|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There are thousands of pre-Reformation churches in England so when you plan a tour in a specific area it hardly makes sense to just turn up and meander around because you will inevitably miss some of the best bits. You also need to ascertain whether churches you really want to visit are open to view. Most of the churches I visit, therefore, are for a reason. In the case of Devon I was quite preoccupied (as I always am) with Norman fonts. I also, however, wanted to see one of the special attractions of many Devon churches: the wooden rood screens. A remarkable number have survived. This is almost certainly due to the relative remoteness of this West Country county from London and other centres of reforming zeal. Devon and its rather cussed neighbour, Cornwall, have a streak of independence in their outlook that persists to this day. They could not safely insulate themselves altogether from the march of religious progress, of course, but it seems they co-operated in the removal of “idolatrous” images of the saints and the removal of rood crosses whilst resisting the demolition of the screens themselves. When you see how lavish and beautiful many were you will understand their reluctance. A characteristic of many West Country churches (but by no means all, of course) is a penchant for relatively open plans at the east end. North and south aisles and their associated chapels more often than not extend the full length of the church so that they are parallel to the chancel. Between the three easternmost cells the separation was usually effected by spacious arches. West Countrymen were, it seems less enamoured of the private little corners (literally as well as metaphorically) that characterise many churches elsewhere in England. This openness lent itself to the idea of extending the rood screen across the entire width of the church in one glorious sweep of gloriously carved and painted woodwork. There are stone screens in Devon - you can see them, for example, at Colyton and the cathedral-like Ottery St Mary but the fashion in Devon was for wood. It doesn’t take a genius to to understand why: the relative abundance of timber, the ability to carve with great intricacy and the avoidance of the high cost of purchasing and transporting stone within this very large county. On this page, then, you will find churches with mediaeval screens. They are a small sample only. They are “shorts” such as I have written on a couple of other counties like Cumbria and Derbyshire and designed to cover a number of places comparatively quickly and succinctly without giving them the “full treatment”. There are many others in Devon of equivalent or greater merit so they are just a “taster” |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Berry Pomeroy : St Mary the Virgin |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

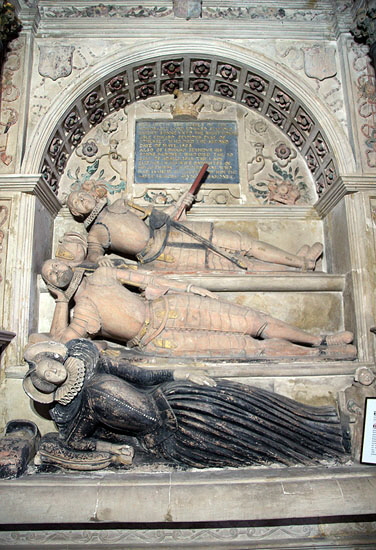

A very good reason for having this church on your itinerary, apart from the church itself, is that it is within a mile of Berry Pomeroy Castle which is well worth a visit. The Church Guide suggests there was a church here from around 1125 but that the present church was it was built over it by Sir Richard Pomeroy (d.1496). Externally its appearance is (like others in Devon) ruined by its grotesquely rendered tower. It is a Perpendicular church to its bootstraps. The arcade is of Beer stone which you can read about in my footnote about Colyton Church. The screen is described by Pevsner as “One of the most perfect in Devon”. It stretches across the entire church and has retained its original cornice and coving as well as its beautiful decoration. The church has associations with the ambitious Seymour family of the Tudor period. It all started, of course, with Jane who became the third wife of Henry VIII. Her brother Thomas was betrothed to Katharine Parr but lost the lady to Henry who made her his sixth wife. After Henry’s death the couple married anyway. Another brother, Edward, was made first Earl of Somerset and after Henry’s death went on to become Lord Protector of England until such time as the child Edward VI came of age. Unpopular with some court factions he was executed in 1552, the warrant from Edward VI possibly having been forged. Sister Elizabeth married Gregory Cromwell, son of the much-maligned Thomas Cromwell and so it goes on. The church has a magnificent three-decked monument to Edward, the son of the Lord Protector, and to his son, another Edward. By the way, the Booker-prize winning novel “Wolf Hall” by Hilary Mantel refers to the ancestral home of the Seymours. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

