|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

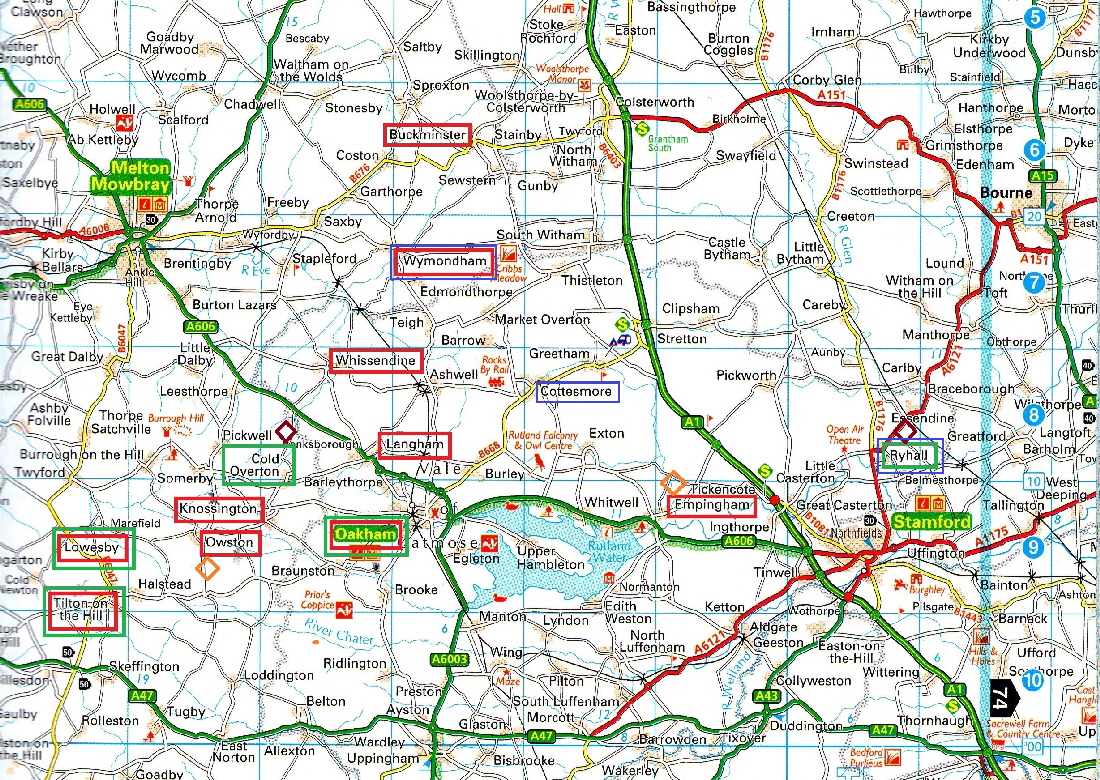

The objective of this study is to prove the existence of a group peripatetic stonemasons. So far we have established trademarks and styles that make that quite certain. For each of the churches with a mooning men carving we have been able to so far identify at least one mason and two at those churches where the Gargoyle Master left his idiosyncratic mark. There are, however, quite a number of carvings that cannot be instantly attributed to any of these masons. Sometimes this is because they are damaged by weathering. We will see Langham has suffered quite badly, for example. Sometimes friezes are bland and could have been carved by anyone. Others have very small carvings that may or may not be miniature versions of those on other friezes. We will not be able to parcel up every course of frieze and point it to one of these five masons. In some ways, this is very much the point. If we are seeing the work of men who did nothing other than sculpt friezes - and I think that unlikely - then we should expect to see just the same men at every location. If however, as I believe, the frieze carving is a “finishing” job in building works that included changes to aisles, clerestories and roofs then any mason who was competent might be set to the task. That competent mason might work on, say, Lowesby Church and then either join another group of masons or simply be passed over for the job thereafter. All, of course, is speculation. It is important, though, to investigate those sections of sculpture that cannot be readily associated with one of the “named” masons”. We will see in the next section that one mason really did like to leave his own calling card. For now, though, I want to focus on the phenomenon of the use of black lead for eyes of grotesques and people. We have seen that Ralf of Ryhall used the device at Ryhall and Oakham. We have seen that the Gargoyle Master used it too. Conversely, there is no sign that it was used by John Oakham, Lawrence of Leicester or Simon Cottesmore. The device is not unique to the MMG churches. It is extremely rare, however, and its proliferation marks it out as a characteristic of the group. When we look at friezes even within the MMG’s geographical orbit that are apparently not carved by the group there are no black lead eyes at all. From ground level it is impossible to make out from what material these eyes are made. Slate was my first thought but this is not an area, of course, where slate occurs. What other minerals are there are that are black, durable and which allow thin slices to be obtained? Flint is a candidate, but this is not an area where flint occurs either. No mason is going to take the trouble to import materials for obscure decoration in minuscule quantities from other parts of the country. I was indebted to a churchwarden at Ryhall Church for the information that it is lead and once you know this the story as how it came to be there becomes very obvious. Many black eyes have been lost, some sculptures having only one. We can’t know if both were lost and it is very possible that all of the Gargoyle Master’s work (gargoyles being in particularly exposed positions) had them. Ryhall is the “spiritual home” of the black eyes so we will start there. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ryhall Black-eyed carvings. The four pictures top left are of labels stops on the south aisle windows. The three pictures bottom right are labels stops from the clerestory/ All of the others are frieze carvings from the south aisle. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

