|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Introduction

This piece of writing was loaded to my site in June 2020, just as the Covid-19 lockdown in the UK was being eased. It amends and expands an already-weighty article that was on my site for some years. Given its timing you can be forgiven for thinking it was a “lockdown project”. In fact it was not. As always I have hundreds more churches I would like to write about but lengthy correspondence with a friend who is a Freemason - and who would probably not endorse some of my key points here - and some new reading provoked me finally into this lengthy update. Having said that this was not a lockdown project it is a considerable irony that much of what I have to say here reflects changes in the society, employment and in the church building environment in the two hundred years following the Great Plague of 1348. That Plague which killed anything from 40-60% of the populations of most European countries was a catastrophe on a scale that is unimaginable to us now. Imagine the breakdowns we would suffer in our modern civilisation if we encountered a disease with a death rate of 10% never mind 50%.

One could write a considerable tome about what is not known about mediaeval stonemasons! What we have is a meagre patchwork of evidence that provides a foundation upon which no self-respecting stonemason would build a wall, let alone a church. From this many authors and writers have made sterling attempts to get to the bottom of what was really happening in the mediaeval building industry. There is much amicable disagreement. This article is my own attempt to precis those books and papers to try to arrive at a view that some would dispute but which is, I think, at least coherent. Like all articles on the subject I have to use intuition, inference and a large dollop of assumption. Almost all the “facts” are second hand: there is no original research here.

I have, however, to declare an interest. My work on my book “Demon Carvers and Mooning Men” is what instigated my need to understand how a group of men came to be altering and adorning several parish churches in the East Midlands in the early fifteenth century. That work led me to suspect that the industry was much more “industrialised” than many suppose and I believe it gives an insight as to what was really going on at that time and that it is a valuable insight into the whole subject. Unfortunately, such is the scantiness of available evidence that confirmation bias is hard to avoid - but I have done my best!

|

|

|

|

Why should we church visitors care? Well, every church on this website owes its birth and development to the skills of stonemasons and if you admire their work then you should surely have some interest in the men themselves. Their work is ubiquitous. No single trade has left such an indelible mark on our landscape. Yet so little is known of the masons - who they were, what motivated them, how they lived their lives, how they acquired their skills. There are, as a matter of fact, quite a few books commercially available. I own most of them. They all suffer from the same inescapable shortcoming: they focus almost exclusively on the masons employed in the building of the cathedrals and great abbeys. They studiously avoid the subject of the humble parish mason for the simple reason that they know nothing about them! Whereas cathedrals and abbeys were managed by literate administrators who left records, the parish churches left hradly any records at all. Most “coffee table” books regurgitate the same old same old accompanied by the usual lashings of reproductions om mediaeval illustrations.

Sadly, by evading the topic completely they imply that the two groups of masons were of a kind. In terms of the challenges they might face and the skills they required that is largely true. That is largely where the similarities end. Think of a "white van driver" and then think of a Grand Prix racing driver. They have skills in common. Perhaps both think time is money! Both can drive a car. But then think of the differences in motivation, skills and what they are paid. That seems to me to be a good parallel when comparing the cathedral stonemason and the parish church stonemason.

|

|

|

|

Guilds, Masters, Apprentices and All That

The traditional view of the stonemasonry industry as peddled in those coffee table books I have referred to goes something like this. Master masons built churches. They were all geniuses. All stonemasons, like any other craftsmen belonged to a guild. An entrant to the trade would be legally bound to a master for seven years as an apprentice during which time he would receive board and lodging and paid a pittance. After seven years he would be “examined” by the guild and if all was well would be pronounced a “journeyman” mason. After yet more training he might aspire to become a master himself and would submit to further examination and would have had to produce a “masterpiece” for the inspection of the guild. The masons were governed by the guild which would insist upon proper professional standards and straight dealing. Signs and passwords would be revealed to him by which, in the absence of certificates or diplomas, the mason could prove his status to other masons. “Secrets” - erudite insights into building - would be revealed to him as he progressed through the hierarchy.

This is more or less what I was taught about the mediaeval craft industries about a century ago in primary school. So when those coffee table books and other besides trotted some of all of this I believed it. In fact it is probably more or less true for most trades and crafts in mediaeval England. Let’s call this the “Freemasonry” school of thought because this is more or less what the modern movement holds to be true. It is a vision of an industry that was structured and disciplined and inherently moral.

Not only is that probably true of most English crafts but it seems to be true, at least to some extent, for the stonemasonry industry in some other European countries - particularly some of the states that now (but didn’t then) form part of Germany.

A polar opposite view of the Freemasonry School of Thought would say that here were no guilds, no industrial structures, that all masons rubbed along as best they could, getting their training on the job, working where they could until they reached a point where they could become a guv’nor, employ other masons and become building contractors. Call this the Free Market School of Thought.

As we shall see, the Freemasonry School of Thought is undermined by a heavy weight of circumstantial evidence. It cannot be disproved because nobody can prove a negative hundreds of years on, especially when documentation is so sparse. The Free Market School also does not stand up to much examination. We know that there were men called master masons and The “truth” must lie somewhere between those two extremes. But where? Don’t expect some blinding revelation about how the industry. The answer is messy.

|

|

|

|

Who Were They?

