|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Nostell, Yorkshire. They founded a priory here in 1122. A new chancel was built in the thirteenth century and this is largely the church we see today. In the fifteenth century the clerestories and aisles were added. The priory declined again and did not, of course, survive the Dissolution of the Monasteries. One Francis Shirley was looking for a place to for himself and his family to be interred and bought the priory from Henry VIII. The monastic buildings were demolished but the parishioners successfully petitioned to be allowed to use the monastic church as the parish church. Only the chancel and the twelfth century crossing were saved to form the “new” parish church. The nave was lost completely. The north aisle is filled with Shirley family monuments. Incredibly, rich Saxon carvings in the form of friezes and panels that adorned the walls of the original Saxon minster were preserved through all this upheaval over a period of 1400 years. There are Greek and Byzantine influences to be seen and all of this should help to give the lie to the suggestion that between the departure of the Romans and the arrival of the Normans poor old England went through artistic “Dark Ages”. |

|

|

||||

|

|||||

|

Left: The east end with Early English lancet windows typical of the c13 when this surviving part of the church was constructed. Centre: Looking west to a somewhat untidy west end. When you remember that the whole church here was once merely the chancel - hence its being uninterrupted from west to east - , however, is it any surprise that they were strapped for space...? Right: ...especially when the north aisle is crammed with effigies! Monuments do nothing for me but this Shirley monument of 1598 is a lavish one, and we should not, perhaps, begrudge immortality to the saviours of the church and its treasures! |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

