|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

If you think vaguely that you have heard of Cottesmore before that is probably because its RAF base was once known for its Harrier jump jets. Here we see it as the home of “my” mason, Simon Cottesmore. More of him and his possible mentor, John Oakham, anon. You would have to say that Cottesmore Church has a utilitarian look to it at first site, although as so often is the case its interior is more impressive than its exterior. It is, like many of the churches in my Mooning Men Group study, very substantial. Its appearance is marred by the lack of the usual parapets to clerestory and aisles - usually battlemented - that were normally part of the stock-in-trade of Mooning Men Group. The lead roof is simply wrapped over the edges of the aisles. There is a plain parapet to the chancel but there is a vaguely unfinished look to most of the church. We must exclude the west tower from these observations. This is a late thirteenth/early fourteenth century creation in the Decorated style with a broach spire and a look of great permanence. It is a feature much favoured in the small county of Rutland (I like to call them “Rutland Bruisers”) and can be seen to good effect at Ryhall and Ketton, to name but two more. On this, of, course we would not expect any parapets as the spire is a model of self-drainage! Nevertheless, as we shall see, it has a basic cornice frieze. You might think this is the oldest part of the church but the south doorway is Norman although it has been moved - as is so often the case - from its former position in the nave wall to the later south aisle. How much of the fabric of the church is also Norman is unclear but the doorway is the only obvious evidence of the church’s age. The chancel was extended probably at the same time as the tower was built and is conspicuously long. Pevsner is of the view that the aisles were added in the early fourteenth century. This is hard to verify although there is a single Decorated style window east of the porch that gives a little credence to that. On the other hand, other aisle windows are in Perpendicular style, as is the clerestory. More of that when we discuss this church’s relationship with the Mooning Men Group masons. Within the church is light and airy. The windows and clerestory do a good job. The real treasure of the church is its unusual and very early font. The square base is clearly Norman at the latest and Pevsner puts that at about AD1200 without explaining why. It is crudely carved with a crucifixion scene and a bishop on two of the sides. The other two have rosettes that Pevsner suggests were re-cut. At each of its four corners are human heads, a fairly common style especially far away in the West Country but also seen in Rutland at Greetham. This was very clearly the original font upon which a mass-produced octagonal bowl has since been placed, so that the Norman font is now the base! Pevsner’s dating may depend upon the wavy profile of the blind arches surrounding the two historiated panels but I do not find that very convincing. It is surely contemporary with the south doorway in any event. |