There are about eight thousand pre-Reformation parish churches in England. We don’t know how many have since disappeared but it is probably a lot higher than we would think in an age where historic building are “protected”. Let’s hazard that the average church was built saw three major phases of construction. Let’s assume that the average number of masons (not labourers) for each of these phases was a conservative twelve. That suggests that more than three hundred thousand masons worked on those churches. Some, of course, will have worked on more than one church but equally there was much church work going on in between phases. Let’s use a very conservative round number of a quarter of a million. I’m not sure anyone has ever counted how many parish church masons have been actually mentioned in surviving documents. I am going to guess, based on the documents I have read, that it is no more than five hundred. These numbers are, I am sure, miles out but however you look at it the quarter of a million or a million, whatever, is almost totally anonymous. Today, if you have that good old English surname "Mason" then you will know there was a stonemason somewhere in your family tree. The man would have had his "given" name - let's say Roger. To distinguish him from other men with the same name in a village he might have been called “Roger Mason”. When he worked on a building site where there were lots of Roger Masons and William Masons, he might well have become “Roger Ashby” or (real example) “William Helpston” reflecting where he lived. Remember, then when you read further that masons did not carry paperwork and passports. There were no censuses. A man’s baptismal name might be the only one that was constant as he moved from site to site. This if course underpins the Freemasonry view that trained masons must be able to identify themselves via signs or passwords.

|

|

|

|

Left: This roof boss at Canterbury Cathedral is believed to be the face of Henry Yevele (c.1320-1400). Probably England’s greatest and certainly most famous stonemason, he worked on Westminster Abbey, Windsor Castle, Canterbury Cathedral and numerous castles. Right: Possibly, “Ralf of Ryhall” stonemason at Ryhall Church, Rutland and others in the area, early fifteenth century.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Stonemasons Guild

The existence of a network of a whole network of stonemasons guilds is the cornerstone of the Freemasonry School of Thought as discussed earlier. If they did not exist then all notions of industrial governance, apprenticeships, masterpieces, hierarchies, signs and passwords, “secrets” are thrown into doubt. There is documentary evidence of some guilds. That London had one is beyond dispute. But outside London the evidence for stonemasons guilds is worse than patchy. In fact it is near to non-existent.

In 1933 two Professors from the University of Sheffield - Douglas Knoop and GP Jones - produced a work called "The Mediaeval Mason”. Their work can still be found on the internet with a bit of persistence and it is still referred to by most writers on the subject. Amongst their many startling conclusions, Knoop and Jones, found that it was unlikely that a stonemasons guild existed in England outside London until the sixteenth century. Of course, proving a negative is well-nigh impossible but the men cited these three principal reasons :

1. Guilds were local town-based institutions – they were not national organisations - that governed the trades within their towns. Masons were freemen as opposed to serfs. Studying the freemen rolls that still exist, they noticed the startling absence of masons. That, they felt was hardly surprising: the fact was that homes in mediaeval England were not made of stone. The only stone structures in a mediaeval town were likely to be the church and maybe a bridge. Masons could not make a living in a town. They had to follow the work and that legislated against belonging to, let alone being governed by, a town-based guild.

2. The few extant records of payments to masons show great inconsistency in rates. Guilds, amongst their many other activities, standardised rates of pay in order to protect their members and ensured a maintenance of professional standards so that their crafts were not brought into disrepute.

3. A great many masons were employed on royal projects, either voluntarily or by impressment (of which more later) that could not possibly be governed by guild rules. The same is true for the great cathedrals and abbeys who probably had groups of masons employed directly on a semi-permanent basis.

London was, as usual in these things, a “special case”. Of the cities, towns and villages of England, only London had need for a permanent local masonic workforce. There is evidence that there was some sort of organisation in 1306 when threats were made against newcomers to the City should they accept wages lower than those of the local craftsmen - a familar trade union-style preoccupation. In 1356 the famous Master Mason, Henry Yevelle (“of Yeovil”), helped to draw up the regulations for London's stonemasons but there is no mention of the existence of a London guild.

On the face of it, 1356 was a bad time to be laying down articles and rules for a labour organisation. The Great Plague of 1348-50 had annihilated up to half of the population, masons included. Those remaining should, from our modern perspective, have had the whip hand in wage negotiations and it is clear that even in mediaeval England the laws of supply and demand could not be altogether eliminated. Wages started to rise and King Edward III - whose main preoccupation was slaughtering Frenchmen - and his sidekicks did not much care for that. So as early as 1351 the King invoked a “Statute of Labourers” to control wages. As we can readily understand, Edward would have perceived the guilds as a potential force of resistance in much the way modern British governments has sometimes viewed modern trade unions.

The 1356 “regulations” drawn up in London was almost certainly an attempt to counter Edward’s baleful views by emphasising their good governance. The rules were not only commercial but laid out standards of personal morality and good faith. Yevelle’s involvement was surely intended to provide credibility at a time when the craft felt under siege.

After the Peasants Revolt in 1381 Richard II - one of England’s worst kings in the face of stiff competition - passed an ordinance that all Gild warrants were to be laid before him. In 1425 all annual assemblies of gilds were banned by Henry VI. The “persecution” of the guilds continued intermittently for almost the remainder of the mediaeval period. It is against this background that many of the churches mentioned on this website were being built or, much more frequently, being extended and updated.

Knoop and Jones were unable to discover a single example of guild regulations preserved in England. The “York Memorandum Book” preserves the gild regulations of forty gilds but none for the stonemasons. The same was true for Norwich, Leicester, Bristol, Coventry and Nottingham. Guilds as we think of them almost certainly did not exist in the stonemasonry industry. Later I will be discussing the records of building contracts made by the colleges of Oxford University. The author thought it worth making the point that in this - one of the most comprehensive set of documents relating to mediaeval building - there was not a single mention of a stonemasons guild.

And yet, there are indications of stonemasons outside London! Famously, William Horwood who contracted to build the nave at Fotheringhay, Northamptonshire signed himself “Master of Stamford Guild”. As we shall see, this might have been a somewhat hubristic self-designation but clearly something existed in Stamford. The list of guilds taking part in the Corpus Christi Mystery Plays* at Norwich in 1449 also lists the masons. You might feel, as I do, that this is little enough but it proves conclusively that provincial stonemasons guilds did exist, even to a limited extent.

Yet, given the relative ubiquity of works of masonry associated with the English parish church it seems likely that the masonry craft was, as Knoop and Jones infer, governed very lightly if at all in many provincial areas. That presents us with problems in understanding the masons. If the industry was not much regulated (at least outside London) then how can we begin to understand the concepts of Master Mason and apprentices?

