|

|

Alphabetical List

|

|

|

County List and Topics

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

If you are one of the many Americans reading this site, you might be shocked to hear that Boston in Lincolnshire is very far from being on a par for beauty and culture with Boston, Massachusetts. That it had the highest margin in favour of Brexit than any other constituency perhaps tells you all you need to know about how this once-great commercial centre and port has felt - rightly or wrongly - impoverished by globalisation and mass immigration.

Fallen from grace the town surely has, but the church is a potent and cherished symbol of its former greatness. With five stars, Jenkins makes it one of his top eighteen churches in England and for once I cannot disagree with him. It’s a stunner.

The most immediate thing, of course, is the tower - the so called “stump”, two hundred and seventy two feet high visible for miles by intention. It was added to the church in about 1450 and took seventy years to build. The rest of the church was started in 1309. It is the largest parish church in England. And yet its ground plan is surprisingly - even refreshingly - simple. It has the conventional nave, two aisles, clerestory, chancel and west tower of innumerable English parish churches and just a couple of comparatively under-sized chapels on the north side of the chancel and in the south west corner of the nave. It would be instructive to compare it with one of Jenkins’s other five star churches - Burford in Oxfordshire - which has a bewildering layout created by endowments

|

|

|

|

|

by the town’s wealthy guilds.

Boston’s wealth was by virtue of the status it had acquired by the thirteenth century as Britain’s second port as evidenced by the fact that King John levied a tax of óG780 upon it in 1204, second only to London at óG836. It was part of the Hanseatic League and we will see evidence of this on of the church’s magnificent sixty-two misericords. At one point more than three million wool fleeces per year were being exported from Boston. It was also the main market place for lead England. The flat - and at that time flooded - fenlands around Boston could not be further removed topographically and geographically from the lead-mining areas of England. However, the River Trent, the Roman Fossdyke and Witham Canal and the River Witham itself gave a convenient route for the output of the Derbyshire lead mines that would have been hugely expensive to shift by the cart roads of England. From Boston it could be shipped by sea around the country. It also had the River Welland that could carry lead to the churches of southern Lincolnshire as discussed in one of the sections of my “Bums, Fleas and Hitchhikers” narrative. One guild stood out in the town here - the Guild of Corpus Christi. Abbots, peers, bishops and foreign wool merchants are recorded amongst its members and their wealth surely made a huge contribution to the building. They had a chapel of their own which as probably attached to the south aisle. The Guild was not was not alone, however: the Guild of St Mary maintained an organist, a choir and a grammar school and also endowed a chapel in the east end of the south aisle. John Taverner was possibly and musician and Alderman here.

