|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

Dedication : St Andrew Simon Jenkins: * Principal Features : Imposing Gothic Church; Mooning Men Group Sculpture |

|||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

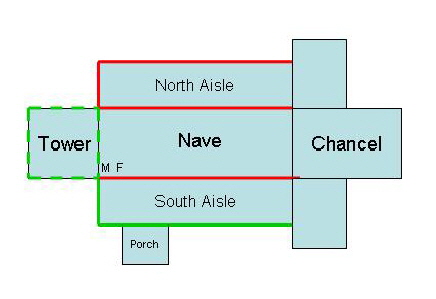

They did, however, surely build the clerestory and put in the new windows on the aisles. They also added the battlements that adorn the clerestory and both aisles. These battlements are of an expensive-looking double-chamfered style that are also seen at other MMG locations such as Langham. And, of course, they added the cornice frieze and sculpted a frieze under each of these eaves. It is probable that the group also leaded the roofs. The chancel and the transepts, however, are curiously plain. This may well be the result of the 1865-70 restoration of the chancel, at which point it had been “in a ruinous state”. That John Oakham was the main sculptor here is certain. It bears many of his hallmark “cow-lion” sculptures. The south clerestory frieze was given particular attention. Its carvings are imaginative and light-hearted. The south aisle, on the other hand, is much more conservative and is similar to those at nearby Cottesmore. All of the south side carvings are in fine condition. This contrasts with the decrepit nature of the south side. Here few of the sculptures survive, although there are enough to show us that John and Simon were the sculptors. These losses are presumably the result of the general deterioration of the fabric and the consequent Victorian restoration. The north side presents a couple of sculptural puzzles. The buttress at the angle of the west end of the south aisle sports carvings of a head and of a lion couchant. These do not look to be the work of John Oakham at all and more over the head has he black lead eyes that John never used. Was Ralf of Ryhall part of the team here? This is not implausible when you consider that they were clearly part of the buttress’s construction: they were not a “finishing off” job in the way that battlements and the cornices were likely to have been. Another little mystery is an “orphaned” dog carving on the north aisle that, again, looks more like Ralf’s than John’s work. Frustratingly, the extensive loss of sculptures prevents us from being more definitive. |

|

||

|

Sections of the south aisle and clerestory friezes. The mooner and flea can be seen at the extreme left of the clerestory. The aisle frieze, probably carved by a combination of John and Simon Cottesmore is much less flamboyant than the clerestory that was probably carved entirely by the more talented John. |

||

|

|

|

Top: Section of the south clerestory frieze. Bottom: The less flamboyant south aisle. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The gargoyles here are often damaged. However, this is one of several MMG churches where Lateral Projecting Gargoyles were provided in abundance, clearly an MMG “thing”. There is a great deal of damage to them - some of it seemingly wanton. I am afraid that later generations happily hacked the heads off gargoyles to accommodate new down pipes. Some are of particular interest. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

It is a little unfair to characterise a fine church only by the external sculpture that is seemingly invisible to most people. In Whissendine churchyard I encountered a church warden if he knew about “his” moon. Reply: “no and I’m pretty sure the vicar doesn’t either”! |

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Left: The church looking towards the east end. Pevsner deplored the extreme scraping of the plaster carried out by the Victorians. The chancel was completely rebuilt by the Victorians from a state of near-dereliction. The Lady Chapel on the right was created only in 1892 a very neo-Catholic trope of the time. It has a screen that removed from St John’s College Cambridge where the Gilbert Scott was carrying out renovations. He was working at Whissendine too and so he “appropriated” it. Right: Looking to the west. We can see very clearly how the roofline was changed when the clerestory was built by the Mooning Men Group. The tower arch is very fine and imposing leading to the early fourteenth century west tower. A five bay nave is imposing indeed for a church serving a small community. The westernmost bay was added when the tower was built. Sempringham Abbey who had acquired the church (a far from unusual occurrence that often left the parish church without a full time priest and with most of its tithes being appropriated - that word again - by the mother house) clearly intended to impress. |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