We need some context here perhaps. There is no doubt at all that the guild system as a whole was under attack from the mid fourteenth century until at least the seventeenth century. We should not be too surprised. More or less absolute rulers are rarely fans of self-governing organisations. In more modern times trade unions have been more or less mired in controversy and conflict with authority – think of the Combinations Acts, the Tolpuddle Martyrs, the General Strike and the Winter of Discontent as just a few manifestations - creating a narrative that still partly defines the English Labour Party today.

It is surely incontrovertible that a guild for stonemasons would struggle with the special challenge of a peripatetic workforce? Add to that the problem that the largest projects – castles, abbeys, cathedrals, great houses – were carried out for the most powerful patrons in the land who were unlikely to be dictated to by organised labour. I would be interested to see a single recorded instance of mediaeval masons downing tools at such a site! That brings us onto another point of difference: that the masons worked often in gangs and not as individual craftsmen. All of this might suggest that official antipathy to any stonemasons guild might be stronger than for other trades.

All of this points to the certainty that any stonemasons guild was unlikely to have much in common with the municipal craft guild where work was likely to be on a “per job” basis and involve individuals rather than teams or gangs. We know there was a London guild. We know there was one in Stamford in the fifteenth century and there are snippets that suggest occasional establishments in other provincial towns.

So if we suppose that stonemasons guilds existed at all then what form did they take? Well let us imagine the Stamford guild. What better place for one? Stamford was then an important town and one with fourteen parish churches, a castle, town walls and a bridge. If there were masonic guilds then you would expect Stamford to have one. Yet this guild was known to exist in 1438. That is, right in the middle of the series of acts designed to control wages. The next set of statutes was to be less than ten years later.

We know William Horwood was its “master” – see “The Fotheringhay Contract”. We can see from that contract that Horwood was designated only as a “freemason” in that contract and that the House of York who engaged him treated him with something approaching disdain, even foisting some masons of their own choosing upon him and threatening him with prison if he finished the work late. That does not imply much respect for the man or his supposed position. Given the series of sanctions against the guild movement by respective kings, why should they? In fact the craft – as opposed to its famous exponents – was mistreated pretty well until 1666 when Charles II needed masons to rebuild London after the Great Fire.

The safest conclusion to draw, in my view, is that such stonemasons guilds as existed were spread very patchily and may have had little longevity. Moreover, having seen that they had little control over wages and that their “membership” was likely to be peripatetic it probably had very limited practical value at all. It could well be that they were largely ceremonial and that is how they managed to avoid sanction. It seems inconceivable that they could carry out functions that would have been be regarded as illegal. These were not, after all, secret societies, as we know from William Horwood’s hubristic designation of himself as “Master of Stamford Guild”.

* The mystery plays were a feature of life in many English towns. They were performed back-to-back by the municipal guilds, each play having a religious theme. Why were they called “mystery plays”? “Mystery” in this context is possibly meant in the sense of “miracle”. However, it is also suggested that the word is a corruption of “ministerium” meaning “craft”. To this day, Freemasonry talks of itself as being a “mystery”.

|

|

|

|

The Lodge

In the absence of a guild, the institution that was important in the world of the stonemasons was the "Lodge". You will probably be familiar with this expression that defines the local meeting places of modern Freemasonry - of which more anon. Suffice to say at this stage that there was no connection between the lodge and Freemasonry in the mediaeval period. The word “freemason” had a much more functional and less romantic connotation.

The Lodge was a physical place on a building site in mediaeval times. One side would have been open to the elements and the lodge might have abutted one of the walls of the building. This Lodge would be the nerve centre of the operation and used for meeting, eating, planning and perhaps for fine carving work.

That physical building, also had a less obvious significance. When a Master Mason moved on he took his lodge with him. By that we don't mean the physical building but the organisation and culture of the Master Mason and those who worked with him. For a Master Mason continuity amongst his workforce would be a big advantage and it is safe to assume that he would be looking for his next job before that in hand was finished. Similarly, we might surmise that Master Masons were not averse to "tapping up" men on nearby sites where the Masters had not yet secured the next job.

This is mainly informed surmise because, unless I've missed it, nobody has studied or speculated what the working life of a mason might have looked like, as opposed to a single project; but my studies into the East Midlands School of Church Carvers were instructive in this regards. Firstly by identifying their very distinctive external carvings we can be confident that in this area at least there was a group of men, probably of shifting membership, that went from church to church in the early fifteenth century extending aisles and raising clerestories. I identified five distinct carvers.

Some of those churches were extremely close together: the distance between Lowesby and Tilton-on-the-Hill in Leicestershire, for example, would be an unchallenging country walk. It is obvious that the same men worked on the two sites and inconceivable that the work was not consecutive or even, just possibly, concurrent.

Even the carving of sub-parapet friezes at all - a very localised phenomenon - suggests a building culture at work amongst the masons, and very certainly amongst one or more Master Masons. Beyond that, however, and most telling of all, is the plethora of "trademark carvings"- notably the mooning man - that are surely products of what we would today call a corporate identity. That identity was surely forged in the closed world of the Lodge.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Recruitment and the Masonic Hierarchy

Knoop and Jones found no references in any records to "journeymen" and hardly any to "apprentices". This reinforces the notion of a guild-less trade, or at least one where the guild system operated in a less prescriptive fashion.. So what was the masonic hierarchy?

At the top of the tree, it hardly needs stating, was the Master Mason. He was a very big cheese indeed and would command the whole workforce, not just the stonemasons. On big projects he might have a Clerk of Works. Below him were masons of the ordinary sort. Straight away we are into problems.

In general the everyday masons were divided between the "hewers" (or "cementarii") and the layers (or "cubitores"). The hewers shaped the stone and the layers set it in place. Hewers were paid around 20% more than layers. So far so good.

In many accounts, however, other terminology emerges. A “scappler” (or batrarii), for example, seems to have been a hewer of a somewhat more humble sort. They would use cruder tools – generally hammers and axes – to roughly shape the stones for their more skilled brethren to work upon. Unsurprisingly scapplers (isn’t that wonderfully onomatopoeic word?) were common in the quarries.

