|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

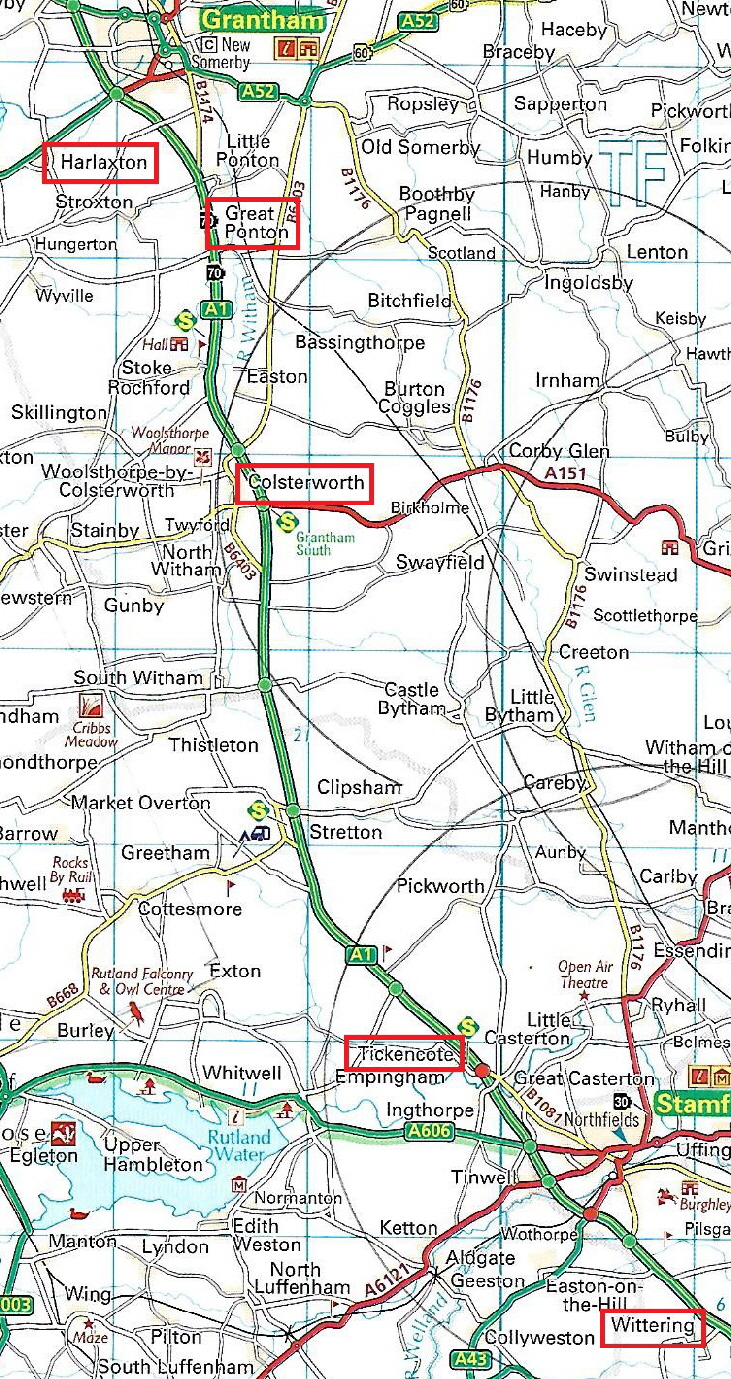

impress. If you are hurtling up or down the A1 I can’t think of a better place to interrupt your journey and chill out for half an hour. Stepping through into the nave you should try to cover your eyes, face east and then drop your hands suddenly. That way your breath will be taken away, as it should be, by the sight of the finest Norman arch in England sitting in one of England’s smallest county’s smallest hamlets. This church was the first I wrote about and now in 2020, ten years later, I am rewriting it and putting in photographs that will do it greater justice. When you see the exterior you don't know what to expect. That it is Romanesque is obvious. But it is faux Romanesque, with only a little of the original exterior decoration. Not only is it faux, but its fancies and follies along with its rather oddly positioned tower make it look Italian rather than English. It is baroque! It is also very attractive. This wasn’t the work of those usual suspects, the Victorians; it was commissioned by Eliza Wingfield in 1792 when George III was king and the French were busy cutting the heads of aristocrats in the Place de la Concorde. The church was very dilapidated at the time. Just possibly a decision to produce something sympathetic to the past without trying to mimic it was a masterstroke. Some will hate it for its lack of “authenticity”. I love it. What’s more it doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter because lurking inside is the most glorious Norman chancel arch in England. It is extraordinary, not least in its incongruous size. It sweeps across the entire width of the church with six orders of decoration. Beyond it is a beautiful Norman chancel with an extraordinary sexpartite rib vault, and yes some of it is restored but it really matters not at all. That chancel arch is the most impressive in England. Its Norman chancel is at least one of the most important. . The church is known, as is so frequently the case, to have replaced a Saxon structure but no obvious trace remains. The present church is believed to date from around 1130-1150. Just why it was so richly appointed is something of a mystery. The nearby town of Stamford has been an important one for at least fifteen hundred years. Tickencote is just a rural hamlet. It seems to have been gifted to the nunnery at Owston in Leicestershire in about 1160 but this seems to be later than the building date. It has been suggested that the chancel arch was in fact originally the west door of what was then a single-celled chapel. An outer strip