|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Dedication : St John the Baptist Simon Jenkins: ***** Principal Features: Superb English Wool Church; Fascinating Monuments |

||

|

|

|

Anglo-Saxon and may have been incorporated from a pre-Conquest stone church. Intriguingly, there is also a sculpture that could be Roman, Saxon or Norman! The Norman church, probably of about 1175, was a simple through building of nave and chancel with an axial tower. It is worth noting that the nave was never extended, as evidenced by the original Norman west door. The chancel was probably apsidal at that time. During the course of the thirteenth century the church acquired first a south and then a north transept, so that it was now cruciform. The chancel was extended and changed to a rectangular shape. The richer townspeople built their own “Chapel of Blessed Mary” - a lady chapel - by the middle of the thirteenth century. Unusually, this was very close but separate from the church to its south west. Possibly the Guild wished to declare their ownership of the chapel through this separation from the main church. In any event it was incorporated into the church during the fifteenth century. Having not been built on a west-east axis it gives the south side of the church its rather odd floor plan. To incorporate it at all the masons had to extend it towards the east whilst shortening it to the west. All of this gives the west end of the church a most bizarre look. Before that, however, there was a raft of other additions. First of all a chapel was inserted between the south porch and the south transept, sponsored by the Guild of Burgesses. It was dedicated, somewhat unusually, to St Thomas a Becket. The Church Guide offers an explanation that he was the patron saint of Thomas Spicer, a senior man in the Guild. It is my guess that this dedication was put into abeyance during the days of Henry VIII who - quite reasonably when you thing about it - saw Becket as epitomising the efforts of the Church to challenge the rule of the monarch which, of course anathema to a man who saw himself as head of state and church. Few memorials or statues commemorating Becket survived Good King Hal. This chapel, for no apparently good reason has its outer face that is not quite parallel to the church. It begs the question whether its line was altered when the Lady Chapel was joined to the rest of the church. This chapel dwarfed the adjacent south porch which at this time was far from the lofty proportions it was later to assume. The fifteenth century, as we have seen, saw the joining of the Lady Chapel to the main building, By now, however, the wealthy burgers of Burford were really hitting their stride. First, a stage was added to the tower around the start of the century. The nave was rebuilt with aisles and a clerestory. St Katherine’s Chapel was then built to flank the chancel to the north, and Holy Trinity to the south. The south porch is one of the finest in England. This being Burford, a two-story chapel was not enough and so the parish funded one with three storeys. It is also fan-vaulted that most extravagant manifestation of Perpendicular architecture and rarely seen in a parish church. From the evidence of the carved heraldry, the Church Guide asserts that the porch dates from the latter half of the fifteenth century. Finally, within the body of the church is St Peter’s Chapel. It is surely a rare surviving separate chantry chapel (as opposed to one located in an aisle) such as that at Boxgrove Priory in Sussex. Its function could not survive the Reformation, however, and it was re-dedicated to St Peter. This is a church that merits a much longer description than I have either the time or knowledge to give. Unsurprisingly, it has lavish literature that visitors can buy. Apart from its architectural interest, perhaps its main value is in demonstrating the amount of largesse that a town of prosperous merchants was willing to lavish upon its church. The floorplan shows that at its peak the church had eight altars and doubtless a body of clergy sufficient to serve them. For the nouveaux riches of Burford this was how they demonstrated their wealth and their generosity, in part of course to speed themselves and their families through Purgatory. If you were not one of the biggest cheeses in the town but a person of substance and standing you could become a member of a craft or town guild and show your worth through the collective. The outcome of all of this is a church that is, to be sure, magnificent but which also, as is so often the case with richly-endowed churches, made somewhat incoherent through its constant extensions and modifications. That, of course, is to quibble. What we have is sufficient to gladden the heart of any church crawler. Is it one of the top twenty parish churches in England? I am keeping my own counsel! |