Then the terminology starts to change. The words “roughmason” and “freemason” start to make an appearance and by the time of the Oxford Contracts we will be looking at later, these. have become the dominant descriptions and it is widely believed that they are synonymous with respectively layers and hewers. “Freemason” is such a loaded word I shall discuss it separately. Then we get pavers (“pavours”), wallers (“muratorii”) and image makers (“imaginatores”) to name but a few variations. What is very clear is that these terms often refer to the work that a man was performing on the site; not to some “grade” or position in a masonic hierarchy. Indeed, one might argue that the chaotic hierarchy is another argument against the widespread existence of stonemasons guilds.

Then there were some very few apprentices. In fact references to them in contemporary documents are startlingly scarce. Only one apprentice is mentioned amongst the four hundred and fifty masons mentioned in the Oxford College records. This scarcity tells you also that they must have been apprenticed to master masons, not to jobbing masons. An apprentice was owed board and lodging. How would an ordinary mason be able to provide this in a craft that was by its very nature peripatetic? How could the ordinary mason afford it anyway? A journeyman tailor, for example, would have his own premises and his own customers and could make payments to an apprentice from his own income. An ordinary mason had no customers of his own. He was paid on a daily basis by the Master Mason or those that commissioned the building project. Patrons had no interest in paying for trainees so on those rare occasions when they appear in accounts it must demonstrate that the apprentices could already blow their own noses in terms of contributing to the building project.

It seems likely that the trade was very much a family affair. The Master Mason would probably employ his sons or nephews as soon as they were old enough to handle a hammer and chisel. The ordinary mason might likewise try to teach his own sons and nephews the basics as part of their upbringing in the hope they could find work as a hewer or layer, jobs that were much better paid than labouring on the land or at the building site. It is a prosaic proposition but there is no evidence for anything more sophisticated than that a boy learned on the job.

Finally, another source of labour was the quarries. Quarrymen would understand the vagaries of stone and would understand how to cut it. It is a reasonable inference, in fact, that the quarry was the principal training establishment for would-be masons. There a boy might learn the rudiments of hewing before finding employment as a roughmason where he might learn more advanced skills of hewing. I emphasise that this is speculation on my part. Knoop and Jones found that the same man would sometimes appear on the payroll of the local quarry and then on that of a cathedral or castle. The same could happen in reverse. A stonemason, however skilled, would sometimes have to take work where he could get it. This would be particularly so after the great plagues of the fourteenth century. From then on, shortages of masons led to a significant outsourcing of work to the quarry. The Perpendicular style of architecture was significantly less flamboyant in parish churches and the making of, for example, window tracery in the quarries was no longer unthinkable.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Master Mason

The published literature is prone to waxing lyrical at the near-mystical status of the Master Mason. By which, of course, they are referencing the cathedral and abbey builders again! It’s a good excuse to produce a nice coffee table book with colourful reproductions of illustrations from mediaeval manuscripts and those wonderful photographs that make you gasp at the “genius” of it all.

Those establishments would have a resident Master who would not only be very well-paid but would also be given living accommodation, robes and so on. Such a man might well have renown and find employment on prestigious projects across Europe. Many an English abbey or cathedral knows the name of its principal masons. So far, so easy.

That, indeed, is where “easy” more or less ends. If you accept that English stonemasons guilds hardly existed then how could the traditional routes to master-ship as we understand them in other crafts be sustained? We must, in fact, go even further. To what extent did the title of “master mason” exist at all as anything more than an earned title as opposed to one gained by examination? What institution existed for their examination – and here, again, we have to allow London as a likely exception.

That “master masons” existed as a concept and as a title is indisputable. The Oxford College records referenced elsewhere record the names of over twenty. Although there are few surviving contracts for parish church construction, detailed accounts for royal and public projects do exist and master masons are mentioned frequently. So we have master masons and possibly few or no functional guilds and that is a challenge for us to understand. We would instinctively have expected a master of any craft to have completed seven years of training before attaining the status of what other trades (but not the English stonemasons) called “journeyman” – men paid by the day. Then he might do two or more years of training before producing his “masterpiece” (easily understood within the context of, for example, goldsmiths), being “examined” by master of his guild and then if he was fortunate being designated “master” of his craft.

Let us, however, draw a distinction between a master mason and, say, a master goldsmith. The worst consequences for a botched job in most trades – even perhaps in other building trades such as carpentry – would be a lot of wasted work and materials, a disappointed client and a ruined reputation. For a stonemason it could be a large collapsed building, the waste of thousands of man hours of labour or a lasting monument to his incompetence. This was a trade in which working beyond the limits of your competence could have catastrophic consequences – as the innumerable accounts of collapsed church towers amply attest.

Are we to believe that the retained Master Mason of, say, York Minster was of equal competence and standing as the man who extended the aisles at almost any given parish church in England? Of course not. To obtain a job such as at York a man would need to build his reputation by success in projects of gradually increasing complexity and size. Just, in fact, as would happen with a modern architect.

We can go further. Even when considering the parish church extension – surely one of the staples of the masons trade especially post-Plague – the contracting mason (“master” or otherwise) would have had to have procured and managed a fair-sized workforce including masters and members of other crafts, perhaps to have procured materials, to have designed the work and possibly to have managed the project from end to end. It is not a stretch of the imagination to suppose that many designated “masters” never had the competence, confidence (or capital) to undertake such a project. Even if an organised stonemasonry guild had existed, how were the established masters to ascertain competence in such fields? We can only conclude that once the status of master had been achieved – by whatever means – that was only the start of the story.

Then we have to consider the reverse of this situation. If we accept that a contracting mason needed many of what we would today think of as skills in procurement, man management and project management as well as probably an access to capital, how important would the level of his manual skills as a mason be? It would, of course, depend upon the project but we have to consider that, to simplify things, evidence of his ability to manage a project to completion to a competent standard within a timescale and to a budget was likely to be more important to many clients than how prettily the mason could carve a gargoyle! For other clients, those with money and who sought prestige in the finished work, imagination, design skills and knowledge of the latest developments in architecture would have been paramount and worth paying top dollar for.