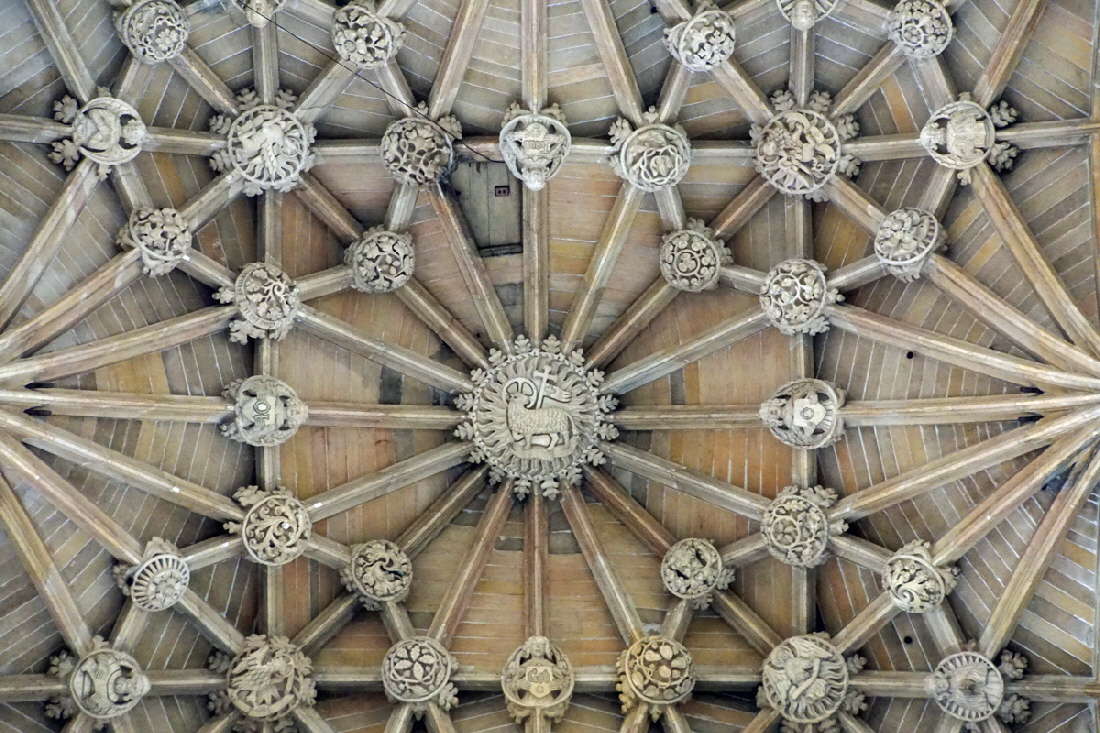

The wealth of the town lad to the complete demolition of the original Norman church, the foundations of which are now underneath the south aisle. The building of the church probably took until 1390 and the tower took a further sixty years. Nobody knows how the tower became know as the “stump”. Could any structure be more inaccurately named? It is not only the overall height that astonishes: the interior has no first floor ceiling so the visitor’s eyes are drawn to the second floor stone ceiling some one hundred and fifty feet up and beautifully adorned with decorated bosses.

Structurally apart from the tower, there is little to excite here. The three westernmost bays of the chancel - where the building started in the traditional way - the aisles and the clerestory have attractive Decorated style windows reflecting the 1309 date. The chancel itself was extended by two further bays in about 1390, themselves in the Perpendicular style that was by now de rigueur. The keen-eyed among you will wonder then why there is then a Decorated style east window? It is a Victorian replacement. Pevsner who could be occasionally droll calls it “glorious” but qualifies his praise “...a copy of the Carlisle east window (in a Lincolnshire church an insult, if in this case not an injury)” . The point being that the Lincolnshire of Grantham, Boston, Heckington and Brant Broughton (to name but a few) needed no lesson in Gothic design from Cumbria! In which observation he was spot on. The trouble is - he was talking out of the back of his head - see below. The south porch is also noteworthy. It is two storey. The ground floor is in Decorated style and the upper floor is Perpendicular, so obviously of a later date. Th upper floor has, since 1634, has held a library of some twelve hundred books of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries but there are also one or two priceless earlier works.

The church has had a lot of alteration down the years, but nothing truly grates on the senses. The simplicity of the interior allows the full magnificence of the church’s proportions to be fully appreciated. It is the chancel that is the star turn here, however. It has cathedral-like fitments. The magnificent reredos was completed as recently as 1914 although it is not immediately obvious. It complements the true treasure of this church: the sixty-two misericords. Dating from 1390 they are one of the most extensive and unspoilt collections in the country. Yes, they do have their share of disfigurement but are largely intact and full of symbolism of everyday and religious life. As if that were not enough there are hugely entertaining figures carved into the armrests. The canopies, however date only from the 1853 restoration but, again, this is not immediately obvious.