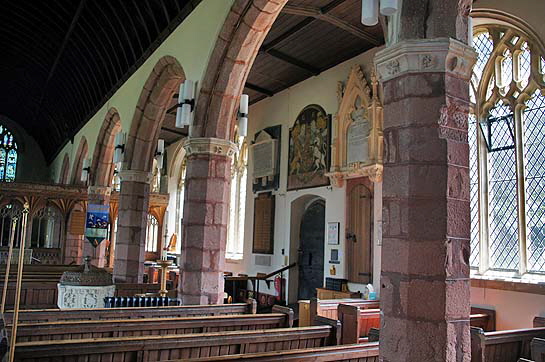

Left: The church from the south west. Get past the ghastly rendering on the tower and this is a pretty little church with the huge acreage of window typical of a Perpendicular church and unusually elaborate battlements. Right: Looking towards the east. The church is airy and spacious. The arcades above their arches of Beer stone are of brick which is not unusual in Devon but would be elsewhere. Across it all is the magnificent rood screen, all forty six feet of it.. Note the reproduction in wood of Perpendicular style window tracery. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The view to the west. Right: Detail of the underside of the screen in the direction of the east window. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Detail of the screen. Look at the delicacy with which plant tendrils have been carved. In the centre is a stylised bird. It looks like a humming bird but that is surely accidental. Right: The carved fleuron that you can also see in the picture above it. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Reformation did not leave the screen unscathed. Here we cam see the heads of the saints have been crudely obliterated by the iconoclasts. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Inside the south porch is this groined ceiling. It contrasts somewhat with the brick facing of the wall behind. In the foreground is the supposed image of Henry VII with whom the carver was evidently unacquainted! At the back, abutting the wall, is the supposed image of Elizabeth of York whose marriage to Henry was a political expedient to unite the Houses of Lancaster and York after Henry’s victory at Bosworth. There are also two Tudor roses and the arms of the Seymour family. The Seymours wanted no doubts about their where their loyalties lay. Centre: The triple decked Seymour monument. showing the two Edwards - son and grandson of Edward Seymour, the erstwhile Lord Protector - and Elizabeth Chapernowne wife of the later of the last Edward. Right Above: A baby in its crib, part of the Seymour memorial. Right Lower: One of the arcade capitals adorned with the name of a benefactor. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ipplepen: St Andrew |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ipplepen is less than five miles from Berry Pomeroy by road. It also is an exclusively Perpendicular style building and it is the third on this site. The Church Guide reckons that the second of these - the Norman building - is “buried within” today’s church but doesn’t say how. I surmise that the arcade walling was once the outside walling of the old church. The north doorway is reckoned to have stone around it that is Norman. Again, I can only surmise when I suggest that it was moved there from elsewhere in the church. If the rendering on the outside of Berry Pomeroy is ill-advised then that at Ipplepen is nothing short of disastrous. All except the chancel has been despoiled in this way. I can only guess that the stonework was being seriously damaged by weathering. The shame of it is that the interior of the church is very pretty indeed. Whereas Berry Pomeroy mixes Beer stone with brick, here we find Beer stone arcades mixed with an attractive red sandstone from Hurdwick Quarry near Tavistock. That’s a good twenty seven miles distant and one wonders why the wealth Seymour family did not wish the same for Berry Pomeroy and used brick instead? Beer stone was also used for the font here. The screen does not have the same riotous colouring that Berry Pomeroy enjoys but it also stretches over the entire width of the church from north to south.. It has a polished timber effect, although it is still elaborately carved. There is a restrained good taste about the whole thing. If “authenticity” is important to you then you will be disappointed to know that the upper parts were restored in 1897. We can’t know to what extent the original was retained but it would be churlish indeed to not enjoy this wonderful work of art. I am sure it is substantially original. The paintings that you see on the lower boards were also restored in 1897 having been defaced during the Reformation. The real standout treasure here, though, is the superb wine-glass pulpit. Like the screen it was blessed by Bishop Lacy in 1430. Its mediaeval colouring has been retained. Its niches had images of the saints but they were defaced and the panels are now black. Remarkably, the original images are starting to show through but not, alas, so we can see them. Given the glorious colours it seems likely that the screen too was originally brightly painted. |