So we can safely say that a “master” was not necessarily a “Master”. This is not to denigrate the role. Even the most basic building work was not a “walk in the park” and we can be sure that the path to such a position was a long demanding one and that the title had to be earned. It is just that it is not clear how it was conferred. LF Salzman in his seminal “Building in England down to 1540” was of the view that master masons might well have been constrained to take work as a common mason where economic circumstances demanded it. When we look at the “Oxford Masons” in a later article we will see evidence of that.

A question I have never seen addressed is how many master masons were there in England at any one time? How did their numbers compare with masons of the more ordinary sort? What was the scarcity value of the master mason? How much wage premium could he command? Startlingly, the Statute of Labourers of 1353 laid down a maximum wage* for common masons as 3d per day. For those designated “Master Freestone Mason” the maximum was 4d, a premium of only 33%. The 1360 Statute maintained those rates although the new designation was “Chief master of masons”. The Henry VI statute of 1444-5 declared “Frankmasons” (presumably freemasons) as worth 5 ½ d, a “roughmason” 4 ½ d. There was no mention of master masons begging the question whether the expressions were at that time regarded as interchangeable. Henry VII’s 1495 statute rates both “Freemason” and “Roughmason” at 6d per day. “Master masons taking charge of work and having under them six masons” are to receive 7d.

There is a lot to contemplate here. All of the extra training to become master mason, the supposed mastery of geometry, the supposed examination by other masters, the production of a masterpiece, the supposed understanding of the supposed “secrets” of the craft were consistently rated as being worth 1d per day! By the time of Henry VII even that premium could be won only if the master supervised six other masons. In our world a span of responsibility for six people and a premium of 16% would look like a “Team Leader”, not an architectural genius and expert project manager! Furthermore, if you believe that the wage premium must roughly reflect the scarcity of the men filling the role, then you would have to conclude that there were rather a lot of master masons around. It hardly sounds like an exclusive club.

It is frequently cited that the Statutes were widely flouted. When we look at the Oxford masons we will see evidence that that was true but that there were attempts at enforcement.

We must, then, dismiss the romantic notion that all master masons were architectural and artistic wizards. That there were such men is beyond dispute but as we wonder at the nave of Wells Cathedral we must not assume the same level of skill for the man who built the aisles at Wells-next-the-Sea! Nor should we even assume that any of these wizards could pitch up and conjure a church from out of the ground. Nor should we assume that a client would take for granted that ability.

In reality, as you read the pages on this website, you will understand that most churches developed over a few centuries. Many started life as simple two or three-celled Norman affairs. To be sure, there was nothing straightforward about the construction of, say, a Norman apse but it would be a mistake to look at a mediaeval church with nave, chancel, two aisles, clerestory and west tower and suppose it was all down to the genius of a single man created to a single brilliant plan. In reality, several master masons would have contributed to this structure over a considerable time, each standing to some extent upon the shoulders of his predecessors.

I became particularly aware of this when researching the frieze carvings of the East Midlands. Time and again it seemed that the carvings had been added at a time when a church's aisles were being widened and its clerestory added. The men who carried out this work were not church builders per se: they were the equivalent of today's local building contractors who will happily provide you with an extension or loft conversion at a price!

Master Masons were not then equal except in the title they carried. Some will have been renowned and employed by the largest and best-endowed churches. Others will have taken work wherever they could find it. By the fourteenth century the number of surviving Master Masons who had ever built a church from scratch must have been vanishingly small. On the evidence of the extant church building contracts I suspect that a great many improvements and extensions to parish churches did not involve a recognised master mason at all until, possibly, the mason’s guilds with all the implied hierarchy and labour regulation became a reality in the sixteenth century. I discuss this more under “Contracts” later in this article.

Having knocked the parish church master mason off his pedestal to some extent, I must now redress the balance. The master mason needed a great array of skills. Let us consider the modern architect. He or she will take a commission from a client and then sit down to prepare some designs, sometimes of stunning impracticality. He will consult his client, showing him artist's impressions, extensive diagrams and models. He will specify what materials are needed and will produce some blueprints. Then he will hand it all over to builders and craftsmen to do the work while he hopes for an award from his industry (do I sound a bit cynical here?).

The master mason had little in the way of drawing materials and no means to produce blueprints. His clients would often have been no better educated or any more literate than himself and would probably have little knowledge of what was possible and what was not. Having reached some kind of vague agreement the master would make a contract with the client and then he would plan and manage the whole project. He would usually recruit the workforce. If the contract demanded it he would source the materials needed and arrange for their transport to the site at the appropriate time. He would communicate to his workforce what needed to be done (more of that anon) and make sure they did it. He would manage what we now call "human resources" and have the power to hire and fire. He would work to a budget. Increasingly, he will have been managing the whole project to a pre-agreed budget. He would manage his client's expectations in the face of misunderstandings, snags such as bad weather and disease, substandard materials and all the endless disputes with contractors. In short, all of the things that we know can go wrong with the building of a modern house!

*For the sake of simplicity I quote the rates pertaining from Easter to September. Rates outside that period when working days were shorter because there were generally 1d per day lower.

|

|

|

|

Freemasons

The word “freemason” does not appear, according to Knoop and Jones, until 1376. That it does so quite late in the mediaeval period might have something to do with the advance of English at the expense of Latin (and French) in the world of commerce. I am not going to paraphrase Knoop and Jones, but quote them verbatim:

“In its origin, the word “freemason” would undoubtedly seem connected with “freestone”, which is the name given to any fine-grained sandstone or limestone that can be freely worked in any direction and sawn with a toothed saw. Such stone can be undercut and lends itself therefore to the carving of leaves and flowers in relief for the purposes of decorating capitals and cornices, to the cutting of tracery and archmoulds, and to the carving of images and gargoyles. Further, it can dressed into practically any regular geometrical shape with a chisel and hammer and is consequently used for window frames, doorways and vaulting, even when no ornamentation is called for.