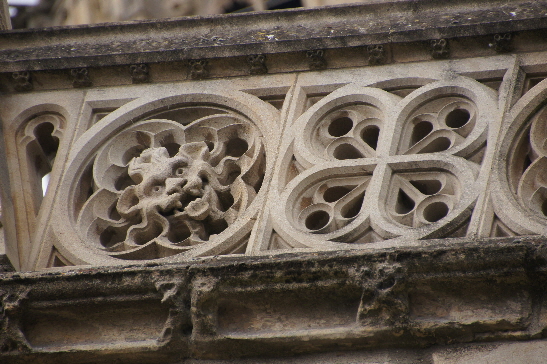

Less remarked upon, perhaps, is the mass of original external sculpture. It is a madcap world that is represented, of grotesques and monsters that we can no longer fathom. In this, Boston is wholly in keeping with the Lincolnshire tradition. Some of the sub-parapet friezes here on the outside of the north aisle (and possibly the south aisle) and, strangely, in the cornice of the cornices on the insides of aisles and chancel are by the stonemason who in my “Bums, Fleas and Hitchhikers” narratives I call “John Oakham”. See the footnote below.

This is a heck of a church, A casual visitor will maybe spend ten minutes on the outside and fifteen on the inside. That is the sad reality of the majority of people who see the magnificence of it all and have no idea of the significance of what they are seeing. In three visits I have seen only myself, my partner and a church crawling friend look at the misericords. You, my dear readers should reckon on a couple of hours at least, Longer if you want to do the trip to the top of the tower. Those suffering from vertigo or bad knees? Don’t even think about it!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

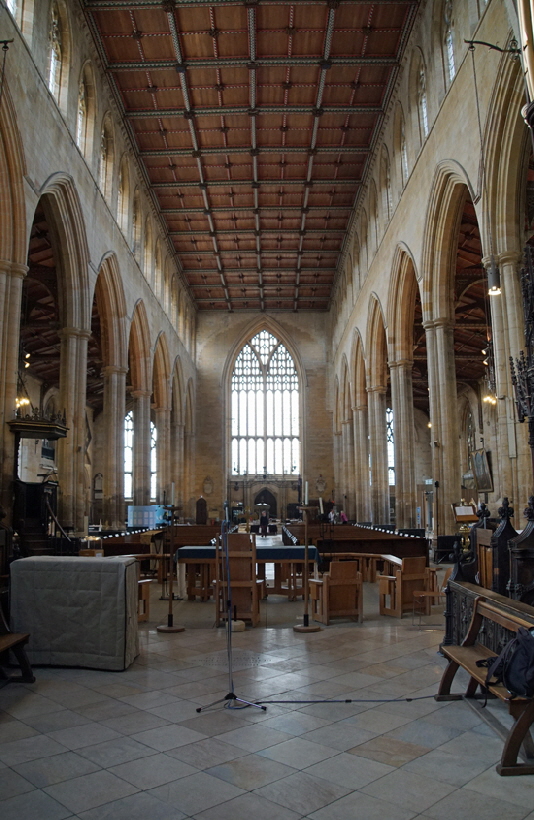

The view to the east end. It is simple ground plan that provides a real sense of space. The high arcades with narrow columns, and the enormous chancel arch adds to the sense that this is almost just two spaces: nave and chancel. The aisle windows are in the Decorated style, apart from the east windows which are Perpendicular style additions. This view would not have been uninterrupted in mediaeval days when there was a wooden rood screen.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Two views of the Stump. Left: The tower from the north east. One of the glories of the tower is its “lantern” top. Why was it there? Well. obviously it would have helped sailors looking for the port but it was also probably of considerable use to the denizens of the hinterland of waterlogged fenlands. This picture shows clearly that the original intention was to stop at the level of the intermediate parapet and then probably to add a spire. But the town in a fit of hubris decided to go further, adding two more stages instead of the spire. Sadly, the fine composition of the double windows beneath ogee arches is far from being emulated in the penultimate stage with its rather utilitarian four light Perpendicular style openings. The masonry is also conspicuously cruder. The lantern, however, is glorious with delicate masonry and tiny flying buttresses, presumably to spread the load to the tower walls and to stop the whole lantern crashing through the ceiling below. Photograph courtesy of Bonnie Killingback. Right: The tower from the east.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Lantern in all its glory. You can see that great pride and workmanship has been invested here, making a curious contrast with the storey below. You can only imagine the challenges and hazards the masons faced in working so high up. And, believe me, any Lincolnshire resident will tell you there is little high ground between here and Siberia! No wonder it took so long to build.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

