|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

Left: The church from the south east. The Norman tower and even its “friendly” broach spire have been invaded by the nave roofline. As we shall see, the Norman roofline was lower than the present one that seems to have been established in the thirteenth century: see the clerestory with EE lancet windows. Note the unusual window in the east end of the nave. It is made possible by the large disparity between the nave and chancel rooflines. That window looks later than the clerestory and probably contemporary with the chancel. Note the extremely shallow Early English south aisle with tiny lancet window, all of this being mirrored on the north side.. The chancel is a fourteenth century rebuilding with window designs of the Decorated style. Right: Looking east along the nave, Note the steeply pitched aisles to either side. There is little of the original Norman fabric to be seen. |

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

Left: The tower from the south. Note the Norman windows and bell openings. I would have expected the broach spire to have been a little later but the way it has been obscured at the east side by the raising of the Early English clerestory suggests otherwise. Note the strange discontinuity in the west wall (that is, the right hand side). It looks like the west wall has been moved slightly east. Yet from within (see picture right) it is clear that the west wall with its Norman arch, old visible old roofline and double Norman biforum is in its original place. The authoritative “Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Herefordshire” published by HMSO on 1931 says this is, in fact, the oldest part of the church. dating from the eleventh century, whereas the rest of the tower is twelfth. So what was on the west end before? The tower arch is too wide to be a west doorway. Was there an earlier tower? And if there was that still doesn’t explain this discontinuity in the church’s external masonry! To quote Pevsner (lest you think I am being obtuse) “No convincing explanation has yet been given to the break at the N and S walls (of the tower) and the set back continuation to the east which makes the tower oblong”. Right: Well, I guess I’ve said most of what needs to be said about the view to the west of the church in the previous caption! That west wall is very Norman indeed. The old roofline shows the extent to which the nave walls were raised to accommodate the aisle arcades and the clerestory. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

Left: The chancel. was rebuilt in the fourteenth century. The east window looks pleasant but undistinguished. As we will see, however, its glass is anything but undistinguished. Right: Looking from the south aisle towards the chancel arch. As you can see, the aisle is narrow by any standards and I was only half-kidding when I said it looks as if it has been designed to be just big enough to house the lancet window you can see at its east end. When you think about it, carving out large arches through the nave walls is a heavy price to pay for the minutest increase in accommodation. Narrow aisles, however, meant steeply-pitched roofs that would have helped clear away the much heavier snowfall of that time - a time when lead for roofs was hard to afford. Perhaps the parish or patron liked the idea of a grander plan for their church or, more likely, they wanted to accommodate the processions that were becoming an increasing part of the liturgy. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

Left: Looking west through the screen to the west end. The south window of the chancel (to the left) also has celebrated glass. Right: The tower arch. It is a very plain affair and suggests that the church never was the haunt of decorative carvings. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The east window is very much a single composition. The glass itself would have been imported, no coloured glass being manufactured in England until the sixteenth century. The predominant colours are green, yellow and brown. Red and blue - which required more expensive pigments - were used sparingly. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Some of the panels in the east window could be described as “iconic”. Close examination shows that the glass has been re-set: in both the mid-nineteenth century and again in 1928. look in particular at the many discontinuities in the designs surrounding the central vignettes. Left: In this delightful composition and very human-looking Mary is having her chin pinched by a rather precocious looking Jesus. The toddler Jesus, I guess you might say. In his left hand Jesus holds a dove. Centre: A crucifixion scene. This is extraordinary, Christ hangs broken on the cross. The artist has made his fingers and - especially - his toes large and conspicuous, the better to display the nails that grotesquely secure him to the cross. His eyes are closed, head hanging to one side. There is no “glory” here. This is a man suffering a slow death by a method calculated to cause the maximum agony and degradation. In a strange counterpoint, The Virgin Mary and St John seem to be staring at Christ’s nailed feet with something resembling thoughtful curiosity! Right: St Michael appears a happy bunny here, busily weighing a soul in his scales. Many of the figures in the glass here have faces with cherubic qualities, like children acting it all out in the school play. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

