|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

monuments. Pevsner said of them “There are no churches in Rutland and few in England in which English sculpture from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries can be studied so profitably and so enjoyably as at Exton”. Even I would concede that they are impressive. I would add that in my view they are often ludicrously grandiose and in dubious taste but it is hard to argue with the quality of the sculpture, featuring such luminaries as Grinling Gibbons and Nollekens. Sadly, the preoccupation of the architectural commentariat down the centuries with these over-scale geegaws has led to the surviving mediaeval sculpture here being totally overlooked. The chancel has a cornice frieze that has one of the finest displays of grotesque carving in England. It does not get a mention even in the Church Guide. This is another example, I think, of a general contempt for artisanal art. There is absolutely no excuse. The tower was built in the fourteenth century and is accurately described by Jenkins as appearing “telescopic”. It is an elaborate and lofty tower indeed. Its spire is actually quite short so the overwhelming feeling of height here is all down to the tower itself. The parapet above the large bell openings has a cornice frieze with carvings and gargoyles. At each corner of this stage there is a little hexagonal mini-tower, again decorated with cornice carvings. There is another larger hexagonal stage above all of that, similarly decorated . On one of those mini-towers are a mooner carving and a “flea” carving all of which are local fifteenth century conceits that I describe in my book “Demon Carvers and Mooning Men”. - follow this link to read about it . Those carvings are very high off the ground, I took photographs with a long zoom lens. When I looked at them at home I knew they were the work of the stonemason I call “John Oakham”. I knew there would be a mooner and a flea somewhere. I went back to the church, looked more carefully - and there they were. The tower was struck by lightning in 1843 and I quote Pevsner “It (the church) was struck by light and the tower and spire virtually rebuilt”. The carvings and the gargoyles, however, could not possibly have survived a fall from such a height. I did manage to track down a contemporary account (see footnote) and in fact it was the spire that was hit and its debris caused extensive damage to the church, especially its roofs. There is no suggestion that the tower itself suffered extensive damage. Ironically, with the chancel it seems to be one of the only parts of the church that survived more or less intact. |

|

|

|

|

Left: The top stages of the tower. Note decorative cornices below each level and gargoyles on two levels. Centre: Looking towards the east. Doubtless due to the rebuilding there is no sign of any chancel arch. Right: Looking to the west through the tall narrow tower arch. It is a noble look. Pevsner noted that the rebuilt arcades are not symmetrical, suggesting that Pearson’s rebuilding was very true to the original. |

|

|

|

Left: The chancel. The east window is a modern faux-Decorated design. There are monuments to left and right. The intact external cornice (of which much more later) is intact. All of this indicates that the chancel, fourteenth century in origin, was too far away from the tower to suffer extensive damage .Right: This arcade capital has faces carved into it and suggests again that Pearson used what he had and did not reinvent the wheel here. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A Study in three doorways, including (centre) the lovely thirteenth century south doorway. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

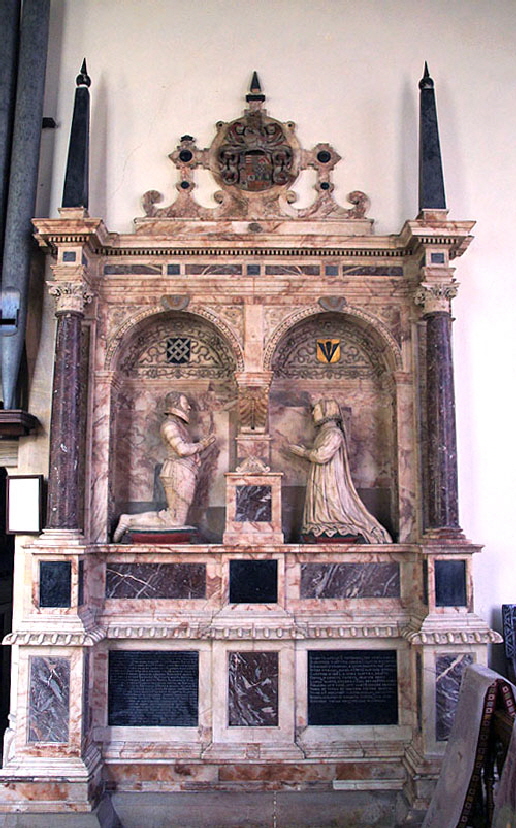

Left: The Kelway Monument of coloured marble is in the south transept. Robert Kelway was a prominent Elizabethan lawyer who died in 1581. To his left kneeling is John Harington, made Baron of Exton in 1603 by James I. He brought up James’s son, Elizabeth, who later became Queen of Bohemia. He married Robert Kelway’s daughter Anne who is kneeling on Kelway’s right. Right: This monument is to Sir James Harrington and his wife Lucy Sydney . Both died in 1592 aged over seventy, a great age for their time. They had eighteen children of whom eleven reached adulthood. The monument is of coloured marble with black marble adornments and the figures are of alabaster. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Details of the Kelway Monument. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