Thus the skilled worker in freestone would be both an artist in his capacity as carver, and a precision worker in his capacity as cutter of the very exact parts which, when assembled, produced, for example, a rose window or fan vaulting. The high class freemason had to not only to be an adept with the mallet and chisel and in the making of his own moulds or templets, but had to be an expert in the art of setting; if the carving was partly or wholly executed in the lodge before being placed in position it would obviously requite the most careful handling when being set, whilst the slightest slip or carelessness in the matter of too much or too little mortar in setting an elaborate window would destroy the symmetry, if it did not entirely spoil the work.

The skilled freemason, therefore, in many cases set his own work and would thus not only be an artistic carver and exact hewer of stone, but also an expert setter. Beneath these high class craftsmen of varying degrees of skill would be freemasons who were skilled in straight moulded work and freemasons who prepared ordinary square ashlar with a chisel. Straight moulded work and ordinary square ashlar were probably set by the layers (or roughmasons), though the freemasons were no doubt qualified to do the work.”

So we can see that the freemason was not defined by his “freedom” as many assume (all masons were equally free or otherwise) but by his ability to work in the finest stone that was used for the most decorative purposes.

Knoop & Jones imply that all freemasons were not equal and even that the lowest level of freemason might be synonymous with “hewer” in the same way as “rough mason” may be synonymous with “layer”. It does seem that the title “Freemason” was simply a reflection of a man’s abilities and that it was not a title conferred in a formal way by, for example, a guild. “Freemason” was easily the most common title for a mason undertaking building work under contract.

We will discuss “Freemasonry” as a modern institution later.

|

|

|

Planning and Communicating

Think now of a world without pencils and paper and where most of the workforce was illiterate. How was a Master Mason to plan and how was he to communicate to his men?

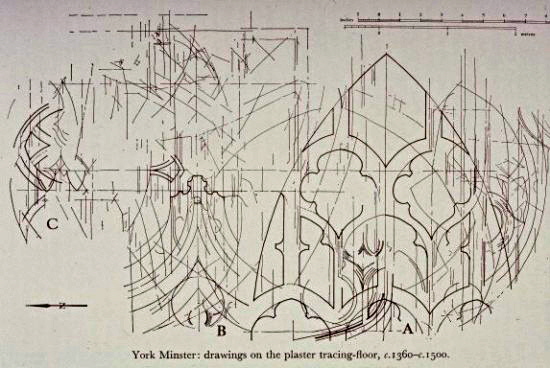

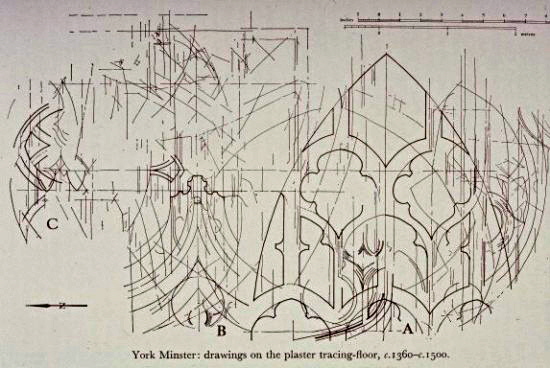

Knoop & Jones uncovered evidence that one of the first tasks of the Master was to prepare templates made of wood or sheet metal. If he needed a cross section of a pillar, for example, he would make a template for his men to copy. Similarly for window tracery. Some of these templates still exist in the roof York Minster.

There were writing and drawing available but they were scarce and expensive. Also the plans for a church would call for an impracticably large canvas. The masons, then, were wont to draw in a box filled with sand or plaster. Again, at York Minster the "drawing floor" still exists.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left: Part of the drawing floor at York Minster. The lines inscribed in the plaster are very clear. Centre: A reproduction of lines on the drawing floor at York as created by the mediaevalist John Harvey. Right: Masons templates at York. The pictures to left and right have been reproduced from work by Vicky Sypsa found on the internet. I haven’t been able to trace her for permission to re-use her pictures. I hope she will forgive me!

|

|

|

|

The Skills

Where, you might ask, did the masons get their knowledge of geometry? To put things into perspective, the Oxford Geometry set I had as a twelve-year-old had something no mediaeval stonemason had: a protractor! He had no knowledge of pi, nor of trignometry. He managed with tee-square, a ruler, a homemade device to measure verticals and horizontals and a pair of compasses. In fact, he had no notion of geometry at all as we would know it. He simply knew how practically to make things work.

In his paper "The Education of Mediaeval Master Masons" Shelby points out that even the Grammar Schools of England provided no mathematical tuition whatsoever. They were "grammar schools" in a quite literal sense. Neither did universities provide such education, even supposing a mason could ever aspire to it.

It may sound prosaic but Shelby concluded that the skills of the mason were simply learnt on the job and that its corpus of knowledge was one that the craft had garnered through oral communication over centuries. It was once fashionable to suppose that there were "secrets" of the craft shared only by Master Masons. Perhaps this was fostered to some extent by the "degrees" and "mysteries" of modern Freemasonry. Shelby believes the contrary: that masons were only too glad to share their knowledge and even regarded it as a sacred duty. He had it that there was not one big secret in the craft but thousands. And they weren't secrets at all.

The geometry of the Master Mason owed nothing to Euclid or Pythagoras. To give some idea of what is meant here I will paraphrase an example from Shelby's paper. This methodology is from a treatise by the German, Matthaus Roriczer, in the late fifteenth century by which time the invention of the printing press was making the written dissemination of knowledge more practicable. Roriczer was describing how a mason might calculate the circumference of a circle which any of us could calculate in seconds using the formula 2πr. The commentary in italics is my own :

"Make three circles next to one another (Roriczer means of equal radius) and divide the diameter of the first circle in seven equal parts with the letters shown h: a: b: c: d: e: f: g.

"As far as it is from h to a set a point behind it and there put an i. Thereby, as far as it is from i to k, equally is the circular line which stand next to each other..."

Let me paraphrase this. Three circles are drawn side by side, their centre points in a straight line and each with the radius of the circle whose circumference is to be calculated. The mason then draws a line through the centres of all three circles, end to end. Because there are three circles, if he were to measure the total diameter across all three circles end to end, he will have calculated 3*d or 21/7 *d.

