|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

To cut a long story short - probably nothing! A couple of years ago BBC East Midlands contacted me. They had found my website and my little precis of my book. They were interested in running it as a story. I was quite excited, of course, and spent considerable time explaining to the researcher what it was all about. In the BBC way of doing things they then got cold feet and decided to “verify” my story with a bunch of university academics. Then they dropped the story. Those academics, you see, knew nothing about it but as academics it obviously didn’t occur to them to say “Sorry, I can’t comment without more information”. Or “Sorry, I haven’t got a clue”. That’s not what academics do. So they came up with a load of waffle that scared off the researcher’s boss. I said in vain that one of those academics was actually (without knowing it) verifying my conclusions. Well the BBC was not going to risk being sued by the families of unknown stonemasons who died 600 years ago so they pulled the story, having wasted hours of my time. I was sufficiently incensed to find the email addresses of those eminent men and women. One apologised, two said they were given no background by the BBC and the fourth didn’t reply. What did they say? Nothing much, in fact. Their real sin was not to show interest and ask for my contact details. They were “rent-a-gobs” really*. But one theme came out from two of these people: that of apotropaia. That’s a wonderful word calculated to confer an air of superiority on its users. Unfortunately, I know of no alternative word so I am going to have to use it too. My apologies. But what is it? Put simply, it is the belief that evil spirits can be distracted by imagery. So the argument goes like this. To superstitious mediaeval people evil spirits were a reality - which was almost certainly true. They were told that evil spirits (sent by he who must not be named) were always looking to infest God’s house. Therefore, churches needed strange imagery to deflect them or better still to scare them off. By extension the academics were effectively saying “what better distraction than a man baring his arse?” Whole (boring) books have been written about apotropaia. It is, of course, a worldwide and very ancient concept. In many civilisations it undoubtedly was and is a reality. It almost certainly was a reality in mediaeval England too. There are many examples of individual apotropaic signs to be found on the outside of all manner of mediaeval buildings. Think of them as the mediaeval equivalent of putting a horseshoe on the wall of your house. It’s something that people have always done. Apotropaia is a “thing” in England. But was it the motivation for our church carvings? I believe that there are many reasons to doubt it. None of them are to do with cultural history and mediaeval sociology. They are simple logic. Firstly most churches have very little external imagery. Many have none at all. If apotropaiac imagery was a must then most parishes deployed it sparingly and many saw no need for it at all. Apotropaia came at a price that many were unwilling to pay. And why would you do so when a mark scratched on the doorway would do the same job? Secondly, at many churches - Heckington, for example - the volume of carvings is out of all proportion to any such need. Every pinnacle, buttress and cornice is awash with it. If the primary motivation here was apotropaic then the execution of that concept surely went way past that to reflect simple pride. Thirdly, at some places there are many carvings that are obvious scenes of mediaeval life - like the village band. You could still argue that this would constitute a distraction, I suppose. But it was surely primarily for entertainment value. Finally, although bizarre imagery is overwhelmingly more common outside churches than inside, it is by no means uniquely so. I hope, again, that I have convinced you that this whole Mooning Men Group thing was mason-driven, not client-led. I repeat, decorative friezes are very rare on a church. A bit less rare on west towers, it is true, but those are often no more than a few faces and a few fleurons. Half-hearted is the word that springs to mind. Finally, I hope I have put to bed the notion that the mooning men (or fleas) were intended to distract evil spirits! If you choose to accept the apotropaia explanation there is nothing wrong with that as long as you acknowledge it is nothing more than an unproven theory. Explaining a whole decorative scheme as being apotropaic, however, is a very different proposition from suggesting every individual carving had some meaning that was understood by the people of the time but which is somehow opaque to modern eyes. What mason-sculptor would have the time and intellect to sculpt a hundred or more “meaningful” pieces and then repeat the trick a few miles away, reusing hardly any of that imagery? Yet we do see imagery that demands that we acknowledge that the mason must have had something in mind, even if that meaning was knowable only to himself. As always, the danger with sculptural carving is to assume some over-arching one-size-fits-all “explanation”. I would suspect that for any given decorative scheme there were items that would strike a chord with any parishioner, those that were calculated to raise a laugh and sometimes shock in ways that we no longer understand, those that were big pieces of self-indulgence on the part of the mason and a great deal of filler! If all of that amounts to something with an apotropaic function then fine. Something we can no longer understand as a society, I think, is the mediaeval preoccupation with the grotesque. There is no doubt, of course, that mediaeval society was convinced of the existence of not only evil spirits but also of fantastical beasts, as the Bestiaries of the time amply attest. It is a fact that almost every mediaeval gargoyle in England is to a greater or lesser extent grotesque. Ferocity is much less common than wry humour, it seems to me. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Things that meant something to the mason - but not perhaps to us! Left to Right: Cottesmore, Whissendine, Ryhall, Ryhall (again), Brant Broughton. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Mediaeval people loved the concept of the “World Turned Upside Down”. So here we have two images of animals playing respectively a drum and a shawm at Whissendine and Ryhall. Mediaeval people had no problems with being insulted: Third Left to Far Right: Tilton-on-the-Hill, Brant Broughton, Ryhall |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Marginalia |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

