|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

easternmost bays of the arcade where the arcade arch soars upwards to also encompass the triforium arch. The crossing is overwhelmingly Norman and cathedral-like in its scale and impact. On the east side of each transept is a small apse that formed the sanctuaries, so very reminiscent of European Romanesque churches but distinctly rare survivors in England. The north aisle was screened off from the nuns and used as the parish church. By about 1400 the aisle had to be widened and the north transept used in order to accommodate the town’s growing population. As with several abbey churches, the parish was able to negotiate its retention for the use of the town after the dissolution of the monastery, in this case for a payment of óG100. The windows above the altar were replaced in the Decorated style in about 1300. Below them and to their east you can see two other Gothic windows. These are part of St Mary’s Chapel in the retro-choir beyond the high altar. Lady Chapels were not flavour of the month during the Reformation and it was demolished and replaced two mini-chapels dedicated to St Etheflaeda and St Mary. The original arches, however, were retained and for this we can be very grateful because they are adorned by splendid Norman carved capitals. The double chapel is flanked by another smaller one on each side dedicated to St George and and to St Anne. These are apsidal from within but sit within the rectangular east end. The outside the church is adorned by one of the most comprehensive carved corbel tables in England - although it is not always which are original and which are replaced or re-cut. At least two are “famous”: the birthing corbel and the sheela-na-gig - of which more below. There is so much to see here that it is perhaps better to let the pictures speak for themselves. I must mention, however, two Anglo-Saxon roods - crosses - that are preserved here. One is inside the church and the other outside. To have one at a church is fortunate indeed; to have two - well, that’s downright greedy! |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

