|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

means that it is not nearly as disproportionate as some. It also has a “broach spire”, again typical of this area, an architectural device whereby a square tower cross-section is translated into an octagonal spire - see picture above!. So far so unexceptional, albeit this is is a finely-proportioned and airy church. Two things, however, are exceptional. One is the super-abundance of monster heads and foliage decorations that adorn this church a foot or two below the roof line. Many churches have these, of course, but Ryhall has them on every wall other than the tower, and it has some interesting label stops (that is, figures at the ends of the window drip moulds) to boot. What is more, many of them are very amusing and probably the work of a single sculptor. We are not seeing here the work of the Normans, so there is not their mix of pagan and Christian symbolism: these seem to be here just for fun! They are not, by the way, corbels which would be immediately below the roofline, nor gargoyles which strictly speaking are rainwater spouts. The Church Guide speculates that some of the figures may be of local worthies “nearly 900 years ago”. In fact, this would not be the case for those on the outside: the aisles were extended in the fifteenth century and any external decoration that pre-dated that would have been lost. More interestingly still, some of the carvings on the south aisle were clearly executed by one of the masons that had done similar work on Oakham all Saints Church where the aisles were, like Ryhall’s, known to have been raised in the early fifteenth century. So it looks like our local worthies were from around 600 rather than 900 years ago! Inside, there are two three-bay arcades. Both date from the thirteenth century and are in Early English style. The north arcade is slightly the earlier. Water leaf capitals are predominant and most of the capitals and piers are circular. There is a fine double-seat sedilia in the chancel with crocketed canopies. In keeping with the exterior, there is a head of some kind at every available intersection in the nave, although they are human rather than grotesque, here we might indeed suspect that some of the heads were of the aforesaid “local worthies”. Sadly, the most imposing figure of St Christopher, occupying his traditional place opposite the south door, has been badly damaged but is still of interest. I said there are two exceptional things in Ryhall Church. The second is the remains of an anchorite cell on the west wall of the north arcade. For more information on anchorites please see the page for Iffley, St Mary the Virgin Church. Ryhall was once the home to St Tibba, the patron saint of falconers. For more information on her see the bottom of this page. The anchorite cell seems to date from the fifteenth century and has long since been demolished. We can still, however, see its roofline, a niche in which presumably would have been a statue of the saint, and a squint that would have allowed the lady to see the high altar. |

|

Ryhall Church and the Mooning men Group of Masons |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ryhall Church is the one where my quest for the Mooning Men Group (MMG) began. If you don’t know what I am talking about then you should read my online account of it all. Suffice to say that carvings on the south side of the church here are clearly by the same man who carved similar grotesques on the north west aisle at nearby Oakham. This discovery led to my discovery of a whole raft of churches with sub-parapet cornice friezes carved by a peripatetic group of masons. It is a matter of commonsense that a church would not commission great quantities of sculptural carving as a one-off job. We need to understand what structural work created the opportunity. In the case of Ryhall that opportunity is very obvious: the replacement of the chancel, the construction of the clerestory and the widening of the aisles in the early fifteenth century. You will need to read more of my “book” to understand why I am so sure of the dating. All of the parapets beneath the aisles and the chancel, as well as the south porch, have sculptural friezes and and are clearly of a piece in terms of the style and probably the sculptor, although we can never be quite sure of that. The roofs have parapets that would have hidden the ugly mediaeval lead from view. It is below those parapets that we find the cornice carving. The clerestory has no frieze. We can’t know why. Most of the MMG churches have one but it is clear that the provision of sculpture was subject to the vagaries of time pressure, the parish budget and the availability of sufficiently skilled masons. Ryhall, as well as having by some distance the best and most interesting friezes of the MMG churches, also has the most interesting array of drip mould end stops (“label stops”) and these appear on the clerestory as well as the aisles and this assure us that the widening of the aisles and the raising of the aisle were part of the same program. Ryhall does not have battlemented parapets that are rather more usual with the MMG but, again, there would have been many factors that could have led to this; not least the fact that battlements were more expensive. Despite its being the wellspring of my Mooning Men Group research Ryhall, ironically, sits on the eastern periphery of the MMG group area. Moreover, even more ironically, it does not have one of the mooner carvings that were the trademark of the group. The mason who carved here was the man I dubbed “Ralf of Ryhall” and it seems that he was not a devotee of the icon. The mooner was, I believe, the trademark of a group working under probably a single contractor-mason, not of any individual mason within the group. This leads me to believe that at Ryhall he was working under a a different contractor and, I believe, probably was doing so at nearby mooner-less Thurlby as well. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The view to the east end. Above the chancel arch are boards proclaiming the Ten Commandments. Right: The view to the west end and the Early English tower arch. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The north arcade (right) is slightly older than the south. Architecturally there is little to differentiate them and this makes for a pleasing symmetry. Note, however, the octagonal capital on one of the northern bays and the slight variations between the water leaf designs on the capitals. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The St Christopher figure on the north arcade has suffered grievously. The Saint has lost his arms and Christ, who would have been on his back, seems to have retained only his legs - presumably a result of the Puritan hatred of “idolatry”. We can still see how imposing this figure would have been. Right: The c15 chancel. Little of Ryhall’s glass is stained, even at the east end, so this is an especially light church. Memorials adorn the walls, but this is not a church taken over by the local “great and the good”: it has always been essentially a village church serving the common people of the parish. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