|

Cottesmore Church and the Mooning Men Group |

|

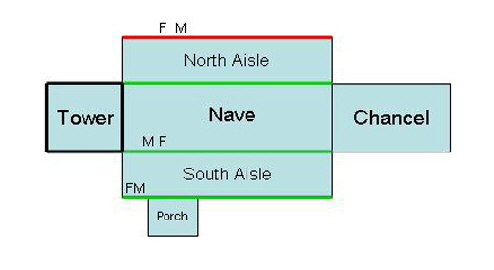

If you have arrived at this page directly then this section is not going to mean much to you. See about the Mooning Men Group of masons by clicking here. Both aisles and all of the clerestory have sculpted cornice friezes throughout. The chancel has none. These friezes are consistent in their rather unsophisticated style. Cottesmore’s was one of the first church friezes I found in Rutland and I christened the man who carved it “Simon Cottesmore”. The style is an exact match to a frieze at Buckminster Church near Grantham. The distinctive “batwinged lion” Simon carved at Cottesmore is replicated both there and at Hungarton in Leicestershire. If Cottesmore is the church with the biggest stable of mooner and flea carvings - three of each with only the north clerestory missing out. On the south aisle here a mooner sits right next to a flea carving. This is precisely the configuration we see on the south clerestory of Whissendine only eight miles away and it cannot reasonably be argued away as coincidence. It was one of the earliest indications that these churches with mooning men carvings have a more complex tale to tell. If you have been following the MMG narrative you will know that I discovered the unmistakable flea carvings as far away as Swineshead and Brant Broughton in Lincolnshire as well as at several churches not far from Cottesmore. Yet the cornice frieze sculptures at Whissendine, not to mention many of the others, bear little obvious resemblance to those at Cottesmore. Again, I have hypothesised elsewhere that the mooning man was the trademark of a peripatetic group of masons with probably a single contractor in charge and that the flea was a trademark of two masons: Simon and the much more highly-skilled “John Oakham”. John was probably Simon’s mentor or trainee. For the much fuller narrative you will need to read the pages that precede this one. The cornice friezes were not commissioned as a separate project. Even if there was not evidence of a peripatetic group of masons it seems inconceivable that a church would go to the expense of cornice friezes - and not very good ones - for their own sake. The Mooning Men Group’s main raison d’etre was to do with building clerestories and expanding aisles and with those, the leading of roofs. Again, it is essential to read the other pages of this narrative to understand that. Those were the activities that surely gave the opportunity for sculpting at Cottesmore. Yet, there are items of the MMG’s normal menu of work that Cottesmore did not buy, it seems. Most conspicuously, they did not commission even plain parapets - and battlements were the norm - on the new clerestory and their changed aisles, to the obvious detriment of the appearance of the church. I will show that they almost certainly did pay the enormous cost of leading the roofs - probably approaching six figures in today’s terms. We might surmise that the parish was financially exhausted - I have shown elsewhere that parapets were themselves not a cheap adornment, taking up to a year to install. With the lack of parapets came a lack of gargoyles. Even today, Cottesmore Church relies - apart from on the chancel - upon gravity to take the rainwater straight off the roofs to cascade to the ground below! Hood moulds protect the windows from rain damage but there are only one or two label stops. All in all, Cottesmore is a little curious in having extensive sculpted friezes but little other decorative adornment. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

Pevsner would tell you that my dating - very late fourteenth or early fifteenth century - of this decoration is wrong. Pevsner, as I have remarked many times, took little interest in decoration that he would certainly describe in his inimitable way as “barbarous”. He says “The clerestory is Dec, an early date. It has a frieze with ballflower and other motifs”. It is a brave man that challenges the (deceased) Pevsner but I am going to have to, I am afraid. Pevsner put a great deal of store on ballflower. He regarded it as an infallible motif of the Decorated style. That is largely true. Many churches have acres of the stuff and that is very useful for dating. Ballflower, however, did not just disappear once Perpendicular style became all the rage. In the pictures above you can see fair amount of ballflower. It is hardly surprising if Simon (not the most talented of carvers) and John put in a few stock examples to move things along a bit more quickly. This, however, is decidedly not a ballflower frieze. To see what a real ballflower frieze is like see Langham. That being the case, why would the clerestory be described as “Decorated”? Its windows are in fact in Perpendicular style. True, we see one Decorated window in the south aisle next to the porch. This suggests a fourteenth century aisle. Careful examination, however, of the photograph above shows extra courses of masonry have been inserted at the top of the wall. This aisle has had its roofline changed - and its roof leaded - and that is exactly the opportunity that the MMG exploited again and again. The killer fact is that the friezes - especially on the north side - have lots of goffered caul headdresses. That is a much stronger guide to dating than ballflower. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Various images from the Cottesmore friezes. The “batwing lion” (top left) is Simon Cottesmore’s calling card, seen also at Buckminster and Hungarton. There are three mooners and three fleas, including a flea and mooner juxtaposed (above left) as they are at Whissendine (above right). There are goffered caul headdresses (middle row right). There is a nice green man with very distinctive oak leaves - again Buckminster has a near-replica. Green men on the outsides of churches are not nearly as common as they are inside |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Many of the carvings here have an eye formation seen elsewhere only at Buckminster and Hungarton. The eyeballs are sculpted to fit into hollow sockets. With the batwing lions that they also share, this is sure fire evidence of a single sculptor. There are, however, other styles of eye. One has simple drilled holes and another has oval eyeballs that are not contained within hollowed sockets. These have the curious effect of making the faces appear blind (above, bottom row, left). |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Cottesmore the Church |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

