|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

St Peter’s and they are believed to have been royal residences and palaces. A great hall of stone no less than 9 metres wide is dated to before AD875. Edward the Elder, son of King Alfred, drove out the Danes from Northampton in AD921 during his campaign of reconquest. There was a stone church on the site of St Peter’s probably established before AD800 that probably served a royal household. King Edward the Confessor had a great shrine erected here for St Ragener, nephew of St Edmund (of Bury St Edmunds fame). The shrine has gone, of course, but what is believed to be the saint’s coffin lid is preserved - in remarkable condition - within today’s church. After the Norman Conquest, Northampton’s overlordship was largely unchanged. The Saxon lord Count Waltheof, Earl of Huntingdon and Lord of Northampton, had the good fortune to marry Duke William’s great niece, Judith. The nature of marriage at that time decrees that there must have been some dynastic advantage to the Norman family too. Their oldest daughter, Matilda, then married Simon de Senlis (St Lys) in 1089. Simon replaced the simple motte and bailey fortification of the town with a stone castle of prodigious and prestigious size, as well as building another castle at nearby Fotheringhay where, half a millennium later, Mary Queen of Scots would meet her untimely end. He founded Holy Sepulchre Church in Northampton in 1109 after a trip to the Holy Land and another, All Saints, that was burned to the ground in 1675. Two more Simons followed him and the Churches Conservation Trust who now manage St Peter’s postulate the second Simon (b,1090) as the likely builder of today’s St Peter’s, seeing parallels with the church of St Mary de Castro in Leicester. They believe that there was no devotional need for the St Peter’s in a town already provided with at least three churches. Pilgrims were, however, still visiting the shrine of St Ragener. The likelihood is that Simon Senlis II decided to rebuild St Peter’s as a “palatine” chapel for the castle, incorporating St Ragener’s shrine. Its date of construction is likely to have been around AD1130. Everything about this noble church points to this prestigious foundation. One of the most striking things is the straight - and original - roofline from west to east. Inside, as the Church Guide eloquently puts it “The nave marches relentlessly toward the east end with no obvious break for the chancel or sanctuary”. There has been no screen or division: what you might expect perhaps when the church was designed for the high-born. Both inside and out the masonry is of local ironstone highlighted with cream coloured limestone from Blisworth a few miles away. This church looks expensive. If the nave/chancel is striking, a glance to the left (entry is via the north door) reveals the tower arch that is almost breathtaking and, for a non Cathedral church, astonishing. It is very wide and has three orders of decoration. Some of the piers themselves are of sophisticated geometric design and the capitals are adorned with decorative carving. This is the Norman tower arch to match Tickencote’s chancel arch. Again, it screams wealth. The fancy designs of the piers echo those of Durham Cathedral that introduced this conceit to England in 1100. It is surely a deliberate imitation. The whole tower itself was, according to the CCT, in ruins by 1607. It was faithfully rebuilt but moved four metres eastwards, somehow preserving the tower arch intact. The most celebrated feature of the church is the array of decorative capitals, Every one is unmarred by damage and is almost as clear as when it was carved. The designs are not the most flamboyant - those have traditionally been found on chancel arches which St Peter’s lacks - but they are nevertheless masterpieces of Norman work carved by sculptors of obvious distinction. The CCT postulates a connection with the craftsman of Reading Abbey of which a few items of sculpted stone are preserved. Remarkably, the walls of the arcades each have two half-pillars that stretch to the height of the ceiling, each topped by a simply-decorated carved capital. There are two other sculptural features of great interest. Most famous is St Ragener’s coffin lid mounted vertically.. There is little doubt that it is a coffin lid because of the way the decorative motifs are in both north and south orientations: the item was meant to be viewed from above looking downwards. Amongst the motifs is a rare symbol of Plato’s Cosmic Harmony which is documented widely on this website, primarily on my page about the late Mary Curtis Webb who first deciphered this iconography. To complement this the west face of the tower has a large semi-circular band of decoration that clearly adorned the original and now replaced west doorway. This course of decoration not only has many several examples of the Cosmic Harmony design but several others that are probably of Neo-Platonist origin. From the richness of this carving and of the tower arch within the church it is clear that the church originally had its main entrance here in true cathedral and priory church style: again confirming the high status of this church. Both aisles were part of the original church and are of typically narrow Norman proportions. Both walls have been restored and altered to accommodate Gothic-style windows. There are plain original doorways to both north and south of the church, their plainness further emphasising the former primacy of a now-lost west doorway. Above both aisles are original Norman clerestories surmounted by decorative corbel tables. The clerestory walls are faced with arcading and every fifth or sixth arch has a window. It is remarkably decorative in style. Most of the corbels have been re-cut. The blind arcading of the clerestory is mirrored in double courses on all on the north and south walls of the tower, with a single course on the west side. Finally, the east end is of striking Romanesque design. This is, however, the work of George Gilbert Scott who based the rebuilding on the Church of St Cross at Winchester. It is a remarkably sympathetic rebuilding and one can only wish that the Gilbert Scott’s pere et fils had been as assiduous in all of their restorations! It incorporates a peculiar semi-circular buttress that extends as high the nave roof before terminating in a carved capital. Scott had found evidence that such a device was present on the original church. St Peter’s, Northampton is quite remarkable. Any serious student of Romanesque architecture should pay a visit. Simon Jenkins’s two stars is derisory, frankly. This is a place of history and of unassuming architectural grace that has survived for nine hundred years. It’s not for the the seeker after brash aristocratic monuments and garish stained glass. It is a connoisseurs church and surely a national treasure. During my first visit I let in two other visitors. I can only quote one of them who on looking down the church said simply: “b****y hell!”. Amen. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the east. Note the variegated arcade stonework and the consistency of the geometry. Right: George Gilbert Scott’s east end. The Romanesque form is unimpeachable. The painting works surprisingly well and those inclined to deplore it should perhaps reflect that it is the plain walls of the rest of the church that are arguably anachronistic. Ironically the east wall was itself painted over in the sixties but since restored! It is sobering to reflect that every surface would once have been adorned by mediaeval painting. I must say, though, that I’m not enamoured with the cheesy Anglo-Catholic reredos. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