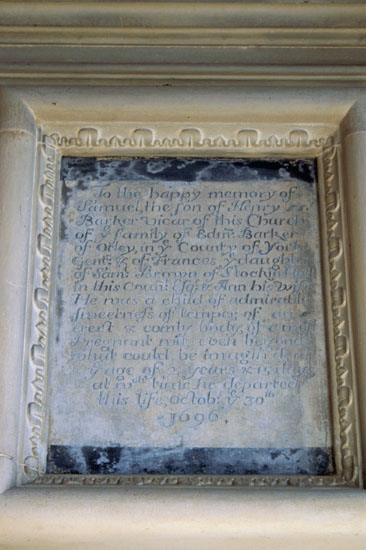

Left: The fine double sedilia with ogee arched canopy and crocket decorations. The right hand arch is rather lopsided! Centre: This memorial on the north side of the chancel is to the memory of the unfortunate Samuel Barker who, the son of the Vicar of the day, who died in 1696 at the tender age of 2 years and 15 days. The memorial leaves us in no doubt that a prodigy had been lost to the world : “... a child of admirable sweetness of temper of an erect and comly (sic) body, of a most pregnant wit, even what could be imagined....” Right: On the west wall of the north aisle, suitably honoured with curtains and flowers, is the squint from what was once the anchorite cell. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Like many mediaeval churches, Ryhall shows just a tantalising glimpse of the paint that would have once adorned the whole church - in this case on the soffit of the chancel arch. Right: The outline of the anchorite cell on the exterior of the north aisle. Note the empty roofline, the niche on the left and the squint on the right. The loss of some of the roofline nearest to the chancel (right) seems to indicate that the cell may have been removed either contemporaneously with or before the widening of the aisles in fifteenth century. This is pure speculation on my part. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The “Wall Art” (for a gallery of the whole frieze click here) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Careful study of the bestiary on Ryhall Church reveals quite distinct groupings. The group above come from the south wall of the chancel. We do see here some fairly recognisable motifs. The bull (top left) is pretty obvious, with possible a crude lion to his right. Top right is a strange figure with a definite owls face but an animal’s body. The owl seems to have something in its mouth. Lower left the human-like figure seems to be - there is no way to put this delicately - scratching his bum! Centre left is what looks very much like a jester, Lower right is hard to make out. Does the figure have spider-like limbs? Is some creature on his head? |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