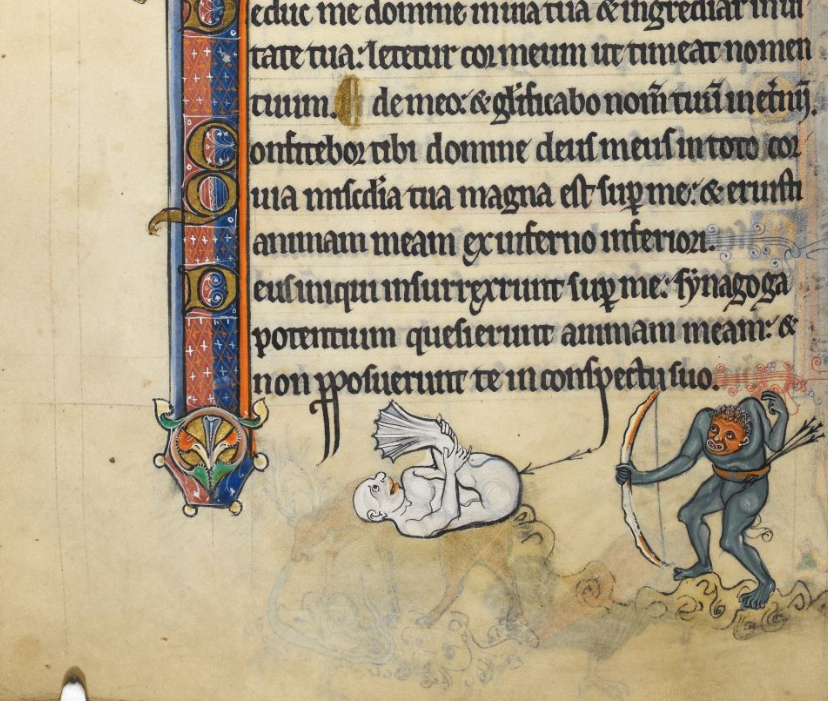

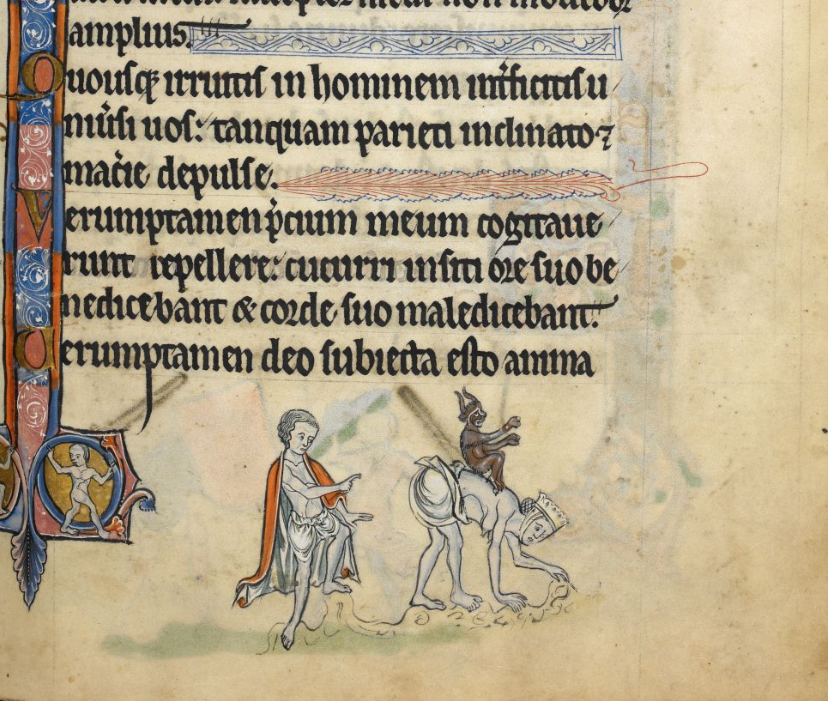

One of the most startling things for newcomers to church visiting is the very notion of rude, crude or at best irreverent imagery. Gargoyles are the usual starting point. You might even see a frieze although even quite experienced church visitors often seem to miss them! After a while you become acquainted with carved capitals, Norman corbels, bench ends, misericords, poppy heads and all manner of seemingly irreligious imagery. None of it seems compatible with Christianity as we know it today. Of course, most people are happy just to enjoy it on its own terms, chuckling at those cheeky craftsmen and not giving much thought to what it is doing there. The best place to start to understand it all is with mediaeval manuscripts and in particular with some of the most beautiful and sacred survivors of the mediaeval age: the psalters. A psalter is a collection of the psalms, often supplemented by a long list of saints days. Such books are masterpieces of calligraphy and illustration and constitute some of the nation’s greatest historical treasures. The cost of such hand-produced books must have been astronomical and only the richest, of course, could afford them. When we look in the margins of these beautiful things, what do we see? Scenes from everyday life, sexual references, scatalogical filth, satire. monsters, grotesques. Does this sound familiar? Now let’s turn to the holiest part of the holiest mediaeval buildings: the chancels and choirs of monasteries. There the aches and pains of the monks attending eight masses in every twenty-four hour period would gain the very slightest respite from misericords that allowed them to rest this weary baksides even as they stood. This was an area of the monastery where no layman would ever go. And underneath those seats, as all readers of this site will know, were scenes not from the Bible but from everyday life. There was not, at least not that I have ever seen, sexual or scatalogical references, but the seamier sides of everyday life were there in plenty. One of the most difficult things for new students of mediaeval life to get their heads around is that the mediaeval people were not at all troubled by the juxtaposition of the sacred and the profane. In a way that we find difficult to fathom, they were not shocked or offended. As we have seen, the scribes of mediaeval documents - monks and friars - were quite happy to entertain their customers with filth and humour. The monks may not have known in advance exactly what Joe the Carpenter was going to carve under their seats but they knew very well it was going to be irreverent, |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Scenes from the Rutland Psalter |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Schoolmaster beating a boy, misericord, Sherborne Abbey. Right: Woman beating her husband, misericord, Carlisle Cathedral |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