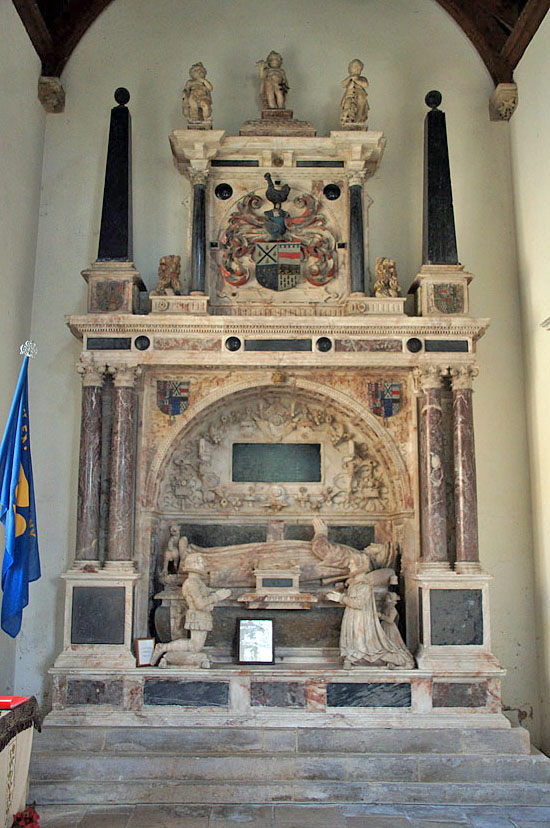

|Left: At the east end of the north transept is this, the most celebrated of the monuments. It was carved by Grinling Gibbon, more famous for his wood carving, and commemorates Viscount Campden with his four wives and nineteen children! It was completed in 1683 and cost £1000. Standing next to Campden is his fourth wife. The ovals to left and right show his first and second wives with their children. The bottom panel shows his third wife and their six children. The panel above that shows the children of Wife Number 4. I can see that the craftsmanship is magnificent but there’s no accounting for taste, is there? Right: This one was carved by another famous sculptor, Joseph Nollekens (1737-1823). It is to Lieutenant General Bennett Noel (d.1771). He is depicted on the urn upon which a woman leans, her right hand holding an extinguished torch. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

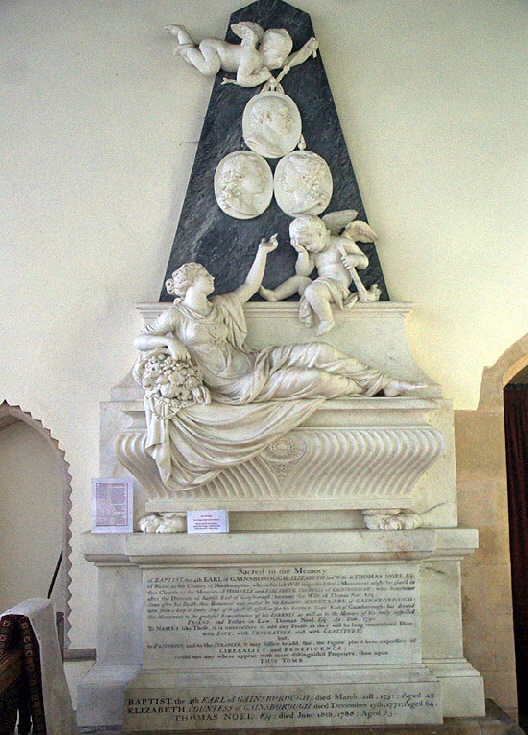

Left: This is another by Nollekens,. It commemorates Elizabeth Chapman, Countess of Gainsborough who died in 1771 and her two husbands: the oddly-named Baptist the fourth earl (d.1751) and Thomas Noel (d.1788). Amongst a sea of eighteenth century pretentious funerary kitsch in English churches (see Elmley Castle, Worcestershire for another prime example), this one takes the palm. What were they thinking of? It’s funny how sculptors get a free pass from posterity. Perfectly-executed rubbish is admired unreservedly, it seems. Right Upper and Lower: More to my taste is this table tomb to John Harington (d.1524) and his wife Alice. The shields are of the Harington and Culpeper families. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This dog is at the side of Alice Chapman (table tomb above). The poor chap has lost a leg. Right: An infant is commemorated on the Kelway monument. |

