|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

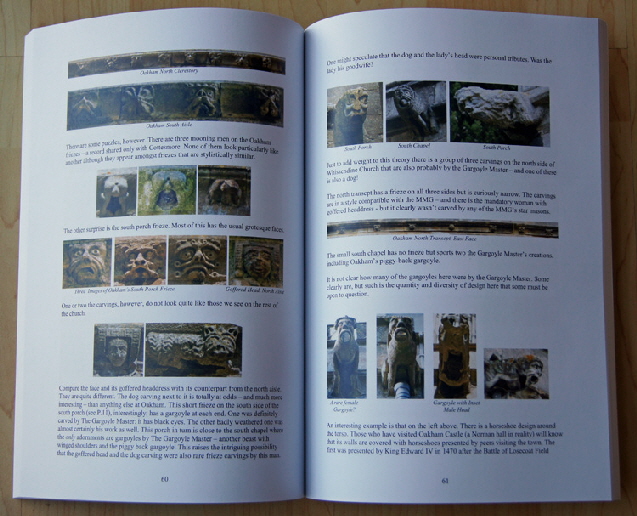

Preface to the Second Edition In January 2015 year I wrote the first edition of “Demon Carvers & Mooning Men”. I commissioned a very small quantity of books and during the intervening period the stock steadily depleted through sales via my website and at a few illustrated talks I have give and through gifts to family and friends. Like many an enthusiastic amateur writer, I suspect, throughout the writing process I wondered why I was expending so much effort. With a subject matter so very local in nature I knew that sales would be infinitesimal and I was proven wholly right in my surmise that even the most local of publishers would decline to publish a book with such apparently limited appeal. I believe that the first edition of my book was the first time anyone had managed to trace parish church masons – as opposed to cathedral masons – across several building projects with any kind of certainty. A great deal of further reading on my part has deepened my conviction that my findings should be seen as an important piece of the very incomplete jigsaw picture of the mediaeval building industry in the post-Plague, pre-Reformation England. Sadly, my interactions with the country’s academics have been a grave disappointment. It is very clear, frankly, that academics wish only to read the work of other academics in an endless cycle of referencing each other’s work. The name of the game seems to be to show how widely-read one is. Many of the comments I have received, although kindly-meant I am sure, have been superficial, often somewhat patronising and all too frequently a bit – how shall I put it charitably? - dull. Listening to enthusiastic amateurs, it seems, attracts no plaudits in the hall of mirrors that is academia. So why a second edition, you might reasonably ask? Since the first edition I have researched heavily into what we know of the modus operandi of the English parish church stonemason. In truth, we know precious little. In the first edition I was much influenced by a book “The Mediaeval Builder and his Methods” by Francis B Andrews first published in 1925 and reprinted in 1974. He was eloquent on the role of the stonemason’s guilds in mediaeval England. A conclusion of the first edition of my book was that there was a peripatetic guild of masons in the East Midlands – I called it the “Mooning Men Guild” – that carved extensively on the exteriors of churches within a fairly limited area between Stamford in the east and Leicester in the west. Since I wrote the first edition I have read an almost forgotten paper written in 1933 a paper by Douglas Knoop and G.J.Jones economists of the University of Sheffield which cast grave doubt about the existence of stonemason’s guilds outside of London until the sixteenth century. Although their work was not incontrovertible it was certainly convincing and I have seen no plausible contrary arguments. Although I remain convinced of the existence of an organised group of masons, I now think that group did not operate under the umbrella of a “guild” as we would think of one. A second reason for this second edition is of new evidence of work by one of the masons “named” in the first edition: the man I called “John Oakham” because of his large body of carving work at the church of Oakham, the county town of Rutland. At the time of the first edition I had also traced John to Whissendine in Rutland, to Brant Broughton in Lincolnshire and to Muston in Leicestershire. Because I was concerned mainly with the collaborative work of this group of masons I referenced John Oakham’s work at Muston and Brant Broughton only in passing. In 2016, however, I unexpectedly spotted more carving work incontrovertibly by John Oakham at the village of Exton in Rutland, snugly within the geographical area of what I must now call the Mooning Men Lodge. Any reprint would be incomplete without references to Exton. Then a hunch led me to the famous Church of St Botolph’s – the so-called “Boston Stump” – in the ancient port town of Boston in south east Lincolnshire where, once again, I saw the work of John Oakham. Further research and many more road miles later I had established a body of carving work that with varying degrees of certainty I can also attribute to John Oakham or, if not to him personally, then to another “Lodge” of which he was part. Apart from personal vanity, to which I freely confess, I was driven to rewrite my account by respect for the work of the late Mary Curtis Webb. Her subject area was, if anything, more arcane than my own. She found that some apparently meaningless decorations on some carved Norman fonts and tympana were not, as had been assumed for centuries, abstract geometric decoration but reflected attempts to reconcile the teachings of Greek philosophers such as Plato and Pythagoras with the Christian (and by implication Mosaic) story of creation. Mary’s studies were deeper, more academic and more wide-ranging than my own by an order of magnitude and I believe that her work was very important indeed in our understanding of first millennium Christian theological belief in England. Yet she never published her work. After her death it fell to her daughter Gillian Greenwood to finally publish her mother’s findings in book form. Like myself, Gillian published privately and to a limited audience, many of whom seemed to have ignored it rather than re-examine their deeply entrenched preconceptions. I was the proud recipient of the last printed copy. Mary Curtis Webb’s work was important yet it could have been so easily lost. Like myself, I think, she became determined to discover connections that are the very nature of history. After considerable soul-searching I have decided that the best way I can respect Mary Curtis Webb’s contribution to our understanding of the Christian mind is to produce a second edition of my own work. Finally, I had fully intended to produce my second edition in paper format. I came to understand, however, after many changes of tack that the internet is a vastly more satisfactory medium since it allows the writer to modify his thinking and conclusions and then to easily make amendments. This has been a voyage of discovery and I do not think I have yet come safely to port! Also the cost of producing this much-expanded edition with its copious amounts of colour photography would mean I could only sell it at prohibitive cost. There’s no point in reaching port with a cargo nobody can afford to buy. LW 6 August 2021 |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

Go To: Introduction |

||||||||