|

|

||||||

|

Left: The church from the south east. Right: Looking east. The screen stretches across the entire width. You can just see to its left the door to the rood screen stair on the north side. Rood screens were not just for show or to separate clergy from congregation (although they did perform that latter function). Some of the mass would have been conducted from that vantage point. Devon clergymen most have been grateful for the local tradition of making very deep screens! Note the darker colour of the restored superstructure as opposed to the Perpendicular tracery below. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

Left: Looking west. The arcade capitals and the font are of white Beer stone which is pleasing counterpoint to the pink “red” sandstone. Right: The underside of the screen with the east window in the background. Interestingly, the parapet work is very different from that at Berry Pomeroy but both screens have a timber representation of fan vaulting. If you look carefully you will notice that the design between the “groins” is pretty much the same as at Berry Pomeroy. Does this indicate the same carpenter being involved in their construction. Or did the restorer copy the one at Berry? |

|||||||

|

|

The pararpet in close-up |

|||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

Above: the magnificent pulpit of 1430. The black panels are where saints have been obliterated. Right Top: A close up of part of the screen. Right Lower: One of the lower panels with restored images of the saints. |

|||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

Left: A stained glass window by Kempe. Centre: The south door with an odd mix of white (Beer?) stone and sandstone. Right: Another view of the screen. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

Left: The south aisle from the west. This is a “busy” church with lots of wall tablets and other wall-filling stuff. Note the door to the right of the south door. This is the door to the parvise room - that is, to the room above the porch. Note the pretty fleuron decorations on the arcade capitals. Right: The font is made of Beer stone and has fleurons very like those on the capitals. |

|

Kentisbeare: St Mary |

|

If this page is Devon Cream then Kentisbeare is perhaps “la creme de la creme”. Kentisbeare is a church that visually attractive within and without. Its screen is magnificent but it has two further items of great interest: a superb west gallery of 1632 and arcade capitals that have carved crests. The fourteenth century west tower has lovely chequerboard patterns created with white Beer stone and what the Church Guide describes as “a rare cinammon-brown variety of the new red sandstone from a quarry at Upton near Cullompton”. As with the other rood screen churches on this page, most of what we see is fifteenth or sixteenth century Perpendicular. As usual, the Church Guide believes there was an Anglo-Saxon church here. They know the consecration date of the present church was 9 December 1259 and that it had nave, chancel, south aisle, north porch, vestry and battlemented west tower. That’s quite an ambitious building if there were nothing here before so we can be pretty sure that there was. A north porch is fairly unusual at a time when belief in the “Devil’s Door” was supposedly widespread. The chancel was rebuilt in the fourteenth century. The fifteenth century screen, again, stretches the full width of the church and is believed to have been carved in the reign of Henry VII by craftsmen from Tavistock Abbey. It is magnificent and said to be unrestored. As the lower panels have no sign of paintwork - see Berry Pomeroy and Ipplepen - we might question whether this is the literal truth. Who cares? The quality of the carving is quite stunning. The west gallery is known as “Anstice’s Gallery” and was given by Anstice Wescombe in 1632. This is very early for such a gallery and its survival is very surprising. Lucky us, because it is every bit as fascinating in its way as the more “immediate” screen. There are paintings of the four Evangelists and a very grand and humanistic King David. Very surprising for the seventeenth century is a series of small grotesque carvings. The juxtaposition of modern (for its time) painting and mediaeval grotesquerie is both bizarre and exciting. Finally, we have carvings on some of the aisle capitals of the Whiting, Clevedon and Pauncefoot families. There is also the arms of the Merchant Venturers Company of which Whiting was a member as well as woolsacks bearing his marks/. Altogether, this church is well worth going out of your way to see. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||

