|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

a pre-Conquest wooden structure. The existence of the Saxon churchyard crosses bespeaks of earlier Christian activity in the vicinity but nothing substantial is known. The first stone church was Norman. It was destroyed by fire sometime in the thirteenth century and only a few fragments of it remain. The replacement church was built in Transitional and Early English styles in around 1220. The chancel arch is a very plain, lofty and rather elegant. The church was given north and south aisles. The north arcade is supported by circular pillars whereas the south side has octagonal pillars. They are narrow aisles with steep roof pitches and look to have never been extended laterally. The west tower was not added until 1440. The masonry on the aisles suggest that each aisle was extended slightly westwards at the same time. The east face of the tower shows an earlier, higher roofline. It is not at all clear when the clerestory was built. Its rectangular windows look a little earlier than those on the aisle walls. I suspect the aisle windows were replaced at some time. Bizarrely, the north side sports two outsized dormer windows that intrude into the line of the clerestory windows. With their rendered sides they are, to steal a phrase from Prince Charles, “carbuncles”. It’s another example of something where you look, scratch your head and say “Did nobody dare point out what a bad idea that was?” The misericords are worth travelling to see. Pevsner calls them “one of the most rewarding sets in the country”. In the best traditions of this art form, they combine satirical scenes of domestic mediaeval life with the fantastic. Misericords were for monks whose rheumatic limbs had to endure eight masses per day - see my footnote below. Parish clergy did not have to endure this so when you see misericords in a parish church you can be sure that it had been a monastic church or else had acquired them from a disestablished monastery. The latter was the case in Whalley where the monastery was suppressed in 1536. Sadly, the “collection” was broken up. Apart from those in Whalley, eight were sold to the church that is now Blackburn Cathedral. Two more were acquired by Cliviger Church in 1868 when Whalley’s misericords were “rearranged”. I would like to tell you that these were nothing special but they are and so we have been denied a really thrilling set of misericords in a single location. That said, Simon Jenkins was still moved to say “The church could qualify as a museum of ecclesiastical seating” . The misericords and stalls are known to have been carved between 1418 and 1434 because the abbot’s stall is initialled “W.W.” A visit to Whalley is very rewarding. The church and its churchyard are full of interest and the remains of the Abbey - quite substantial remains for once - are adjacent and managed by Heritage England. I arrived on a Sunday morning just after the 11.00 service was over so access was straightforward. You should check opening on advance, however. The post-service atmosphere in this church, by the way, was very vibrant. A not inconsiderable congregation was swilling cups of tea and having a good old chinwag. We were made very welcome but I’m afraid my pictures are not as comprehensive as I like them to be! |

|

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

The drab exterior gives no clues to thr spacious and bright interior. Left: Looking from the choir - and for once this is a parish church that can lay genuine claim to having one - through the Early English chancel to the west end. Centre: Looking from the east end of the nave into the chancel. The chancel arch is a masterpiece of simplicity, a total break from the Romanesque style that had prevailed only couple of decades earlier. It is of huge open proportions, barely pointed at all, but devoid of capitals or decoration. Take a look at some of the great Norman churches shown on this site - Kilpeck, Elkstone or Devizes - and reflect on what a massive change this was. Those churches were intimate. Their low, rounded arches gave way to tiny secretive chancels beyond where the “mysteries” of the Eucharist were meant to remain mysterious. Early English architecture was the “minimalist” period in English parish architecture. To be sure, then as now, a screen would have given the priesthood its proper distance from the common herd but nevertheless churches like Whalley, perhaps unconsciously, began the process of bringing Christianity into the light of day. The rood screen is fifteenth century and “survived” the Reformation. The rood itself - the cross that would have topped it - and its supporting figures of Mary and St John did not, of course survive with it. Note to the right the enclosed pew known as “St Anton’s Cage” which has an amusing history. It was put here in 1534 (and is, therefore, an outstanding survival) by the Nowell family and enlarged by them in 1610 and 1697. We know this from carved initials and inscriptions. Then in 1800 two families disputed ownership of it and a court ruled they were to share it. In the event both families declined to use it and built separate galleries for themselves that were removed in 1909. In fact, Whalley has a number of other interesting enclosed pews. Right: The painted stonework here has you wondering if the chancel is some sort of Victorian pastiche but this composition of triple sedilia, unfeasibly low piscina, aumbry and two lancet windows is in fact original Early English from the early thirteenth century. |