|

|

|

|||

|

Left and Centre: Matching King and Queen label stops are pretty standard stuff but I thought this pair was particularly fine but I can’t remember on which window they were. I always wonder if such images are intended to be likenesses of the king and queen of the day or whether they are just stylised. I have to say that nobody else seems all that bothered! If they are images of real people how did the masons know what they looked like? It’s not as if they could just open a newspaper! If I had to hazard a guess it might be Edward III. His successor in 1377, Richard II, was clean-shaven (and a bit wimpish) if contemporary paintings are to be believed. If it is Edward then the lady was Isabella of Hainault and she is wearing headwear that supports that. Right: The gargoyles here are rather good, including Humpty Dumpty here. Note, though, that he is not strictly a gargoyle as he no part in dealing with rainwater. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Two more gargoyles. Left: A friend of mine was thrilled when she photographed this one and said it looked like the Duchess in “Alice Through the Looking Glass”. She certainly has a manic look about her. The headwear is bang in period for the fourteenth century. Note the little head poking her head out. I say “her” because she seems to have a lady’s headdress framing her face. This is something of a local peculiarity and there are several examples in my “Demon Carvers and Mooning Men” book. This is no surprise to me because as we will see, at least one of the masons featured in that book was carving sculptures here. In fact, I think he (“John Oakham”) probably carved these gargoyles. Something else to note is that she is carved into the whole of the fairly complex piece of cornicing. It looks like she and just the short length of cornicing attached to her was carved from a single block. I would add that female gargoyles are exceptionally unusual. Right: This one is more “conventional”. Note, however, that like the others here he has large bulging eyes. Looking at the eyes is a useful point of comparison when trying to attribute more than one piece to a single sculptor. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Another unusual gargoyle grasping a rather fashionable-looking guy in one pair of paws whilst pulling a face with his other pair. The carving on the cornice below gives the look of a single carving. Centre: Hmmm! I thought this might be a priapic exhibitionist. They are not unusual around here. I have to concede, though, that it is 50/50 that he is holding a shawm (a mediaeval wind instrument with a bell end) and about to out it to his lips. This carving is hidden high up and in an obscure spot which might give a little credence to the exhibitionist idea. In my experience, however, the sculptors saw no reason to hide such work. Right Above and Lower: A lovely pair of label stop carvings of shy dragons! Couldn’t you just cuddle them? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The fourteenth century font has empty niches that might have been filled pre-Reformation. At the top is a series of human heads which although not esoteric, is somewhat unusual for the time. Right: This picture is here mainly to depict the may layers of carving on the tower. Cornice friezes are on three different levels and gargoyles on two. The top of square stage (the bottom in this picture) has a frieze of human and animal heads. The mini-towers at the corners have friezes with a lot of distinctive grotesque carvings interspersed with ballflower. The top section has only ballflower decoration. It is not easy to make sense of this decorative scheme. It seems as if the higher the tower goes, the simpler the carving becomes. This could reflect that the height of the tower means that the top stage is almost invisible without powerful magnifying optics. The mini-tower carvings are, without any shadow of a doubt, by the prolific John Oakham (I so named him because of the extent of his carving at nearby Oakham, the county town). Probably all of these carvings including the gargoyles are also by him and even possibly the font (he carved one at Muston twenty-five miles away) This picture gives you some idea of the difficulty of photographing the carvings. The various stages interrupt your line of sight and the reverse faces of the mini-towers are invisible from the ground. This is no ordinary tower! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A section of one of the mini-tower friezes. This definitely the work of John Oakham (I emphasise that is a name I made up!). Right of centre is a mooning man in the style of those found locally at several churches (Oakham, Whissendine and Cottesmore are all within a stone’s throw) and undoubtedly the trademark of a peripatetic masons lodge. On the far right is a dog. It could be that this is John’s own dog (Whissendine and Oakham also have dogs). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A series of four carvings on the cornice on the frieze below the square stage of the tower. Note that each section of cornicing has just one carving but that the carving itself is spaced differently on each piece. Thus it was a complex question of carving each piece to the correct length but maintaining the pacing. necessary for the carvings to be at regular intervals. On the mini-tower friezes (picture above) the lengths of cornice are short so the mason carves just one section with all three (or sometimes two) carvings . This must be a complex piece of carving starting with just one length of stone of a square cross-section. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The QED of John Oakham - a “flea” carving. I have found several of these in the area and at the moment my working hypothesis is that the mooning man is a trademark of a group of masons within a lodge and that the flea is a trademark only of John Oakham personally. Again there are examples at Whissendine and Oakham nearby. Right: Decoration on the north east mini-tower. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The south side of the nave. The windows in Decorated style are modern. Note the lead roof. What, you say, is interesting about that? Well. nobody ever called lead attractive. This is probably the reason that as the leading of roofs became widespread it became very fashionable to erect parapets - especially battlemented parapets - around the rooflines. This made the lead invisible. It also created the need for gargoyles and downpipes to stop the rainwater being trapped. Note then that the water from the south aisle here drains into a gutter and through downpipes. The lad is very visible. On the nave roof there is a low parapet but it does not conceal the lead completely. A small gargoyle at each end directs the rainwater through pipes onto the roofs below. Right: One of the nave gargoyles, probably carved by John Oakham. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Chancel Grotesques - and a Rant |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