The figures above are from various parts of the church but, again, some of the styles are distinctive. The chap in the middle of the top row looks for all the world like the very great grandfather of Wallis (as in Gromit!) fame. There are plenty of (rather undistinguished) foliage motifs around the church which have not been worth showing here, and a very few that are neither grotesques nor foliage. Top right is one of those: an eight pointed “star” created by two intertwined squares with concave sides (sorry about the geometrical imprecision!) enclosing a flower. I can find no Christian meaning to this symbol so maybe it’s not a star at all but just a nice pattern. On the middle row, the left hand figure is surely meant to be a bat? To the right we have two musicians playing what looks like an Irish bodhran (to be sure) and a shawm - a popular mediaeval instrument. On the bottom row left a dog-like figure seems to be tucking into the head of a winged creature. On the right - there had to be one! - is a Green Man with unusually human face and spewing forth unusually large leaves. The guy in the middle is just rude! |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Now we come to the cream! These figures are all clearly carved by a single sculptor - the man I call “Ralf of Ryhall - with a liking for winged monsters and they are all in two courses around the west side. Except these “monsters” have a playful look about them. My very favourite is top right which I swear is a female monster trying to look seductive! The figure middle left leers magnificently: I don’t know whether that’s a hand on the left of him, or a leaf. Bottom right appears to me to be a rather cheeky chap. What is quite distinctive about these carvings, apart from commonality of style, is the use of black stones for eyes. Of even greater interest, is that these are quite clearly by the same man who carved similar maned figures on the north west wall of Oakham, All Saints Church. The greatest treasures, in my view, are the two human images at the bottom of the left hand column. They are found on diametrically opposite positions on the south porch. The upper figure holds a masons hammer in his left hand and you can also see a miniature millstone. What he holds in his right hand is not obvious but my surmise is that it is a bread shovel - the long implement used by bakers to place loaves in the back of the oven. This we have three trades represented: mason, miller and baker. The other figure clutches a flaming hammer in his right hand - the tool of the blacksmith. His left hand clutches what appears to be a sheaf of cloth and probably represents the fuller. Thus we haev five village trades represented in two carvings. The faces are very human and it is difficult to believe they are not real people, especially the very distinctive upper figure with moustaches and very strange hair! |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A selection of label stops from the aisle windows. Although many are the conventional, rather stilted faces, these three show an exuberant distaste for convention that sets the carvings on this church apart. In fact, I am not sure there is a single Christian image amongst all of this mayhem. The label stop on the left is clearly by the same man who carved the maned figures elsewhere here and at Oakham. One creature seems to be giving another a piggy-back ride. The middle one may be his work too. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Although Ryhall has no frieze, it does have an entertaining set of label stops. You won’t see pictures of some of these anywhere else. As at many churches the clerestory labels are blocked or partially from view by height of the aisles. Ryhall’s north clerestory is particularly difficult but from our master bedroom window and using a 300 mm lens I was able to get these shots. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Black Eyes |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There are many examples at Ryhall of carvings that have black eyes made of lead. Indeed, Ryhall is the “home” of this peculiarity. They are not unique: there are some at a few other “Mooning Men Group” churches, especially at Lowesby in Leicestershire but outside of this group and this area they are very rare. Such work would have required the presence on site of a plumber - a worker in lead: masons would not handle molten lead - specialised and dangerous work. The plumber’s main work at Ryhall, as elsewhere, was putting lead on the shallower roofs of the extended aisles and n the new clerestory and chancel. He would also have been making gutters and making fitments to secure panes of glass. The black eyes are one of the distinguishing marks of the presence of the MMG, and Ralf of Ryhall and his fellow mason, the “Gargoyle Master”, seem to have been the main users of the device. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Not all of Ryhall’s carvings are outside. Some of the interior ones are also interesting, even if they do somewhat suffer from comparison with the monster gallery outside. These carvings - in the spandrels between the arcade arches - are contemporary with the widened aisles and the clerestory, as the furher use of black eyes would indicate. It is a largely overlooked fact that such work would necessitate the remodelling of the arches even if the columns were themselves left untouched. Centre: Lots of churches have heads of king and queen, and this is Ryhall’s king. It would win few prizes for sculpture! Right: The east window of Ryhall’s Lady Chapel is by the renowned Victorian, Thomas Kempe. Another one can be seen at nearby Wittering, All Saints Church. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