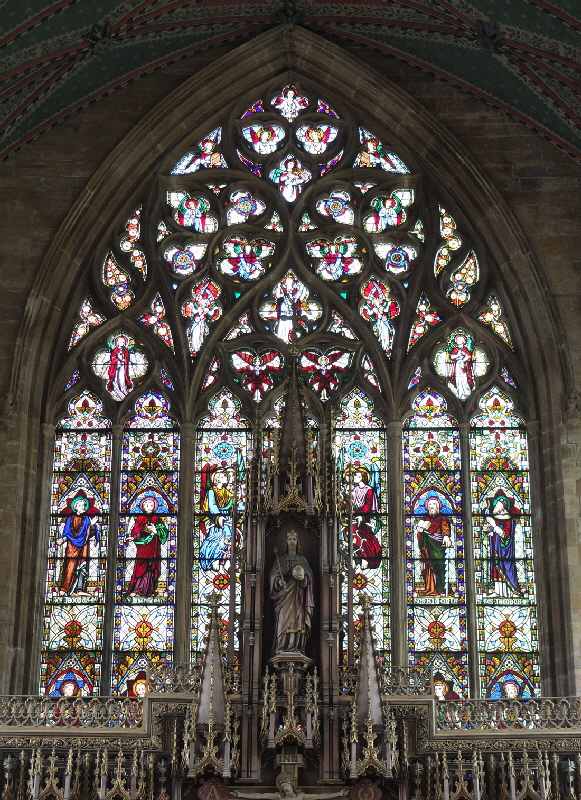

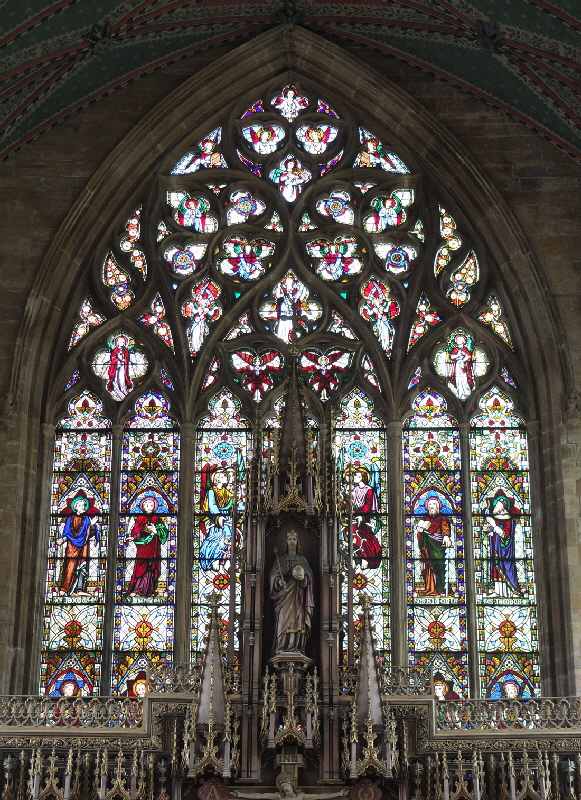

The glorious east end. Note the choir stalls - with misericords - to left and right. The ceiling was added in 1909, Taken as a whole, there is much here that is Victorian: the east window, the choir stall canopies, the reredos, the ceiling. It challenges any “four legs good, two legs bad” approach to church architecture. Nothing here is less than fine and nothing jars the senses: those fourteenth century misericords do not sit within a sea of dross. Much Victorian work is pretty awful. Much of that is the result of the tastes of the congregations and clergy as much as some truly awful “architects” for whom this great swathe of church building and “restoration” must have been a real gravy train. If you could afford the best craftsmen, though, you could get some fine work as here at Boston. I think all church crawlers - indeed all history buffs - have a natural inclination to value more greatly that which is truly ancient. That is perfectly rational, not least because more ancient often equates to grater scarcity. Yet, we have to concede, I think, that some mediaeval work was pretty atrocious too. Norman fonts, for example, can be sublime. Others are crude and child-like. Child-like work by a Norman mason is usually seen as charming. Similar work by a modern sculptor would be ridiculed.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left: The east window is Victorian and Pevsner says it is a copy of Carlisle Cathedral. Quite how he arrived at this conclusion. I do not know. It is not even remotely similar. The glass is of 1853 by M & A O’Connor of London. The Church Guide reports that the novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne said of it “the richest and tenderest modern window I have ever seen”. British readers may be unfamiliar with Hawthorne’s work. His most famous work (I have read it) is “The Scarlet Letter” which is about an adulterer who had “A” branded on her face by the unforgiving puritans of the New World. Hawthorne was a Customs Official in Boston Massachusetts - itself, of course, originally a new World