|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

St Mary’s Lets begin with St Mary’s. The present church was begun in about 1100 and its glory is its tower. The base and the second, octagonal, stage date from the church’s foundation. The third stage has sixteen sides and dates from the c13 in Early English style with tell-tale lancet windows. The topmost decoration of forty eight blind arches is modern as is the rather incongruous needle spire. There is a Perpendicular style western porch sometimes known as a Galillee. Such towers were known as lantern towers and Pevsner remarks that it is a thrill to discover there was a lantern tower in the county that pre-dates the one at Ely Cathedral. The tower arch is hefty but plain. We have to presume that the present arcade walls up to the level of the clerestory were once the external walls of the Norman nave. Blocked round-headed windows within the chancel show that this too was Norman in origin. The aisles and tall arcades are c15 and are with castellated capitals typical of the High Gothic period. The Church Guide notes that this part of the church is badly weathered because the nave roof was damaged in 1802 and not repaired for a century. The south aisle and south side of the clerestory were completely rebuilt. The south aisle houses the Tothill Chapel, dedicated now as the Lady Chapel. The north aisle houses the Waters Chapel. Both have fine brasses from the Tothill and Waters families. Finally, there is a rather extraordinary set of stained glass in the north aisle that commemorates the First World War. tanks, aircraft, submarines and so on are very realistically portrayed interspersed with what the Church Guide calls “apt yet curiously inappropriate biblical texts”. They seem to admonish the participants rather than commemorate the fallen. |

|

|

||||||||

|

Left: The tower with is three stages, the lowest two Norman and note those raised pieces at each corner. Right: This is an unusual view indeed of the interior of a church tower, Normally our view would be obstructed by the bell-ringing floor but at St Mary’s we are able to get a perspective of the way in this extraordinary tower was put together. Arched “squinches” were used as a device to increase the tower’s plan from four to eight sides. Remember those raised pieces at each corner of the exterior? See how they form the squinches to the left and right of the lower window. |

|||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

Left: The second stage of the Norman part of the tower. The two stages are separated by a course of billet moulding. The window opening is simple and appears quite late. Note the subtle change in the colour of the mortar between the two stages. I find myself wondering whether that the second stage might have been added some time after the first, albeit still within the Norman period. Right: The church from the south east. Apart from the tower, the church has little to distinguish it. It is the most “regular” of churches with the windows all very much of a type and all very simple. Note that the masonry of the south wall and clerestory differs slightly from that of the chancel and the east faces. This is attributable to the rescue work at the turn of the 19th and 20th century. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the east. There is a rood screen complete with rood and this must be modern. It is a poor substitute for the long-lost original. junction. The arcade arches are each surrounded by a continuous masonry course which has the effect of creating a rather streamlined look that is pleasing to the eye. Right: Looking towards the west. The tower arch is Norman and surprisingly large. Note the weathered castellated arcade capitals, graphically illustrating the way this interior was exposed to the elements before its restoration. Note also the string course at the junction between the nave and the clerestory denoting the height of the original Norman external walls. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The chancel with it simple Perpendicular style window. To left and right is evidence of the original round-headed Norman chancel window. Right: A arcade capital. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Funerary Brasses of Mary’s Church |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The plain-as-pikestaff c13 font bowl mounted on a modern pedestal. Centre: One of two mediaeval faces scratched into the nave wall near the tower arch. Right: Grotesque carving on the east corner of the south aisle. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

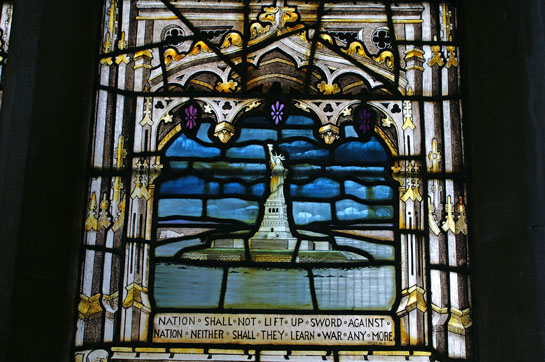

The First World War Memorial Window |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This really is a most unusual composition. There are very realistic portrayals of many aspects of the First World War. We see an early tank, a zeppelin airship, a submarine and an aircraft, amongst other things. We can be sure that there is no intention at glorification of the allied “victory”: the aircraft has German markings and zeppelins were German weapons. Two submarines are shown (lower left picture). The topmost one seems to have an unfeasible row of portholes along its length - more “Nautilus” than U-boat! In the second depiction, the sub is negotiating anti-submarine nets while a surface ship steams above it. I had thought that in the panel to the right of it the same ship is now sinking, but in fact this ship has more funnels and below it there are depictions of mines. There is almost a documentary feel about this window. Accompanying the pictures are anti-war texts taken from scriptures. Whereas most war memorials are in the spirit of sorrow or even triumphalism, this window seems more in the spirit of “look what you’ve done”! Rather oddly, there is also a very detailed picture of the Statue of Liberty (upper right picture). What could be the intention here? |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Left: St Cyriac’s from the north. Right: Detail from the Perpendicular style tower. |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the east end. Right: The west end with its minstrel’s gallery. |

|||||||||||||

|

Looking at St Cyriac’s today, the judgement of Lawrence Fisher was surely too harsh. There is an elegant simplicity here that is not displeasing although its interior does seem to be more reminiscent of a nonconformist chapel than of an Anglican church. Perhaps this was the real objection? |

|||||||||||||