|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

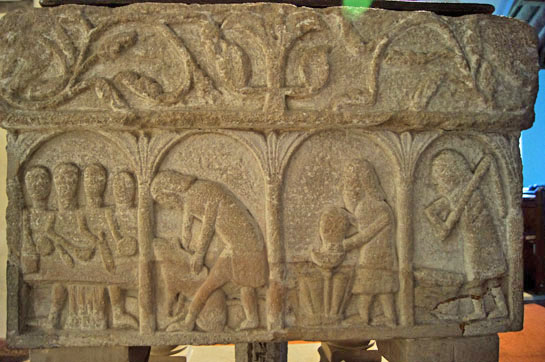

however. This is a rare variation of Norman font that is especially fascinating because it gives an insight into the lives of our eleventh century agricultural forebears. In the mediaeval mind each month was associated with a particular agricultural task. Naturally, these varied slightly between locations because so did the agriculture itself. Do visit my page for Brookland in Kent which has a rare lead font from France also showing the labours of the month but with some months that are different from Deepdale’s. The stone for this font came from the quarry at Barnack in Cambridgeshire which also provided the stone for many churches in the East Midlands and also for both Peterborough and Ely Cathedrals. Like most Norfolk churches, Deepdale is faced in flint which is as prolific locally as stone quarries are rare. This too is one of that traditional explanations for the proliferation of round-towered churches in Norfolk and Suffolk: the difficulty in procuring the massive stone blocks to provide the necessary strength at the corners of a tower of the traditional square plan. There were three major restoration programs here in 1797, at which point the north aisle and the south porch were lost, and in 1855 and 1898. The present south porch was placed here in the 1898 phase. Also the present north aisle. Hence, there has been a lot of chopping and changing here but a lot of the fabric of the south and west walls are probably Saxon. Apart from the font, the real treasure here is a lovely collection of mediaeval glass, much of it, as usual, comprising fragments relocated within more modern window structures. Jury-rig as this may sound, the glass here is lovely and those who find beauty in the garish and mass-produced Victorian glass that pervades many of our churches might like to compare it to the delightful delicacy and art of some of the glass here. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The chancel with its Perpendicular chancel arch. The modern “rood screen” is an interesting and far from ugly piece of innovation. Personally, however, I find the statues to left and right pretty tasteless and strangely alien in an Anglican church. Each to is own, I suppose! Right: The view to the west is much more interesting. We can see the small plain rounded tower arch and the triangular-headed doorway above it. Both of these, and the window in particular, look like nailed-on certainties for Anglo-Saxon work - but are they? See the footnote below. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

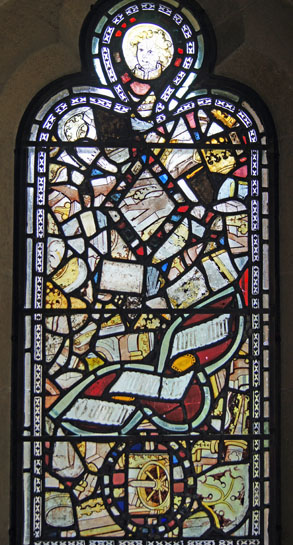

Left: From the outside the tower could be Saxon or Norman. The Church Guide notes that the base of the tower - below the tiled course - is 6” thicker than the rest and this may be Norman work. Centre: The space within the tower is delightful in its simplicity. The window is modern but is set within much larger space. This is explained by the 1797 restoration which put the Norman north doorway here so that the tower was used as a porch for some 50 years or so until it was put back. Right: There are two superb sets of glass in the porch, known as the “sun” and the “moon” because of the figures in the top lights that would have been either side of a crucifixion scene. This window is the Sun.. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Detail from the “sun” window. On the left is a what I take to be either a vicious chariot wheel with a sword blade protruding from the hub - as traditionally used by Boudicca against the Romans. Or perhaps it was a diabolical device for the destruction of martyrs? Right: At the top of the window is a quite cherubic chap with blond curly hair representing the sun. How his mother must have adored him! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

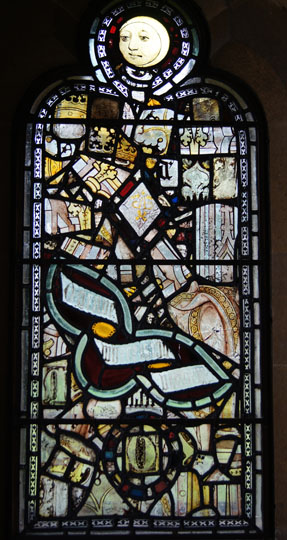

Left: The west window of the north aisle. Centre: In the centre of the north west window we see an emblem of the Trinity. Right: The “moon” window in the porch |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Detail of the west window showing the gorgeous colourful work. Note the three stars in the centre called “rose-en-soleil” (left) - literally roses within the sun. Below these roses (right) is an image of St Ursula, a British saint who was murdered with 1100 other virgins by the Huns on her pilgrimage to Rome via Cologne. They didn’t do things by halves in those days. If you believe this rather unlikely story that was probably written by a Roman chronicler who might just have had a bit on axe to grind! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The moon image is quite exquisite. Just look at the eyes and mouth. Instead of the usual idealised imagery this is a face that could have been modelled by a woman in the village, such is its humanity. Right: Another fragment of glass from Deepdale’s “collection”. It doesn’t have the imagery of some of the other examples, but it shows the vibrancy and delicacy of colour of mediaeval glass |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Labours of the Month Font |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

It is not altogether clear why the Labours of the Month were a popular topic for Norman art. I can think of no examples in England that pre-date or post-date the Norman era. You can see another on these pages on the celebrated lead font at Brookland in Kent. Hardham in Sussex has traces of Labours of the Month wall paintings amongst what is perhaps the finest mediaeval painting scheme in England. The easy explanation is that they were meant to remind the peasants of what they should be doing at various months of the year. Frankly, when you think about it that seems like hogwash. People who lived their whole lives toiling on the land would hardly need education in such matters from the Church. The rhythms of agricultural life would be known collectively not just by individuals and there was certainly a degree of communal labour-sharing. And if a serf should be afflicted by amnesia he would have his enforced labour on the lord’s demesne to remind him. I think it more likely that it was decoration simply there to entertain the community and perhaps to serve as a lesson that God loved a worker and had provided them with the means to live. |

|

|

|

Left: The West side of Burnham Deepdale font (above left) has just plant carvings. I wondered if they might represent the four seasons but there is no obvious Winter scene so perhaps not. On this side and two others we have well-drawn and very sinuous lions prowling around. The sculptor rather commendably seemed to know what a lion should look like! Right: The imagery has to be read from right to left. The months represented are: January - a man carousing with a horn drinking vessel; February - a man warming himself; March - a man digging; April - a man pruning a plant. |

|

|

|

Left: We see here the from right to left: May - a woman carrying a banner at Rogation tide; June - weeding; July - a man mowing; August - a man tying a sheaf. Right: September - a man threshing; October - a man barrelling wine; November - pigsticking; December - Four people seated for a meal at Christmas. Note there is no lion on this side. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||