settlement. It seems that is life there inspired both his novel and presumably his visit to Boston in England. Quite how many “modern windows”, Mr Hawthorne had actually seen for comparison is open for question! Right: Carlisle Cathedral east window for comparison. Nicky Pevsner, what had you been smokin’ when you said Boston’s window copied this this one?

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left: A somewhat wider perspective of the chancel with the flanking choir stalls. The reredos complements the “look” to perfection. Right: The south aisle. The Perpendicular style window is by Kempe.

|

|

|

|

Left: The view to the west, The west window shows just how “vanilla” Perpendicular architecture could be. This, however, is a massive window so the great expanse of white glass is to be expected. The tracery, however, is the epitome of blandness. What is not obvious from this picture is that the colossal tower arch is in front of this window which we are actually seeing through the base of the tower! To the right you can just see a set of stalls - also with misericords - for the clergy. There is another set of three on the other side. Right: The fourteenth century tomb of a woman in the south aisle.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

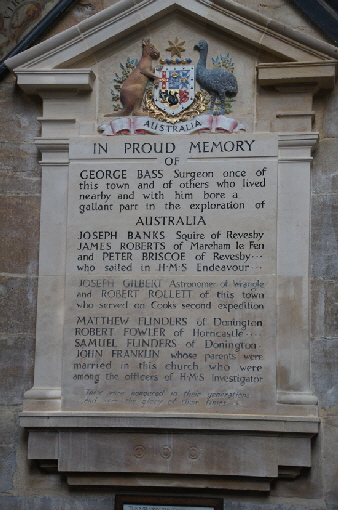

Left: The “Australia Memorial” tablet in the wall beneath the tower. Some of the names commemorated here - Bass, Banks, Flinders, Franklin - echo down through history. I will leave you to Google them! Centre: This, believe it or not is, one of the original south doors. The wooden tracery imitates the Decorated architectural style of the day. Right: There is a heap more pictures to come of the woodwork here but this picture of sheer drollery - taken by my friend, Bonnie Killingback - is a delight. There are shades of green men and jesters but who knows what the carpenter had in mind?

|

|

|

|

Left: There is a great deal of sculpture both outside and inside the church, including this unusually lifelike lion. Right: A triple sedilia plays host to two coloured brass memorials.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