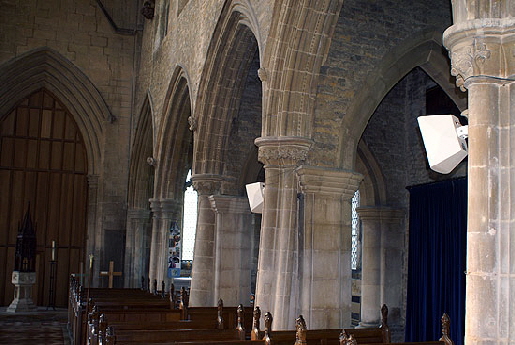

Left: The Victorian chancel. It is certainly an ambitious design with wood panelling all around and a stone reredos by Kempe, better known for his stained glass. Right: The pillars of the north aisle. Pevsner clearly found them difficult to date. Jenkins found them “a delight” and “apparently Decorated but with a wilful variety of capitals”. I suspect that the mediaeval masons were much less wedded to the style of the day than modern commentators like to assume especially in the later mediaeval (Decorated and Perpendicular) period . Note the heavy outward leaning. The arch to the right is clearly a desperate attempt to avoid disaster. Too often the ambitions of parishes and acquisitive monasteries outran the ability of a church’s foundations to support them. Like so many, this church had seen its aisles widened and a clerestory and massive west tower added. Let us not forget, either, the massive weight of leaded roofs and their supporting timberwork. Who knew what sort of footings the earlier generations of masons had put in? This lean is undoubtedly why the north clerestory and north aisle have lost most of their original cornices. I imagine the north side had needed quite a lot of shoring up over the centuries. |

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Two of Jenkin’s “wilful” capitals. Decorated style they certainly look. But how much store can we put on our modern dating of columns and capitals? Especially when we know that parishes and patrons sometimes liked to emulate neighbouring churches. |

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Left and Right: Probably the best feature of the whole church is its impressive clerestory roof corbels. Kings sit within niches supported by grotesque figures. Jenkins rightly points out that Roundhead soldiers loved to use kings as target practice so these are lucky survivals indeed. What is most interesting is that they obviously date from the installation of the clerestory by the MMG. So craftsmen from that group carved them. But here’s another interesting thing. They are not made of stone, as everyone implies: they are made of wood! If you don’t believe me take a look at the pictures below. You can almost see the heads of the worms coming out of the holes! It is pretty impressive work, I think you will agree, These corbels beg a question that I have long mused over. You would not expect to see a mason constructing a roof. That would require all manner of knowledge of the properties of wood that a mason would be unlikely to be aware of. There would be carpenters on site to build roofs, that’s for sure. But I have often wondered if a mason might turn his hand to decorative timber carving.... |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Timber corbels. Many, including the three on the left are obviously village band figures. The rest seem to be showing what are probably monks in a variety of attitudes and presumably representing those of Sempringham Abbey. As with many misericords - themselves by definition commissioned by monasteries - these corbels poke mild fun at the monks and nuns. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Does he have earache? Is he hard of hearing? Does he put his finger in his hear so he can sing harmonies? Is he a folksinger...? Centre: This one has nodded off. Right: whereas this one is bright-eyed and bushy-tailed and going about his or her devotions. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The aisle roofs has the stone corbels you might expect. Right: The roof timbers too have some grotesque carvings. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The west end of the south aisle. It has a gabled profile which is fairly unusual and, one surmises, both more expensive and more difficult to drain. Right: The south aisle and porch. The windows are Perpendicular but retain a circular head that is more reminiscent of the Decorated style. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The west tower is the finest part of the structure. It is one hundred feet high and was constructed in the early fourteenth century. The bell stage is particularly impressive. The very topmost stage looks somewhat later. Four hefty pinnacles were placed at the corners, a rather odd arched parapet was added, an oddity we see repeated at Oakham just down the road. Right Upper: The parapet of the tower has a frieze of its own. Probably because the tower is so high, the frieze is conspicuous by its lack of quality. Like its counterparts at Oakham and Cottesmore it comprises no more than a monotonous course of crudely-carved faces. Moreover. it has suffered very badly from weathering. I suspect that his frieze it was carved by the MMG, possibly by Simon Cottesmore. The dating is supported by one of the gargoyles (right lower) which very clearly is from the same stable as those on the south clerestory - see above. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

More External Carvings |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Pictures Above: A closer look at some of the carvings on the south clerestory - the most interesting section of frieze. Note particularly the bone-shaker (bottom row, second left) that has a goffered caul headdress. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Very little of the northern friezes remain but here are three examples including (right) a rather half-hearted green man. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||