|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

What we do know is that by 1393 the church was a chapel-of-ease for St Wilfred’s chapel in nearby Brougham. In 1273 Brougham has been inherited by the Clifford family and the centre of gravity had very much shifted there. No doubt the depredations of the Great Plague of 1348 and subsequent outbreaks hastened this. Anne Clifford, once she had sorted out her long-running inheritance saga in 1643, threw herself into reinvigorating the family estates with some vigour. The rebuilding of Ninekirks happened in 1660 and Lady Anne’s initials are set into the plasterwork above the east gable of the church. It is no exaggeration to say that you could add an appropriately-dressed congregation and transport yourself back 450 years, such is the unchanged nature of the church. There is no chancel arch or aisles here: this is an austere single-cell church with only token separation between congregation and clergy reflecting the Puritan philosophy of the Cromwellian period although there was originally a door across the centre of the screen at one time. Oliver had, in fact, died in 1658 to be succeeded by his son, Richard, who was quickly removed by the leaders of the New Model Army and 1660 saw not only the rebuilding of Ninekirks church but also the return to England of the King-in-Waiting Charles II. It is not an architectural gem but a fascinating time-warp building best described via the photographs. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the east end. This is a church dominated by the wooden fittings, particularly the pews and benches. Right: The box pews for the gentry on the north side. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The box pews seen from the east. Right: On the south east of the church is this rather lovely piece of oak panelling surrounding the ornate priest’s door. The CCT speculates that it comes from an old vestment chest but whatever its origins it is an unusual and attractive item. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Some of the carved adornments from the priest’s door cabinet-work. Was it a vestment chest? Well, you’ll have to make your own minds up but there is a distinctly secular - not to mention pagan - look about some of these. The man on the left is playing what is surely a military drum. All of the men sport beards. The middle three designs also feature what might be a raspberry or an acorn. The two female figures on the right look like they might be goddesses of some sort. Anyway you look at it, they are not the stuff you would expect on a vestment chest! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The “Vestment Chest” also has a couple of nice dragons. Right: The oak altar table really couldn’t be much simpler! The pre-Reformation altar slab sits on the floor beneath. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I have to admit to be no great fan of church brasses. Do you remember those days when the average suburban lounge would proudly display a “brass rubbing” of some mediaeval knight or other? Well for my money they beat nail and thread pictures and “Prints for Pleasure” but I never could quite see the attraction. These brasses at Ninekirks, however, are very fine indeed and because they post-dated the Civil War they avoided the fate of being melted down for bullets! These are very aristocratic brasses and in a different league to those seen so often in East Anglia and the Cotswolds celebrating the “new money” of the wool merchants. The large slab shown in the three photographs to the left has a date of death of 1570 so it seems that they may have either predated the rebuilding or the brasses themselves post-date some of the actual deaths. In any event, these brasses commemorate the de Brougham family - see the footnote below. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