of masonry that could conceivably be seen as a drip mould is advanced as an argument but that’s pretty thin isn’t it? We are entitled to ask whether such an ornate door to a single-celled structure is not even more unlikely than a chancel arch to a two-celled one. This was the first church I ever wrote about. In 2020 it was adopted by the Churches Conservation Trust who will ensure that this extraordinary Norman relic remains protected for posterity. To celebrate that I am rewriting the entry now, during the Coronavirus lockdown, with pictures which I hope will do it justice. If you have any interest in churches or in Romanesque art you will not drive past this church. Access from the A1 near Stamford is a cinch and takes you five minutes, if that. The nearby OK Diner is a great place to snatch a American style breakfast or burger lunch. Please visit and donate generously to the CCT. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

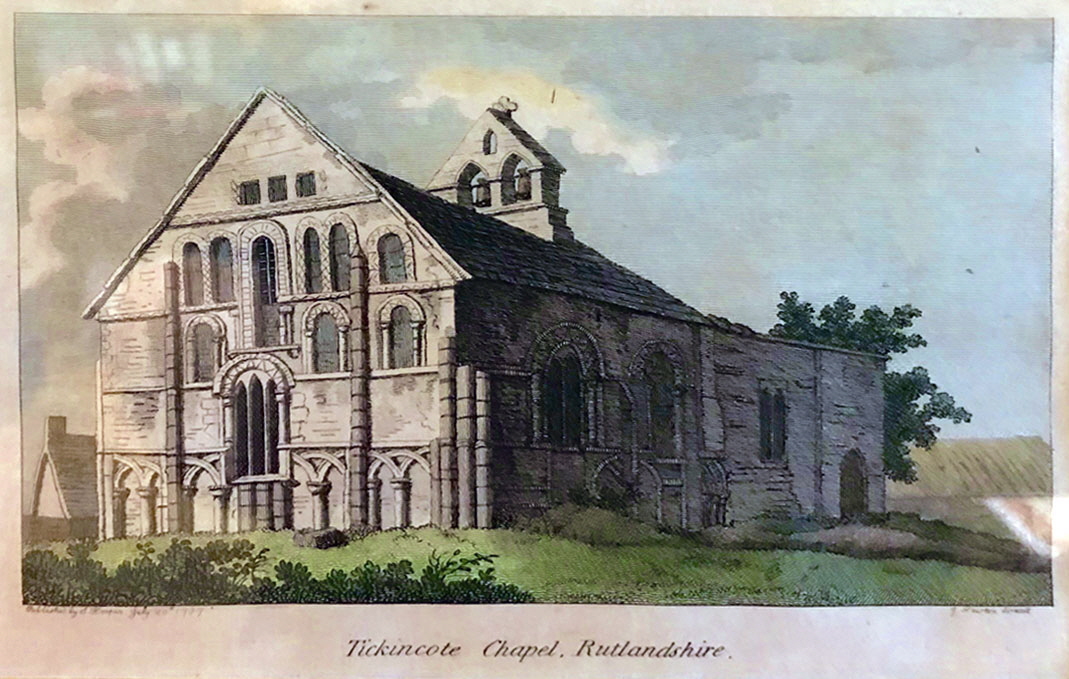

The church from the east end. I well remember the first time I saw this facade and being truly stunned. Iffley near Oxford had a similar effect. This is the most "authentic" Romanesque wall here but it soon becomes clear that is it is pastiche of original and re-modelled sections. The most obvious issue, as is true around all of the perimeter of the church, is the irregular blind arcading. What seems to have happened is that the vertical pilasters are placed at irregular distances. This causes problems when describing a semi-circle because there is no escaping the relationship between radius and pi. That is one of the reasons that Gothic pointed arches revolutionised architecture: you could now make the tops of arches reach an equal height even when the spaces they spanned were of different widths. Some of the blind arches higher up look original - and some do not. The full-height porch is from the rebuilding and sadly replaced a Norman porch and doorway |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This is what the fuss is about and if you don’t find it stunning then these pages are probably being wasted on you! Indeed, this is perhaps the finest Norman composition in England except perhaps Kilpeck. The chancel beyond the arch is Norman so too the font to its right. I have already said that it seems inconceivable that this arch would have been the doorway to a single celled arch. Well when you look something else should become obvious. How big would the doors have to have been to fill it? Note the remnants of earlier windows to left and right where there are now doorways, |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