|||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

Left: The chancel. If its congregation and clergy will forgive for saying so, St Mary & All Saints is a messy old place! It’s a personal thing, but I detest self-important monuments to self-important local worthies such as those that disfigure the north side of the chancel here. There’s modern clutter everywhere as well though! It reminds me of our house. Yet this is a vibrant place, loved and used, and it doesn’t exist for the pleasure of visitors such as myself. It’s a family space and, as well know, families have “stuff”. I can’t help wondering, though, what those thirteenth century masons would make of their architecturally austere church now? Right: For a parish church in a small community this is a truly surprising view. A sweeping view of choir stalls and tip-up seats is what you expect in a cathedral or an abbey church. Cartmel in Cumbria, for example, is even more impressive but that was an abbey church that has retained its abbey church fittings after becoming the parish church. Looking here you would never guess that Whalley was not itself an abbey church. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Forgive these cock-eyed photographs but I was dodging low-flying parishioners and in turn trying not to get under their feet! These are the aisle arcades with the south on the left and the north on the right. You cans see that they are very open and almost identical with the exception of the pillars which are, respectively, hexagonal and circular in cross-section. The hexagonal cross section is slightly later, so the masons clearly weren’t able to resist a bit of modernity at the expense of symmetry. This might, by the way, be the first time I’ve seen a funerary tablet (if, indeed that’s what it is) mounted on the clerestory! How unfortunate for those commemorated that it can’t be read without the aid of binoculars. At the west end is the splendid organ sadly shrouded in plastic dust sheets. It dates from 1729 and was acquired from Lancaster Priory in 1813 for what was then the not inconsiderable sum of £300 which is £30,000 in today’s terms. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The shallow north aisle looking east. Originally it was a chantry chapel in 1444 when such Purgatory-avoiding artifices were all the rage. Once known as St Nicholas’s Chapel it is now “The Soldier’s Chapel” and has the British Legion banner hanging from the ceiling. Centre: The south chapel was the Lady Chapel. The Nowell’s (see St Anton’s Cage above) then used it as a family pew. Right: A view of the striking timber roof. It dates from the fifteenth century but asa we can see an earlier, higher roofline on the west tower this is almost certainly a later - but probably not much later - replacement. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The monument to Dr Whitaker, Vicar of Whalley 1809-22, paid for by public subscription and housed to the left of the altar. It’s nice to see a commoner commemorated. Right: A Roman altar preserved within the church. The figure is believed to be Mars and may have been underneath the foundations when the tower was built. Isn’t it remarkable that a Christian church in Lancashire has sufficient confidence in its place in the world to house a pagan altar at a time when ISIS are blowing up priceless ancient pagan remains in Syria? I like that, Bravo, Whalley. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There might be more entertaining misericords in England but if so I have missed them. The church, to its great credit, produces a descriptive leaflet. In fact, this is a church that does everything pretty well from what I can see. These descriptions are paraphrases of theirs with a few comments and additions of my own. Left: Reynard the Fox is a real fifteenth century favourite on misericords and aisle capitals. See Tilton-on-the-Hill in Leicestershire. Here Raynard on the left is escaping with a goose in his jaws. To his left are tiny figures of his family awaiting him. The housewife is asleep, her distaff in her hand. Her cat is also asleep behind her head. Her dog is awake and sitting on his cushion but, it seems, can’t be asked to give chase! The supporters (which, by the way, are a feature unique to English misericords) are carved roses. Right: You get no prizes for recognising St George and the Dragon. The lance is in George’s right hand and you can’t see the business end. This Dragon, unlike many of its ilk, is giving Geworge a run for his money and the horse’s head is in a certain amount of peril. Just visible behind the dragon’s wing a little head is showing. The supporters are dragon heads. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Another stalwart of English mythology is the Wildman of the Forest or “Woodwose”. The character, however, may have its origins in Mesopotamia in the third millennium BC! Here, to quote the Church Guide “he gazes longingly at a noble lady thinking of that which cannot be”. Lust and Chastity personified. Note the club in his hand. In the lady’s left hand she clutches a banner that circles the Woodwose’s body. It says “Penser moit et p(ar)les peu” - Think much and speak little. My parents used to say something ike that to me. It’s interesting that this is in French at this stage in English history. Right: It’s not obvious at first but there are three faces here - the Trinity according to the Church Guide. I’m less sure about this. Traditionally monks were chary about sitting on holy images. Three-faced men are not uncommon in world folklore. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Scolding housewives are a real go-to image in the misericord-carver design book. Mediaeval people were always amused by a “world turned upside down” in which animals played music, bishops were donkeys and, in this case, women scolded their men. This housewife is smacking her unfortunate man around the head with her ladle, grinning wickedly as she does so. He, on the other hand, has taken off his sword and shield apparently and has his hands together in supplication.. This is an interesting image too because a sword suggests someone of noble birth, or at least a soldier. Right: Two birds with pomegranates, Pomegranates which burst with small red fruits were frequently seen as allegories to Christ’s suffering. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: An griffin makes of with a child in its talons. The Church Guide believes this to be a parallel with the traditional legend of a child being carried off by an eagle and found unharmed. The Guide also says that the same legend have rise to the traditional pub name “Eagle and Child”. Right: A dragon (very similar to that which fights St George above) confronts a lion which, on this occasion, represents good confronting evil. Dragons got a terrible press. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: An angel with a bunch of flowers. Right: This one is a real beauty. A blacksmith is attempting to shoe a goose that is being held in some kind of frame. On the left are all his tools in gorgeous detail, although I don’t know what some of them are! On the left you can see his bellows, the nozzle poking into what appears to the furnace with a chimney. Why is the smith doing something so absurd? There is, again, wording beneath - something probably unique to Whalley. It paraphrases the mediaeval proverb that meddling in other people’s affairs is about as useful as trying to shoe a goose. Delicious. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: I’m going to quote the Church Guide here: “Alexander the Great’s “Celestial Journey” is shown on numerous misericord carvings. Alexander wanted to know what was beyond the edge of the Earth. When carried by two griffins he held up two spears of meat so the griffins flew upwards into the sky. Seeing nothing beyond the horizon he turned the spears down in order to descend. On this misericord the griffins are carrying Alexander in a sling. Right: The most ubiquitous misericord theme of them all is the Pelican in her Piety. The pelican was thought to peck her own breast in order to feed her young with her own blood. It’s not obvious why the carver chose to have human heads as supporters whereas many less religiously-themed misericords have flowers or leaves. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: And now the most ubiquitous pagan image of them all: the green man. Right: This is the Abbot’s stall and it is damaged. The Latin inscription says: “May they always rejoice that sit in this seat”. Note the supporters that are carved with the initials of Abbot William Whalley and which are, in an act of chutzpah, topped by crowns! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left Above: Two eagles tearing at the guts of an animal. The guide say’s it’s a lamb but I can’t see any evidence for that myself. The heads of the eagle are actually buried in the unfortunate animal’s stomach. Other eagles form the supporters. Lower Left: Misericords on the north side. There are, as usual, carvings between the stalls but those at Whalley are not as entertaining as in other locations. Right: An old man briding two stalls. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Right: Anglo-Saxon crosses, Whalley churchyard that are believed to date from the tenth and early eleventh centuries. These are not the heavily-historiated crosses such as can be seen at Bewcastle in Cumbria, for example. Nor are they remotely of the same quality. The westernmost cross (right) does have some carvings, however, albeit weathered. You can see a crude haloed figure. Above that, barely discernible, is a bird or it could even be two birds. The Church Guide states quite definitively that below the human figure is the “Dog of Berser” a Scandinavian emblem of eternity representing the Creator. I’m not doubting the accuracy of that but I haven’t been able to find another reference to this symbol other than from a 2013 Journal of Antiquites which uses precisely the same wording so I can’t expand on it. I’d genuinely like to know from whence the attribution originated. Apparently the French word “berser” meant to hunt deer. Its armless cross head looks all wrong and it is generally supposed that it properly belongs on the easternmost cross (below). The cross nearest the porch (south side) is the best preserved (left). I suppose you can interpret the decoration as you will, although Tree of Life is a common idea. The cross head - again armless - has a prominent central boss and it looks like it belongs to the shaft - but that the shaft itself has lost some of its length. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This is clearly a figure with a halo but we don’t know who it was meant to be. Right: The eastern cross. the decoration is badly weathered but just about discernible. The cross head which replaces the original one now mounted on the western cross is alleged to be fourteenth century. Confused? I am! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