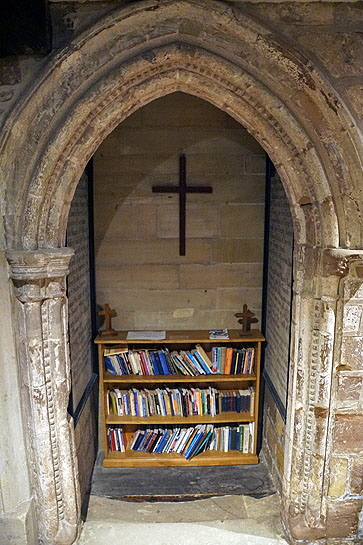

Left: On my second visit to the church in 2019 I was leading a group and we found the church closed! Frantic phone calls and a very accommodating lady vicar resulted in another clergyman rushing from Ashby-de-la-Zouche to let us in, which was above and beyond the call of duty and for which we were very grateful. The gentleman offered to take us into the tower to see the famous “Breedon Angel” (there is a copy in the nave) which was a thrill that more than compensated for our short wait. This is a full-length sculpted “portrait” of the Archangel Michael. It is probably the earliest representation of an angel in England and one of our finest surviving pre-Conquest sculptures. It is indisputably of Byzantine origin because we see the angel touching his thumb with his third finger. The folds of the angel’s clothes are also delicate in the Byzantine tradition. How old is it? I have seen a date as early as the sixth century claimed for it this is fanciful. Eighth century is much more likely. Centre: What is now the west tower was originally the central tower of a cruciform Norman church. Within it there are doorways and blocked windows such as this one that now rather bizarrely houses pieces of armour! Right: This is an internal doorway within the tower complete with the usual Norman chevron moulding but also showing a remarkable narrow and bulbous profile. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Most of the carvings - the finest in England - are fragments of external friezes from both inside and outside the original Anglo-Saxon church. The recent Church Guide by Brian C.J.Williams is wonderfully informative about the carvings and he says that there sixty three feet of frieze in all. In saying “Anglo-Saxon” we must remember that it would be more accurate to say “Mercian”, for Breedon was within that kingdom. Of course, the carvings are re-positioned. At the east end of the south aisle (left) is a set of human carvings, while to the right you can see others of different style and subject matter. Right: This half figure is flanked by two sets of three apostles. We don’t know who the figure is but there is strong support for the notion that it is the Virgin Mary. Once again we see the Byzantine benediction and linear pleated robes. The eyes are drilled whereas those of the Breedon angel are not yet the archways enclosing both figures are very similar. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Three saints or apostles. - and I love the moustache on the chap on the right! It is suggested that this panel (and its companion set to the right of the central figure) would have adorned a stone coffin. Right: The largest of the Bredon carvings: a lion on the south wall. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This section of frieze on the south wall can be divided into three: a series animals biting and generally cavorting with each other. a small panel of “key” pattern, and finally a group of birds. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left Above: The intertwined animals. There is an unusual delicacy about the figures. The legs and tails are long and spindly. To the right one animal sinks his teeth into the neck of another but it is not possible whether the artist meant to convey viciousness or playfulness. Left Below: A similar melee of intertwined birds. Right: One of the more elaborate panels. This one is believed to be ninth century. The men are either swinging censers or holding some kind of branch or staff. Compare the ovaloid terminations to these censers with the terminations of the animals in the frieze immediately to the left. Spot any similarity? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This is another view of the melee of birds. As you can see, the end of the piece is also carved with shell-like designs. This obviously, then, was an end section of frieze-work. Right: I love this little devil peeping out from a joint in the masonry. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Rather bizarrely we seem to have a leg descending here next to a couple of amphora and a box. It is so sophisticated that some believe it to be Norman. There has been speculation that it is part of a larger sculpture depicting Christ’s turning of water into wine. Right: A saint or Christ with a hand raised in blessing. This was clearly part of a larger composition. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Not all of the friezes are historiated, This is a section of th every fine and varied lengths of “vine-scroll” carving behind the high altar. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This is a fine example of inhabited vine scroll - where figures are contained within the tendrils, in this case birds who are enthusiastically pecking at the grapes - and enduring motif throughout the middle ages. This section of frieze has been incorporated into the south side of the tower arch. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Many of the sections of frieze have been mounted very high up above the arcades. This means that you need binoculars or telephoto lens. Even then it is not easy to manipulate an image to properly discern the detail. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Turning a picture into its negative can be a useful way of extracting more detail. As you can see more clearly here, this is a section of vine scroll with men sitting inside clasping the tendrils. The figure second from the left might be holding a spear pointing towards the right of the sculpture. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I’ve used the negative technique again to try to bring out the detail in this piece of frieze - quite successfully, I think. The animals are quite clearly discernible and a fine set they are too. They appear to be entangled with tendrils emanating from rooted trunks (four showing here), although this far less clear |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

One of the great benefits of being able to visit the tower is that the church has a west gallery and it allows much closer view of the friezes mounted high on the arcades at this end of the church. When you look at how finely these are carved, do remember that they predate the invention of the chisel. Left: This is my favourite. On the left is a cockerel, with his head comb making identification very simple. On the right is a warrior kneeling and holding a spear, a reminder that Anglo-Saxon society was both pastoral and martial. Note the naturalistic appearance of this muscular man. Right: Two eagles face each other. Again, they are very Byzantine-looking and reminiscent of the eagles (albeit facing in opposite directions) that characterise the Orthodox church that was spawned by the Byzantine Empire. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Another particularly striking fragment that shows a number of centaurs sashaying through the vine scroll. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Two sections of vine scroll inhabited by animals. They are clearly from the same section of frieze and probably of the same section as a t least one of the sections shown earlier on this page. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