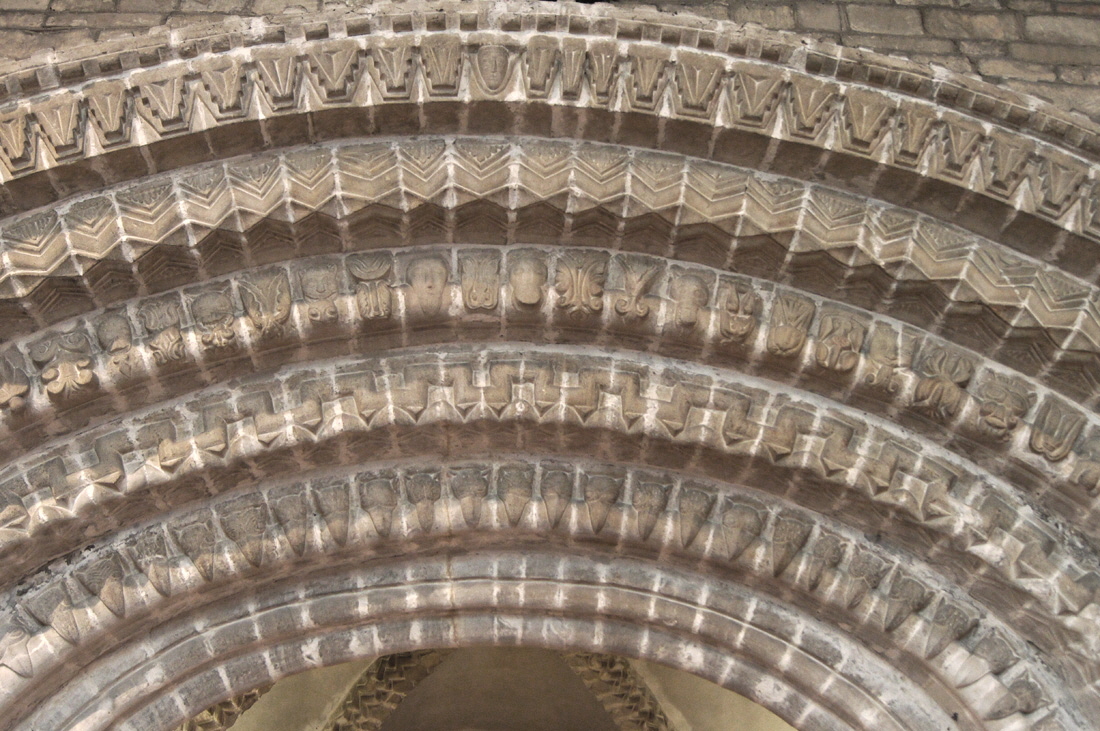

Detail of the arch. Of the five decorative courses, three have stylised patterns. The innermost is that most iconic of Norman devices - “beakhead” pattern. The great expert on English Romanesque - George Zarnecki - stated that the earliest appearance of beakhead in England was around 1130 at Reading Abbey.. Its form looks decidedly Scandinavian. Zarnecki believes it was based upon the beast heads which the Anglo-Saxons employed at such places as Deerhurst in Gloucestershire. It was, then, a Saxo-Norman device. Moreover, it seems for once to be agreed that this was a form that was native to England and exported to the rest of Europe rather than vice-versa. We know little or nothing about what it was supposed to mean. The outer course of historiated decoration is an eclectic mix of imagery. It is the sort of imagery that invites that tantalising question “what did it mean?” or even “did it mean anything?” I think we can assume it meant something or why go that much bother? But then we have to ask to what extent the meaning is in its totality - as we can assume is the case for the course of beakhead - or in the individual components. Either way, it is pretty unfathomable. Note the single face peering out of the decoration of the top course. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The chancel itself is a delight, the vault resembling one of those spiders with a tiny body and six great long legs (my cat having removed the other two as is his wont)! Admittedly the wide angle of the camera lens exaggerates the effect. It has sexpartite stone vaulting and is almost unique in England and is believed to pre-date similar work at Canterbury and Lincoln and once again we have to pinch ourselves to remind ourselves this church is in a tiny hamlet in England’s smallest county. The ribs are decorated with zig-zag moulding. At the centre of the ribs is a stone boss, again a great rarity, showing a monk’s head and two muzzled bears. Others exist at Iffley, Elkstone and Kilpeck. It is no exaggeration to say that this is one of the three or four most important Norman chancels in England and surely the most iconic. It has been restored but restored well and it is not always obvious what is old and what is (comparatively) new. The south side (to the right) is the most obvious remodelling but the whole is believed to be a very faithful restoration. There is a chamber above the chancel but the stairway that was within the walls was removed during the restoration. It can now only be accessed via the ceiling of the vestry. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Central Roof Boss in the Chancel with a monk and two muzzled bears. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The capitals on the south side of the chancel arch |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A Study in Romanesque. This picture is from the south side of the chancel. A transverse rib is flanked by two window spaces “stopped” with grotesque heads, |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Carvings from the chancel arch. Left: This fascinating image shows a man’s mouth emitting both vegetation and a snake. The snake’s head is prominent on the right had side of the man’s head. Centre: A man struggles over the edge of the moulding - his hair apparently on fire - behind him a creature. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Various carvings from the chancel arch. Creatures emerging from the mouths of others is a particular feature of this decorative scheme. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This form of animal carving is hard to define but it is so typical of Romanesque art. The snouts rest over the moulding of the masonry course. The eyes are vacant. These are examples of two favourite variations on this theme, Left: The ram. Right: The muzzled bear. The bear is ubiquitous in mediaeval carving and the Normans were particularly fond. When they are muzzled - and they so often are - it reminds us of bear baiting. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A Study in Romanesque II. A section of the chancel arch. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A Study in Beakhead |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The font is usually described as “thirteenth century”. I am rather at a loss as to why this belief prevails because the imagery of intersecting arches and the human heads at each corner are characteristic of many a font described as “Norman”! There is no Early English architecture here although I don’t now the date of the original nave which was completely rebuilt on its original foundations in the eighteenth century restoration. Pevsner puts the font’s date at c1200 - which is, I suppose, thirteenth century! Either way, we can simply accept that this a Romanesque style font and we don’t need to quibble which side of Pevsner’s date it belongs to because, frankly, we are all speculating. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking west along the nave. To say it is a poor relation of the chancel is an understatement. It was rebuilt on its original foundations in 1792 but we don’t know much beyond that except that the original was in gothic style. From the picture of the church in 1727 (below) we can see that it was not Romanesque and not very attractive. The faux Norman replacement is more in keeping with the Norman arch and chancel than the original but the windows are far too large! The bell on the floor is original and would have been hung in the bell cote that has been removed. Right: A rare wooden effigy of Sir Ronald le Daneys in the armour of a knight of Edward III. He was knighted in 1355 at Carcassonne in southern France. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

