|

accompanied by a change of policy on decoration? Perhaps the comparative flamboyance of the later Gothic styles led to an explosion of exuberance amongst the masons? Whatever the reason, pinnacles, buttresses, parapets and cornices are a gallery of the mediaeval imagination.

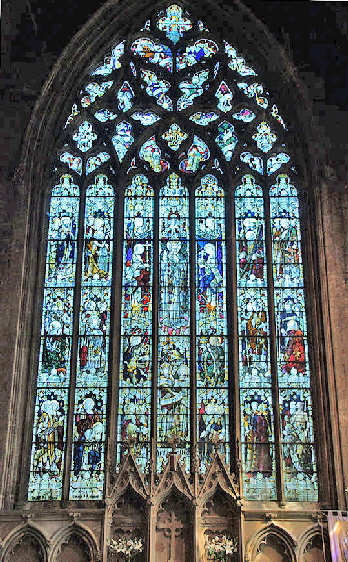

Having said that the church is mainly in the Decorated style, however, this is a church that is not a complete survival from 1307. There were certainly alterations in the later fourteenth century. This, perhaps, was the date of the clerestory which has window designs quite different from those on the chancel. We can say the same about the south aisle. Trying to date parts of a church by windows alone in the High Gothic period is fraught with difficulty, however. We can attribute many - but not all - windows to either Decorated or Perpendicular styles. In the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, however, the styles were freely interspersed. Neither Simon Jenkins (who grants the church four stars) nor Pevsner has dared to try to attribute dates to the various parts of Heckington Church!

The parapets on south aisle and on the chancel are lovely ornate affairs. These we can certainly date to the late fourteenth or early fifteenth centuries because the cornice frieze is certainly the work of “John Oakham” - a name I gave in my book “Demon Carvers & Mooning Men” to one of the masons apparently responsible for many cornice friezes in the East Midlands at this time. Parapets and friezes probably accompanied the leading of the roofs and, if Heckington conforms to the patterns elsewhere in the area, the building of the substantial clerestory.

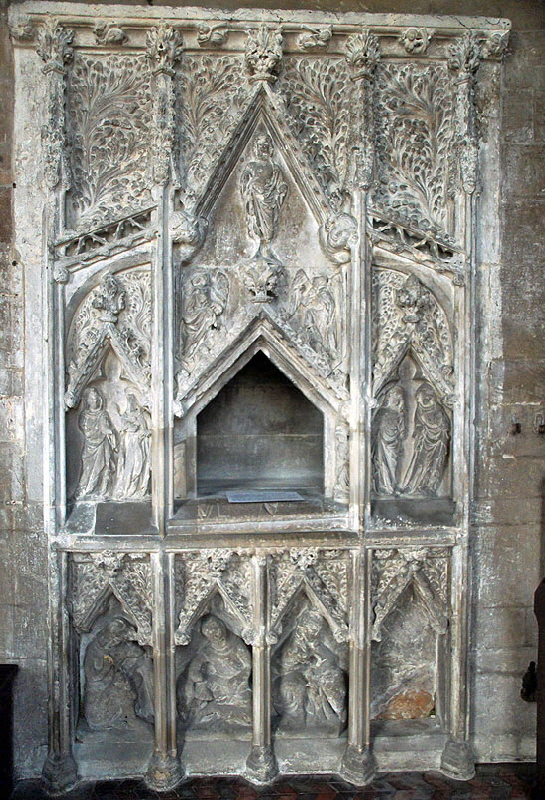

So you can admire Heckington for its beauty and you an be fascinated by its extensive carvings. Heckington’s real claim to fame, however, is inside the church - its “Easter Sepulchre”. It is one of the three finest in England alongside Hawton in Notts and Patrington in Yorkshire. All three are in the Decorated style. You can see a description of the usage of the Easter Sepulchre in my footnote of my page on Coates-by-Stow Church, also in Lincolnshire. Nothing could be more contrary to the anti-idolatry fervour of the Reformation so they fell into disuse, many converted into tomb niches. Those remaining are a real remnant of a sacred rite long gone.

Heckington also has arguably the finest triple sedilia in England. I have more than a suspicion that this, the easter sepulchre and the font were the work of a single mason, possibly even my “John Oakham” who was probably operating as an “Ymaginator” - a professional decorative carver - at this time. It is something I can’t substantiate but the style of these three major church furnishings are all of a very similar style and almost certainly contemporary with each other. What, though, is a sedilia? You probably know it is seating for the clergy - but why three seats? See my footnote below.

|