These five images above are are sections mounted beneath the tower and there is a change of mood with more Hellenistic-looking geometrical shapes. The most interesting panel, perhaps, is top right but it is difficult to make out what these human figures are about. The one on the left is seemingly pulling another away from a central somewhat emaciated plant! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Two more sections of frieze before I change the subject! Left: A beautifully carved geometric piece. This looks to have been the left hand end of a longer piece of frieze. Right: A length of uninhabited vine scroll from beneath the high altar. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This section of frieze is located on the north east corner of the church. The interlace ornament is finely carved but the greatest interest here is provided by the magnificent figure of a mounted warrior holding a spear and charging into battle. Note the accuracy of the horse’s legs. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Right: details from the Shirley monument. Francis Shirley is unusual in that he doesn’t seem to have done anything very interesting besides buying the church from henry VIII in order to find himself somewhere to be interred! No scandals, no arrests, no recusancy. A bit boring really! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The Shirley pew - almost a separate room within the church! The arms above it show a date of 1627. The Church Guide, with endearing accuracy, calls it a “Monstrous item of privacy-seeking furniture (that) once squatted in the body of the church completely dominating the seats of less mortals. If nothing else it shows us the social distinctions of the age”. I couldn’t have put it better myself. Right: Breedon-on-the Hill’s Anglo-Saxon legacy also includes a selection of cross fragments housed in the west end of the north aisle. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This fragment is quite fascinating, The lower panel is a fairly routine representation of Adam and Eve and the Tree of Life. The upper one has this remarkable explanation in the Church Guide: “ ...a warrior being offered a drinking horn from a hooded figure probably meant to be sitting on a bench to the left. the warrior may be handing over a scroll of credentials. I is very like the pagan entry to Valhalla. The carving is rather late, possibly Danish period...” I have no idea whether this is true. Other explanations I have seen very tentatively advanced is that the item being held is Adam’s rib from which Woman was created (the only merit being that it would fit on with the Adam and Eve theme) and Abraham raising a knife to sacrifice Isaac. This is all outside my knowledge set. If the Valhalla explanation is correct then this would be a priceless example of Christian and Viking imagery existing side by side such as can be at, for example, Dearham in Cumbria or on many crosses in the Isle of Man. Support for the notion could be argued on the basis that Mercia was the most recalcitrant of the great Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in converting to Christianity and that nearby Repton was the first overwintering location for the Vikings for some of whom Christ was just another god in their large pantheon. Centre and Right: We can also see Saxo-Viking fusion in this cross base. Here be dragons! This is Jellinge style Viking carving. For more on this see Ellerburn. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This was uncovered in 1959, It had been used as a staircase stone. It comprises only geometric decoration. Centre: This Norman doorway - we have to remind ourselves that the priory church structure we are seeing dates largely from 1122 - is sited unusually in the north wall of the tower. Its lozenge decoration is fairly unusual and it is possible that the jamb stones are re-used Anglo-Saxon Right: A Norman window on the south side of the tower. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The tower gives us clues to the nature of the pre-Reformation church. Left: The north side, showing the small Norman door. You can see a gabled roofline to the right and the doorway, then, probably led to a monastic building, Its removal seems to have necessitated the addition of the rather ugly buttress. Centre: The west side where we can see the remains of a rounded arch. This would have been the archway through to the original parish church west of the tower. Much higher up you can see the roofline of that church. The window, therefore, would have given a view not to the outside but to the inside of the parish church. To the right is the present south porch. Right: Close up of the ground floor of the west side of the tower. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The north side of the church. Immediately to the left of the tower you can see an Early English lancet window and below that a blocked doorway. The lower half of the window was originally itself a doorway that would have led in from the monks’ dormitories into the church at first floor level and the monks would have descended down the now-lost night stair to their church for nighttime masses. The later Gothic windows are a hotch-potch of styles, Right: The church from the east shows a fine hand of Early English style lancet windows but the triple array over the altar are modern restorations. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This doorway in very obvious Early English style and now blocked by a wall beyond led into the south aisle from what would have been the south transept.. It is now within the south porch which gives access to the church through the south door to its left. Centre: This lovely carved chair is in the south east of the church. Right: Part of the fine octagonal fifteenth century font, What became, one wonders, of the Anglo-Saxon font that would have been originally here? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote - The Carvings and the Saxon Minster |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The importance of the carvings are Breedon is hard to overstate. We don’t have a huge amount of pre-Conquest sculpture left. We have many cross shafts from that period. Those at Bewcastle and Gosforth - both in Cumbria - and at Ruthwell in south-west Scotland are awe-inspiring survivals of that. period. The Isle of Man has its own extraordinary collection of Celto-Scandinavian crosses. Scotland has many Pictish survivors. Then there are one-off sculptural survivors like Breedon’s own “angel”, others at Deerhurst, Brixworth and Bradford-on-Avon and a whole little gallery of them at Daglingworth. It is true to say, however, that what remains of our pre-Conquest churches cannot give us a full picture of what an pre-Conquest decorative scheme might have looked like nor, if we had such a picture, how widely they were applied. We must never forget that the fractured and fluid nature of first millennium politics legislated against any notion of national “style” in any form of art. At Breedon alone we are seeing probably Hellenistic, Byzantine and Scandinavian artistic influences. We have always known that the political landscape was complex but only comparatively recently have we begun to understand that trade and cultural exchange was also much more international than we had once realised. Breedon’s is the only substantial stretch of Anglo-Saxon frieze we have. There are fragments of what were probably friezes at Edenham in Lincolnshire and at Deerhurst in Gloucestershire. Fletton in Peterborough has fragments of friezes that were, by common consent, of the same “school” of those at Breedon. Castor in Cambridgeshire is also said to have a sculpture from the same school. I am not convinced myself, but far more learned people than myself have said so and I am sure they are right. Unsurprisingly, all three were within the Kingdom of Mercia. How many other churches has friezes of any kind, let alone by this “school” we cannot know. Breedon’s carvings are startlingly fine as well as startlingly numerous. The friezes are fascinating in that Christian symbolism - such as vine scroll - rubs shoulders with warriors. The tradition of mixing secular with sacred, temporal power with religious power on sculpted art begins right here and never really went away until the Reformation. So Church and state co-existed in a quite symbiotic way until one party or the other - usually the Church - got above itself and was slapped down by, for example Henrys I and VIII. Of course, the English Civil War might be seen as the same in reverse but that was, to say the least, “complicated” - as civil wars always are, of course. So who carved these beauties at Breedon-on-the-Hill - without a chisel? And why? As to the “why” that is the perennial question about church decoration. It seems that mankind has always felt the need to decorate the places he lives or worships in. It’s a simple answer but surely the right one. We can’t know “who?” because whoever “they” were they didn’t leave records. Two things stand out about the Breedon sculptures: the craftsmanship and the influence of Byzantine art. Art historians can write whole books about what sets Byzantine art apart. We don’t need to understand all that because we can see that the Breedon Angel and the Breedon Virgin are unquestionably making gestures of benediction, touching the thumb of the right hand with the third finger. So we can all show how clever we are, nod sagely, and say “Ooh, yes, Byzantine influence there” and impress our friends who anyway don’t give a fig! But where does the Byzantine influence come from. Come to that, who were the Byzantines? The Byzantine Empire is the outcome of the decision of Constantine the Great to make his capital in what was then an obscure backwater and which was to become the the greatest city in the in the world - Constantinople. The unwieldy Roman Empire was split it into two geographically with separate rulers, although Constantine himself maintained hegemony over the two. Constantine made Christianity the state religion of both. The Western Empire fell, as we all know, to the so-called Barbarian tribes. The Eastern Empire did not. In AD527 the Emperor Justinian came to power in Constantinople. He built the most magnificent church in the world at Constantinople - the Hagia Sophia - and set about reconquering the lost lands of the Western Empire with very limited success. The Eastern Empire was now what we call (but they didn’t!) the Byzantine Empire named for the original site of Constantinople. Unsurprisingly, the culture of Byzantium was markedly different from that of the remnants of the Western Empire. The Western Empire did not revert back to paganism. The historically maligned Ostrogoths who dominated what we now as Italy were cultured and in, a way that puts Roman Christianity to shame, religiously tolerant - but Christian. You can still see the magnificent cathedral built by Theodoric the Great (reigned AD 493-526) in Ravenna