|

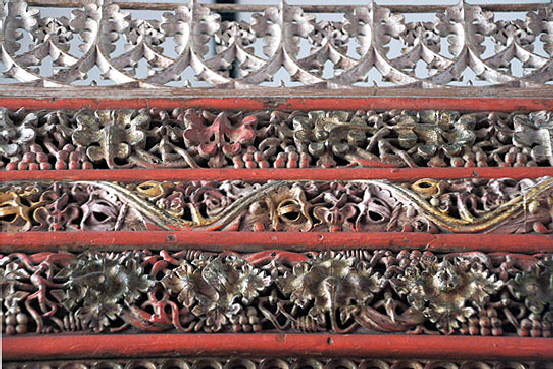

Left: Looking towards the north aisle. Note the “waggon roof” that is almost unique to the West Country. Right: Detail of the decoration on the screen’s cornice. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Two views of the underside of the screen |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left Above and Below: The Whiting wool mark juxtaposed on arcade capitals with the emblems of respectively the Merchant Venturers and the Calais Wool Staple. You can see another (painted) example of the Calais Staple crest at Holme in Nottinghamshire. The Merchant Venturers were based in Bristol through which West Country wool would be exported to the Low Countries. They became instrumental in the development of Bristol. They still exist as a charitable organisation. Right Above and Below: More more family crests on the capitals. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The extraordinary west gallery of 1632. Right: Arms from the lower course of painted decoration on the gallery. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Imagery from the west gallery. Left is the painting of King David with a very child-like crown. Second Left: I thought this was a Red Indian (oh, all right, “Native American” if you must) but actually I think it is an exceedingly ugly woman. I don’t believe the carver lacked the skill to do something more attractive so this is perhaps satirical. The two images on the right are bewildering. These grotesques are not only anachronistic but the designs are reminiscent of a Norman corbel table. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Dunkeswell Church is going to be on nobody’s visiting shortlist except for Norman font anoraks like myself. It’s the fourth building here. This is a very ancient settlement mentioned in Domesday and there was certainly an Anglo-Saxon church here. The first datable building was in 1259 financed by the Cistercian Dunkeswell Abbey nearby. It fell on hard times after the Dissolution and had to be completely rebuilt in the early nineteenth century. Apparently that building was completely botched and another was built in 1868 in faux Early English style. You might have thought that would be the end of this church’s travails, but you would be wrong. During the Second World War there was a US Navy (as opposed to USAF) airbase here, the only one in England. The continual vibration from the engines of the Liberator bombers and Catalina flying boats so weakened the tower that is had to be demolished in 1947 and was replaced in 1955. So to the Norman font and I have to say at this stage we might reasonably assume there was a Norman church to go with it. So were there five churches on this site? Good grief! Norman fonts artistically generally fall into one of three categories: magnificent, mediocre or atrocious. Dunkeswell's, I’m afraid, is mediocre. As a piece of art, that is. This being Dunkeswell, it’s also badly damaged. It is, however, very interesting! How many fonts do you know of with a representation of an elephant? No, me neither. It’s not exactly a brilliant likeness but how many elephants do you reckon the carver had seen? He seems to have a dragon snapping at his hooves while some bloke is taking aim at him with a bow and arrow. Some claim is the earliest representation of an elephant in any English church. The elephant gets one of the longest - perhaps the longest - entry in the mediaeval bestiaries. It might well be there that the absurd notion emerged (beloved of the old comics) that elephants are afraid of mice! They live for three hundred years apparently and mate back to back which must be quite an achievement. The female gives birth in water to protect the offspring against the dragons which are enemies of the elephants. It is generally believed that this is why the imagery appears on this baptismal font. However, the Bestiary also says that the female seduces the male into sex by offering him fruit and it makes a specific (and obvious) parallel to the Adam and Eve story. That theory has my support, for what it’s worth. Another possibility from the Bestiary is that the elephant was considered incapable of adultery. Is he trampling the dragon of sin underfoot? But why the archer taking a potshot at him? Or, let’s be candid, it might be just a load of old tosh out of the head of some mason. In which case, if he’s reading this in some better place (no chuckling - this is a church website, you know) he must be having a right old laugh. What else does the font show? A bishop with a crozier, we can be sure of that. There are a man and a woman - one theory being that it is Lord William de Brivere who founded Dunkeswell Abbey. There's a King. There's a man who some say is in chains although I’m not really sure myself. There’s a defaced figure holding a cross. There’s a panel I can’t make out at all because it is so defaced. Someone else says there’s a “satirical” representation of a physician. I just can’t see that one at all. What fun. The church has a lot of memorabilia associated with the US Navy squadrons here. I am always moved to see these reminders of the sacrifices made by young American boys in a country that wasn’t theirs in a war that many Americans thought wasn’t theirs either. We owe them so much. By the way, one Lt Joseph Kennedy elder brother of JFK was killed while based here. The list of casualties is thought-provoking too. Men died in truck crashes and disease as well as by enemy fire. You might not think this sort of thing is your “bag” but for my money this is history and our English parish churches are still its local repositories. |