For some unfathomable reason, many academics* - especially those multitudes poring over Romanesque architecture trying to link a door capital at Church A in Herefordshire to another at Church B in Tuscany - seem incapable of extending this well-known phenomenon to church sculpture. They want explanations (a friend calls it “explanationism”) and in the absence of anything else fall back on that old canard of “apotropaia”. Here’s a thought for you. If this was a mediaeval concept do you think we might have been bequeathed a more everyday word for it? Yes, I think so too. “Oi, Mason. Old Nick’s about, Let’s ‘ave a bit of apotropaia, mate”. Yeah right. In fact, the friezes of the MMG, as well as gargoyles and grotesques, best serve us as reminders that the common parishioner embraced the spirit of marginalia as naturally as his lord or the local monks. It wasn’t “learnt” any more than you or I have learn that it’s nice to decorate your house. Prof Paul Binski, Emeritus Professor of the History of Medieval Art at the University of Cambridge, gave an enthralling talk about all this on the Churches Conservation Trust website during Covid-19 lockdown ** .His focus was mainly on manuscripts but he answered a question from a listener with very telling remarks about (I paraphrase) “closed group humour” that any office or social group might have: the private humour that is opaque to outsiders. One might say (Paul Binski didn’t) that it is part of workplace culture. As he says, this closed group humour clearly applied to monks. He went on to make much of the fact that mediaeval people saw these things as part of a whole. They did not look at things in isolation as we would, When we think of the masons’ lodge where a dozen burly blokes were eating, belching, farting and wenching together (though not talking about football of course) we are surely talking of the ultimate closed group. That blokish environment surely spawned the mooning men. And it’s a safe bet that the patrons of the local ale houses - another closed group - loved them. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

* I am habitually hard on academics. Well, you know, tall poppies and all that stuff. And, lord, some of them do write some pretentious garbage! A friend once told me that an academic told him that the collective noun for historians is “a hatred”! This is grossly unfair on a few really astonishingly learned people amongst whom I gratefully acknowledge Gabriel Byng (my living hero, as you may have gathered), Paul Binski, and Malcolm Thurlby (the go-to guru of Romanesque architecture). They all have this funny idea that they are talking to people outside as well as inside universities. Also Dr Jasmine Allen of the Stained Glass Museum who managed to wake me up (at last) to the joys of stained glass. See her brilliant CCT talk at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Boq9pH_-uD4. I am sure there are others. Bless ‘em all. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

** You can at the time of writing, watch it here for free. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-UAVodM6HQE. Please think of making a donation to the CCT. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recommended Next Section: The Cost of it All |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Church Building in the Post-Plague Era The Peregrinations of John Oakham What does it all Mean? (You are Here!) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||