|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

deemed to be too small or was destroyed in about 1100 and replaced by a Norman structure a little further uphill on a slightly shallower slope. The chancel arch is Early English from around 1250 so, the theory goes, this replaced a smaller Norman one. Another theory is that, bizarrely, there were two Norman churches here and the lower of the two was demolished leaving just its tower! You might find it odd that we can’t place this tower definitively as either Saxon or Norman, but in fact there are few architectural features to date it. Even if there were (a triangular-headed window, for example) the Round Tower Society whose members think of little else would remind you that Anglo-Saxon builders didn’t just all go off and grow a few turnips after the Conquest: they were used to build “Norman” churches and clung for a while to their traditional methods. There must also be the usual debate as to whether this round tower had a dual role as a defensive stronghold. This theory has taken something of a battering in recent years. The only comment I would make is that this theory seems much more common when associated with round towers! The usual explanation for round towers in Norfolk and Suffolk is the lack of quarries to provide stone corner blocks. That these counties were vulnerable to Viking attack is indisputable. However, the last serious Viking incursion was in 1070 and this was an invasion, not a raid. It is not impossible that the need for defensive towers were still seen as an insurance policy in some areas, but was Little Snoring, some 20 miles from the sea really threatened, especially with the war-loving Normans ruling the country? I would suggest that the defensive theory is only viable here if the tower is indeed Anglo-Saxon rather than Norman. Apart from the tower, the south door is the principal point of interest. It must be unique, consisting as it does of a round headed doorway within a pointed, yet Romanesque pointed arch surmounted by another round arch. Pevsner reckoned the pointed arch with its Norman zig-zag decoration to have been reassembled from a round headed arch. This idea fits nicely with the idea of a second church having been demolished. My observation based on seeing dozens of such “re-assemblies” is that they are generally badly bodged with asymmetric sides, a lopsided appearance and amateurish mismatches of the decorative patterns at their apex. This arch exhibits no such qualities: it is geometrically perfect and beautifully assembled with a beast’s head carving as its keystone. It looks more to me like a piece of Transitional architecture in its own right. Convince me otherwise if you can! Nobody explains the slim outer blind arch, itself clearly Norman. There is also a Norman font here and if you are a regular reader of these pages, you might be thinking that this is why I really write about this church. You would be wrong! I love the simplicity of its interior. More than that, however, I was thrilled by the much more recent historical artefacts of wooden boards at the west end of the church recording the exploits of the RAF squadrons based at Little Snoring during World War II and for whom this church served as a chapel. More of this anon. |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Left: The tower with its obvious evidence that it was formerly attached to another building. The outline of that building is clearly visible. Compare the height of the roofline with that of the current church. The old building was much higher, wasn’t it? Look at the height of that priest’s “spy hole”. This height of nave, in my view, is more typical of an Anglo-Saxon structure, not Norman and this makes a secondary defensive role for the tower that much more likely, albeit still speculation. Moreover, it does seem to me that a Norman building replacing a Saxon one is much more plausible than the rather far-fetched notion of two adjacent buildings. Centre: The filled-in original west end tower arch, again bespeaking of a substantial original structure. The doorway is of indeterminate date and both it and the surrounding stone in-fill seem to have gone through a number of changes over the centuries. The carving of a head is also of unknown date. Right: The peculiar three-arched doorway. |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

A closer look at the south door. Note the beautifully proportioned pointed arch. It’s not Romanesque, of course, but the style of decoration certainly is Norman. I find it hard to believe that it it is a reconstruction. The whole composition is mysterious and complicated further by the fact that the capitals (see below) do not appear to be Norman. The Church Guide asks whether the outer decoration with its horseshoe shape and foliage pattern was influenced by Middle Eastern designs seen on the Crusades. I would suggest the same for the pointed arch. |

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Left: The keystone carving on the south door arch. Again, I have to say this composition shows no sign of having been reconstucted. Right: The (obviously re-sited) head set with in the tower’s blocked eastern arch. |

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

The south door capitals. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the east end. It’s a simple and unadorned interior. Simon Jenkins describes the church as a “friendly structure”, referring to the use of whatever stone was available. I know exactly what he means, and I would extend this description to the whole church. It is an unintimidating place and (glory be!) is not disfigured by wall monuments to the not-quite-great and not-so-very-good! It’s a nice place! Right: The west end - and a photograph marred by an inexplicable ghostly reflection! On the west wall are the commemorative boards for the RAF squadrons. |

|

|

|||||

|

Left: The simple chancel. This is an Early English structure and the triple lancet east windows are typical of the period. Right: The unusual piscina is set within the junction of the south window rebate and the south wall. Rather charmingly, it has its own little tie bar between the pillar and the wall! |

||||||

|

|

|||||

|

Left: A general view of the church taken from the raised area at the west end of the church. The Norman font is in the foreground. The coat of arms above the door is a rare James II example: bear in mind that he ruled for only three years before he was overthrown by William of Orange in the “Glorious Revolution” of 1688. Right: The stylised decoration of the Norman font. |

