|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Christianity and was one of England’s earliest saints. His daughter, Ethelburga, was also a Christian and also a Saint (in those days sainthoods were awarded to Christians aristocrats with the same profligacy as knighthoods are granted to today’s senior civil servants, it seems: you just had to be there!). In AD625 she married King Edwin of Northumberland, who also converted in AD627. You will be astonished to hear that he too became a saint. Cynic, moi? Anyway, Paulinus (yes, yes, he was also made a saint...and the first Archbishop of York to boot) accompanied the happy couple to the royal residence at Ad-Gefrin and stayed there, according to Bede, preaching and converting for 36 days and in doing so, no doubt, launched a few more saintly careers. And Ad-Gefrin was just a mile from Kirknewton. As I say, it is a little tenuous because the parish of Kirknewton itself was not chronicled until c12 when the church was given to Kirkdale Abbey in Yorkshire. Was there an Anglo-Saxon church here? Well there are signs of Anglo-Saxon stonework in the chancel and two Saxon coffin lids have been incorporated into the tower so if there was no Saxon church here where did they come from? The plot thickens still further with the church’s greatest treasure: a carving of the Adoration of the Magi now mounted into the chancel arch. It is at least Norman but could be Anglo-Saxon. Excavations have shown that the westward extent of the present c19 chancel also marks the limit of the original church. The chancel on the other hand was 10 feet longer. The building was originally cruciform. There was a known incumbent from 1153 to 1197 so it was presumably Norman. The Church Guide remarks that this would have been an unusually long church chancel compared with the nave. I would add that it would also have been a remarkably long church overall as well. Why did the Normans build something so large? Well this church serves a parish of 40,000 acres - the largest in England - that once contained 15 mediaeval settlements! Well there’s little left today even of the Norman building. The west end of the extended chancel must be at least partly Norman. So too the south chapel. A north aisle added during the Early English period was destroyed at some time and the one we see today dates only from 1856. The nave and south porch were rebuilt at the same time so there is a great deal here that is essentially Victorian. The tower is entirely late c19. Because of its position the church was several periods in which the church was ruined to the extent that the Bishop of Durham authorised the incumbent of 1436 to say mass at any safe place outside the church. It was too dangerous to gather the parishioners in one place! Rebuilding later that century produced the present bunker-like chancel with its thick walls, tunnel vault and small windows. This was an air raid shelter of a chancel! The south chapel is similarly fortified. The Magi sculpture, ironically, shows the Wise Men dressed in what seem to be kilts! The church is only one of 35 dedications in England to St Gregory the Great - the Pope who sent St Augustine to these shores. It is an enigma in many ways. There is much that it difficult to understand and enforced constant rebuilding has blurred a lot. I can’t help feeling that there is much about this place we don’t know. The Magi sculpture is a treasure, albeit a crudely executed one. Go to Kirknewton, though, to sense what it was like to be living on what was to all intents and purposes a frontier village. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

Left: The view west. This is a bright, airy church with rather nice light coloured pews. Note the unusual (Victorian) windows at the end of the nave. The chancel arch hints at an earlier era of architecture. The Magi sculpture is to the left of this arch. Right:The view to the west. This is a high and comparatively narrow chancel. |

|

|

|

The tunnel-like chancel (left) and its deeply-splayed south window (right) that reveals the fortess-like depth of the masonry. This is a foreshortened version of the original chancel. The windows are Early English in style, as are so many in this church, but like the rest the east window cannot be original. |

|

|

The Magi sculpture. There is no escaping it: those Wise Men do wear kilts! We can’t tell which are McMelchior, McBalthasar or McCaspar because the gifts are indistinguishable but it is worth bearing in mind that this sculpture was certainly painted originally. It is certainly crude. Pevsner points to the peculiarly stiff representation of the Virgin holding up her arm to greet the Magi. How old this sculpture is nobody knows. See, however, my footnote |

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

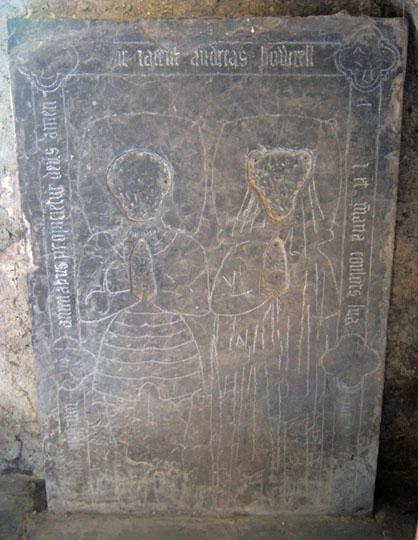

Left: The equally tunnel-like south transept houses the Burrell Chapel. In the right background (behind the mediaeval radiator) is the tombstone of Andreas Burrell and his wife (right). |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

The Anglo Saxon coffin lids set into the north and south walls of the tower. Where did they come from? That to the right is from a woman’s coffin. We can tell this from the shears to the left of the cross. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote - The Magi Sculpture |

|

In a book of 2003 entitled “The Three Holy Kings” by Hugh Mountney* the author suggests that the caps worn by the Wise Men (whom, he reminds us, were actually astrologers) are “Phrygian Caps”. He says that an image of the Magi wearing such caps and “kilts” was found in the Greek Chapel of the Roman catacombs. He suggests that St Paulinus, himself a Roman, may have instructed the sculptor and that it was commissioned for the Anglo-Saxon palace at Yeavering (see above). Of course, if this was correct and the stone was brought to Kirknewton from Yeavering then it would also be possible that the other Anglo-Saxon fragments came from there. There is no certainty about the connections between Kirknewton and Yeavering but you might feel, as I do, that it is inconceivable that there were none. Hugh Mountney’s suggestion certainly sounds plausible. Furthermore, it suggests that the “kilts” were not some kind of early Scottish garb - attractive as the notion is - but simply a copy of an earlier European mode of dress. This would also, of course, confirm the much earlier dating for the sculpture. If it dates from the early c7 then it is a treasure indeed. * pub: Gracewing. ISBN 0-85244-407-9 |