We have seen how Ralf of Ryhall carved wonderful grotesques and the two ”tradesman” carvings at Ryhall, all of the carvings having or having had black lead eyes. Twenty one frieze carvings still have one or two surviving and all are on the south side. There are many complete pairs as well as several where probably both eyes have been lost. Oddly, on the east end of the church and on the north side there are none. Nor does it look like they had then to start with. Four label stops (carvings at the ends of drip moulds) also still have surviving black eyes, again all on the south side. There are at least six more on the clerestory label stops - there is no frieze on the clerestory. Then, we have seen that the same man sculpted seven similar grotesques at Oakham. Lowesby is the other church with quite a lot of black eyes. Ten survive with one or both eyes intact and there are several others that clearly had them originally. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Lowesby frieze carvings with black eyes. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Were the Ryhall and Lowesby black eye carvings by the same man? Looking at them, I don’t think you would immediately think so. If you look at the Ryhall grotesque carvings, however, some are similar in the use of the deeply cut “maned” faces. On some of them, however, connections are vague or non-existent. Like Ryhall, Lowesby does, however, also has a number of label stops with black eyes. And there is little doubt at all that they have familial connection with the black eye label stops at Ryhall. In fact there is little doubt at all that these are the faces of one or more masons and possibly other master craftsmen. The hats that the men are wearing are unlike any peasant headwear depicted in the mediaeval illuminated psalters. These are clearly men of substance. Nor is there much room for doubt that some of those depicted at Ryhall are also depicted at Lowesby. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

The left hand picture is from Ryhall. The Lowesby label stop carving to its right is surely of the same man. The other carvings are other Lowesby label stops which have or have had black eyes. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Second Left: Label stop carvings from Ryhall and Lowesby that, again, are indubitably of the same man. Note the exaggerated skin cleft on both heads and the characteristic soft caps. It has to be a mason, doesn’t it? Centre and Second Right: Badly weathered label stops from Cold Overton Church, Leicestershire. Far Right: Label stop at Oakham Church. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

It is, then, very difficult not to to conclude that the same Ralf who was carving all those black-eyed sculptures at Ryhall was carving those at Lowesby as well. I showed pictures of Cold Overton in Leicestershire too - a church I have not previously mentioned. No black eyes have survived that heavy weathering, of course. Can we find any proper evidence for Ralf’s presence here? The church has a frieze only around its tower. Frustratingly, it was clearly of rare quality and interest but has suffered grievous damage. It also has the unique feature of four large monstrous carvings at ground level of the west end of its tower. And one of them has a surviving black eye and it seems a reasonable assumption that they all did originally. It suggests that some of the grotesques on the frieze may have had then also, although others equally clearly did not. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The frieze carvings at Cold Overton have some images that look like they would not have had black eyes and other that look as thought they might. Note, however, the heavily maned creatures with well-defined claws. Are there reminiscent of Ralf’s heavily maned creatures at Oakham and Ryhall? |

|

This leaves an awkward set of single examples of black eyed carvings at each of Tilton-on-the-Hill, Langham and Whissendine. The Tilton example is very reminiscent of those at Lowesby which is unsurprising as the churches are less than two miles apart. I think we can be pretty confident that Ralf was at both. That at Langham sits amongst a frieze that has been weathered almost beyond recognition. Whissendine’s is one of three buttress sculptures that probably date from known structural damage to the north side of the church and it is by no means certain it is contemporary with the friezes by John Oakham.. None of these three churches has label stops that match those at Ryhall, Lowesby, Oakham and Cold Overton. With some exceptions, stylistic similarities between the groups of black eyed carvings at these churches are elusive. |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