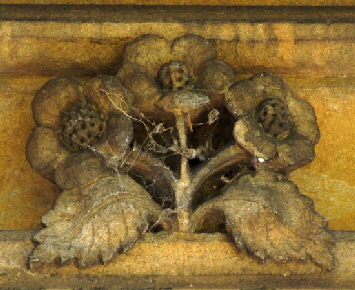

I have spoken many times on this site about the lack of interest shown in mediaeval sculpture by most commentators. Pevsner was notoriously uninterested but we have to acknowledge that architecture was his thing and the books are “Architectural Guides”. I don’t know what excuse you can make for Simon Jenkins except that monuments seem to blind him to most things. Harris’s Guide doesn’t mention them either. In fact, Exton appears in every Gazetteer of English churches and none of them mention these carvings. For the church’s own Guide Book to ignore them is just negligence. I do not know what is behind this. I have seen it written that until quite recently the intellectual elite experienced educational curricula at public schools and the top universities that lionised Latin and Greek languages and culture and that there was no place for anything that was not “classical”. Lest you think this far-fetched, let us remind ourselves why post-Romanesque architecture was called “Gothic”. It was because such architecture was regarded as “barbaric” (sorry Chartres and Wells) and the Goths were barbarians. QED. Except, of course, modern historians have shown that the Goths were not barbarians at all - go to Ravenna if you want proof; and the idea that mediaeval Gothic is in some way by definition inferior to what went before it is beyond laughable. I am not suggesting that the likes of Jenkins think in that way but it is a fact that rather absurd and tasteless neo-classical monuments within Exton Church attract screeds of appreciation while the mediaeval sculpture is ignored, if it is noticed at all. Peculiarly, though, nobody ever overlooks Romanesque sculpture, even when it is often mediocre. There is a whole commentariat that endlessly frets - often nonsensically - about what all that means. You might feel that I have my own bias here. That somehow I cannot discriminate between the craftsmanship of Grinling Gibbons and the sculptural doodles of journeyman masons of the fifteenth century. I can, of course. I don’t, it is true, much care for the principle of over-grand monuments to what I like to call the not-at-all-great and not-very-good but they are there and it is no good viewing history through the lens of modern values and sensitivities. So, no, it’s not philistinism or inverted snobbery. I just think the Nollekens and Gibbons monuments are bad art hiding behind brilliant craftsmanship. They mean nothing to anyone except the genealogist and starry-eyed chasers of renowned artists. Much mediaeval grotesque carving is pretty mediocre in subject and execution. My book and this website is full of it. With some exceptions, such as Ryhall, its interest is in the window it gives us into stonemasonry and building in the post-Plague era. Also, of course to the unfathomable mediaeval imagination and culture. Quantity far outweighs quality. These chancel carvings at Exton, however, are exceptional. We should be able to see beyond the banal subject matter to the quality of the workmanship and the imagination behind it all. Grotesques are always huge fun and the menagerie here is fabulous, literally and figuratively. Unusually, however, what really stands out here is the quality of the fleuron carvings. Petals and leaves are carved with incredible delicacy and deep undercutting. If they were inside a cathedral everyone would be raving about them. As matters stand, this is Exton, a tiny village in England’s smallest county and nobody gives a flying buttress. The Church Guide was last updated in 2002. I do hope that when they get round to publishing a new one the wealth of mediaeval carving here gets its proper recognition. Rant over, I enjoyed that.... |

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

John Oakham |

|

John Oakham - not his actual name, of course - carved at many churches in the East Midlands, as far east as Boston (in Lincolnshire, not Massachusetts!). To see him at his most prolific see Oakham (Rutland) and to see him at his best (and also very prolifically) see Brant Broughton (Lincolnshire) and Leverton (also Lincs). He was part of the Mooning Men Group (MMG) whose work I discuss extensively in “Bums, Fleas and Hitchhikers”, an extensive piece of work you can read on this website. To know more about the “flea” carvings go to “Scratching the Fleas”. For more of John’s work see “The Peregrinations of John Oakham” |