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

Left: The church from the south. It’s not very old compared with most of our churches but I think you’ll agree it’s a pretty little place. Right: Looking towards the east end. |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

Top Left: The Norman font. A couple stand hand in hand. This font is crudely executed (although by no means the worst you will see!) but it is an ambitious design. The figures are surrounded by chunky Romanesque arch designs. The cable moulding near the base is a sophisticated and, again, not the worst I’ve seen. Below that is a double course of fish-scale pattern. Lower Left: Obliterated as it is, you can tell that a head in profile presented the carver with an even bigger challenge than a full face! The man is holding a cross so presumably a clergyman of some sort. Top Centre: The elephant. He is trampling a dragon underfoot. Top Right: The archer. He is immediately to the right of the elephant but separated by an archway so it is not clear whether is taking aim at the beast. Given the elephants iconography (see above) that doesn’t seem very likely. Sagittarius is another possibility but there’s not much room below his body and there’s also damage so it is hard to know what’s going on. Above Centre: On the left is a King, his crown clearly visible. To his right is another figure whom some believe to be chained. Above Right: A Bishop holding a crozier. |

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

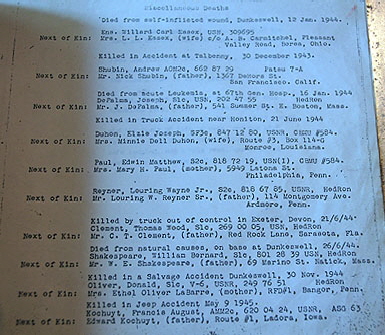

||||||||||||||||

|

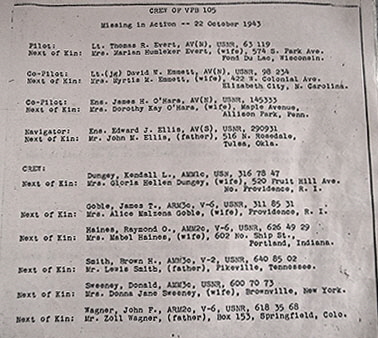

Top Left: A page from the memorial book, showing the crew of a Liberator bomber missing in action in 1943. They were drawn from states throughout the USA. Top Centre: I find this page very poignant. You forget that not all casualties will have been from enemy fire. Three men on this page died in vehicle accidents, another from leukemia and one from “natural causes”. Another died of a “self-inflicted wound”. What drove the poor man to that, one wonders? Top Right: The Stars & Stripes flies in this “little corner of a foreign field that is forever”...the United States. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