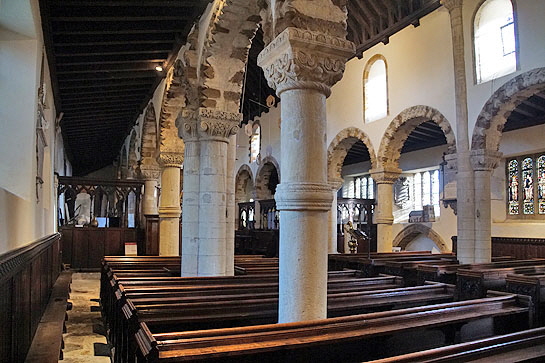

Left: The north arcade. Note the lack of any semblance of division between nave and chancel. Note also the uniformity of the chevron-decorated pillars. The variegated masonry and the the regularity of the geometry allied to decorated capitals make for a really classy and restrained composition. Right: Looking towards the south arcade from the shallow north aisle. Note in the foreground the collared pier - a very unusual luxury for a non-cathedral church and also between the two pillars on the right the half pillar reaching from floor to ceiling to help support the roof. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Tower Arch. It has four courses of decoration (counting the thin outer course) and four sets of columns - the outermost are not visible in this picture.. Three of the columns are decorated. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The south side of the tower arch. The two inner columns are decorated with basket work and chevron. The capital decoration is fairly restrained with rather more imagination given to the abaci (the place where the capital meets the spring of the arch). Right: The north side of the tower arch. One column has barley-sugar twist decoration. Note that the outermost columns on both sides have collars that match some of those on the arcade columns. This doorway is very much as a piece with the rest of the church’s sculptural scheme. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