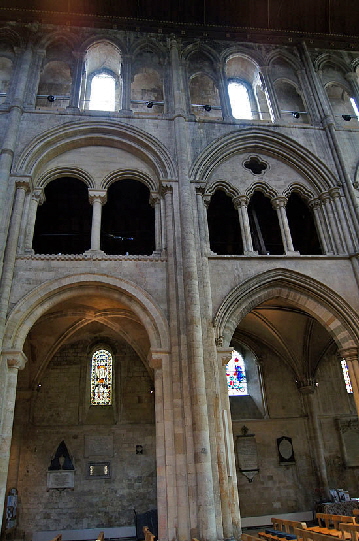

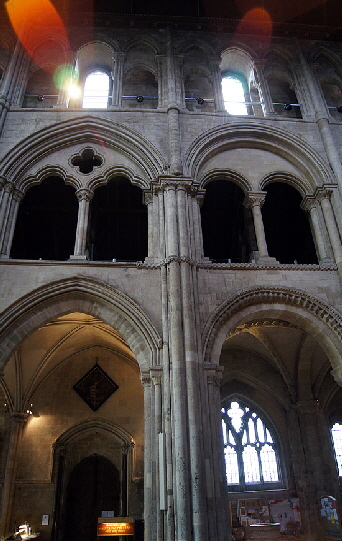

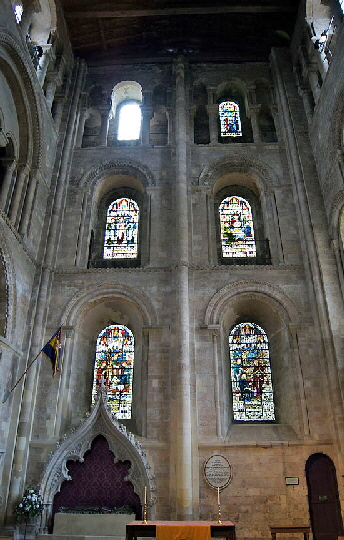

Top Left and Right: It is hard to overstate the initial impact thus church makes. These two pictures are looking towards the east end. There is much to note. Start with the great height of the crossing arches. Above them you can see the gallery surrounding the interior of the tower. Note also the way the double arches of the eastern chapel and the choir arch beautifully frame the Decorated style windows at the east end. Notice also the plainer and rounder and arches of the easternmost bays of the nave arcade. These are the oldest bays and the style changes as you move to the west. Lower left: The south arcade looking towards the west end. You will notice hardly any two triforium arches are the same. Note the way the arches become slightly pointed at the western end - and this is even more apparent on the arcade arches themselves. The Norman triforium arch second left has a purely decorative insert that splits the arch into two smaller ones. The Church Guide suggests that these are unique to this church. Further west these areas are filled in. The three westernmost triforium arches are pierced by quatrefoil designs, The arches themselves have sinuous curves rather than semi circular openings. By the time the masons reached the west end itself the triple lancet window they installed would have been de rigeur. In fact, triple lancets at the west end are quite uncommon - but this was no ordinary church, of course. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Many large churches are now installing spotlights to improve the visitor experience but, unfortunately, they are the scourge of the photographer, so apologies for the flare in these pictures. They show the great diversity in the architecture of the bays of the nave. Left: Here you can see the far south western bay with its hefty round pillar. Remarkably, it stretches up to provide the springing for the arches of the triforium above. Notice the abundance of Norman dog tooth moulding on this bay. The dog tooth diminishes as the arcade moves west reflecting its diminishing fashionability as the Norman period moves through the Transitional to the early English Gothic. This is the one bay that is unequivocally Norman. Centre: We are looking now at the north arcade and you could deduce that by noticing that the right hand bay has round headed arches and some dog tooth moulding. The left had bay, on the other hand has a pointed arcade and new-fangled ogee (s-shaped) arches in the triforium above. Note, however, that the masons have stuck with a consistent design on the clerestory above: triple openings with a single window beyond. It’s not hard to see why they were consistent. The clerestory was, of course, visible from the outside and style changes would have marred the external appearance. This clerestory is very sophisticated and I wonder if was added after all of the arcade and triforium was completed? Note that it too has a very narrow (probably vertigo-inducing) passageway. Right: Another transition, this time on the south side again. The round arch on the left is very plain, Transitional rather than Norman or Early English. The bay to its right is very different. This bay and its two neighbours to the west are later than those to its east and the stylistic change is quite marked. We are now very firmly in the Early English era. In all of these pictures note also how the vertical columns change from the round drum-like style of the Norman pillars to clusters of thinner columns. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The east end. Right: Looking towards the west end from the crossing. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking east into the north aisle from the crossing. Note the hefty construction of the gallery opening with its big fat column. Yet it and the arch below are quite delicately encompassed by shafts that make it into a quite sophisticated composition. Centre: The roof of the north aisle is a series of Norman quadripartite vaults. Right: The south transept with three pairs of the Norman windows. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the east end from the south aisle. Centre: The apsidal south eastern chapel dedicated to St George. You can see a sculpture of the saint slaying the dragon behind the altar. Note the quadripartite vault and the narrow blind arcading either side of the window. Right: The chapel of St Mary in the retro choir at the east end of the church has this well-preserved thirteenth century wall painting depicting scenes from the life of St Nicholas. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Four Studies in Norman Triforium arch design. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The triforium even extends around the interior of the tower crossing. The painted roof is Jacobean. Right: The sixteenth century reredos of St Lawrence Chapel located in the north transept. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