One of the unusual features of Boston Church and one that, as far as I know, has been unremarked upon elsewhere, is that most of the lengths of the aisle and the chancel have internal cornice friezes. This is unusual, to say the least, and Gaddesby in Leicestershire is the only church that comes to mind as having the same feature. Intriguingly, the subject matter changes throughout the church. On the south aisle there is a mixture of cow-like grotesque heads. pigs

|

|

|

|

|

|

heads and fleurons (above and below). The north aisle, however, has almost all fleurons, including long courses of what look like Lancastrian rose motifs (right lower). This is possible as the building took until the late fourteenth century. The chancel - the last place you might expect it - sees a mixture of fleurons and grotesques (right upper). They all seem to be the work of the mason I call John Oakham who is one of the subjects of my “Bums, Fleas and Hitchhikers” narrative. The cow-like grotesques were his main calling card in his work in many churches across southern Lincolnshire. His appearance here, a long way from where I first identified him in Oakham and Exton (both Rutland) and other churches in that area was a big surprise that was subsequently validated by his further appearances at Swineshead and Leverton both close to Boston. We see his work also on the outside of the south aisle here and possibly on other external surfaces.

|

|

|

|

Left: A particularly spectacular St George and the Dragon scene. The dragon is one of the misericord’s “supporters”. We cannot see the saint’s head. Above the horse’s tail is a mysterious head. Right: I am indebted to one of the church’s managers (amongst his titles was “Head of Marketing” which tells you all you need to know about the prosperity of this church) for telling me that this double headed eagle recalls Boston’s membership of the powerful and protectionist “Hanseatic League” of ports.

|

|

|

|

Left: A spectacular sanctuary knocker. It is now affixed to the door of the tower stair but it must surely have once been part of the south door. Any felon grabbing this knocker would have had protection from his pursuers, although not, as legend would have it, indefinitely. It seems a strange and illogical concept to our modern eyes but it had roots back to Anglo-Saxon times and possibly it was first instigated to prevent lords, earls and thegns from summarily executing miscreants without due investigation. Nor should you imagine it was something easily circumvented. Kings regarded the continuation of the practice as part of their royal prerogative and even the noblest of peers could and were called to account by the King should they breach it. Centre: Stained glass in the Cotton Chapel. The chapel is situated in the south west corner of the church. The glass is in fact modern (1939) and the bottom panels commemorate Handel’s Messiah played here in 1807 and the attendance of the American Ambassador at the reopening of the Cotton Chapel in 1857. John Cotton was an extreme Puritan. He was minister at St Botolphs from 1612-33 but became increasingly radical, abandoning some basic Anglican precepts. Facing sanctions, he emigrated to the New World and became a prominent minister in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and found hugely popularity in matters both spiritual and temporal. Right: The nave ceiling.

|

|

|

|

South Lincolnshire had a big tradition of external carving during the high gothic era. It must have been a combination of artistic tradition, patronal emulation and inherited sculptural skills that made this possible. You can see examples stretching from Brant Broughton in the west down through the modern A17 to Boston in the east, taking in the likes of Heckington (arguably the best of all) and Sleaford as well as numerous lesser examples. Pinnacles and - as here - the tops of buttresses were favoured places for such carving and these two examples from Boston could have come from any of a dozen or more churches in this area. The subject matter is common - one might even say cliched - but the effect must have been dazzling before centuries of weathering took their toll. In this respect Boston has suffered quite badly.

|

|

|

|

You can make of these what you will, but for me the concept is that these men always have a devil on their shoulders watching their every move and perhaps whispering encouragement to sin in their no doubt receptive ears!

|

|

|

|

Left: Once again, we must marvel at the ubiquity of green man imagery in English churches, This particularly fine example is at the base of a now emptied-niche on the south side of the church. Right: Who is this man hiding himself behind a hood mould on the south side? My view is that this is almost certainly the image of one of the stonemasons here.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This group of sculpture is, by some margin, the finest amongst this plethora of imagery on the outside of the church. We can see two jesters, an angel, intertwined hares and the finest of green men. They are part of a balustrade on the south side, itself surmounting cornice frieze work. The crispness of the carving and the relatively unweathered stone must make us suspicious that this is recent work but, if so, the sculptor made a remarkable job of emulating mediaeval subjects matter. This is some of the finest external carving I have seen on the outside of any English parish church and, needless to say, has been missed or ignored by other writers. You must make up your own minds as to its provenance but again we are invited to debate whether with work so fine, the era of its execution is very important?

|

|

|