Left: Except for during his earliest days, Kempe always incorporated a trademark wheatsheaf into his windows. This is Ryhall’s. Right: And finally, another grotesque, this time from the interior. |

|

St Tibba |

|

History does not leave us much information about St Tibba, but of her existence there is no doubt whatsoever. The Domesday Book (1086) talks of Ryhall thus : “During the seventh century St Tibba, patron saint of falconers, is said to have lived in a cell on the site where the church now stands”. She is also mentioned in the “Anglo Saxon Chronicles”. We do not even know why she became the Patron Saint of Falconers. The word “Teb”, however, is the Egyptian word for waterfowl and the waterfowlers of Rutland were recorded in seventeenth century being “addicted to her worship”. It seems that the possibility of a pre-Christian association with her patron sainthood led to her being expunged from some historical documents as a result. Whether this association holds water we will probably never know. Nor do we know why the association came to be with falconry in particular, rather than with other forms of hunting. Falconry was not widely practised in Saxon England until AD875, some 200 years after Tibba’s death. We do know that she was a “kinswoman” - probably a cousin - of St Cyneburgha (d.AD680) who is indelibly associated with Castor Church which is dedicated to her. Cyneburgha (or Cyneburh) was a daughter of King Peada of Mercia. She founded the abbey at Castor and was succeeded by her sister, St Cyneswith (or Cyneswide). The two sisters were interred at Castor and their remains were later removed to Medehamstead Abbey - or Peterborough Cathedral as we now know it. We know also that St Tibba’s remains were moved from Ryhall to join those of her cousins in the eleventh century by Abbot Ćelfsige (1006-1042). As we have seen, an anchorite attached herself to Ryhall Church in c15 and we can see the remains of it today. It is perhaps important to remember that this would have been a good 700 years or more after Tibba’s death - so Tibba’s name was an enduring one. Interestingly, there is speculation that she is also commemorated on one of the Romanesque door jambs at Essendine, St Mary Magdalene Church very close to Ryhall. If so, this is a much earlier relic of her life than exists elsewhere and, given that this was originally a Norman church, it might indicate that it was after the Conquest that she became the patron saint. I like to provoke speculation, so here something to think about. The Norman door at Essendine shows some signs of incorporating components from elsewhere. There are at least two parts of the door jamb that may have a hunting theme. Could these stones have been incorporated into Essendine Church from Ryhall’s original stone church after Ryhall was rebuilt in the early twelfth century? Was this a way of preserving some of the imagery of St Tibba that had no place in the modernised Ryhall Church? The association of Ryhall with St Tibba is not lost. There was a St Tibba’s Well - the location of which is now indeterminate - where her Saint’s day of December 16th was commemorated until comparatively recently. There is speculation that it was near Stableford Bridge in the nearly village of Belmesthorpe - that is at St Tibba’s Ford. |

|

and finally.... |

|

It was customary in mediaeval times to celebrate the saint’s days to read passages from their lives and to sing songs and anthems. Below I reproduce in English and Latin the anthem to Saints Cyneburgha, Cyneswith and Tibba. I reproduce verbatim the source as it was given on the internet : “The source for the background information above and the Latin and English texts of the chants comes from the literature accompanying a Compact Disc recording entitled Chant in honour of Anglo Saxon saints. The singing was by a group called Magnificat, directed by Philip Cave and recorded in Durham Cathedral in 1995. (CD ref is CGCD4004). The CD was produced by a firm called Griffin of Church House, St Mary’s Gate, Lancaster LA1 1TD. The music was transcribed from an original manuscript by David Hiley, who also wrote the foreword above. The text was translated by Davis Norwood. Philip Cave is a member of The Tallis Scholars and a layclerk at New College Oxford” |

|

|