|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

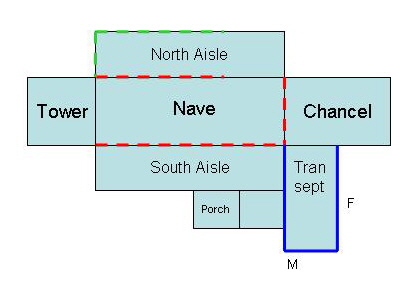

Langham is a very grand church indeed. This is the more remarkable as it is less than two miles from Oakham, Rutland’s county town, which is also a very grand church indeed. As we will see, although this is a church where the Mooning Men Group left their inimitable mark, it is also my biggest problem in deciding who were the sculptors. The west tower here is yet another Rutland Bruiser of the late thirteenth/early fourteenth centuries. It has four rather low-profile “squinches” that allow the square tower to have an octagonal spire. It is, I think, no coincidence that the area has so many of these mighty structures - see others at Ketton, Whissendine, Ryhall and Cottesmore. Fashion will have played a part, of course, but these are mighty structures and institutional knowledge of the building methods amongst the local stonemasons was surely even more crucial. Along with the chancel, this is the oldest part of the church. The aisles were also there at that time but these were remodelled later in the fourteenth century at which time the arcades were altered to what we see today. Also remodelled were the north and south transepts. The north transept was demolished in the nineteenth century. The fifteenth century saw the addition of the very lofty clerestory and it surely the Mooning Men Group that carried out this work. The south face of the transept was raised and a magnificent Perpendicular style window inserted. Gargoyles were installed and we must presume that the MMG also leaded the roof. Whther there was any reprofiling of the aisles we cannot tell. What is certain that the whole church was given battlements including the chancel that was apparently otherwise untouched. The battlements are of the sophisticated - and we must presume expensive - double chamfered variety seen also at Oakham and Whissendine. Windows were replaced in the more modern Perpendicular style part on the north aisle and west of the porch on the south aisle. All of this leads to the church having a most impressive view from the south, further enhanced by the unusually beautiful churchyard. It is worth looking at Cottesmore Church a few miles away emphasise the difference battlements can make to the appearance of the church. To us battlements perhaps appear as something of a cliche but we should not underestimate the tastes of our mediaeval predecessors who would not have had the means to go charging around the countryside to realise that so many churches were doing exactly the same thing. Even if they had, it would have been unlikely to have made a difference. They knew what worked and with an understanding of the cost of such things - I suspect at Langham it took between eighteen months and two years to install the extensive parapets - we can surmise that they were a matter of great pride to the parish and patrons. |

|

Langham Church and the Mooning Men Group |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

It is clear that Langham was a major and prestigious project for the MMG. Their presence is announced by a mooner carving on the south side of the remodelled south transept. Here too we find a flea carving. This was the personal trademark of the mason I call John Oakham as opposed the corporate trademark of the mooning man. Yet there is no clear evidence that John was here at all. And one mason who carved on that transept frieze was Lawrence of Leicester. Lawrence carved no other flea motifs. Although he clearly carved on the south transept frieze some of the sculptures. - like two fighting dogs - are unlike anything he left elsewhere. The most likely answer to the flea carving conundrum is that John carved on this frieze as well as Lawrence. The more discernible north aisle frieze is a fairly close match to some of the carvings at Cottesmore but it is difficult to be certain. As for the clerestory, it looks too sophisticated and varied for either Lawrence or Simon so I would plump for John Oakham - with reservations. We can never rule out a mason having a short association with the MMG and then moving on. The clerestory has a frieze throughout its length, including the gabled east end. Some lengths of cornice with their carvings have been lost and what remains is badly weathered. It is unusual for having quite an array of animal carvings but sadly little of it has avoided considerable weathering and so we cannot enjoy them as we would wish to. In between these highlights there is much that it mediocre to the extent that the masons have not been too shy to insert the occasional ballflower and other devices that are little more imaginative. It is not possible to attribute any of it to any individual mason. On the south side we see a the surprising survival of a badly weathered single carving with black eyes. There is also a goffered caul headdress on the north side. The demolition of the north transept led to the extension of the south aisle to take up the space. It seems likely that the list clerestory had a cornice frieze of its own, The north aisle carvings have survived rather better, presumably being lower down and less exposed than the clerestory. They are, thus, quite a lot clearer and, it must be said, uninteresting. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The south frieze of the south transept, Frieze all of part by Lawrence of Leicester. Third from the left is the mooner. Note the luxurious “double chamfer” battlementing. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Section of the south aisle frieze, possibly by Simon Cottesmore |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Images from Lawrence of Leicester’s south transept frieze. The drilled eyes are characteristic of this mason. The mooner, flea and goffered caul headdress are all MMG icons. The fighting dogs (top left) are far more likely to have been carved by John Oakham than by Lawrence of Leicester. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