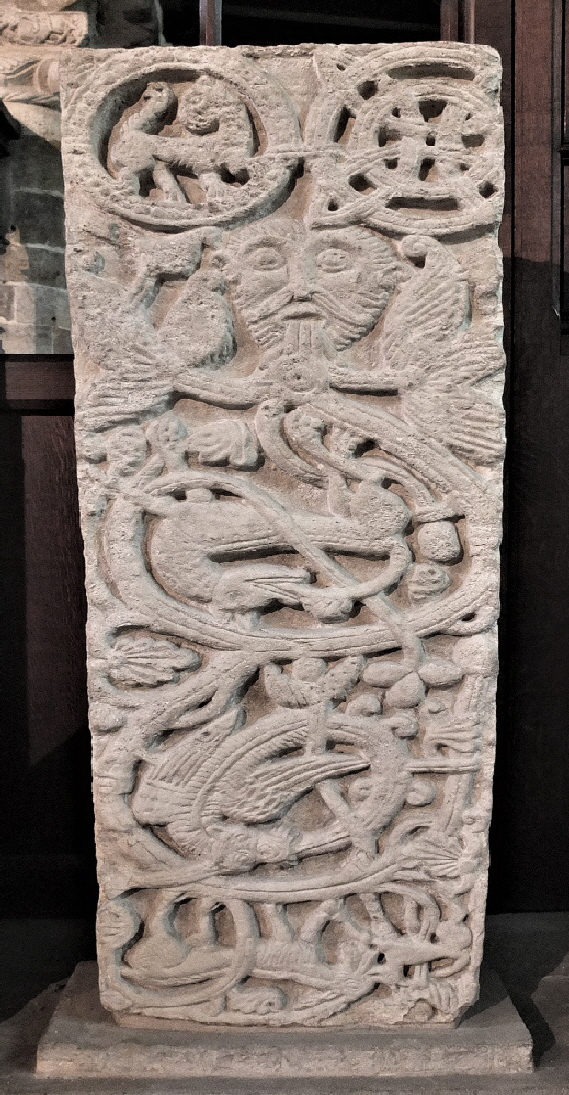

Above: The supposed grave slab of St Ragener. It is an extraordinary thing and clearly marks someone of substance. At the top of the right hand corner is the circle interlaced with arcs motif identified by Mary Webb as representing Plato’s “Cosmic Harmony” and which is also seen in profusion on the west side of the tower. This motif is not an everyday one and the theme is obviously abstruse. I know of only one other in England on a grave slab and that is at St Bees far away on the north west coast of Cumbria. This was clearly something understood only by the educated monks and where we see this symbol then we must presume a monastic behind it. (Photo: Bonnie Herrick). Right Top: Rotated 180 degrees this is a close up of the cross slab showing a beast devouring what looks like his own tail but might be the tendrils of a vine. Right Middle: Again rotated through 180 degrees. This could be a goat or a deer having his head bitten by a dog - although it looks quite a friendly scene! Right Bottom: This is not from the grave slab but is a carving from an abacus of the south side of the tower arch. It is (perhaps) a lion either devouring or fighting his way through a mass of tendrils. This is the only animal motif on these capitals, although there are many more on the arcade capitals. |

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

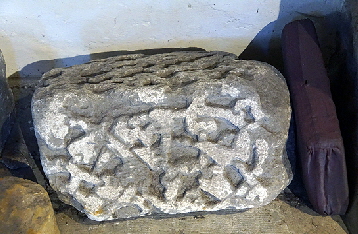

Top Left: An animal (cat?) with a human head within a roundel. Top Centre: The Circle with Arcs symbol of Cosmic Harmony. Bottom Left and Right: Ancient pre-Conquest stones preserved within a tomb niche in the south aisle. The interlace work on the right hand stone is particularly fine and may have been part of a cross-shaft. Right: Looking towards the west end. Such is the magnificence of the tower arch that it takes second look to verify that we are not looking towards an east end. |

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Left: The decision to relocate the west doorway decorative courses to the first floor level during the 1607 rebuilding of them tower was a curious one. Aesthetically, surrounding a rectangular window it just looks “wrong”. Its size is a reminder of how grand the entrance must have been. Not only grand, but unique. As a purely decorative feature it would have been extremely unusual. Where are the normal decorative courses of chevron moulding, beakheads and the like: this church was built during the heyday of both of these features? The answer, of course, as Mary Webb has conclusively proven is that the apparently decorative designs were in fact symbolic. It is intriguing, however, that the decoration was preserved, since this meaning would surely have been utterly lost to the masons and designers of 1607. Even were this not so it is totally implausible that they would feel it to be symbolism still worth preserving. They surely, then, did preserve it simply as decoration or perhaps to preserve as much as possible of the original tower. We must be as grateful as we are mystified by their motives because, as we shall see, it was clearly not a straightforward task to dismantle and reset it. Right: Here we see no fewer than three circle with arcs symbols. This outermost course of the three is the one that displays variety whereas the second course is all composed of a rhombus and saltire cross motif whilst the inner course is purely decorative. |