One of the two Anglo-Saxon roods at this church. This one is in St Anne’s Chapel. It is tenth century and extraordinarily well preserved. The Anglo-Saxons did not like to represent Christ in pain, so the Christ figure is naively represented. Above Christ’s head two cherubim hold wands and prepare to escort Christ to heaven. Longinus is bottom left with his spear, Stephaton with his vinegar-soaked sponge is bottom right. The Virgin and St John are either side of Christ. Traces of gold and jewels have been discovered on the cross so it is believed that it may have been a gift from King Edgar. What an extraordinary treasure this is. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Romsey Abbey has one of the finest collections of Norman carved capitals in England. This one is very special. It is a battle scene. Two kings face off in the centre but their swords are being restrained by angels. The one on the left seems to have the other by the beard! To his left is a decapitated body. To the right of the other king is the severed head. There is speculation that it represents the battle of Edington - or Ethandun as it was known then - in AD878 when King Alfred the Great defeated Guthrum the Viking leader. The Treaty of Wedmore freed Wessex of the Danes and Guthrum converted to Christianity and retreated to the Danelaw. The clutching of beards represents discord so this scene presumably depicts the fighting being ended through divine intervention. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Norman capitals. I am not going to speculate about what they all mean. Your guess is as good as mine in most cases! Worthy of note, however are : Top Right: Traditionally these heads are thought to be of King Stephen and his daughter Mary who was one-time Abbess. Second Row Centre: This seems to a representation of one of the “labours of the month”, in this case Ploughing. Third Row Centre: Two labours of the month: Reaping Corn (September) and Warming Hands by the Fire (February). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The corbel tables of Romsey Abbey are extensive and interesting. Problematically, many have been re-cut or replaced - but it is not always obvious which is which. Many or most of them are duplicates of those already there so they are extremely authentic to look at. Take for example, the viol player who appears in both the first and the third rows in the pictures above. The on at the top clearly looks much older than the one below. There is a huge amount of cat faces. An absolutely splendid website by a gentleman called Roy Romsey explains that this was likely to be because cats were the only pets nuns were allowed to have. I must confess that information really astounded me but he has some excellent contemporary quotes to prove this is not just speculation. Several of these cats have creatures or people in the mouths as you can see above. The corbels here are mainly of heads - men, women or cats - and there doesn’t seem to be much in the way of Christian or zodiacal symbolism as you would find at, for example, Kilpeck or Elkstone. In the fifth row, second right is the “birthing corbel” whioch is believed to be unique. See also the carving on the left of that row that looks like a group of sticks tied with rope. It appears several times here but also at the tiny parish church at Stoke-sub-Hamden in Somerset. It obviously has a meaning but I have no idea what it is. For a complete set of pictures and features on the corbels at Romsey you should visit Roy Romsey’s site at http://romseys.wix.com/romseyabbeycorbels. It is splendid and there is no point in my trying to reproduce all his work here. Bravo, Roy. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The second of Romsey’s roods on the western wall of the south transept. It is early eleventh century. It was probably removed from the chancel arch of the Anglo-Saxon church. It is suggested that like the other Romsey rood and the one at nearby Breamore it was originally flanked by images of John and Mary. This is a rather more lifelike Jesus still, however, shows no sign of true suffering nor even nails.. He is a remarkable 6’9” in height. Top Right: The hand of God (The “Manus Dei”) that reaches towards Christ’s head. Interestingly, as with modern Islam, Christians in the first millennium would not represent an image of God, presumably remembering biblical exhortations about worhsipping “graven images”. Lower Right: This, remarkably, is a sheela-na-gig or female exhibitionist. It is on the east wall fo the south transept. The pudendum is represented by a mere nick so this is an unusually discreet sheela. For a real humdinger see the one at Kilpeck. She apparently is carrying a crozier so it is widely interpreted as a satire on the abbess. Other more esoteric theories have also been proposed but you will have to search for them elsewhere! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The north aisle. You can see that it has been modified at some point and a couple of really ugly windows inserted. The clerestory, however, with its groups of two blind and one glazed arch is intact. Right: The church from the south west. Note the apse at the east of the transept. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The south aisle and clerestory looking west. The changed configuration of the clerestory suggests changes were made. Indeed, in many places on this side of the church the corbels are a long way short of the roofline suggesting that the roofs have been raised. Right: The west end with its classic Early English triple lancet window. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The church from the north east. As you can see, the Norman tower can only peep from behind the massive chancel and transepts. This church has all the height of an Anglo-Saxon church (which it isn’t) and the stumpiness of a Norman tower. Note the carved corbels. Right: The Abbess’s door on the angle of the south transept and the south west aisle is Norman - but it looks late Norman with its course of rosette decorations and sophisticated columns. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The south trannsept from the east. It is on this wall that the sheela na gig is located, Centre: The Abbess’s door on the south aisle next to the transept. Right: The south transept from the west. Note the triple Norman window that predicts the triple lancet window arrangement that would almost define the early English style. The rood is at the foot of the wall next to the abbess’s door. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||