|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The ancient Kingdom of Northumbria was the cradle of the Christian church that we know today. It was at the Synod of Whitby in AD 664 under the auspices of Oswiu that the decision was made that the Christian North of England should follow the Roman rather than the Celtic model of Christianity. This was a landmark in British history. Kyneburgha, therefore, was at the centre of the foundation of the Christian church as we know it. By 654 King Penda’s son, Peada, married King Oswiu’s daughter, Ahlflaed. So here we have the two dynasties linked by marriage of two sets of siblings. Oswiu made it a condition of this second marriage that Peada convert to Christianity. Peada returned to Mercia as sub-king of modern Northants and Leics and may well have settled at Castor. The dynastic marriages did not prevent further war between Oswiu and Penda and in 654 or 655 Penda was killed at the Battle of Winwaed. The location is unknown today but Winwaed was probably a tributary of the Humber. Oswiu spared Peada (who had not been involved in the conflict) and between them they founded the first Mercian monastery at Medehamsted - modern Peterborough to whom Peada gave his name. Ahlfrith had been alongside his father at Winwaed but is known to have also made attempts to usurp his father. This may account for his unrecorded “disappearance” from history. It is probably following this death that Kyneburgha arrived at 664 to establish a convent for both men and women at Castor, possibly aided by another brother - Wulfhere - who had succeeded Penda who had been murdered - possibly by his wife! Just to cap it all, Kyneburgha’s successor was her sister, Cyneswith, who “might” have been married to the legendary King Offa of Mercia. She also was declared a saint. Phew! Thus we see that Castor not only had great significance in the Roman era but was also part of the dynastic and religious upheavals of the Anglo-Saxon period. It is known that Viking raids had ruined the fabric of Castor Church by 1012. The Normans rebuilt the church, re-using some of the Saxon fabric especially for the nave, and it was re-dedicated on 17 April 1124. Some Anglo-Saxon long-and-short work survives on the north side. This re-building gave us the nave, the remarkable tower, most of the transepts and the capitals that we see today. Between 1220 and 1230 the South Aisle and chancel were replaced and the porch added. The chancel gained Early English lancet windows but the aisle arches remained almost round-headed, possibly to avoid complex changes to the church’s overall geometry in this “Transitional” (between Romanesque and Gothic) period of church architecture . We know that the Norman west door was blocked at this point and it is speculated that it was reconstructed as the present south door. The south transept was extended between 1260 and 1270, but again we see Norman style being utilised. Was this architectural conservatism or simply a wish to retain a “wholeness” in the structure? I rather like the idea of the architect rejecting “that new-fangled French rubbish!” The north aisle and spire were added in the Decorated style between 1310-1330. The rooflines were made more shallow around 1450. The “angel roof” dates from this period as does the perpendicular style east window. The angels have been repainted in startlingly bright colours but these are claimed to be true to the original. The wonderful wall painting of St Catherine - complete with wheel - in the north transept also dates from c14. |

|

|

|

|

Left: The Norman south door. Centre: One of my favourite compositions at this church: the priest’s door surmounted by the dedication inscription. The doorway is part of the 1220 reconstruction and despite the round arch the doorway is Early English in style rather than Norman. Right: The dedication stone, itself. The Latin wording means “The dedication of this church was on the 17th April 1124. |

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the chancel. The north aisle is Decorated period and the south aisle’s bays are Transitional despite being built in the early English period. At the end east end of the north aisle (left) is the shrine to St Kyneburgha. Right: Because it has a central tower and is therefore a “cruciform” church, Castor church has a “crossing” where huge arches give out onto transepts, chancel and nave. This is a view to the west of the church from the entrance to the chancel. The space below the vaulted ceiling is used as the Choir. Each of the round Norman arches has wonderfully-carved capitals, of which very much more anon. |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Left: The arch from nave to the crossing. Some of the ribs of the vaulted ceiling are visible. Castor’s Norman arches are themselves quite plain - the capitals are decidedly not so! Note the blocked doorway above the arch. Centre: Looking through to the Lady Chapel from the south aisle. There is another Norman doorway and above it a fragment of a Norman window. Right: St Kyneburgha’s shrine. Note the figure of Christ above and to the right of the altar. |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Left: A fragment of an Anglo-Saxon cross mounted in the north aisle. It is believed to be a re-used Roman pagan altar. Around the base are dragons. Right: Chancel south wall. On the left are the Early English piscina revealing, again, nostalgia for Norman decoration. To the right are the large sedilia. |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