St Nicholas is certainly an imposing church. In truth, however, it does not stand out from the great mass of thousands of other largely high gothic churches in the country, nor even amongst its peers in Rutland. The Victoria mania for scraping away the plaster from the walls did no favours for this church. Its best treasure is the peculiar font I described above. Its Norman south doorway is certainly of interest but pales alongside those of nearby Egleton and Essendine. Nevertheless, this is a perfectly fine if rather mundane building. Mundane, that is if you don’t look those carved friezes! Of great interest within the MMG narrative, however, are the carved faces on the spandrels of the south arcade. Three of these have black lead eyes. That tends to confirm the already high likelihood that leading the roofs was one of the main activities carried out here by the MMG. Indeed, in a church that has no rainwater drainage system this would be the only occasion for a plumber to be on site apart from that of making lead fittings for glazing. One of these heads wears a hat with three crosses. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the east end. This is a church that pursued light with some success, and doubtless at considerable expense! The large windows are complemented by the exceptionally open arcades and chancel arch. Both the north and the south aisles have octagonal columns. A Decorated style window on the south aisle suggests a mid-fourteenth century dating for its construction This style of column, however, had much longer currency. The aisles have Perpendicular style windows as well as Decorated ones so there has been quite a lot of tinkering down the centuries. Examination of the west end (right) shows the steep pre-clerestory roof profile. If the arches we see were the originals it would imply that they reached right to the top of the original nave roof which is inconceivable. It is clear the arches were heightened when the clerestory was built and this neatly explains why we see carvings in the spandrels that used black lead for eyes. Right: The view to the west. It is marred visually by the intrusion of the north wall of the tower into the nave space, thus spoiling the symmetry of the church and the line of the north arcade, and somewhat overpowering the otherwise handsome tower arch. I am struggling to think of another church that has an interior clock, by the way. It is behind the congregation. The mediaeval clergy would have approved of that. Don’t want the parishioners clock-watching during the sermon, do we? Note also in passing, the use of loose chairs. I do not know what was here before. If it was mediaeval benches I would deplore an act of vandalism. If, as is much more likely, they replaced bum-numbing utilitarian post-Reformation benches then I would have to applaud it as progress. I can’t see much merit in torturing dwindling congregations unless you are of the hair-shirt denominations of Christianity. And how can you use the church for any more community-based activities if the whole place is a sea of uncomfortable fixed seating? |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The chancel. The east window in its present form is fifteenth century altered from the thirteenth, Interestingly the cusping of the panels below the transom has been subsequently removed. One wonders why? Right: Like many churches close to military installations, Cottesmore dedicates a chapel to its nearby air base. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Three Pictures Left: Spandrel carvings in the south arcade with black lead eyes. The figure on the left is presumably a priest. Representations of faces with “full set” of beard and moustache are fairly unusual so I strongly suspect that this is an image of the priest of the day. Right: A lifebuoy from HMS Cottesmore. Somewhat surprisingly (this is a small village in England’s smallest county!) there have been three HMS Cottesmores launched in 1917, 1940 and 1982. This last was a mine countermeasures vessel that was briefly commanded by His Royal Randiness Andrew, Duke of York in 1993-4. This artefact was from that ship. The itself ship was sold to the Lithuanian Navy (who knew they had one?) in 2005 where it still serves. For more information on the various HMS Cottesmores the best source I found, bizarrely, was on the website of the local private school! https://www.cottesmoreschool.com/About/HMS-Cottesmore/ |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The Norman south door, re-positioned from the original nave wall. Note that some replacement of stones was necessary and some later mason’s grasp of geometry was somewhat deficient.. Centre: The strange font. The top is a bit of uninspired gothic style industrial church furnishing. It takes first prize in the “Budget Fonts” category every year. The