|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

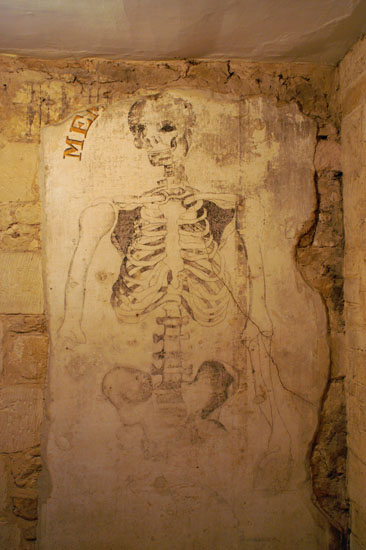

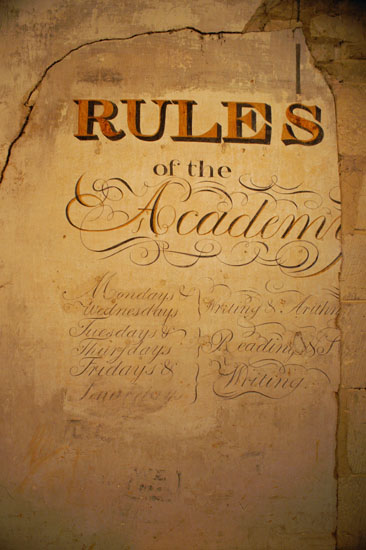

The North transept is mainly Norman, although the aisle is c14. The tower was rebuilt in 1700, following the collapse of the original one. We can see transitional influences on the south side: the porch doorway has restrained decorative courses but with a complex inner design where two courses of chevron moulding are set at right angles to each other. Inside the porch each side is lined with blind arcading that is finer than would be found in a pure Norman church and with inset trefoil mouldings that preview the Early English style. The inside of the south door to the chancel has a distinctly un-Norman course of ball flower mouldings that, as with the south door, has serpent heads at its ends. This church does not have the riot of semi-pagan carvings that can be boasted by the much smaller contemporary churches at, say, Iffley and Barfreston, although there are some; for example on the chancel arch capitals. What we do see is the greater sophistication of the monastic church built, no doubt, by more avant garde (and more expensive) architects familiar with the emerging changes in architectural fashion. Finally, the parclose room above the porch is a treasure house in itself. It is possible to touch largely intact Norman corbels that would have been on the outside of the chancel wall before the room was joined to the wall in c15. It was used as a schoolhouse and an eccentric schoolmaster named Sperry from the early c19 has left a curious legacy of self-drawn murals. As they say, this is almost worth the entry fee on its own! |

|

|

||||||||

|

|||||

|

|

||||

|

The west doorway does, however, have these fine serpents on the ends of the decorative courses. In time-honoured fashion, the one on the south side (left) is determined to eat itself, whilst the one on the north side (centre and right) is content to show off his spectacularly vicious teeth! |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

||

|

Left: The south door demonstrates again the “norm” at Bishops Cleeve of geometric decoration embellished by a restrained use of monsters and serpents on the outermost course. There is a distinctly “Scandinavian” look to these images. Unlike on the west door, however, the serpents on the south door have bodies that link together and form the hood mould. Right: Transitional blind arcading lines both side walls of the porch - whilst making convenient niches for notice boards! |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Centre: These are the monster heads on the inside of the south door. The heads, especially on the left, are ornate and have horns. Both heads look distinctly elongated until one realises that both are in fact consuming the heads of two other creatures. Right: On the south side of the chancel is this Decorated priest’s door which provides an interesting comparison to the transitional doorways shown above. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The capitals on the left side of the porch doorway has this somewhat restrained green man image. Note in the backgrounds to both pictures the beaked heads being consumed by the monsters at the ends of the mouldings. The capitals to the right are sophisticated foliate designs. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The porch has a ribbed and vaulted ceiling. The view to the east end. Right: The Norman piers of the arcades are massive with simple capitals. However, each aisle has three bays only where there were originally six. This rebuilding occurred in the c16 or c17 in order to free up space in the church. Note to left and right of the chancel arch the Norman doorways to the original transepts. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The inner south door continues the Bishops Cleeve practice of ending the hood moulds with - in this case rather small - monster heads. Surrounding them can be see simple ball designs that are distinctly un-Norman but do not have the sophistication of the ball flower designs to emerge in the Gothic period. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The north arcade and aisle. The unnaturally wide arches caused by the reduction in the number of bays are obvious to see. The north aisle is c14 with windows of the Decorated period. Right: The south aisle has similarly wide arches, but beyond the arcade can be seen the south chantry chapel which was added in c14 and is separated from the rest of the arcade by a rather elegant Gothic arcade. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Foliage design on one of the arcade capitals. To me the design is too small for such a mighty structure. Right: The c17 tomb of Richard and Margaret de Vere in the south chantry chapel. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The chancel dates from about 1310 and is of the Decorated period. It is a somewhat austere space that does little justice to the rest of the church. The east window has unusual tracery that would be splendid if it were original - but sadly it is a c19 replacement. Right: Bishop’s Cleeve, like many churches, has some fragments of the painting that would once have covered the entire interior. This example is in a blocked Norman window in the south transept. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Capitals on the north side of the door to the Norman north transept. Right: At the west end is a c17 Jacobean gallery of carved oak. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Both transepts have Transitional doorways either side of the chancel arch. This is the northern one. Right: View towards the west end. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A Norman pillar piscina is built into a recess in the south transept - although this was not its original position. The sharp-eyed reader will have noticed the ogee (S-shaped) arch in the niche above which confirms this to be of the High Gothic period. For my money, that pillar looks a bit suspicious too! Centre: This stone is believed to have been part of the original north aisle and therefore Norman. The words are “me jesu”, presumably left by a mason. Right: Looking to the west end of the south aisle with the gallery to the right and the south door to the left. |

|

|

Close up of the centre of the south door showing the intertwining of the tails of the crocodile-toothed monsters (pictures above) |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I am indebted to Ann Jessop for pointing out that I hadn’t noticed the ancient stairway that leads from the north transept to the bell ringing chamber. The upper portion (left) is cut from solid oak logs. This picture is looking downwards from the top. The lower section is of stone (right). The rail of the wooden section is of one continuous piece of elm and is filled in with wooden panels. |

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

The Parvise Room |

|||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|