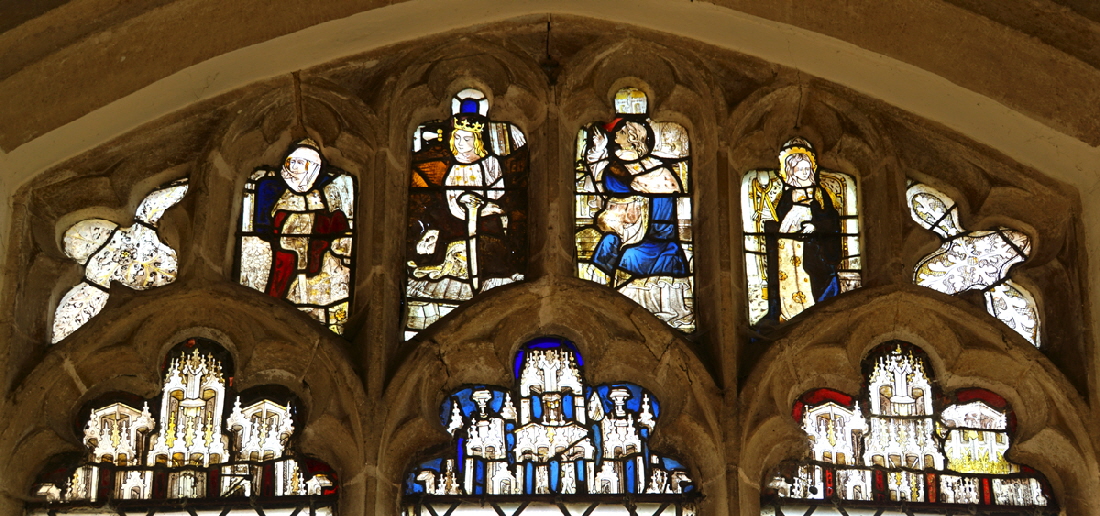

Another precious stained glass survival in the chancel. Five saints inhabit the top lights. One image is completely unidentifiable due to an obliterated face. The Left hand figure is surely St Edmund as he wears a crown and a nimb. A very fine St Christopher (second left) is clearly identifiable. He was venerated everywhere, especially in his native Suffolk. Third Left: This figure holds a martyr’s palm but I cant identify who it is. Normally the saint would bear a symbol of the method of execution (eg St Catherine’s wheel) but I cant see one on this image. Third Right: Unidentifiable. Second Right: Seems to have been restored - and who is most likely to be St Etheldreda (AD636-77) . Also known as Aethelfryth, she was daughter of King Anna of East Anglia. She married a Prince Tondberct upon the condition she was allowed to remain a virgin! He died of frustration in AD665 and Etheldreda, by then in a nunnery, was married off again to Ecgfrith of Northumbria, a much more well-known figure and then only fourteen or fifteen years old. In AD672 he asked the renowned Wilfrid, Bishop of Hexham (yes, he was made a saint too), to restore his marital rights. Etheldreda managed to escape his would-be lustful clutches and washed up at Ely, in which inhospitable Fenland location, she and her chastity were safe. Far right is St Andrew with his saltire cross. The designs at the bottom of the tracery are reconstructed but show good representations of the architecture of the day, |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

More mediaeval glass. This time the main figures too have been reconstructed from fragments. If you look closely you will see, for example, that the woman’s wimpled head in the panel second left has ermine at her neck. That surely belong to the King next to her. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Two close-up examples of mediaeval tracery glass. You can see that they show high Gothic architectural forms with lots of pinnacles and crockets in evidence. |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

These shields are just four of a number carved on a roof dated 1897. They are an odd lots and at first I thought the carpenters were showing their own tools but I soon realised this could not be the case. Left: The saw is the symbol of St James the Less. One of the legends of his death (typically gruesome) was that the was condemned by the Jewish Sanhedrin who had him thrown from the Temple, stoned to death and sawn in half. Don’t you just love the saw portrayed here straight from the Victorian carpenter’s toolbox? They caused some confusion, did the Jameses. St James the Great has a scallop symbol (also in this series at Norton) and was also, of course, a disciple and brother of St John. Jesus also had a brother named James. Second Left: Probably St Simon the Zealot. This is, I think, a falchion or short sword used in his martyrdom, seen here as a scimitar! Second Right: This will be St Matthias, the “thirteenth” disciple who came off the substitutes bench when Judas Iscariot was shown a red card for a bad foul. He was also stoned before being beheaded by an axe or halberd. Far Right: The money bag is a symbol of St Matthew (the disciple, not the evangelist) who was a tax gatherer. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Painted mediaeval woodwork in the east end of the chancel. Right: The north side. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The priest’s door with holy water stoup. Centre: An iron knocker - possibly a sanctuary knocker? Right: A macabre gravestone. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The church from the south. Note the Perpendicular style windows that are particularly fine here. So often such windows were installed almost at random in mediaeval churches over the centuries in a haphazard and architecturally unsympathetic way but here at Norton they have created a harmonious look. Note the unusual east window in the top of the nave. Right: The church from the west |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Misericord Close-Ups |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A Wodewose being savaged by a lion. The carpenter has done a creditable job of representing a lion, with his quite realistic mane and cat-like physique. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

St Edmund with his customary crown and beard in ringlets. Three of his limbs have been lost. Very mediaeval-looking archers prepare to use him for target practice. The carpenter will have had no idea what a Viking looked like, of course. The degree of damage suggests carelessness or vandalism rather than iconoclasm, St Edmund having not been defaced. The large oak leaves are a curious embellishment. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The supporters on the St Edmund misericord. Again, they have mediaeval costumes. Damage to these relatively innocuous figures suggests that the damage to the misericords is the result of careless handling rather than of iconoclastic vandalism. This perhaps reinforces the notion that these misericords were moved here from elsewhere. If, as seems almost certain, that site was a priory then their treatment by Thomas Cromwell’s men was unlikely to have been gentle. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Supposedly a monk reading a book. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

St Andrew with his saltire cross. Although the men around him look as if they are engaged in securing him to the cross. There has clearly been deliberate defacement of the figures here. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

We have to assume that this is the Pelican in her Piety, although the pelican looks more like a rather impressive eagle. Note the unfortunate and very long animal that is being crushed under the weight of the whole thing! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Two greyhounds, the front one badly damaged. Again, we cannot pin this damage to the notion of iconoclasm but perhaps we should not be surprised if the people employed to do such work were not great intellectuals and simply took their axes to everything to be on the safe side. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The woman carding wool. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||