|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

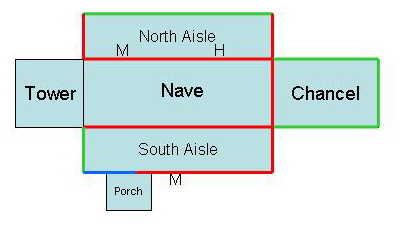

Tilton-on-the-Hill is for me the embodiment of the joys of the English parish church. With it’s gorgeous ironstone exterior it positively glows in the sunlight. It has evolved, of course, over the centuries but you feel that not one change has been made that was unnecessary or done in doubtful taste. Even the Victorians seem to have contained their “modernising” zeal. It is every inch the village church. Domesday recorded a priest here in AD 1086 so we can be sure there was a pre-Conquest church here but of that nothing remains except, curiously, the font. The church was rebuilt in around 1180. It was a three-celled affair with nave, chancel and the lowest stage of the present west tower. In 1180 you might have foreseen a late Norman or Transitional style but in fact what little remains of this church is in the Early English style and this is especially conspicuous on the tower arch and in the lancet west window. There’s not a round arch to be seen. Unusually, the floor plan of the chancel does not seem to have changed from that day to this, despite the many phases of redevelopment since that time. A south aisle was added in about 1260 and the windows we see today are original. It is gabled which is quite unusual for the area. They are in early Decorated style so, once again, Tilton was bang in line with architectural fashion. The Church Guide (the one I have, remarkably, is dated 1996!) speculates that the south aisle was commissioned by Sir Jehan de Diggebye whose effigy - and that of his wife - are located between aisle and nave and have been dated to 1269. If Sir Jehan (John?) was the founder then it is a fairly safe bet that he also endowed a chantry chapel for himself and his family at the east end of the aisle. At some time, the tower also was raised by two more stages in early Decorated style as evidenced by the early Decorated style windows to west, south and north. That of the east side is, however, in Perpendicular style. The north aisle followed later in the thirteenth century. It is surprisingly shallow, more in keeping with Norman practice, and has a lean-to profile making the two aisles asymmetric. The arcade has some carved capitals of beasts and this reflects the revival of church sculpture during the Decorated period, having become almost moribund in the Early English. For reasons we can’t understand, the arcade was aligned at right angles to the north side of the tower arch. This gives the church a curiously asymmetric look from the inside too. Just to really confuse things the masons seem to have taken down the chancel arch and relocated it a couple of feet to the south as if to avoid a similar aesthetic issue. I don’t know whether this was done at the time or later. Either way, it seems that the ground plan was seen as sub-optimal but presumably alterations to the tower or the aisle to “improve” the west end were just too complex. The north aisle windows we see today were replaced in the latter part of the fourteenth or early part of the fifteenth century. As we will see, almost every roofline of this church has a sub-parapet cornice friezes with masses of carvings. None of these, however, were contemporary with the structures they adorn. They surely were added during an early fifteenth century rebuilding phase when the nave walls were raised in order to create a clerestory. I believe that the aisles acquired their embattled parapets at that time, and that their rooflines were altered, probably to lower the pitch of the roofs to facilitate the installation of lead which would “creep” down from a steeply-pitched roof. The clerestory itself is similarly adorned and it is almost inconceivable that the decoration was not all added at the same time. Similarly, gargoyles were now needed to take water away from the freshly-parapeted roofs. This is a pattern that has emerged amongst all of the churches I include in my book, “Demon Carvers and Mooning Men”. The Church Guide supports my view that this was a single program of work but dates it as late as 1490. This is much too late for carving in this style and, as we will see, the very same masons carved at other East Midlands churches. What we can say is that the clerestory is an unusually lofty and fine one and it is very much in the Perpendicular style, although the windows are eighteenth century. After that the church, like most others, was tweaked here and there with new windows but the structure was substantially unchanged thereafter. There was refurbishment in 1850 but this left the structure pretty well as it has been since the fifteenth century. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