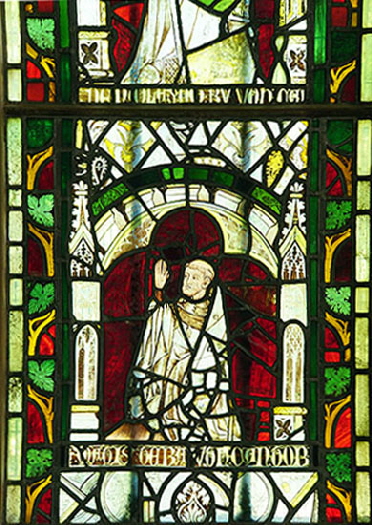

Left: This figure of a priest appears below the crucifixion scene. He is in mass vestments. The inscription is fragmentary and says “John ca”. Centre: This kneeling figure sits below the the priest (left). he is tonsured so presumably he is a monk. Note the Decorated style architectural motifs to either side of him. Right: St Gabriel with a palm in his left hand. Part of his face has been lost bu what is there still shows the kind of pre-rapahaelite serenity seen elsewhere in this window. To his left are representations of Decorated style windows. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The top lights depict architectural canopies. I always find the practice of depicting contemporary architecture in the Decorated period particularly fascinating and endearing. For even better examples see Dennington in Suffolk. Centre: This panel in the right hand light of the east window. It is a face of Christ - see the crucifix halo - but the rest of him has been lost and he has been surrounded by a patchwork of fragments. To the left is a border of fleurs de lys and heraldic lions. Right: The south chancel window is clearly by the same master because, as we shall see, the Christ ganging from his cross is clearly similar to the one in the east window, |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Christ sags on his cross. There is a human pathos about the Christ figures at Eaton Bishop which is far removed from early representations in the first millennium where sculptors could not bring themselves to see Christ as a human figure despite this being a core tenet of Christian faith. Nothing could be more human than this figure, The legs and arms are sinewy allowing us to imagine the stresses of the crucifixion posture on the human frame. The toes seem to be contorted with pain. In this scene Christ is alone with his agony. This might be the most chilling depiction of crucifixion I have seen in an English parish church. You can only wonder at the twisted minds that devised and enacted such punishments. It is extraordinary to think that in the gospel narrative Christ was condemned by his own kind just for not conforming. Nothing changes much, does it? Centre: The kneeling figure of a priest. He holds a scroll saying “Ave Maria” Right: This is probably The Virgin Mary. In effect the glazier is reproducing in three parts (St John will be the next picture) the central motif of the east window. Having said that Mary looked a little thoughtful in the east window crucifixion scene, here she we see a more engaged Mary, her hands perhaps wringing with horror. |

|

|

|

|

Left: St John holding his gospel in the south chancel window. Centre: Looking down the south aisles towards the west end showing, again, the narrow proportions and a width that is almost filled by a single lancet window. Right: The tower from the west. |

|

|||

|

The east nave window.Nobody talks about this much and you can see why. I |

|||

|

The east nave window is largely unremarked. It is Victorian glass dating from only 1895. It is worth comparing it with the mediaeval glass in the chancel. Delicacy here has been replaced by gaudiness. Christ here is resplendent - robed and magnificent. His features are handsome. Nothing could be more removed from the broken man of the chancel glass. He is flanked by two angels - one carrying a spear - that look like Christ’s praetorian guard. The figures at the lower corners are for all the world like courtiers. Somewhat incongruously a couple of soldiers sit asleep on the job. These are the Roman soldiers that customarily sit at the feet of Easter sepulchres (see, for example, Hawton in Nottinghamshire) having a bit of a kip while Christ emerges from his tomb unnoticed by the negligent guards. Quite what they are doing in this composition I don’t really know unless Christ is supposed here to be in the act of resurrection? Either way it is an artless piece, as devoid of emotion as a roll of wallpaper. Bizarrely, the glaziers have tried to reproduce the gothic canopies of the chancel glass. In terms of its execution this is not by any means amongst the worst piece of work. It is by the well-known workshop of Clayton & Bell who were renowned for their technical innovation and the luminosity of their compositions. Their windows are found all over the world and in very prestigious locations. It is the artlessness that I dislike and that’s not, I think, the fault of the glaziers. It reflects a view of Christ that the Victorians loved: all “majesty” and ruling his “Kingdom on Earth” and all that jive. Even the supporting cast look like aristocrats. I’ve always said that if I were to find Christ it would be in a humble farmyard church somewhere not in a big prestigious Palace of God. Anyway, form your own views. I like a bit of a rant sometimes and as a non-believer I acknowledge this is self-indulgent of me! |

|||

|

Click Here to Return to “The World’s Greatest Church Trail III” |

|||