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

Left: Another view of the south side. Note the assortment of Perpendicular style windows. Norman windows peep out from the tower. Right: The north west of the church with a similar array of windows. |

||||||||

|

|

|

||||||

|

Left: The magnificent - and hubristic - three storey porch of about 1450. Centre: It is easy to tell where the Norman sections of the tower begin and end. The louvred bell openings have ornate ogee arches in Burford’s usual grand style. Right: The west window and doorway of the Lady Chapel at the south west of the church. To the right, forming the extreme south west corner of the church, is an octagonal stair turret leading to a doorway that gives our onto the chapel roof. All of this is the product of the joining of the once-separate Lady Chapel - or “Merchants Guild Chapel” in the fifteenth century and the architectural style - the large radius Perpendicular window and the rectangular doorway - reflects that. The stair turret is an oddity, however, and a further demonstration that money was no object here. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The top of the south porch. I have to presume that the niche statues are replacements for the originals would surely not have survived the Reformation. The eight prominent decorations either side of the Virgin are somewhat weathered faces of angels clutching shields. The elaborate cusped blind arcading shows this all to be the work of very accomplished masons. Right: The most obvious remnant of the Norman church other than the tower is the west door of the nave. Pevsner dated the original Norman church to 1160 citing the design of the arches on the tower; whereas the Church Guide prefers 1175. Fifteen years is neither here nor there, you may feel, but for what it is worth the course of beakhead moulding makes me prefer Pevsner’s view. It tells you something about the microscopic study of Romanesque architecture that commentators feel able to essay such precise dating. Much of this church was built two and three hundred years later but without written records we would be unable to debate its dating so finely. Note on the door itself the very attractive iron hinges. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the east of the church to the crossing and the chancel. The fifteenth century aisles have symmetrical arcades. The original Norman roofline can clearly be seen. This picture gives you some idea of the challenges posed to modern congregations by cruciform churches. The high altar looks a very long way off with a lot of space wasted under the crossing. This would have been much less troublesome in mediaeval times where screens would have made much of what was going on around the altar invisible to the congregation by design. Allowing for the fact that these pictures were taken in 2020 not long after the height of the Covid-19 epidemic when things were hardly normal, you can see how the church has chosen to arrange its seating around the pulpit to the left. This is, perhaps, another endorsement for the concept of flexible seating within churches today - where, I hasten to add, the original seating is not of artistic or historical interest. To the right of the nave arch you can see a stair tower. Set the foot of that is a doorway with a plain tympanum and a distinctly pre-Norman look to it. Is it a recovery from an earlier church? Centre: Looking out from under the crossing and its Norman arch to the west end. The crossing space has been utilised for, amongst other things, a spinner for leaflets and postcards! Right: The Norman central tower. A spire weighing 700 tons was added in the fifteenth century on top of the additional tower stage. In a far from unusual occurrence, the added weight put enormous strain on the Norman arches that had to support a weight far beyond that for which it was designed. The masons probably had little idea of how deep the Norman footings were or what material had been used. Of course, this weight would have been transferred by the arches to the surrounding walls and the whole lot was in danger of collapse. The masons were forced to fill in the transept arches and leave much narrower openings. The north transept was severely shortened, accounting for its lack of symmetry with its southern counterpart. In this picture you can see there is still some sag in the masonry and that some of the Norman window spaces have been filled in. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I was indebted to the Church Guide (the human being, not the book) for pointing out to me two little capital carvings high up on the tower balustrades. You are not going to see them without binoculars or a zoom lens. Left: A typical Norman green man or cat mask. To the left is a VV carving that very obviously by a mason. It looks like a mason’s mark that I know will excite some of you! Right: A monster draped around another capital with bodies either side of the central grotesque head. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The crossing has an internal bell turret at its south west corner (see above). High on its south wall is this carved stone which is Burford’s little mystery. One theory is that it is the Celtic Goddess Epona (“divine horse”) and that it dates from the Roman era. Another has it as the flight into Egypt showing Mary and Joseph walking with Jesus who is astride a donkey. I don’t know how you could ever reconcile these conflicting claims and they could both be nonsense. My only contribution is to suggest that the Holy Family would have been unlikely to have been portrayed without any nimbs (halos) or signs of the cross. Right: Something colourful for a change. This is the lovely ceiling of St Peter’s Chapel with Peter’s keys much in evidence.. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