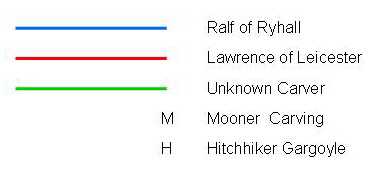

us his best collection. The Gargoyle Master and Ralf of Ryhall both left us some eyes made from molten black lead, although as usual some have disappeared over the years. Besides Ralf and Lawrence there was another frieze-carver here who decorated the chancel and some parts of the aisle. The carvings are small and distinctive with large drilled eyes. It could be that this was one of the MMG masons carving in a different style but some of the the fleurons are distinctive and repetitive and if it was one of the MMG masons I would have expected to have seen these elsewhere. As matters stand, I believe this mason also carved at Beeby in Leicestershire just over six miles distant. We should not be surprised. I have explained elsewhere that most masons would have had permanent homes and that, with the exception of the enterprising (and possibly unmarried!) John Oakham, they were reluctant to work too far away from those homes. The likelihood is that this unknown mason simply joined the MMG when it was working nearby, replacing someone who was not willing to work on this western fringe of the MMG area. The masons were not here just to carve friezes and gargoyles, so what were they here to do? They certainly raised the clerestory and to facilitate this it seems they re-profiled the arcade arches because we see spandrel carvings from that time, including one with the tell-tale goffered caul headdress. The Church Guide says that the chancel was re-roofed at this time (although, as previously noted it dates it several decades too late, possibly deceived by the replacement clerestory windows) and that is supported by the rather odd sub-parapet frieze that matches some of those on both aisles. There is no indication, however, that the aisles were expanded as was the case at several other MMG churches. What seems to have happened is that re-roofing was not confined to the chancel and that the aisle roofs were leaded and the ugly material hidden behind parapets which were in turn adorned by the sculpted cornice friezes. To take the water away from behind the parapets the Gargoyle Master carved his splendid gargoyles. The plumber, as usual, indulged the Gargoyle Master and Ralf of Ryhall to, as was their wont, make black eyes for their carvings out of molten lead. The parapets are something of a muddle. with an odd mixture of plain and embattled. I have remarked elsewhere that parapets were not cheap (see The Cost of it All) and embattlement was surely more expensive. I think the parish had probably over-reached itself financially and was trying to find economies. This might also explain the pretty dire quality of some of the parapets that seem to have been cobbled together with off-cuts of limestone! This is not a limestone area - hence the ironstone walls - and transport costs for limestone for the parapets and cornices must have been steep. It took a distance of only about ten miles before carting cost of stone exceeded the quarry cost. Finally, we need to refer to Lowesby Church, only a mile away. It too is an ironstone church and interestingly the parapets there also seem to suffer from low-quality stone. More interestingly, Ralf, Lawrence and the Gargoyle Master were there too and there is a mooner and a hitchhiker gargoyle. It seems almost certain that the two churches were worked on consecutively or even concurrently. We can easily imagine the consternation in one of those parishes at the developments just down the road. It is my suggestion that where the MMG was moving from site to site the “finishers” - the parapet makers and cornice carvers were left behind before joining the rest of the team at the next site. A model whereby the hewers and layers sat around (unpaid) while the finishing touches were applied makes no sense whatsoever. The contractor-mason(s) of the MMG, I suspect, would take few lessons from modern builders as to how to best deploy his workforce, |