|

||||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

Left and Centre: The extremities of the decorative courses give us a chance to think about the designs in more detail. If the outer band is symbolic and the innermost decorative, into which category do we place the second course? Mary Webb sketched this and several other designs in her book under the heading “Interlaced squares and other geometric figures”. Her book outlines the way in which Greek philosophers - especially Plato - saw mathematics and geometry as being inextricable parts of and as symbols of the Cosmos. They were part of and representative of the created universe. The philosophers, of course, pre-dated Christianity. To them it did not matter who or what was the “Creator”: all they were exploring was the nature and “harmony” of what was created. This is why, of course, their thinking was not incompatible with Christianity. Cosmic harmony could be seen as a celebration of what God had created, just as today’s Christians might see the same thing in the mathematically perfect spirals of a mollusc shell. The rhombus (or square) and saltire design here might well have been, unlikely as it might seem to our eyes, as representation of the cube - the so-called “elemental solid”. Within the context of the symbolism of the outermost course we must say that the balance of probability is in its favour. In the left hand picture, note the second design from the right. This is a square interlaced by arcs and it also encloses a circle. This design was also sketched by Mary Webb although, oddly, she overlooked the inner circle. The same design - without the circle - can be seen on the neo-Platonist font at Sculthorpe in Norfolk and on a capital preserved in Rouen. Another geometric design can be seen in the right hand picture towards the top. The use of this obscure symbolism is thought-provoking. Firstly, it reinforces the high status of the church. This was symbolism for the educated elite, not for the unwashed hoi polloi and doubtless Simon Senlis reveled in his own intellectual knowledge. Secondly, the CCT postulates Reading Abbey (now ruined) as the source of all of the sculpture here, despite their own ignorance (no insult intended) of the significance of these motifs. Reading Abbey is precisely the place that Mary Webb identified as the likely intellectual wellspring for the definitive Neo-Platonist designs on the font at Stone (originally at Hampstead Norreys) in Buckinghamshire. There is a strong counter-argument, however: in the late eleventh century Simon Senlis founded a Cluniac monastery in Northampton itself. That begs the question whether this would not have been the intellectual centre for Simon’s church? Moreover, Reading Abbey - another Cluniac foundation - was not founded until 1121. Could Northampton Abbey have influenced both St Peters and Reading Abbey? On the face of it this seems more likely. although most assume the reverse to be true. Note that some of the sculpture looks too “flat” compared with the heavy undercutting of other motifs. It looks as if some repair and re-carving was done during the tower rebuilding. Right: The west tower which was rebuilt after its near-collapse in 1607. The reconstruction of the single course of blind arcading was somewhat bodged in the view of the CCT. The corbels are re-cut. Note the unusual and rather elegant round-profile buttresses at the corners. |

||||||||

|

The Arcade Capitals |

||||||||

|

The capitals are almost intact and are a true treasure. How many sculptors were involved is difficult to deduce - my own guess is two - but the style is more or less consistent throughout. I have seen it described as “rather formal style reminiscent of metalworking” and that struck a chord with me. On the one hand is a wide range of freelance but persistent foliate designs .On the other is a number of beasts, each of which is almost without exception devouring surrounding plant tendrils. There is one instance each of a man (or woman) and another of geese. As the capitals have a square profile, there are of course four canvases for carving on each capital. It is noticeable that the four sides of any given capital are generally consistent in theme and style. t The abaci are, again, mainly stylised decorative designs but there are some nice representation of writhing beasts and dragons, as well as a couple of which have the sort of Romanesque decorative designs that we are more used to seeing around doorways such as chevron. In or two places it is possible to speculate that some degree of repair or recutting has been carried out. There are many capitals and each has four faces. I have chosen not to show each face but the photographs show at least one face for each capital. Nor have I chosen to describe each, thereby assuming that I have no more insight than you have! |