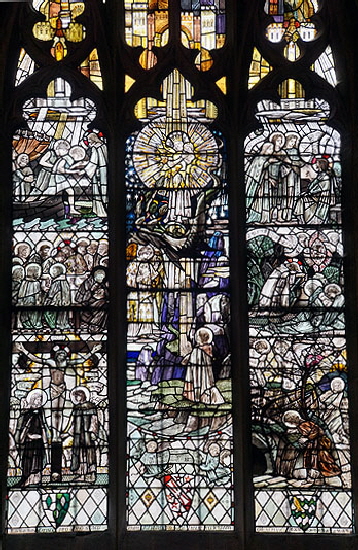

Left: St Peter’s Chapel. It is a very pretty addition to the church. The Church Guide believes it was originally dedicated to the Holy Rood. It was surely, however, a chantry chapel. And if so, one wonders who endowed it? In a town full of wealth a man must have been a very big cheese indeed for it to be a family dedication. More likely, perhaps, it was provided by another town guild? What is known is that after the Reformation it became the family pew of the lord of the manor between 1580 and 1875 and was rededicated to St Peter after the church’s 1870 restoration. Centre: The altar and reredos. If the chapel survived the Reformation through change of us, how did these figures survive? Are they replacements? Right: the south transept window glass is by the famous Christopher Whall. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This stone ceiling is over the altar of St Peter’s Chapel. It seems that the chapel originally comprised might have comprised just this east end. It is surrounded by wooden parclose screens built from screens dismantled at the Reformation. Right: The view from the south west of the church to the east through the Lady Chapel. The chapel is a very large space indeed as the fifty or so seats here show. One cannot help thinking that for most of the time it has been added to the body of the church it might have been a mixed blessing! Architecturally, it is a real oddity. Note in the foreground the chapel arcade and beyond that the south aisle arcade. The chapel is something like three times the width of the aisle itself as well as extending several feet west of the nave, overshadowing the west end itself. The window to the left of the east end is from the adjacent porch. Through the right hand arch you can see St Peter’s Chapel surrounded by its reclaimed wooden screens. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The reredos of the Lady Chapel. It dates from 1911 and was by E.B.Haore Right: Two Early English lancet windows. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

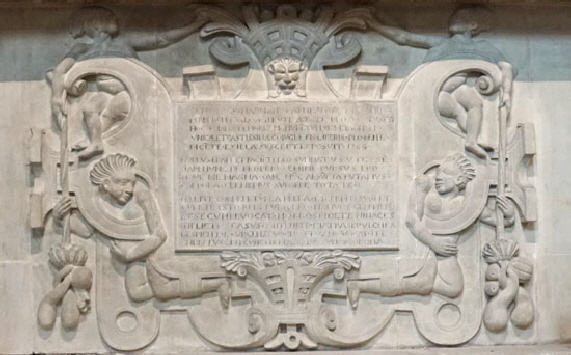

Left: The seventeenth century effigies of Sir Lawrence and Lady Tanfield. Tanfield (d.1625) was Chancellor to James I and his grandiose mausoleum fills St Katharine’s Chapel on the north side. This pair were reviled in the town for centuries after their death. They enclosed land, gouged their tenants and were both corrupt, Lawrence being a judge on the King’s Bench. On Lawrence’s death his wife more or less commandeered the chapel but joined her husband not long afterwards. Right: * It is a cadaver tomb that has a skeleton effigy at ground level that was, as the Church Guide suggests, something of a throwback to earlier times when acknowledgement graphic demonstrations of the inevitability of mortality was all the rage. This is a particularly anatomically plausible specimen! |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The Tanfield memorial. Centre: This chubby little figure is Elizabeth Tanfield, the only child of the marriage. This is a wonderful gift to students of costume. Lady Elizabeth was Lawrence’s daughter by his first marriage. She married Sir Henry Cary who became Lord Deputy of Ireland. The Church Guide says she converted to Catholicism in 1626 and was thus estranged from her father - who disinherited her in favour of her son - and her husband. In fact, it was 1625 since Tanfield was dead in 1626 when she announced it publicly. Her husband tried to divorce her but failed. Her children were pushed around hither and yon but ended up at the home of the eldest sibling Lucius Cary who had inherited from Tanfield. That was not before she had had to attended the Star Chamber Court charged with kidnapping her two other sons. Interestingly, the eventual destination of her children was by order of Charles I. Elizabeth was now an intimate of his Roman Catholic Queen Henrietta Maria so this may be an example of the difficult course he steered between his Protestant realm and his Roman Catholic wife. Elizabeth had always been an avid reader and she went on to publish poetry and was England’s first woman playwright. She died in 1639 and was buried in Henrietta Maria’s chapel. This, one feels, is a life that is the stuff of historical novels! Right: * The skeleton stares up at the reclining Tanfields! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

