|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

its shallowness invites us to consider the possibility that there was a Norman south aisle too. The arches, however, are also Perpendicular. It has a clerestory that is somewhat squashed between the aisle roof and the eaves of the nave roof. The south side has a typical Suffolk porch decorated with so-called “flushwork”. Suffolk was conspicuously lacking in stone quarries so many of its churches - and its houses - were faced with local flint. Flushwork was an attractive device of using stone frameworks filled in with flint to create attractive decorative designs. The absence of quarry stone, by the way, is generally postulated as the reason that East Anglia has so many round tower churches: there were no large blocks to form the quoin stones at the corners. Huntingfield’s tower, however, is in the normal rectangular style although you can see that its corner buttresses are themselves decorated with flushwork. But you will be here to see, Mrs Holland’s painted extravaganza, won’t you? It attracts respect from historians who feel it does not stray too far from how an original mediaeval paint scheme might have looked. Amongst all of the admiration it is actually quite hard to find out how much of the timber roof itself is original and how much, if any, Mrs Holland commissioned herself. It is quite breathtaking to see. And it is awfully Roman Catholic! That is to say, that full of the iconography that would have been, at best, painted over at the Reformation. It is beautiful but it is not much fun! In the prudish and correct Victorian era Mildred was never going to paint anything as vulgar as a green man, for example. Apostles and angels are everywhere. How one longs for the weighing of souls and the damned being dragged off to the burning pit by slavering demons! It is, in short, a very sanitary schema and to that extent not very mediaeval at all.. Mildred’s aging Granny would have found nothing to take exception to here. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The attractive south porch. Note the restrained but effective use of flushwork for decoration., the honey coloured stone contrasting with the variegated flint. Note also the Madonna and Child in the niche above the arch: a distinct product of the Catholic revival. Centre: Looking east towards the chancel with its Decorated style window. Right: Looking west. To the right are the well-mannered round arches that were surely replacements for the original Norman round-arched arcade. To the left are the later Perpendicular arches of the south aisle. The lofty tower arch is the perfect frame for the octagonal font and its outsized Victorian timber font cover. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

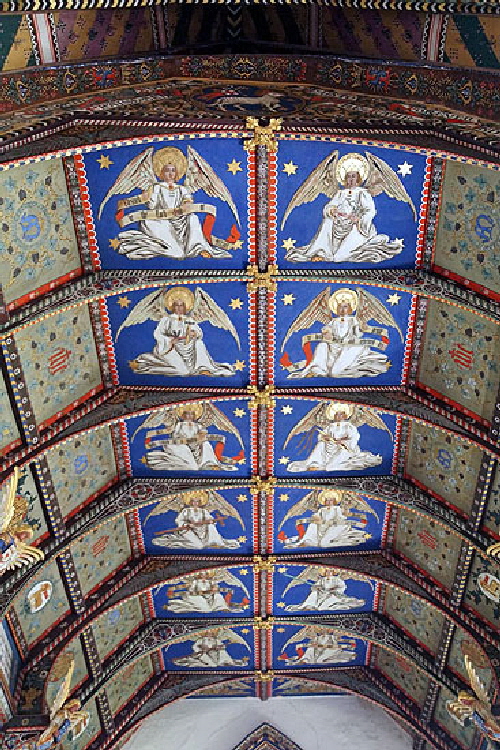

The chancel ceiling. This was the earliest of Mildred Holland’s work. Her husband, the Rector, closed the church for eight months in 1859 to allow her to do it. That tells you quite a lot about the deference that the clergy were used to at that time. Holland, however, himself paid óG1600 of the total cost of just over óG2000. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Mildred has three years off after completing the chancel before embarking on the even bigger task of painting the nave. It was not until 1886 that the church was to be free of scaffolding. Quite what the congregation thought of all this is not, as far as I know, recorded. The angels are surely not mediaeval. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