Black eyed carvings at (left to right): Tilton-on-the-Hill, Langham, Whissendine |

|||||||||

|

Although this study is mainly about external carving it is, however, impossible to ignore the presence of black eyed sculptures inside at three churches: Ryhall, Wymondham and Cottesmore. Ryhall is of course, Ralf’s home village and Wymondham has gargoyles by the black eye loving Gargoyle Master. But what are we to make of Cottesmore where there is no sign of the presence of either of these masons? |

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Internal black-eyed carvings on spandrels and corbels: Top Row First Three from Left: Wymondham Top Row: Right and Second Right: Cottesmore Bottom Row: All Ryhall. |

|

None of the interior sculpture is obviously by one of the men who carved outside. Indeed, it looks like there was a different sculptor inside each of these three churches. So in addition to Ralf there may be three more sculptors using the device. At Ryhall and Wymondham we might have led ourselves to believe that Ralf and the Gargoyle Master respectively were responsible but this case is drastically weakened by the case of Cottesmore where neither man was present. What conclusions can we draw? Well, as I said in previous pieces, we are wandering into the land of supposition and inference. We can say quite categorically that the appearance of all of these black eyes is not a coincidence because they are exceedingly rare - I cannot think of another church with even one on its outside. Bear in mind that we have been discussing frieze carvings here. The Gargoyle Master also used the device. In all, then, that is eleven churches, all within a very small geographical area. Then we have the further coincidence of four of these churches having label stop carvings - all badly weathered - that may have be showing the same masons. If we exclude Owston and Empingham that have no friezes at all, seven of the remaining nine have mooning men. Can we say that all of the black eyed frieze carvings were all by the same man? In the cases of Ryhall, Oakham, Lowesby, Tilton-on-the-Hill and Cold Overton I think we can. The three sets of internal carving - especially Cottesmore - suggests, however, that although Ralf and the Gargoyle Master were the biggest enthusiasts, other masons used the device as well: it was something embraced by the group, not just by those two individuals. On that basis we are not entitled to assume that Langham and Whissendine were also by Ralf. But why would a stonemason be dabbling in the dangerous business of molten lead. Well, the answer of course is that he wouldn’t be doing an such thing. That leads us onto the topic of.... |

|

Plumbers and Lead Roofs |

|

What we do know is that lead eyes would have required the presence on-site of a plumber - a worker in lead. We will be discussing later how extending churches gave the opportunity – the necessity even – to re-profile roofs and to upgrade the means of removing rainwater. Even if a church already had lead on its roofs it would still be necessary to rework it. So a plumber will have been needed. Plumbers, however did not just deal with roofs and rainwater goods. They also made liners for fonts and the frameworks that fitted around individual panes of glass in traceried windows.. 5s 3d/cwt is the cost of lead in sheet form at Collyweston Church only four miles from Ryhall in 1504, perhaps a hundred years after the Mooning Men Group were at Ryhall Church. Salzman, however, also suggests óG5 per ton at around the beginning of the fifteenth century so we can be sure we are in the right ball-park. |

|

Ralf and the Gargoyle Master - One Man or Two? |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

We cannot answer this question definitively. For that reason I have always maintained that Ralf and the Gargoyle Master are two different men. It might be argued, however, that if the external use of black eyes is really confined to these men, as I suspect it is, then it seems rather a coincidence that they are also the the two styles that are most similar to each other. Apart from the stylistic similarities, the most compelling argument for their being one and the same man is to do with the career of the Gargoyle Master. Why would a man with obvious ability confine himself to carving gargoyles? Secondly, if gargoyles were indeed all he carved then nine churches did not constitute much of a career. The MMG as a group were at thirteen churches, often carrying out considerable alterations. Their stay at an individual church was likely to have been measured in years rather than months. Let’s be bold and suggest a total lifetime of the group of twenty-five years. How on earth could the Gargoyle Master have made a living carving, say, fifty gargoyles over twenty-five years? Everything points to his having part of the peripatetic team on a long-term basis and taking part in the general building work was well as being a sculptor. That being the case, why would he never carve friezes and if he also carved friezes then why would he not use his favoured black-eye trademark? So there is tantalising circumstantial and subjective evidence that the Gargoyle Master was Ralf of Ryhall. Or vice-versa if you prefer! |

|

|

|||||

|

Recommended Next Section: Styles of Sculpture |

|||||

|

Black Eyes and Lead Roofs (You are here!) Church Building in the Post-Plague Era |

|||||