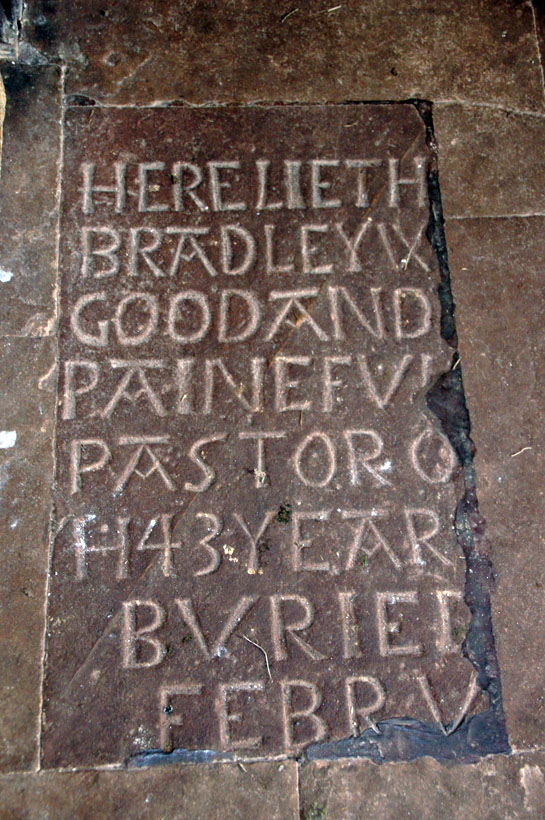

Left: A simple memorial to some previous rector. Even in English the full text is not easy to understand! Centre: An oddity of this church is that you can lift a massive wooden trap door near the altar and reveal this memorial believed to be to Odard and Gilbert de Burgham and therefore of the C12 and part of the original church. Right: The sandstone octagonal font dated 1662. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Many churches have a hatchment or two - but Ninekirks has three. Hatchments were an odd tradition dating from C17. The arms of the dead man or woman would be hung usually at second floor level of the deceased’s house before being moved to the family chapel or the local church. All of these examples are, needless to say, of the Brougham family. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The massive parish chest which surely remains from the original church. Right: You don’t see this is many churchyards: the remains of stables. It is c18 and was for the parson’s pony and trap! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The rather stern reredos. Right: Anne Clifford’s initials above the eastern gable. You might be wondering - as we did - why the initials are “AP” and the CCT’s information board doesn’t explain. In fact it stands for “Anne Pembroke” because by now Anne was Countess of Dorset, Pembroke and Montgomery as well as Baroness de Brougham! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote 1 - Finding the Church |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This is not an easy place to find. You need to take the A66 out of Penrith. After a couple of miles you will see signs to Brougham Castle on your right. About 1/2 mile further on along the A66 you need to be looking for a small grey gravelled car park on your left and slightly below the level of the road. It’s not easy to spot until you are nearly past it but look for a large farm almost straight opposite on the right hand side. If you see signs to Center Parcs on your right then you’ve gone too far in which you can use their entrance to turn around. The A66 is a very busy road, however, and turning across the carriageway is not for the faint-hearted - as I found out! Once you are in the car park there is a CCT sign to the footpath. Once you are on it you need only follow your nose along a well-trodden footpath for about a mile - a very pleasant walk unless it’s raining! |

|

Footnote 2 - Lady Anne Clifford |

|

Lady Anne is beloved of female historical fiction writers. She was a strong-willed and “high-achieving” woman in what was very much a man’s world. Born in 1590 at Skipton Castle and a childhood favourite of the aging Elizabeth I, she was the only surviving child of George Clifford, 3rd Earl of Cumberland. However, Clifford left his estates to his brother, Francis, who became the 4th Earl. She was left £15,000 - an enormous amount - but the fact was that Edward II had created the title under the principle of primogeniture. The excuse was that she was only 15 at the time she should have inherited. It was only on the death of her uncle in 1643 without a male heir that she was able to secure the family estates and even then she had to wait a further six years to gain possession. Throughout that period Lady Anne adamantly refused to renounce her claims. She had two husbands both of whom by all accounts, became bored with her obsessive campaigning and even contemporary writers suggested that she would not have been an easy companion! When she was granted a further £17,000 in compensation in 1617 her husband trousered the money himself! Once she had taken possession, Anne spent considerable time, money and energy in restoring them, and the church at Ninekirks was one such project. Her peregrinations around her estates were the stuff of a legend at a time when little was expected of the female nobility. You might think that she was unfortunate to inherit only when she was in her declining years but, remarkably for the time, she lived to the age of 86 dying at nearby Brougham Castle. Brougham Castle (owned by English Heritage) is nearby and it would be folly to miss seeing it when you are in the area. Lady Anne is interred in the church at Appleby only 12 miles from Brougham. If you are intrigued by Lady Anne and you are prepared to travel further afield then do visit the very interesting Skipton Castle in North Yorkshire. It’s a great place to visit as it is bang in the middle of the every attractive town. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote 3 - Brougham Hall - and Lady Anne again! |

|

Just as it would be a shame to visit Ninekirks without seeing Brougham Castle, the same is true of Brougham Hall. Lady Anne Clifford bought it for £1000 from the Brougham family in 1651 and, in her usual style, set about renovating and improving it. The family re-acquired it in 1726 for £5000. Then, in the words of the Hall’s website : “Brougham Hall again passed out of the ownership of the Brougham family in 1934 and rapidly fell into decay. It was then abandoned, roofless, and commandeered by Winston Churchill for the development of one of the Allies five most top secret weapons of WWII. This only served to further its decay. An extensive programme of restoration, which was to become one of England's most ambitious country house restoration projects commenced when it was bought by Christopher Terry, in 1985, who saved it from destruction” Diana and I visited it in 2014. There is no admission charge although as you enter and leave a disembodied voice will plead with you for a donation towards the restoration project. Inside you will find interesting little shops, a micro brewery, a cafe and a whole host of interesting snippets about the history of this ancestral pile. It really is a fascinating place and does deserve your support because this is a private restoration project: it is not being paid for by the Government. It’s a nice visit and you’d be mad not to pop in. There is a church within the grounds - sadly locked when we visited. Sure enough, it is Lady Anne’s work of 1659 - predating Ninekirks by just one year - and you can see a picture of it below. I hope it looks familiar because it is spookily similar (although not identical) to Ninekirks. What more reason do you need to visit? |

|

|||

|

|||

|

|