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bottom Two Pictures by kind permission of Bonnie Herrick. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: One of the floor to ceiling columns in the north arcade, topped by a Romanesque capital. Centre: The blind arcades on the south side of the tower. Clearly much of this was rather inexpertly repaired or re-cut - especially the corbels and upper arcade - but this barely detracts from what is still a very authentic Romanesque facade. Right: The north doorway. |

|

|

|

Left: The north side of the tower. Note the twin decorative string course below the blind arcades. Right: The church from the south side. The aisles have been somewhat disfigured by inappropriate - one might say ghastly - rectangular windows and - definitely ghastly - a chimney. To the right you can see a a Romanesque window in the chancel. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Amongst the many unusual and high status features of the church are columns with beakhead-like feet at the point where the chancel area and the nave areas meet. Right: The view from the north side which unusually has been spared the boiler house chimney that has been allocated to the normally more favoured south side! Again, you would have to say that that the incongruous aisle windows are unfortunate blemishes. Grim. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The south chancel clerestory. This seems to have been heavily restored but, again, this in no way spoils what is still an essentially Norman church. The variegated voussoirs are very pretty. This particular group pf corbels also looks to be new, although there are still some original ones scattered around the church. Right: The same aspect of the north side. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Gilbert-Scott’s east end. The half-pilllar buttress is thought to have been an original feature. Only the two quatrefoil windows, perhaps, look a little inauthentic. Given what remains of the church that most certainly is original we can be pretty sure that Gilbert-Scott has created something very like the original. Right Top: Quite where Gilbert-Scott got this capital to cap his east buttress, I don’t know. For all I know it might be the original. I very much doubt it, though. because it has ionic scrolling that is totally out of keeping with anything else in the church. A mystery! Right Centre and Bottom: We don’t know for sure which corbels are Victorian but these look absolutely authentic original Norman to me. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Finally, these corbels look very original. Note in particular the double corbel on the left. A man is playing a viol. He may also be mounted. I can’t make out the one to his right as it has been badly weathered. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote 1 - Access |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Located where it is, in the town centre, the CCT cannot leave this church unlocked. It is, however, surprisingly easy to visit. For a start off, there is a public car park only a couple of hundred metres away. Current Access information (7/5/2025) is as follows: “The church is available to visit by appointment. Please contact The Friends of St Peters at Stpetermarefair@gmail.com or telephone 07522 792392. A word of warning: there are quite a few keys. You have to unlock one of the two gates through the railings that surround the church. Entrance is then through the SOUTH door even though the north door looks more obvious as it is the first one you see and is inside a porch. We spent quite a few minutes trying to get the south door open before realising we were at the wrong door! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote 2 - ‘Amptons and Musings about “Saints” |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ever wondered why England has a Southampton and a Northampton? It seems that both towns were once known as Hamm Tun - the village by the bend in the river. North and South were appended to their names to distinguish them. If you add “scir” to those names it means their surrounding area. Thus we get “Northamptonshire” as the county name. In the past what we now call “Hampshire” was also known as “Southamptonshire”. Oddly, the leading sports teams for both of these towns - rugby union in Northampton, football in Southampton - are known as “The Saints”. This is coincidence. Northampton Saints (a terrific and “real” club, by the way) were founded in 1880, by Reverend Samuel Wathan Wigg. He was the curate of St. James church. Thus they were nicknamed the Saints and also occasionally “The Jimmies”. Southampton FC were formed as St. Mary's Church of England Young Men's Association in 1885 and were therefore also known as the Saints. Many of the most famous English sports clubs were founded by local churches or clergymen in the nineteenth century. It was their way of encouraging young men to adopt a healthy pastime rather than the less palatable alternatives! My own beloved Aston Villa were themselves founded in 1874 by members of the Villa Cross Wesleyan Chapel in Handsworth, Birmingham. So now you know how they got their distinctive name as well. It is said that Prince William became a supporter because when he was at Eton the “bloods” all had to support a team and he liked the peculiar name and wanted to support a team that was unfashionable. Unfashionable in Eton, that is.. “Saracens” rugby club has similar associations, having been formed by Knights Templar returning from the First Crusade. This website takes you into places no other church website would go, doesn’t it? Oh, and I made that last bit up. Did I fool you for a second or two? According to their website “Sarries” were “founded in 1876 by the Old Boys of the Philological School in Marylebone, London (later to become St Marylebone Grammar School). The club's name is said to come from the "endurance, enthusiasm and perceived invincibility of Saladin's desert warriors of the 12th century"”. So they could have become the Saints too! The team of the last few years certainly live up to their original billing. Mind you, I remember them when they were absolute rubbish. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||