|

|

||||

|

Two more views of the font. |

|||||

|

|

A section of one of the boards recording RAF Little Snoring’s “victories”. These are most extraordinary, showing the date, names of the aircrew, location and the type of “downed” enemy aircraft. The fact that there are two aircrew tells you that these were two-seater aircraft - the de Havilland “Mosquito” in fact. The numbers “23” and “515” refer to the two squadrons based here. This board is from late 1944 so many of the victories are recorded over German cities such as Bonn and Frankfurt-am-Main. We see bombers such as the Heinkel He111 but also fighters such as the Messerschmitt 109, 110 and 410 as well as the Focke-Wulf 190. The British bombed Germany by night whilst the Americans did so by day, so we must assume that these “kills” were in a night fighter escort role. German readers must forgive me if they see this picture as yet another manifestation of the perceived British obsession with “the war” but to me these boards are every bit as valid historically as the other artefacts we see in English churches - and, of course, we might wonder how many of these RAF airmen themselves survived the conflict. |

|

|

||

|

Left: The blocked north door of the church. This is in “Transitional” style, rather reinforcing my suspicion that the pointed south doorway is also of thie period. Right: This view from the south west gives a better idea of just how large the tower is compared with the rest of the church. Note the variegated masonry courses. The tiled conical cowl and its rather charming “dormer windows” date from around 1800 and enhance rather than mar its appearance. Note the narrow slit windows with trefoil heads that are neither Saxon nor Norman! |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote 2 - Words from that nice Herr Goering |

|

Goering was, it seems, the comical face of the vile Nazi leadership. Obese, pompous and outrageously dressed he was a comic gift to the likes of Carl Giles, the celebrated cartoonist whose light-hearted view of the war is a delight to this day. Goering - by no means a stupid man and himself a First World War fighter “ace” - was also good for a quote and he had these words to say in January 1943 about the Mosquito aircraft (and we must acknowledge they perhaps lost something in the translation!). Try to imagine a British war leader expressing such “unpatriotic” sentiments: "In 1940 I could at least fly as far as Glasgow in most of my aircraft, but not now! It makes me furious when I see the Mosquito. I turn green and yellow with envy. The British, who can afford aluminium better than we can, knock together a beautiful wooden aircraft that every piano factory over there is building, and they give it a speed which they have now increased yet again. What do you make of that? There is nothing the British do not have. They have the geniuses and we have the nincompoops. After the war is over I'm going to buy a British radio set - then at least I'll own something that has always worked." |