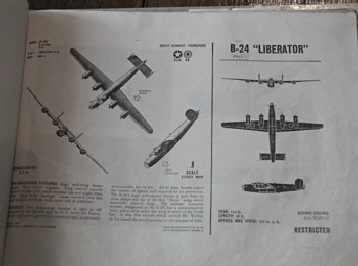

Other Pictures: Various pages from contemporary albums showing Liberator and Catalina aircraft. The Liberators were, of course, long-distance heavy bombers eventually overtaken by the more famous B17 Flying Fortress. The Catalina would, I imagine, have been used on anti-submarine and air-sea rescue activities. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Stoke Canon: St Mary Magdalene |

|

As with Dunkeswell, the church at Stoke Canon (near Exeter) is of little architectural interest. The west tower is fifteenth century in the Perpendicular style, the rest a Victorian building of 1835. The village had been known simply as “Stoke” until in 1148 the manor, which had been endowed to Exeter Cathedral, was used to house the Cathedral’s Canons. Although separate from the parish ministry they doubtless helped out on occasions. Today it is the fine Norman font that will draw the “church crawler” to its doors. Because its decoration is mainly stylised rather than graphic, it is on the face of it, more to be admired for the quality of the carving than for its imagery. The exact opposite, you might feel, of the font at Dunkeswell (above). I believe that to be a misapprehension. Why, you might ask, would a carver go to such lengths to produce geometrical shapes of such sophistication? Clearly, this was a man of some talent. Why not carve something “meaningful”? The answer, I believe, is that this font is of the same corpus of Norman work that the late Mary Curtis Webb spent many years studying. If you peruse these pages extensively you are going to see many references to her book. Indeed, from my homepage you can find links to allow you to read the whole book for yourself. It would be pointless for me to precis it again here, but the crux of it is that she proved conclusively that certain geometric shapes were not, as had always been supposed, merely decorative but that were deeply meaningful in terms of Greek philosophical concepts (especially Plato) and their place in the Christian belief system. Stoke Canon’s font was not mentioned in Mary Webb’s book but I am confident that it would have been had she been aware of it. Her daughter, who actually published Mary’s work, is in agreement with me. Please follow this link: The Late Mary Curtis Webb. Over the last fifty years or so, the notion that the “educated” English monks were responsible for “building” churches has been comprehensively debunked. Our church builders were lay professional stonemasons. Yet there is no conceivable way that the esoteric concepts on display at Stoke Canon and elsewhere would have been known to a common stonemason. Those ideas - not the craftsmanship - must have come from the monasteries. In this case it doesn’t take a genius to work out that the expertise was locally available at Exeter. It is also worth mentioning that all of the fonts displaying this imagery (see Stone, Buckinghamshire, various Northamptonshire fonts and the North West Norfolk School of Fonts) display either excellent or at least good quality craftsmanship. It seems to me that the designs are sufficiently complex to preclude the notion that any old jobbing mason could have done one as a sideline. In the case of Stoke - owned remember by Exeter Cathedral - it is surely the case that the monastery instigated the use of this imagery and then engaged a competent mason? Not only would the common mason not know the concepts but it also seems unlikely that the everyday Norman grandee (normally a mate of William the Conqueror) would either. I also believe that it is ludicrous to suggest that the designs were meant to “educate” the laity. They were surely meant to show off the monastery’s own intellectual prowess - to fellow intellectuals! One last thing. When we visited late on afternoon we found the west end of the church awash with children who had some kind of after-school club there. The part of the church devoted to prayer and ceremony had been drastically reduced. The parish had faced up to the probably irreversible decline in congregation by using some of the space for community purposes. To some it might seem sacrilegious. To us it seemed a laudable attempt to put the church at the centre of the whole community. That is how thing were in mediaeval times when drinking, dancing, storing agricultural produce and all manner of other activities took place within the church. More churches should look to use their buildings like this. It’s just ridiculous to see huge church buildings used sometimes only one Sunday in four while villages seek lottery grants for village halls. Potty. Well done Stoke Canon. Damn, that soapbox just won’t stay in its cupboard, will it....? : |