These three rows show some of the more interesting imagery at Langham. Animals and hunting are a theme here with two examples of dogs apparently chasing animals around a corner of the parapet (see top right and bottom left). Weathering makes identification all very had work although there is no mistaking the bunny (top left). Bottom Centre: The only example of a carving with black eyes, located on the north clerestory. That degree of weathering is typical of this exposed side and it surprising the eyes survived. It begs the question of how many other eyes might have been lost. Bottom Row Second Right: A goffered caul headdress is an unsurprising discovery. Bottom Right: There are one or two more animal figures on the north clerestory although they are not as extravagant as those on the south side. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Top: The clerestory frieze round the east end of the nave. It too has animal carvings including what seem to be three monkeys (two of them shown above left). Also unusual at Langham is the provision of two windows, one of them visible here with two label stops. One of these label tops is a maned, tongue-poking lion that appears quite a lot around around the MMG, including at John Oakham’s Denton Church reinforcing the likely John Oakham connection. You can see from the picture that the cornice has been carefully constructed to fit around the window. It is certain that these nave windows are contemporary with the clerestory and its cornice. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Langham the Church |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Attractive as the church is externally, and fine as its proportions are, there is in truth little to stir the blood inside the church. This is the frequent fate of richly-endowed churches that had a tendency to dispense with what was “old-fashioned”. Left: The view to the west. Note the two windows above the chancel arch, a rather unusual arrangement. Those windows are in the same style and obviously contemporary with the clerestory windows. No effort has been spared here to increase the light and the Victorians resisted the temptation to scape off the plaster. The chancel arch and the arcades are as one, products of the fourteenth century rebuilding. The aisles are surprisingly narrow. They too are thought to have been remodelled in the fourteenth century so perhaps the parish and patrons thought better of extending them less than a hundred years later. It is known, however, that were reroofed and and refenestrated when the clrerestory was added. Right: Looking into the south transept. The Y-tracery east windows (left of picture) betrays a date of around 1300. The south window, however, was replaced by a grand Perpendicular window at century later. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking directly into the south transept with its showcase window. Centre: The tower arch is contemporary with the west tower. Its chunky masonry contrasts with the lightness of the arcades and chancel arch. Right: This memorial tablet takes the prize for understatement. 1st Airborne in fact lost eight thousand men who took part in the ill-fated Operation Market Garden and it was disbanded after the few survivors returned to England. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: There are two spandrel carvings, facing each other across the east end of the aisle arcades. That to the north has this familiar goffered caul headdress that seems to date it to the time of the fourteenth century changes. Other Pictures: These are clerestory roof corbels that must also date from the clerestory building. There are not obvious parallels for this style amongst the MMG. Similarities in style and much easier to discern on constrained repetitious sculpture on external cornices than they are where masons had larger canvases on which to let their artistic juices flow. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Only in the south porch does the church show real disorder. Make of this mess what you will! Centre: The east end of the north aisle. You can see very clearly the roofline of the north transept that was demolished in the nineteenth century. Frieze sculptures will have been lost with it. Note the bodge job that was carried out on the parapet. The aisle was extended to replace it. Rather unfortunately from an aesthetic viewpoint it was given a window with an outline consistent with the existing north aisle windows but no tracery which looks a little odd. Right: The next bay of the north aisle with the original fifteenth century window. Note the lack of frieze carvings on this part of the aisle and the badly-weathered and sparse ones on the clerestory. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The noble face of the south side with the south transept prominent. Right: The church from the south east. The chancel and the east face of the transept were built in ironstone with some attractive little courses of limestone. Yet the rest of the church is ashlar-faced limestone. That all seems a little odd, especially as the chancel and the west tower are thought to date from around the same time. Although this face if the transept is of ironstone the other two sides are, again, limestone. This all gives the impression of a church where rebuilding was frequent and the written accounts of its chronology are somewhat unconvincing to my eyes. The chancel itself acquired a rectangular west window that presumably post-dates the rest of the chancel window but we have to take account of a restoration of 1876. What is a little baffling is that its cornice is decorated with ballflower and it does not seem at all likely that this was the work of the MMG. Ballflpwer friezes (as opposed to the occasional example as a filler) were passe by now. The clue here is, I think, in a very slight variation in the merlons (the sticky-up bits!) of the battlements that have an extra decorative groove. This suggests that it was installed during the fourteenth century rebuilding and was left alone by the MMG. In this very picture we can see Lawrence of Leicester’s transept frieze and the clerestory frieze probably of John Oakham. The transept windows are from the fourteenth century. It looks as though the wall were raised when the parapets were installed. |

|

|

This picture serves to contrast the densely-packed ballflower cornices of the south aisle and and the porch with the historiated frieze on the fifteenth century frieze built above it. Again, we are left to ask why ballflower friezes appear below fifteenth century parapets and again the most rational explanation is that they were already in-situ when the battlemented parapets were built. Note the parvise room window over the doorway also has ballflower decoration beneath a square hood mould. This tends to confirm that the balflower pre-dates the erection of the clerestory. The aisle windows match those on the north aisle and surely replaced designs more in keeping with the Decorated style ballflower decoration? I deprecate Pevsner’s anxiety to see even the occasional example of a ballflower carving as being of huge chronological significance but these long courses of the stuff are very definitely of an era some decades before the MMG were here building the clerestory and battlementing the parapets. |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Langham is very hard to “read” within the context of the MMG. The south transept has both a mooner and a flea carving so we can safely affirm that this a church visited by the MMG and that John Oakham was part of the group. That south transept frieze is very definitely mainly by Lawrence of Leicester but one or two standout carvings convinces me that John chipped in and that his is why the flea carving is where it is. The clerestory frieze is equally opaque. The north side we have to write off in terms of positive attribution because of the amount that has been lost. The south side has fared much better but there is still nothing to positively point to one mason versus another. I am inclined to believe that the animal carvings are by John and the rest by Lawrence or even Simon Cottesmore. This is all very sketchy and begs some obvious question: why is there no flea carving on the clerestory? Well, of course, there might well have been one on the near-destroyed north side. Then there is the question of why, against all the odds, a pair of black lead eyes survives there. That is Ralf of Ryhall’s trademark. This is not something that John did as far as we know. Why, also, did John completely abandon his characteristic cow-lion motifs that proliferate at Oakham and Brant Broughton? To sum up then: we know Lawrence of Leicester was here and carved on the south transept. The flea carving tells us that John carved on that transept too and almost certainly elsewhere on the the church - but we can’t be sure where. Ralf of Ryhall might have been here. So might Simon Cottesmore. So too might be masons who were attached to the group temporarily. This is not a precise science unfortunately. |