But the circumference of a circle is πd and π as a fraction is 22/7, not 21/7. So when the mason adds to the length of his line through the three diameters an extension to the line equivalent to one-seventh of the diameter of one of the circles ("the line from a to k") he ends up with a line that is 22/7 * the diameter: that is 2πr, or if you prefer it πd.

The mason would never have heard of pi and would know nothing of the 2πr formula. By using just his compasses and a ruler, however he was able to calculate the circumference of a circle. How ingenious is that? This is an example of what Shelby terms "Constructive Geometry". That is a very simple example. Rorizcer goes on to demonstrate, for example, how to design the cross section of a stone pinnacle simply by drawing three squares nested each within the other.

Finally, we all wonder at "what they could do then" without modern tools. This is understandable but we habitually underestimate our forefathers. In reality they had mastered the science of levers, pulleys, fulcrums and so on in at least the last three millennia BC, as the Pyramids of Egypt amply attest. Five thousand years is a very short period in the evolution of a species. Our forefathers did not lack our intelligence: they did lack the means to share their knowledge. Hence the importance of the oral tradition of the masons' craft.

|

|

|

|

Pay

Knoop and Jones pointed to the lack of consistency in pay rates between sites and over the centuries. Indeed, this lack of consistency is one of their arguments against the notion that Stonemasons Guilds were widespread before the sixteenth century.

Building work - especially stonemasonry- was unusual in mediaeval times in that the employees were almost always paid by the day. That “day” would occupy all of the daylight hours, and daily rates fell by typically 1d during the shorter days of the year. Although daily pay was a much more secure environment than that enjoyed by many trades, the fact is that when building was impossible in the Winter months then there was no pay at all. We can only speculate whether the men found alternative employment or just “hunkered down” for the Winter in the same way as agricultural labourers. Some or even most masons probably had homes in villages away from the building site where wife and family might have had some form of smallholding. There are, sadly, no records to prove this.

Some work was paid for “ad taschem” - for the task. This does not, however, seem to have been prevalent in church building where most men, of course, were needed for the entirety of the project. There is some evidence that decorative carving was sometimes paid ad taschem, presumably because the best talent could name its price.

In general, hewers were paid more than layers but men were paid according to their skills and not just according to their line of work. Thus, at Caernarvon Castle in 1316, hewers were paid between 27d and 33d (old pence) per week, while layers were paid between 14d and 28d. The predominant rate was about 4d or 5d per day. Data on average wages in mediaeval times in notoriously unreliable but a "journeyman" mason seemed to earn a wage, as a rule of thumb, about double that of a labourer. There is ample evidence that daily rates sometimes - perhaps always - varied between seasons. This simply reflected the hours of daylight available for work. Masons were generally expected to work from dawn until near sunset. They would get an hour for "dinner" and probably a quarter of an hour in the afternoon for "drinking". They would often (hard as it is to believe in England) have a siesta period.

The Black Death led to a general increase in rates, despite the efforts of Richard II and his successors to peg wages by so-called “Statutes of Labourers”. An ordinary mason was to be paid 3d per day, a master 4d. I have commented elsewhere on the meagre premium that master was allowed, although we will see that at Oxford the ordinary masons were being paid 6d per day in flagrant defiance of the statute. This, perhaps, is hardly surprising. The wages paid at Caernavon in 1316 equated to between 4d and 5d per day. With a diminished population of masons after the Plague and a seemingly unquenched appetite for building work Richard’s efforts were rather Canute-like. Patrons needing masons were always likely to contrive ways of getting round the statutes where necessary.

What is very noticeable is that the statutes did not recognise the difference between a hewer and a layer. No doubt this was an attempt to lower wages in general. It also explains why the vast majority of masons at Oxford were referred to only as “masoun”. We need to be careful, however. Not all building at the colleges was on churches by any means and many masons would have been working on a jobbing basis, repairing chimneys, building walls and so on.

London, even then, enjoyed a wage premium. Some things never change! It was not unusual for masons to be found lodgings by the parish. This is hardly surprising. Masons working far from home would not be able to check into a hotel! There is occasional evidence that masons were accommodated in the lodge building on a kind of bunkhouse basis. Food too was often provided. The Statute of 1446 specified 4d a day for a freemason in Summer with food, 5 1/2d without food. In Winter they reduced to 3d or 4 1/2d. A master mason was normally paid around double. The Statutes were frequently breached and it seems that some masons were happy to pay any consequent fines. The Statute of 1495 increased the value of food provided to 2d a day.

It is interesting to compare these imputed costs of food - a penny or three ha’pence per day - with the pay of a labourer of 4d per day (at Oxford) and or 2d (according to the statute). This implies that a labourer unfortunate enough to be employed at statutory rates would be paying maybe 75% of what he earned on food. Again, the rates seem somewhat Canute-like.

When we evaluate masons' wages we need to be aware of the many Saints days and holy days that might be observed. The number would generally be between twenty and thirty. There was no hard and fast convention as to whether the masons would be paid for this down time but Knoop and Jones felt it would be very much the exception. Wages on royal works were sometimes marginally higher but by no means was this always so. What does seem to be the case if that the wages paid for royal projects were less responsive to market forces. This is hardly surprising: as we shall see, if the King couldn't find enough masons he had them pressed into his service!

In all of this you will note that hourly rates and annual "salaries" as we know today were unknown in the mediaeval masonry trade.

There is ample evidence that in the later mediaeval period it was quite common to sub-contract a whole project to a mason. I would go as far as to say, intuitively, that this was the norm where parish church building was concerned. We do not know whether a contracting mason paid his men according to the statutory rates but we must assume that he paid whatever it took to acquire the necessary workforce. We know that the masons at the Oxford colleges were fined when they were found to have been paid more than the permitted amount. Again, though, we must wonder if the same scrutiny occurred outside the towns and whether the record-keeping of a contractor - if any - was the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth!

|

|

|

|

Decorative Carving and the “Imaginator”

So far we have discussed the topic of structural construction: how the work was designed and how it was executed. When we visit churches, however, it is often the decorative work that impresses as much or more than the building itself. We might make a crude distinction between “architecture” and “art”, neither of which would have meant anything to a church mason.