|

The Church |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Of the Mooning Men Group of churches Tilton-on-the-Hill is one of the few that is of great interest other than for its carvings.. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The church looking east. Note that the the centre of the east window (and therefore the roof) and the centre of the chancel arch are not aligned. Youcan see quite clearly that this has occurred because the chancel arch has been moved slightly south and that it originally made a junction with the easternmost arch of the north arcade. Right: The chancel and its arch his late twelfth century although there is little to indicate this as it was not built in Norman style. The east window is a rather peculiar affair in a very plain Perpendicular style. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: If the east end is not quite aligned correctly then the west end is downright bizarre! The north arcade and the tower arch make a clumsy junction with each other. It is very odd indeed and (see above) was originally mirrored at the east end. The original twelfth century church must have been built with external walls that were symmetrically placed in relation to the west tower. Why then was the north arcade moved further to the south in this fashion? It can’t, with all due respect, be for better aesthetics! There is speculation that the tower needed buttressing. I’m no engineer so I can’t comment on that theory. Note the similar designs of the two aisles. The later north arches, however, have slightly more sophisticated profiles. Right: The south aisle looking east. To the left you can see the tombs that form part of the separation between aisle and chancel. Both aisles have gabled roofs which, in my view, always adds a touch of class to a church. The south windows are original but the east window - a very generous one - is in later Perpendicular style. It has also been badly distorted by subsidence. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The south aisle looking towards the west. Right: Triple sedilia in the chancel. The cusped ogee arches tell you this is much later than the structure itself, |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Double piscina and aumbry, south aisle. Right: The tomb of Sir Everard Digby 1446-1509. This Sir Everard is not to be confused with a later Sir Everard (1578-1606) who was a prime instigator of the Gunpowder Plot in 1605 and for which he suffered the customary horrible death. There is an (almost certainly apocryphal) tradition that the plot was hatched at another Digby church at Stoke Dry in Rutland. The Sir Everard whose monument is shown in this picture had many offspring. One of his sons was Simon Digby, known as Simon Coleshill Digby. Simon became Deputy Constable of the dreaded Tower of London and he brought to trial Sir Simon de Montfort (a descendant of the man who supposedly “founded” the English parliament and slso of the man who was such a butcher in the dreadful Crusade against the Cathars) who had supported Perkin Warbeck in his doomed attempt to usurp King Henry VII. de Montfort was hanged drawn and quartered in 1495 and the manor of Coleshill which belonged to the de Montfort family was given to Simon Digby. He was the first of the family to be buried at Coleshill Church in Warwickshire - the town whose Grammar School I was privileged to attend. There were “houses” bearing both the Digby and Montfort names! The single fleur-de-lys emblem which is prominent on Sir Everard’s shield and around the tomb is the Digby family crest, of course and is still on the school crest even though it changed from Grammar to Comprehensive status decades ago. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: We haven’t finished yet with the Digbys. This is the effgy of Sir Jehan (John) de Diggeby (1234-69) and behind him his wife, Arabella. Right: The font with its scallop pattern is clearly Norman. It looks, in fact, very like a Norman capital but as there was never a Norman aisle here that seems unlikely. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

One of the north aisle arches is adorned by this splendid set of carved animals. Top Left we have a fox - possibly Reynard - clutching a goose in his mouth. The mason obviously had little idea how to carve a fox, but the tail is at least of brush-like proportions! Top Right: Lest we think Reynard is just any old animal with a goose in his jaws we here now identify a crowned lion. In the Reynard story the Lion ruled the Kingdom and ultimately condemned the mischievous and evasive Reynard to death. I confess the other two figures are beyond me! The Reynard story has a number of other characters. I’m guessing that the figure lower right is the bear (“Bruin”) with perhaps a chain around his neck? That leaves a couple of candidates for the character Lower Left: Possibilities include the cat (“Tibart”) who defends Reynard and is then tricked for his pains and the Panther who was Reynard’s accuser. Pevsner suggests there is a monkey. I can’t see that in any of these figures myself. The Church Guide talks of a lamb. Well I know this mason was no expert on animal anatomy but surely none of these figures is a lamb? Nor am I aware (although there are many versions) that a lamb appears in the fable. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Another capital is adorned with angels - and electric heaters! Right: The lowest stage of the tower is from the original church and is in the Early English style. The limestone blocks contrast wonderfully with the ironstone used in the main structure. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Tilton Church has a remarkable set of carvings both inside and out. There are corbels supporting many of the roof timbers, exhibiting some interesting insights into the headwear of the day. They obviously had to be contemporary with the clerestory of which they are part so these were executed by the Mooning men Group. Centre Lower: This poor chap single handedly has to support the easternmost arch of the north arcade and he doesn’t look too comfortable with the job. Tilton also carvings on the spandrels of the arcades. The most important (top right) sports the MMG’s ubiquitous goffered caul headdress that allows us to deduce that the MMG remodelled the arcade arches (but not the columns) to facilitate the insertion of the clerestory. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The church from the south west. The west window of the south aisle is a nice example of an early geometric Decorated style window. The doorway to the tower was added long after the Norman base section was built. Centre: The west tower. Right: The effigy of Sir Kenelm Digby. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Just to give a flavour of the carvings here, the picture above shows sections of the south aisle and clerestory. There are distinctive and cheerful gargoyles as well as frieze carvings. Just visible on the left on the aisle you can see part of one of the two mooners on this church. The key to all this carving is in the parapets. Unusually, these are rather crudely manufactured seemingly from odds and ends of stone. The carvings do not date from the building of the various structures of the church but from the reconstruction and remodelling of the roofs. They were almost certainly all carved during a large scale piece of work that involved the the building of the clerestory, the addition of the decorative parapets and the leading of the roofs. This pattern emerges in nearly all of the churches in my Mooning Men Group narrative.. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Let’s start with a few of the gargoyles. This is a classic set by the man I call the Gargoyle Master. His most iconic design is what I call the “hitchhiker” gargoyle (top left). A woman sits astride the smiling monster, whilst he clutches another underneath. The hitchhiker design can also be seen at Lowesby, Wymondham, Owston (all Leicestershire) and at Oakham and Empingham (both Rutland). You can see another example of another gargoyle with a head between his legs bottom right. These are characteristic of this carver. In the bottom row centre is a monster seemingly holding apart a set of toothy jaws. This too is a design that recurs at Knossington and Wymondham in Leicestershire and at Buckminster in Lincolnshire. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Centre: The two mooning men. on respectively the north clerestory and the south aisle. Right: This rather cheerful face is typical of the mason I call - because he operated mostly within this county - “Lawrence of Leicester”. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