* Photographs courtesy of Bonnie Killingback. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Lucius Cary, Elizabeth Tanfield’s son, who was the recipient of his grandfather’s estate. He seems to have inherited his mother’s literary and intellectual qualities, was regarded as a brilliant young man and moved within circles habituated by the likes of Ben Jonson. He became a soldier and during the English Civil War fought for the Royalist cause. It seems, though, that he despaired of both sides and although he could not support parliamentary government he became reckless with his life. He died at the Battle of Newbury on 20th September 1643. His pet duck, Tilly, is next to him. Right: Female offspring depicted on the tomb in the north aisle of Edmund Harman (d.1569) and his wife (see below). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The Harman monument. Unusually, it has no images of the deceased, only of their sixteen (!) children. Edmund Harman’s is a fascinating story. Raised in Ipswich, he came to be one of three barber-surgeons that attended King Henry VIII in a personal capacity. There were only fifteen such men at any one time and the barbers who attended to the King with a cut-throat razor were in a position of particular trust. Harman was well-rewarded via salaries and gifts of land. He even witnessed Henry’s will and was left the not inconsiderable legacy of £133 (200 Marks) in that will. All this stopped when Henry was succeeded by Edward VI who, as a nine-year-old, had no need of barbers! Itis a story almost as remarkable as that off Elizabeth Tanfield. See also below. Remarkably, we know what Harman looked like because he and his fellow barbers were recorded in a painting by Holbein - see the footnote below. Centre: The chancel. The east window is fifteenth century. the statues occupying the niches on either side of the altar are, of course, modern. Right: The font. Pevsner suggests plausibly that it started life as a Norman tub font - see the base - and was re-carved in the fourteenth century. This is born out by the very Gothic carved arcading. Yet the figure carving is strangely crude and unsophisticated. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: We haven’t quite finished with the Harman monument yet! We can see here the depiction of tribal Indians. No they are not “Native-Americans”, so get down off your high horse! These are South American Indians and all the more remarkable for that. In fact, a Portugese academic has even identified them as being specifically of the Tupinamba cannibal tribe of the sixteenth century from the mouth of the Amazon. Moreover, the beast’s head at the top of the sculpture is believed to be that of a jaguar! Nobody knows for certain what this is about. Perhaps he invested in the earliest trade with the Americas? Or, as also been suggested, the carver who was probably a Dutchman, one Cornelis Bros, may have copied it from an other monument he had seen. For once, the more pleasing notion that Harman had involvement in trade with the Americas seems to me to be the more plausible one. Either way, this is one of England’s earliest depictions of American Indians. Right: The font with Christ crucified. He has been comprehensively defaced but Mary and St John to his left and right have fared better. The whole font shows signs of severe weathering. The Church Guide does not say so but I rather suspect that this font has, like so many of its companions, served time as a horse trough or was chucked in the churchyard to be replaced by something more in keeping with the sensibilities of later generations. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Right: Panels of the font depicting the apostles. St Catherine is easily discernible by her ever-present wheel. A heavily-bearded Andrew adorns stands defiantly on his saltire cross. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Three fine spandrel carvings. Left: It is difficult to believe this is anything other than a merchant who contributed to the financing of the church building. Centre: An eagle with a crown. I thought it should be easy to find out what this represents but, surprisingly, I am flummoxed. St John is usually represented by an eagle but not with a crown. Right: This is actually a nineteenth century carving of the Rev W.A.Cass. It was put there after a mason had accidentally damaged it during restoration work! The man wears a biretta and it is no coincidence that Cass was a fervent Anglo-Catholic. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The lovely pulpit was put together by Street from screen panels from within the church. Centre: This view along the north aisle does give a flavour of the somewhat chaotic nature of the church. The extravagance of the Lady Chapel is to the left. The aisle arches are lofty and almost fill the entire space contrsating with the squat archway to the south transept visible in the background. The tower stairway intrudes into the aisle space. In a more twenty-first century form of chaos there are chairs all over the place! Right: This blocked round-headed north doorway is another little reminded of the church’s Norman origins, |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The top lights of Whall’s south west transept window depicting the New Jerusalem. It is interesting that there is a rather discontinuous look to it and i wonder if Whall was trying to pay homage to the many montages of mediaeval glass fragments to be seen around the country. Right: No Cotswold churchyard would be complete without its quota of “bale tombs” that recorded wool bales as the source of the wealth of those who enriched the town and the church. These are on the south west side of the church with the Lady Chapel to the left. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote 1 - Holbein and Edmund Harman |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Guild of Barber Surgeons still exists and these words are taken from their website: “(the picture) shows the King celebrating the Act of Union between the Company of Barbers and the Guild or Fellowship of Surgeons in 1540. Whilst it was commissioned to celebrate this Act of Union, it was probably painted in 1542 and has remained in the possession of the Company ever since. In the picture the King sits on a throne wearing State robes and the Order of the Garter and holding the Sword of State. He is depicted handing a Charter with the Great Seal to Thomas Vicary in the presence of his surgeons and barbers on his left and his physicians and apothecary on his right, the majority named. The Charter and Seal are artist’s licence as the union was established by Act of Parliament. In the foreground is a Turkey carpet on rush matting and in the background a floral tapestry wall hanging on which is superimposed a cartouche containing a Latin inscription” Those pictured are conveniently named and Edmund Harman is the fourth figure to the right of the King. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote 2 - Burford and William Morris |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Morris, of course, is synonymous with the Arts and Crafts Movement. I love Arts & Crafts houses - and churches - myself but it is pretty hard to see how the exquisite craftsmanship of the movement could ever be translated into the humdrum impoverished lives of the ordinary people in the way that he and his cronies craved. Morris was appalled when he visited Burford Church in the middle of Street’s restorations in the 1870s. When taken to task the vicar - the same Rev Cass shown in the spandrel carving above - memorably replied “The church, sir, is mine and if I choose to I shall stand on my head in it”. Incensed, Morris went off and formed the Society for the Preservation of Ancient Buildings” (SPAB). The society even visited the church for its centenary! The society became known as the Anti-Scrape Society for its strident objections to the removal of plaster from church walls, on the unassailable grounds that with it went a lot of mediaeval wall painting and also a lot of light in the church. They also objected to the removal of low-pitched mediaeval ceilings of traditional construction with high-pitched roofs. Morris’s protests were too late to save Burford’s chancel roof but he did save the nave. G.E.Street is regarded as one of the more reputable and sympathetic Victorian restorers and you can see above that his pulpit at Burford is a thing of beauty. Gilbert Scott pere et fils are also celebrated. I would say that some of their church work was monstrous. Yet some was sublime. I am a frequent visitor to Cumbria and some of the Victorian churches there are simply dreadful. Against that yardstick Street and the Gilbert-Scotts were paragons of architectural good taste, Morris was probably an interfering and self-important fusspot but with some Victorian church architecture he had a point and perhaps we might wish there was more than one of him. A final thought. We might enjoy Cass’s rejoinder. What, though, are we to make of his attitude? It was his church and he would do what he liked with it! Seven hundred years of architecture were his to dispose of as he pleased in Rev Cass’s mind. It is a mindset, sadly, not a million miles from that held by today’s Church of England and its wretched leader. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||