|

Footnote 3 - Dennis Wall - a Soldier’s Story |

|

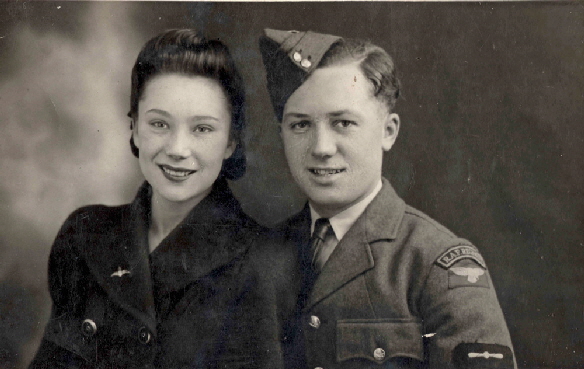

My father, Dennis Wall, was in the RAF Regiment as a private soldier from 1940 until the cessation of hostilities in Europe. My dad always wanted to be a soldier and he “joined” up just after his seventeenth birthday. He didn’t talk much to the family about “his” war because he always thought - wrongly - that we would be bored. Dad was in France with the British Expeditionary Force and guarded RAF airfields that were equipped with the dreadfully vulnerable, slow and obsolete Fairey Battle medium bomber. The Luftwaffe fighters shot them down like picking apples from a tree and most of the pilots never came back. Dad told me that at one of his airfields he experienced what was the first air raid on an RAF base of the whole war. One day he was sent with a truck to get some supplies and when he returned the whole base had packed up and left for the Channel ports. Dad managed to find his way to Dunkirk, or some port near it, and was eventually evacuated. He told the story of arriving at Dunkirk without any weapons, He queued for a rifle but by the time he got to the head of the queue there were none left. “I was left to face the Panzerkorps armed with a bayonet”, he told me. He was always scathing about the propaganda and the post-war glorification of the evacuation exercise that was, in reality, a bloodbath. He told me that the many films showing cheerful Tommies going home were actually of soldiers going out to France months earlier. You could tell, he said, the real films of the evacuation because everyone was exhausted and nobody was smiling. I think he would have enjoyed the blockbuster movie of 2017 but I know he would have said that it got nowhere near representing the real horror of the relentless attacks by the Wehrmacht and the Luftwaffe. Dad was an adoptee living with his adoptive mother, Sarah, in Aston, Birmingham. An illegitimate baby of the daughter of a well-to-do family he was given away and I am not sure the adoption was ever official. Dad met my mother, Doris, for the first time in the pub across the road from Sarah’s home after the evacuation. He told me that no Dunkirk veteran ever had to buy himself a drink and he was generously supplied with cigarettes by the RAF. With what turned out to be tragic consequences he persuaded my mum to try smoking. His first two postings after Dunkirk was RAF Henlow in Bedfordhire. He was also at RAF Cranwell for a time. Dad’s was an unspectacular but “interesting” war. He lost his only promotion to corporal after being found lying drunk and incapable on a runway at a Gloucestershire airbase! He won no medals for bravery, although several for good conduct and for various campaign medals. I know little about his progress after Dunkirk, but the extent of his travels can be judged by the fact that I have photographs of him at Belfast (Northern Ireland) in 1940; Bittan ( Egypt); Brussels in 1944; Volkel Airfield (Holland) 1944; and Copenhagen in 1945. I know he was in Paris before Dunkirk because he told me that it was in a whorehouse there that he lost his virginity! I think he lost it quite a few times as the war went on. Dad told me that he became the driver for a Scottish colonel for a while in Germany in 1945. He was told to drive somewhere to collect the colonel and decided to take a detour. That was April 16th 1945. En route he saw a place called Belsen just one day after it was liberated. After the war the colonel offered my father a job on his Scottish estate but he turned it down. How different my life would have been had he accepted it. After he was demobbed, my parents settled into a council house in Aston and my older brother - also Dennis - was born in 1945. My dad told me just before he died that he had wanted to be a soldier all his life and wanted to continue his service career after the war. Mum put her foot down and so they reached a deal that we would remain a reservist which would entail his being away at training camps for two or three weeks a year: his annual “fix” of soldiering! |I was born in 1952 and my parents were allocated a new council house on the eastern outskirts of Birmingham. One of my earliest memories is of my father coming home one day (I don’t know from where) in uniform and my mum crying because she thought he would be “called up” for the Suez Crisis: this then was 1956. My father told me just before he died that on one of his army training absences in Cumbria he received a message that his adoptive mother, Sarah, was very ill. The CO encouraged him to visit her and offered leave and a travel warrant. My dad so loved his army “holidays” that he refused. Sarah died days later and my father died with that on his conscience. Dad never articulated any animosity towards Germany or its army, beyond the usual feeling of irony about its post-war “economic miracle”. He reserved what little venom he had for the France of General de Gaulle that in his view air-brushed the part of Great Britain played in its liberation from its memory, preferring to think that they did it all themselves with a bit of help from the USA! I don’t know when Dad stopped soldiering altogether. In 1957 my mother was admitted to hospital with what I could not to know was terminal lung cancer. She died at home in 1958 aged 32. Mum had, in the language of the day, “smoked like a chimney”. My father’s largesse with his cigarettes after Dunkirk led, as he himself admitted, to mum’s dreadfully premature death. Dad remarried in 1961 to someone that brought some money and a great deal of unhappiness into his life and lived an otherwise uneventful life until he died of a heart attack in 2008, aged 86. Until the day he died he loved the RAF and thought of the war as being the best days of his life. He had travelled extensively, smoked, drank - by his own admission sometimes demanding drink at rifle-point - whored and made friends. I have no idea whether he ever killed an enemy soldier or even fired his rifle in anger. His was an active, albeit largely defensive, role so I suppose he must have done, but he never said so. This is the story of an everyday soldier who fought almost throughout the war in Europe. Nobody called him “hero”. Nobody put out bunting to mark his safe return. Nobody thought he needed “counselling”. He was just one of the squaddies that got on with it, managed to stay alive and return, complete with “demob suit”, to a country of austerity and limited opportunities. Birmingham where I was brought up was bombed badly: it wasn’t only London and nearby Coventry that “copped it”. Huge bomb sites were around in my city up until my teenage years. A factory in nearby Castle Bromwich was one of the largest producers of Spitfire aircraft and it was still derelict when I left the area aged 17. The Civil Defence Corps were still practicing with barrage balloons during my childhood. Why do I place this little story here? Well, as I studied the boards at Little Snoring Church it struck me that such men as fighter pilots left their mark on the world. Theirs was a war of one-on-one combat and feats of derring-do. Even a bomber pilot would not have his achievements recorded in this way. And then there were the the little men, like my father, in their hundreds of thousands who “did their bit” and were quickly forgotten. As survivors they were not listed on war memorials or recorded in our parish churches. Nobody has lists of the brave men who risked their lives for years on end and managed not to get killed. Dead = hero. Survivor = forgotten. Funny when you think about it. I can’t help reflecting that nothing I have done in my lifetime comes close to matching the remarkable experiences of him and millions like him from dozens of countries during that period. It just makes me feel very humble. We weren’t close - my stepmother saw to that. Nor am I going to pretend he was my childhood hero - lots of us kids had ex-serviceman dads so it wasn’t seen as a big deal - but as I have got older and more thoughtful I have huge respect for what he did. It’s a good feeling that the internet gives me the opportunity to commemorate in some small way the lives of my two very ordinary parents who lived through an extraordinary time. |

|

||

|

Doris Wall 1926-1958 (wasn’t she gorgeous?). Dennis Wall 1922-2008 (wearing anti-gravity hat!) |

||