|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The church from the south west. With its fifteenth century tower and gothic windows there is little here to indicate the church’s ancient provenance. Right: The south wall of the chancel, on the hand, screams “Norman” with all its might! In fact all of the south wall is Norman but it is only here with the survival of Norman blind arcading, The stonework that fills the arcading looks modern and doubtless some re-pointing and re-facing has been done at some time but if you look closely you will realise that the horizontal courses of mortar exactly match those on the nook shafts that divide the two bays. Note the use of small horizontally-laid stones to fill the problematic round arches. The rectangular proportion of an original Norman window survives to the right as does the filled-in priest’s door. The polygonal (pentagonal to be precise) apse would have sprung from the east end of this wall and would have had the same blind arcading as we see here. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The Norman south door with its Tree of Life tympanum and zig-zag decoration sits somewhat uncomfortably within the fourteenth century south porch that had to be squeezed in alongside the existing south transept. Centre: The length of the church is immediately apparent from this picture looking towards the east. The conspicuous thickening of the walls (and consequent narrowing of the floor space) indicates the western extent of the original Norman axial tower. To the left and right are large arches giving onto the later later transepts. Right: Looking towards the west. The beginnings of a surviving Norman window can be seen to the left. The west wall was rebuilt in the fourteenth century and the west window that was inserted at that time has been eclipsed by the fifteenth century west tower. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The Tree of Life tympanum. Interestingly, the Church Guide of whose irreverent style I much approve, suggests that this is a somewhat pagan symbol carved by masons who were still Anglo-Saxon in spirit and defiantly asserting their roots. Much as I like this idea, it has to be said that this tympanum post-dates the Conquest by a generation and that the Tree of Life is found in many cultures and religions, not least in Genesis and Revelations! I can’t really, then, endorse the Church Guide’s entertaining suggestion. Looking closely at the decorative coursed we can see that the masons’ competence was somewhat tested by the challenge of producing courses of curved stone Right: The western capital of the south door with its tall profile and simple decoration which is precisely matched on the eastern side. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

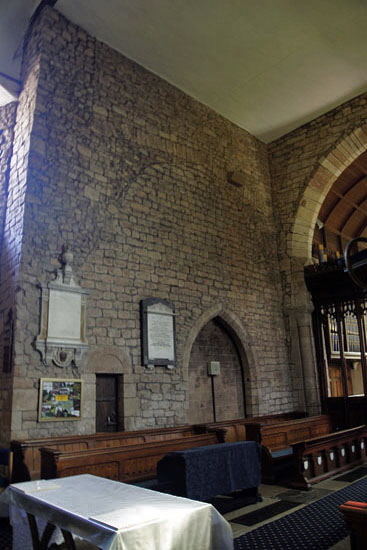

Left: The west wall. I am alone, its seems, in finding this “problematical”. The west wall was rebuilt after the near collapse before the fourteenth century. What then, I wonder was under the arched outline clearly visible in this picture? As far as I can see it must follow the ceiling profile of that time prior to the addition of the west tower? It can’t be the roof profile.because the arched profile does not reach as far as the nave walls. Centre: This would have been the north wall of the axial tower of the Norman church. I confess it is a total mystery to me. I have tried in vain to find an explanation for the conspicuous course of vertical stones set in a shallow vee-shape near the top of the wall. below that a large area seems to have been in-filled with stone that does not match that which it surrounds. What are we missing here? Note the little doorway at the bottom left which is believed to have given access to an external stairway that in turn gave access to a rood screen. Right: The stairway door. The plain tympanum is monolithic set within massive jamb stones. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The chancel. The east window is a nineteenth century reconstruction in Perpendicular. Its glass is by Kempe and therefore a cut above the usual Victorian trash! Right: The south wall. Note the deeply-splayed Norman window - the exterior view an be seen below.. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The south nave Norman window. The little “capitals” are in both dimensions and simple stylised decoration very typical of the Dymock School. Note the decorated string course. Centre: I am a sucker for these cobbled together collections of mediaeval window glass fragments! Right: The porch is fourteenth century. The nave wall in the background shows three pilaster strips as well as short length of the Norman string course (see below) that extends over quite a length of the south side. Pilaster strips are normally associated with pre-Conquest churches. Taylor & Taylor observed : “These are not certainly not normal Norman buttresses but; nor indeed are they normal Anglo-Saxon pilaster strips; but their affinities are more to the Anglo-Saxon type...” This reinforces the vaguely unsettling notion that nobody really knows what happened here at Dymock Church, |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A length of Norman string course. The electrical flex is modern. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The church from the north. You know, it’s funny. This might or might not have been called the “Devils Side” by mediaeval parishioners. Personally, as I have said elsewhere, I believe that the belief was probably deep and enduring in rural areas. I don’t know what the view was amongst Dymock-ites. The existence of a north porch seems to indicate that the belief did not hold sway here. There’s no denying it, though. It’s darned difficult to ever get really nice pictures of north sides of churches! There’s little light and a lot of moss! Evidence of the Norman church is sparse on this side. Right: It is worth looking closely at the edge of the tympanum. When you look at the rather disordered masonry to its left it is easy to see why most experts agree that the tympanum was “let in” some time after the doorway itself constructed. It begs many questions, not least what was there before? Why the sudden need? How long after the doorway was constructed was the tympanum installed? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Click Here to Return to “The World’s Greatest Church Trail II” |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||