These three carvings all appear on the south aisle. I believe these to all be by Ralf of Ryhall. Note particularly the black eyes in the right hand picture. These are made off lead. How many cavings would originally have had them is impossible to estimate. I have seen several where one eye is missing or where only a “root” remains. Many will have been lost altogether. The home of this device is Ryhall and there are many more at Lowesby. The Gargoyle Master used it too. I believe it was used only by these two masons. Apart from their rarity - I have seen no examples on external carvings outside of the MMG area - they also support the notion that the carvings were done during re-roofing projects. Working in lead was a desperately dangerous activity carried out by “plumbers” (that is, workers in lead) and not by masons. Plumbers were likely to be on hand for the manufacture of lead roofs and rainwater goods. This would also explain why one of the most enthusiastic users was the Gargoyle Master. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Centre: One of the trademark carvings of Lawrence of Leicester is these “lions” which he liked to put at the ends of friezes he carved. Note the odd little trident-like tails, Right: A face-puller by Lawrence of Leicester. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

We have looked at the carvings by three of my “named” masons. There is, however, a very large group of carvings that cannot be easily attributed to any of the three. The style might be best described as “naive”, to which one might add “good natured”. Fleurons are the main theme with a smattering of cheerful grotesque faces. They surround the chancel but also, significantly, some considerable lengths of the aisles. This tells us that they were all put in place during the same phase of the church’s development as outlined above. Note in the upper picture of the west end of the south aisle there is a head surrounded by a square-shaped headdress which is characteristic of the Mooning Men Group of masons and which can be dated to the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries. You can see even better examples on some of the gargoyles pictured above. As previously noted, this suggests that the claim that the frieze-bedecked clerestory is as late as AD 1490 is decades out. It is impossible to rule out completely that this set of carvings was not carried out by one of the other three masons. The cheerful faces are characteristic of Lawrence of Leicester and the styles of this group of masons were nothing if not inconsistent. It has to remain an open and unanswerable question. This style is seen at Beeby Church about six miles away and was obviously carved by the same man. Note the poorly executed parapet at the point of the gable. Also a cornice that does not seem to have been altogether well-planned with lengths of different size. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Frieze carvings, Beeby Church, Leicestershire. You might take the view that the carver lacked skill. Looking at the bizarre Green Man figure in the upper picture I think we are seeing an ironical sense of fun from someone just playing it for laughs. Look at some of his fleurons on the Tilton friezes. This man could carve. Think now of modern cartoonists and satirists: Gerald Scarfe (my hero) for example or the late Carl Giles. Their techniques were defined by what they are trying to communicate. Everything we see of the mediaeval masons tells us that they just didn’t take external frieze or gargoyle carving seriously - hence the mooning men! Like all of these decorative carvers, this man did it his way. That, of course, means that we can’t rule out the possibility that Lawrence of Leicester or Ralf of Ryhall just decided to carve in a different style for a change. Just because he could. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||