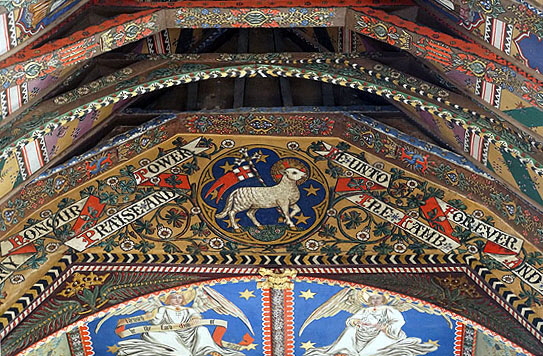

Left: This agnus dei with surrounded by decoration and script adorns the beam that separates the nave from the chancel. Right: This is not part of the ceiling scheme. It is the eagle that tops the extravagant Victorian font cover. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Nave and chancel ceilings. Right Upper: The attractive wooden font cover. There is an a acid test with these things. Is it so big that it needs a pulley system in order for it to be raised and lowered? In this case, as in so many in Suffolk, the answer is yes! Suffolk has a bit of a thing for these extravagances, For one of the best of all see Ufford. It was erected in Mildred’s memory. She lived from 1813-78. The couple married in 1835. William Holland outlived Mildred by thirteen years, marrying again only three years after Mildred’s death before dying himself at the age of seventy eight. Right Lower: The font is octagonal and, at a guess, fifteenth century. Alternate panels are Tudor roses, supporting this possible dating. Two panels have lions (as shown here) and two have angels. It is all supported by four lions, |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The north aisle. The arches have piers rather than columns and the whole thing has clearly been remodelled, although the surviving upper window is testament to Norman provenance. Note the funerary hatchment on the wall. Right: The single surviving Norman window opening, now looking into the north aisle rather than to the outside of the building. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The south aisle. The windows here are rather unimaginative things surely post-dating the aisle itself. Right: Remains of an Anglo-Saxon cross slab incorporated into a wall. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

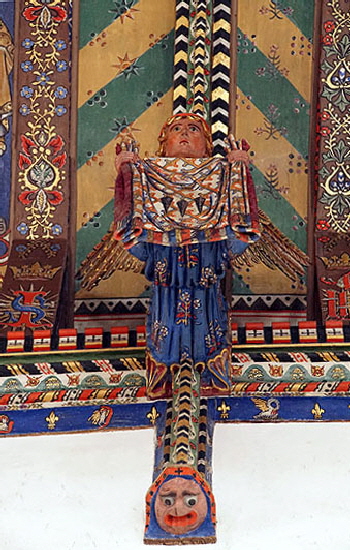

Left and Centre: Having suggested that Mildred was not God’s gift to the world of drollery, it has to be admitted that she showed some sense of fun in painting the bottom parts of these corbels with what might reasonably called grotesque faces. That begs the question whether these were Victorian creations as I suspected or whether they were after all part of the mediaeval ceiling? Right: There are several wall monuments and this one is of 1659. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Having begged a bit of time off from learning to play the harp, this angel decided she need to catch up with a bit of washing. Right: The attractively tiled floor of the chancel. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Centre: As with much in the church, it is hard to distinguish the old from the comparatively new. On the left is a greyhound on a bench that looks quite recent. There is quite a lot of greyhound imagery around the church, giving rise to the idea that “Huntingfield” used to be just that. The figure in the centre with a beast at his feet looks older but still post-Mediaeval. Right: Pevsner did not comment on this brass lectern. They are not, in fact, very common and this one is particularly splendid. Again, though, it is difficult to date and may well be Victorian. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The fifteenth century tower from the west. Centre and Right: As previously noted, Suffolk is not a great area for sculpture but like many Suffolk porches, Huntingfield’s sports a carved pinnacle on either side of its gable. |

|

|

|||||||

|

In typical late Gothic fashion, the porch doorway has decorated spandrels, in this case showing coats of arms. I haven’t been able to establish whose they were. . |

||||||||

|

Footnote - English Eccentrics |

||||||||

|

We English - or is it we British? - have a love affair with eccentric people. To the extent that the word is a noun as well as an adjective. If you are a bit weird your best hope is that you will be labelled “an eccentric” and ipso facto all your oddities are forgiven and you become a treasure. I often wonder if this is true in other countries. I am sure they have eccentrics too but are they the object of mild veneration? Eccentric clergy are a recognised and much-loved subset of the genre. Fortunately or unfortunately, depending on your point of view, incumbency at an English parish church could give an eccentric - or a clergyman’s eccentric (or bored) wife - a degree of latitude perhaps not available in other professions. Like doctors, good clergy can become beloved of their clients. That was the first prerequisite perhaps for using a church as an anvil for the hammer of his eccentricity! The second, it seems to me, is a good income or a wodge of capital to fund one’s self-indulgence. We see this, of course, at Huntingfield where the Rev Holland funded his wife’s somewhat batty idea and his parishioners endured the inconvenience of it all. Nowadays we might applaud Mildred for her determination to do her thing in a male-dominated environment: a break from supporting her husband in the many duties of a rural vicar and his missus. Back then when women were expected to know their place, preferably not too far from the kitchen and nursery, her activities must have caused a local sensation. In fact the notion of “English eccentricity” was probably invented by the Victorians. But sometimes I do wonder if that is true? How much of what we find incomprehensible or bizarre in our parish churches might be attributable eccentrics giving rein to their peculiarities centuries before the Victorians? Anyway, for further examples of clerical barminess, I commend to you the Rev Sabine Baring-Gould at Lewtrenchard in Devon and the Rev Robert Blackburn at Selham in Sussex. I will try to think of a few others.

|

||||||||