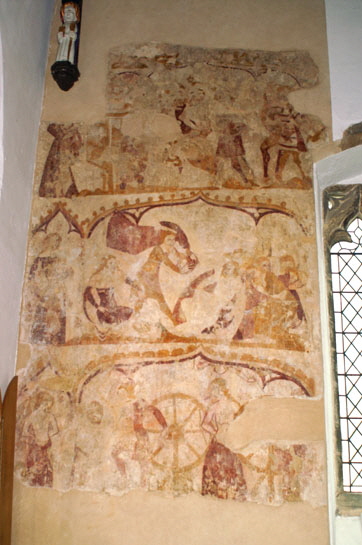

Left: One of the less obvious of the many “wow factors” in Castor Church is this pre-reformation stone altar table (“mensa”) in the lady chapel. It lay outside the priest’s door for centuries before being restored to this place of dignity. Note the Red Admiral butterfly that chose to add a touch of natural spirituality to my photograph! Right: Here, on the other hand, is a very obvious wow factor: the beautifully preserved c14 wall painting of the unfortunate St Catherine with perhaps the most recognisable of all saintly icons - her wheel. The c4 Emperor Maximinus took exception to her ability to convert even his Empress to Christianity and attempted to execute her by “breaking” her on a wheel set with knives. The wheel apparently broke first so Maximinus resorted successfully to the tried-and-tested technique of beheading. Milk allegedly poured from her neck rather than blood.. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

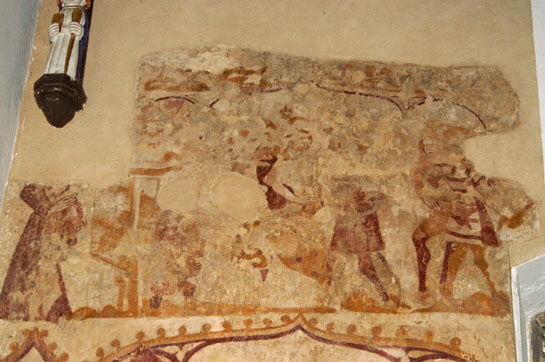

Left: The St Catherine painting in its entirety. In the top panel she converts some of Maximinius’s philosophers. In the second the unfortunate philosophers are themselves executed. It was not a good time to be a Christian, it seems! Centre: The angel roof of about 1450. Right: The magnificent Norman tower. It is a riot of bifora, blind arcading and corbel tables. If there is a finer Norman tower on an English parish church I have not seen it. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Further detail from the wall painting |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: These kneelers make for a lovely colourful picture of the church. The font is c12 and Norman in style. Needless to say, like almost all such fonts, it was declared surplus to requirements at some stage and on this occasion dumped in the churchyard! It was restored in 1928. Right: One of the church’s greatest treasures: an eighth century carving of St Mark. It was found under the altar rails when they were removed and is from the original shrine of St Kyneburgha. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A “Capital Appreciation” |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I have decided not to try to say where each of these capital carvings are located: you can find them easily enough if you visit! Left: One of several Green Man images. Centre: A man trying either to fight or to soothe some rather ferocious creature with the most evil-looking teeth. Right: Apparently a bull grazing. The legs are actually quite well drawn. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The most famous of Castor’s capitals. It is thought likely that the distressed figure on the left is Kyneburgha herself and the two figures to her right are fighting. The ugly character on the right is clearly the villain of the piece and is thought to have had designs on her maidenly honour. Right: A “Cat mask” device. To it’s right is a Green Man. To the left a very perky bird with a long beak. |

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: On the north-east capitals of the tower is a boar who has managed to slice a hound in half. The hapless animal’s forequarters lie on the ground while his rear end is on the end of the boar’s tusk! To the left a hunter with a spear in hand watches on. Right: A ribbon-like serpent. |

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Left: I can’t quite make out what this winged gryphon, or dragon is doing. Up to no good, I imagine. Right: Two very typical Norman stylised designs with yet another Green Man-like image. |

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This magnificent carving of Christ-in-Majesty surrounded by Sun and Moon is sited above the c14 porch and is probably Anglo-Saxon. It has been moved from elsewhere in the church and its shape suggests it was a tympanum. Right: Right: Looking across nave to the south door. |

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

First and Second Left: Two mediaeval roof carvings from the chancel - one a lute player. Third and Fourth Left: Two much more recent carving s from the refurbished nave roof. Far Right: The church from the east end. From this angle the tower looks oversized compared with the church’s width. The east wind is huge and unstained. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|