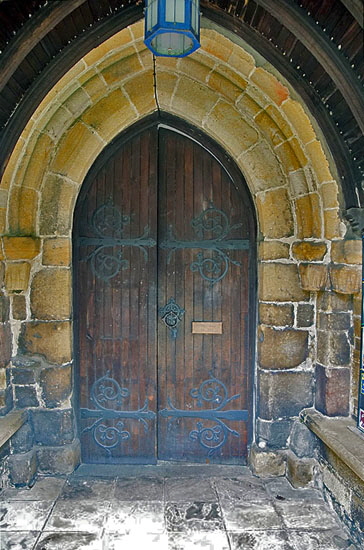

Left and Right: The sides of the southern cross. Right: The south door. The capitals here are the best remaining evidence of the predecessor Norman building that burned down. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Top Left: The head of the western cross that belongs on the eastern cross. Top Centre: The head of the porch cross. Right: The west tower. Lower Left: The north side with the questionable dormer windows and a peculiar little porch. |

|

The Monastic Remains - and a Mystery |

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

I didn’t get a chance to visit the abbey remains properly becasue of a lunch date that had to be kept. The two pictures above are of the abbey’s outer gatehouse. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

Left: Part of the cloisters. Right: Another part of the abbey. Please don’t be guided by this sparse set of pictures. There is actually more left of Whalley Abbey than of most so please do a bit of Googling before you decide whether or not to go. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

site you will be familiar with my strong interest in the work of the late Mary Curtis Webb who proved that such carvings have their roots in Greek philosophy and in particular Plato’s view of the Cosmos. If you ignore for a moment the circle in the middle of this device you will see a square interlaced by four arcs. Mary Webb found exactly that same device in a church in Northampton and several like it in other churches in England. Mary Webb says it represents “The Timaean Construction of the elemental solid: the cube...sometimes used in conjunction with the schema of the four elements”. Yes, this is esoteric stuff and I don’t fully understand it myself but the book (which you can read on this website) is convincing. That this device is another (previously unidentified) example of this decorative phenomenon I am in no doubt whatsoever. What is more, abbeys and monasteries would have been the only repositories of this knowledge. The mystery is less about what it is as about when it was carved. All previous examples were of the Norman era or before. If the face is indeed of the 3rd Earl of Lincoln he died in 1311. That would make this over one hundred years later than any previous datable examples. So was this in fact not from Whalley Abbey at all but from the destroyed Norman church? In which case, of course, we are not seeing the face of the 3rd Earl of Lincoln but one of his forebears. Alternatively, Platonic influences on the informed view of the Cosmos may have lingered longer than previously thought. So if anyone knows any evidence that this is Henry de Lacy who dies in 1311 I would love to know. |

|

Footnote - The Dearth of Religious Scenes on Misericords |

|

There is nothing atypical about Whalley’s misericords, although they are better than most. Misericords might have carvings that are vaguely allegorical or which are religiously “educational” (such as the Pelican in her Piety). You won’t see Christ and his apostles, however. We don’t know why this is but the most popular view is that the monks felt it irreverent to park their backsides on the image of their Lord or the Saints - although it seems an exception was regularly made for good old St George! This is why I rather doubt that the three faced image at Whalley really represents the Trinity. |

|

Footnote - It was Tough being a Monk |

|

Monks didn’t starve. That was the good news. They had to follow vows of obedience, poverty and chastity. That was really bad news, especially the last. By the time Henry VIII and his mate Thomas Cromwell disestablished the monasteries the poverty bit was being largely ignored, at least in the bigger monasteries. The chastity bit was not enjoying quite the level of observance it should either. Most of the hard manual work that early monks endured was now carried out by lay brothers. What the monks couldn’t escape though - and this was the really bad news - was the near-incessant celebration of masses. There were seven each day and monks couldn’t duck out of them. Some of these later monks might have been living off the fat of the land but this was no walk in the park. Many of them would have been arthritic and rheumatic, and early sites were chosen for their remoteness from the attractions of sin and that often meant damp fenland and the like. Nor should we be overly-cynical. The monks’ diet would not have been one long banquet. So you really wouldn’t begrudge them their little tip-up seats, would you? At least when they stood, they could have a little support for their aching limbs. The masses in which they had to participate were: Nocturns; Matins; Terce; Sext; Nones; Vespers; Compline |

|

|