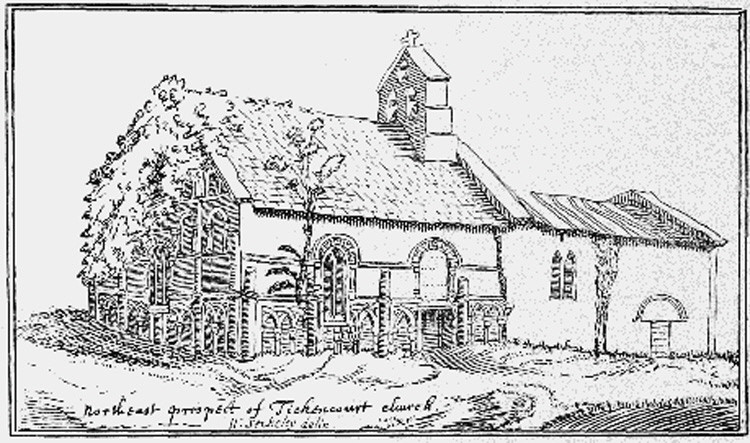

I am indebted to the Wingfield family website for this picture of the church as it was in 1727. It is particularly useful in allowing us to compare today’s east end with the original. If today’s east end appears at first as a somewhat fantastic confection then this picture proves that it was not so far from the original. The left side is blank suggesting that it had deteriorated and replaced with blank walling. The blind arcading was here in the original and you can see that the masons were geometrically challenged, The east window space had had an Early English style triple lancet placed within and it is quite possible that today’s window is closer to the Norman original than this was. Was that window later faux-EE or does it point towards the age of the nave? The rest is hard to make out. The chancel windows appear to be large and to have decorated heads. The nave, it has to be said, looks incongruous and of indeterminate age but decidedly Gothic. This adds weight to the argument that the chancel arch was originally a west door but I am still of the view that it is simply too large to sustain that interpretation. Note the bell cote. Note also that windows in the east gable that would have let light into the priest’s chamber over the chancel. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Thee church from the south side. The tower was built from scratch in the 1792 restoration and this is the church at its most “Italian”. Or at least “un-English”! It is pretty, however, and in good Romanesque style in particular the very pretty quadruple bell opening. The doorway is impressive. The chancel windows have a leaf moulding on their undersides which is not Romanesque at all. As I have said elsewhere, however, it has a charm all of its on and is well-executed. Certainly, however, there is a big incongruity between these windows as they appear on the outside and as they appear - deeply splayed and very Norman - on the inside. Right: The church from the north side. |

|

|

||||||

|

The nave from (left) the north and (right) the south. The non-Norman window decoration is very obvious here and the way that the actual windows have been inserted is rather odd. Why was it done this way? It is rather as if the original walls have been encased in a new outer shell. The arcading, again, is a bit of a muddle. We can see from the 1727 picture that there was none here at that point. The decision was obviously made to reproduce the original arcading of the east end on the nave. Perhaps ill-advisedly they also decided to use different styles of arcading in each bay and that has produced a somewhat muddled look. I haven’t checked whether the geometry is consistent but that doesn;t really matter because the design makes it look to the eye as if it is not - which is what matters. The string course look authentic. The decorative band below the eaves, however, looks - again - decidedly Italian. Or Greek. Or something. This whole composition, however, is true to itself as neo-Norman and is not intended as an “artist’s impression” of the original. It has integrity. |

|||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Left: The gable of the east end. At the bottom of the picture you can see detail of the “leaf” motif employed for the restored window spaces. The we see here, oddly, is not visible within the church at all window and gives you some idea that the priests room - if that is what it is - is a substantial one. We can see eight original-looking corbels here. None are showing in the 1727 picture, however, so if they are original where did they come from? Did the south side of the chancel - invisible in the 1727 picture, have a Norman corbel table? Right: The “new” south tower and entrance. |

|

|||

|

And finally, this is a sketch from William Stukely (1687-1765). Like the print shown above it shows the north side. It is very interesting because this picture shows that there was blind arcading around the wall of the chancel, despite its absence from the Wingfield print, but not around the nave. It also shows two chancel windows: one is blocked and the other has a mullion and is far larger than a Norman window. This tells us that there were changes before 1792. The nave shows a north door that seems to have had (before it was blocked) a rounded head, suggesting there was a Norman nave, despite the later window to its east. Perhaps that is the final nail in the coffin of the “west door” theory? Or does the lack of arcading around the nave suggest it was little later than the chancel? Note that the arcading all seems to be of a type, indicating that the 1792 arcading is, at least in part, of a style invented by the masons or their patron. |

|||

|

Footnote - William Stukely |

|||

|

Stukely is regarded as one of England’s first modern historians, if not the first. Earlier historians such as Bede had huge axes to grind either because of their allegiance to the Church or to the King of the time. To Bede, the biggest problem with the Vikings (who literally had axes to grind!) was not that they raped, murdered and pillaged but that they were “heathens”. Not like our jolly, honest Christian psychopaths at all. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, on the other hand, saw the world through the prism of the Kingdom of Wessex from whence they originated and so on. - although they are historically priceless. Writing history was a job where eulogising the ruler of the day was part of the job description. Or he might not like you. And you could then be History. Stukely did hugely important work, not least as the first antiquarian to properly explore Stonehenge and Avebury as well as many other ancient stone circles. In 1729 he was ordained Vicar of All Saints Church, Stamford. Stamford is a town in which Diana and have both lived and which is still very much part of our social lives. Stamford regards Stukely as one its most famous sons. The trouble is that Stukely was a bit of a fantasist. Or let’s us say that the quality of the evidence he relied upon would not meet modern standards of diligence. Hence he claimed that Boudicca’s army crossed a ford on the River Welland near Stamford during her campaign against Rome. It didn’t. He claimed that his house (which you can still see) in Barn Hill in Stamford was on the site of the house where Charles I spent his last night before being captured by the Roundheads. The inn was in fact in Water Street. a quarter of a mile away. I like to poke fun at historical figures but Stukely was, in fact, a very serious historian and his fame is deserved, |

|

The A1 Trail |

|

|