which he made his capital. Christianity still held sway, then, in most of formerly Roman Europe. The Byzantine Empire, however, was infused with Greek - “Hellenistic” - culture and language whereas the west adopted Latin as the common language of Christianity. What could be more conducive to misunderstanding and rivalry at a time when Christianity was still periodically torn apart by differences of theological belief? The head of eastern Christianity was the patriarch and he was appointed by the Emperor. The Pope who ruled western (or “Latin”) Christianity was appointed by the Church and came to see himself as above temporal rulers. Nevertheless, the two branches of Christianity rubbed along until AD1054 when the Great - and irrevocable - Schism occurred by a difference in the liturgy that we would find difficult to understand today. One important difference even while the two branches were tolerating each other, however, is the issue of icons - those paintings of Christ and the saints that still defines eastern Orthodox Christianity in the eyes of most of us in the west today. This all goes back to the Second Commandment that forbids the worship pf graven images. This was uncomfortable to the descendants of Greece and Rome who had happily represented their pagan gods in picture and stone. How was Christianity to square the Commandment with the age-old instinct to see images of one’s God? For the eastern Church the answer was through the icons that were two-dimensional and not, therefore, strictly speaking “graven”. To eastern Christians these icons were and still are venerated as the very embodiment of their saints. They are accessible to the people who feel that they thus have a clear path to communing with their God in the here and now. Latin Christianity, however, not only played fast and loose with the Second Commandment - and still do on an industrial scale - but ensured that access to to God was channeled strictly through the clergy. On such a matter, of course, was founded the second great Christian schism between Protestant and Catholic. Byzantine sacred art then was embodied in the art of the icon and the artistic traditions that underpinned it all was Greek. The icon, however, had its own crisis. With Byzantine territories falling like dominoes to races and tribes that had embraced the new-fangled religion of Islam, the rulers of the Byzantine Empire looked for answers. Why had God forsaken them? Between AD726-87 and again between AD814-42 icons were forbidden and destroyed; which is where we get the now more widely-used word “iconoclasm” of course. To paint an icon was to risk death. Well I hope you’ve enjoyed this history lesson and my apologies for any errors in this potted account. Why have I put you through all this? Well, as you can now see, Byzantine art had Greek roots. Relationships between the two branches of Christianity were strained and they rivaled each other in taking their beliefs to pagan lands. Why on earth then, did Byzantine art influence sculpture at Breedon-on-the-Hill and Fletton - to name but two English churches? Professor Sir Diarmaid McCulloch (I expect my own knighthood to be conferred any day) - our greatest living authority on the history of Christianity - suggests that it came via manuscripts. That is a very obvious channel. After all, Breedon was a monastery and they would have had books. Two things bother me, though. Even if western church artists were influenced by their eastern counterparts in term of style and technique, why would they copy the benediction of the eastern Church? Would it even be acceptable to do so? When the Mercian craftsmen were perusing books with Byzantine art (sounds a bit far fetched, doesn’t it?) would the monks not have pointed out the pitfalls of slavishly copying Byzantine work - especially with something so everyday (for them) as how to give a benediction? So I ask whether the sculptures might not have been created by Byzantine artists; perhaps by Byzantine artists who could no longer work in their homelands as religious artists? Artists who did not understand the fine differences between the symbolism of two brands of Christianity and just created what they had always created. Artists from a church far in advance of its Latin counterpart in matters of art. We cannot date the carvings definitively so in my opinion it is a distinct possibility that exiled Byzantine artists came to England and even Professor McCulloch would not rule it an impossibility. Perhaps the royal house of Mercia gave them succour? Perhaps. I have to admit to a counter-argument of my own: did Byzantine artists have much of a tradition in sculpture as opposed to painting? So just perhaps. Apart from the quality of the sculptures - they are, if I might permit myself a little pun, iconic - there is a lot of it. The friezes were nine inches wide and made in eighteen foot sections and probably adorned both the inside and outside of the original monastic church. Obviously, we have only fragments remaining, Interestingly it is now widely believed that the lengths showing above today’s arcades are in their original positions: that is that the arcade walls were part of the original church. Nevertheless, it is something of a mystery as to why so much of what was displaced by demolition and rebuilding was preserved. I can only surmise that the unique quality of the sculpture has been recognised and valued by many generations of church custodians. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||