|

|

||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

The four faces of Stoke Canon font. All of these four designs is slightly different although it’s not immediately obvious. Concentric circles with interlaced loops are representations of Plato’s Cosmos and I believe that these four faces are variations upon this theme. For more information see Stone in Buckinghamshire. That font (it actually came from another Bucks church) was one of the cornerstones of Mary Webb’s work. As you browse the various examples of these motifs, which I hope you will, you will see that they were not slavishly copied. We don’t even know the source book(s) for the designs themselves. If you look at Mary’s book (you can browse it or download it from my site) you will see that appear around Europe but that there doesn’t seem to be any single definitive source for the iconography: no equivalent of the mediaeval Bestiaries, if you like. So the monks directed the carvers but how? Did they have pictures to show or did they just rely on descriptions? From the variations we see around the country it seems likely that the instructions were either vague or variously “interpreted” by the masons, or most likely both. It’s a lot to swallow and there’s plenty of room for scepticism although I am, it must be obvious, a firm believer at least in the fundamental conclusion that the geometric designs are not random. Stoke Canon font, it must be said, is pushing the boundaries of Mary Webb’s work and its inclusion in that corpus is entirely my own idea. You might feel it to be hubris, fantasy or both! |

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

One of the things even I find disconcerting about Mary Webb’s work was her obsessive attention to detail. If she analysed the imagery of a font or tympanum she had an explanation for the tiniest of details. As with the Hampstead Norreys font at Stone and the North West Norfolk School of fonts, Stoke Canon’s font has a good deal more to it than just the geometric designs. The base of the Stoke Canon font has caryatids at each corner holding up a course of cable moulding which in turn shelters a human figure on each face. This is a very sophisticated design indeed with classical antecedents. We can’t see much of these figures (was Stoke Canon’s one of those many Norman fonts that did a spot of service as a cow trough or languished a few centuries in the churchyard?) but we can see that they had meaning. One holds a staff (right bottom), another apparently is giving a benediction (right middle). They might be apostles, they might be saints, they might be clergy. Whatever they are, I think we can agree that this font is not not just meant to be decorative and in my view strengthens my conviction that the font’s main faces had meaning to the intellectual insiders of the Christian Church. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Topsham is a port on the River Exe. It’s a handsome town with plenty of reminders of its heyday as a mercantile and shipping town. We arrived there after a very long morning’s drive and in pouring rain. We were here for one reason: the Norman font. As with Stoke Canon we found little else to interest us in the church which was rebuilt in the eighteen seventies. Pevsner says of its interior: “Spacious if dull, with a variety of Dec windows and a ceiled but traceried chancel roof as the chief ornaments...” The of red sandstone is on the church’s south side but I have to admit it was raining so hard that I didn’t bother to photograph it. So this is all about the font. At Dunkeswell we had a naively-carved specimen with humanist imagery. At Stoke Canon we had fine carving laden with mysterious and obscure imagery. At Topsham we have a magnificent creature carved in the most vibrant way by someone who knew what he was doing. And...er...that’s it. For reasons we can never know the other side is carved with simply striations. It’s as if its creator got called away or died! What is this creature? I’d assumed it was a dragon but he has no wings, although he does seem to have a long tail. He’s not snacking on the tail of another dragon as you see on another superb font at Chaddesley Corbett in Worcestershire. The Bestiary has nothing good to say about dragons so one on its own doesn’t seem very plausible. Pevsner suggests the possibility he has an apple in his mouth. Yeah, right. A herbivore then? I guess we just have to settle for a fantastic beast out of the mason’s own imagination. The only rational explanations are that either the mason never had a chance to complete the picture or that the idea was that baptism overcame the forces of evil as represented by the something like a dragon. All very odd. |

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The church looking east. Apologies for the out of focus picture. Right: A fragment of the mediaeval church.. |