base, however, was obviously the original Norman font and altogether more interesting. In a variation of a familiar tale of Norman fonts being defenestrated by later generations of “more sophisticated” worshippers to be replaced by something tasteless but “modern,” this one was found being used as a horse mounting step at nearby Cottesmore Hall. That at least is one up from use as a cattle trough, the fate of many of its contemporaries. English history, eh? Stranger than fiction. Right: The church likes to use the area west of the south porch to store its mediaeval artefacts. Joking apart, the rectangular window is a bit of an oddity. Rectangular implies late mediaeval and the style is palpably Perpendicular. Yet the entire surround is picked out with ballflower carvings - you know, that design that Pevsner regards as an infallible guide to the Decorated style. Cheap shots at Pevsner aside (it’s lucky for me he is dead) this is an odd little anachronism. Note just visible to the left of the buttress, Simon Cottesmore’s trademark batwinged lion (see also above) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Norman font defies accurate dating. Pevsner says around 1200 and I imagine his only rationale for that was the non-round profile of the arches surrounding the sculpted designs. That seems a bit thin to me and it looks earlier. It is, however, surely post-Conquest even though the crudeness of the carving, especially the crucifixion scene (left) tempts one to think Anglo-Saxon. Christ’s agony is something that the early sculptors shrank from portraying too graphically. The heads at each corner, however, are a very Norman feature. Right: A bishop with his crozier and his right had raised in benediction. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: One of two font panels that have a simple foliate design. Pevsner says that these carvings are later, implying that they originally were either blank or have since been refaced and re-carved. I can see no trace of the latter. I do suspect that they were originally blank. Right: Cottesmore’s “Rutland Bruiser” is , like Rutland’s other examples, thirteenth or early fourteenth century. It is a broach spire - a design that allows a tower that is square in plan to elegantly produce an octagonal spire. This one, I think, is relatively late. The bell stage (bottom of picture) has cusping at the head of its bifora. It is then in early Decorated style and should be compared with the earlier version at nearby Ketton that has Early English lancet style bell openings. It is fascinating to see how this iconic tower design (which is not, of course, confined to Rutland) adapted to changing architectural thinking. Nearby Whissendine has a tower that looks to be of the same vintage but whose design is more sophisticated, reflecting the wealth of Sempringham Abbey that had acquired the church. It, however, has no spire. One of the advantages of broach spires is that they allow water to run straight off their surfaces onto the heads of the passers by! No leading was needed, nor gargoyles nor parapets. Umbrellas compulsory. We do see a frieze here, however, as indeed we do on the broach spires at Anwick and Ewerby in Lincolnshire’s Sleaford Cluster. It is difficult to see why a frieze would be added to a broach spire after it was built. I can see no obvious similarities with the sculptural style of the MMG masons. I believe that this frieze does indeed date from the tower’s building and was not, therefore, carved by the MMG maybe a century later. |

|

Simon Cottesmore and John Oakham |

|

I am painfully conscious that many people will arrive at this page not having navigated the many pages of narrative that explain what the “Mooning Men Group” (MMG) is and who Simon Cottesmore and John Oakham were. They were two of five masons I name on these pages as being part of the “Mooning Men Group” of peripatetic stonemasons that had - believe it or not - a mooning man as its trademark carving on a whole group of churches in this area of the East Midlands. Simon’s carving style is the crudest of the five masons and is obvious only at Cottesmore, Buckminster and Hungarton. John Oakham, on the other hand, was visible at many other churches as far as Boston on Lincolnshire’s east coast. At Brant Broughton his work was magnificent. At Oakham he was madly prolific. His oeuvre varied wildly in both subject matter and quality. One of the mysteries of the MMG was the appearance of the so-called (by me!) flea carving, of which there are are a perplexing three examples at Cottesmore. This is a motif - as I explain elsewhere - that is clearly associated with John Oakham. Yet we also see it also at Cottesmore, Hungarton and Buckminster where Simon Cottesmore carved in a quite different style to John. |

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||