This is not the place to discuss the problematical subject of how and why the artistic elements, if any, were decided upon. We can safely say, however, that few churches in the history of England were constructed with no decorative elements at all. Who did that work? The hewer? The layer? The master? All of those? None of them?

Let’s step back a thousand years and consider the Norman era. The Normans liked decoration. They liked to carve fantastic images on tympani, fonts, chancel arch capitals and corbel tables. The meaning of much of that imagery is totally impenetrable to us today. What is very obvious, however, is the remarkable differences in the quality of the execution. Take a look at the some of Norman fonts and tympani shown on my “Dawdle through Derbyshire page. Now look at, for example, the font at Eardisley in Herefordshire, the chancel arch capitals at Wakerley in Northants. It is like comparing a child’s doodles with Leonardo’s drawings! Corbel tables where carvings are numerous are, with few exceptions, quite crude and repetitious.

This tells us, I think, that some were executed by skilled decorative artists, probably of considerable renown, and some were hacked out by masons whose skills were primarily in construction work. If you want tiling done in your home you can employ a handyman or you can use a man who makes his living from laying tiles. We all instinctively know who is likely to do the better job, albeit perhaps at a higher price.

So I think the answer to my earlier question is likely to be “any of the above”! Decorative carving demands both the imagination to conceive the design and the manual skills to execute it well. It seems unlikely that any type of mason was precluded from a building role by an inability to do these things. On the other hand we might surmise that a man with those skills would be a 76more attractive proposition to a master.

It is known from the few remaining records of mediaeval building work that there were men called “Ymaginators” who had exceptional expertise in decorative work and who could command a huge wage premium. We have to be very careful again because these records were mainly from abbeys and cathedrals. They had the money to pay for the best. Most of the work on our parish churches is under-valued artistically but we cannot compare the quality of the cornice friezes at Ryhall or Adderbury Churches, for example, with that of the “leaf” carvings in the chapter house at Southwell Minster. There is no evidence, however, that the Ymaginator role was a formal one within the masonic hierarchy. We do not know if they were peripatetic or whether they found long-term employment in great cathedrals but the latter seems much more likely.

We don’t have many examples of what sort of money a skilled carver could earn but there are particularly revealing details in the accounts of Magdalen College, Oxford in 1508/9. Twenty five “gargoyles” were ordered and the work was carried out by John Buce and Robert Carver (!), both designated “carver”. The cost of the stone was fifty one shillings, including digging it out of the ground, transporting it and sawing it into shape. That is, around two shillings per gargoyle for materials. Buce made twenty two of the gargoyles and was paid £7 4s 10d. That is seven shillings and five pence per item. If a master mason was paid 6d per day or 3 shillings per week then this was the equivalent of forty-eight weeks of work. Carver was paid 20 shillings (£1) for three – that is six shillings and eight pence each.

They are not in fact gargoyles at all but free standing sculptures mounted upon the half-buttresses and they are very fine indeed. I do not know whether the college recorded them as gargoyles or whether Eric Gee made a mistake. In any event, this was a considerable outlay for the college. Unfortunately we are not really able to calculate what sort of premium these men received because we do not know how long thet were working on them.

It would seem likely that amongst the peripatetic masons’ lodges there might be one or men who could turn their hand to decorative carving. They would, it seems, have enjoyed the status of “freemason”. It is obvious that within the Demon Carver lodge there was generally more than one because most of the churches exhibit more than one quite distinctive style. On some churches this carving is in copious quantities but overall there is not enough and the quality is not high enough for us to seriously contemplate the possibility that they were executed by professional decorative carvers or “Ymaginators”.

Just as masons could move between the roles of hewer, layer and quarryman, however, it is not inconceivable that a mason could at times be employed primarily in a quasi-imaginator role. The mason I call “John Oakham” in my book had a quite remarkable output of carvings on as many of sixteen churches between Leicester in the west and the east Lincolnshire port of Boston. Some of those churches such as Grantham, Sleaford and Boston were rich ones and the quantity of carving was copious. Others, on the other hand, had few carvings. Those at Brant Broughton in Lincolnshire were works of considerable imagination. Those at Oakham itself and at Boston were distinguished by their quantity and not their quality. It is possible – even likely – that the man carved on chancel arches and Easter Sepulchres inside these churches and most of these are admirable. He certainly carved the rather odd font at Muston in Leicestershire where the similarities with his frieze carvings perhaps define the limitations of his imagination.

John Oakham’s work suggests that a mason could carve himself out a role (pun intended!) as a decorative freemason without ever being able to make a permanent career of it. I believe his skill (and possibly his speed) were generally recognised as an asset and that he was sometimes able to command a wage premium. At Brant Broughton and Heckington in Lincolnshire he may even have worked as a full time ymaginator. At other sites, such as Billingborough in Lincolnshire, his corpus of work was small in scale and mediocre in imagination and execution and I am sure that it was just a diversion from a role on that site as a hewer or layer. In general, with exceptions, his output did not demonstrate enough imagination for him to have been thought of as career “Ymaginator”!

The other, perhaps greater, revelations about the career of John Oakham its apparent longevity and the extent of his travels. He survived the hazards of the building site and of the plague sufficient to be have worked on at least fifteen churches – and it could have been more if we suppose that his decorative work was not always called for. Geographically his wanderings were not terribly ambitious to our eyes but John shows the extent to which a mason might have to travel in order to stay employed.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Some of England’s finest gargoyles and grotesques of on the west tower of Great Ponton Church, Lincolnshire and dating from 1519. But what manner of man carved them? A professional ymaginator or a jobbing freemason? The scribe gargoyle (top left) may be the first sculptural representation of reading glasses in England. Is the man (bottom right) a representation of a stonemason?

|

|

|

|

This Article is Continued on a Second Page. Click here.

|

|

|