|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

“Dark Ages” tradition until the cross was erected as early as the seventh century or possibly in the eighth. The fact that it is here at all possibly gives testament to the continuing tradition of re-using sacred sites. The Romans had re-used the site of Cocidius’s shrine. By the time the Romans left Britain the Emperor Constantine had made Christianity the official religion of the Empire. Doubtless in this remote outpost the soldiers clung to the old ways more tenaciously than in Rome itself but it is still inconceivable that the garrison here did not have a Christian church of some description. In this part of England after the departure of the legions the main Christian influence would have been from the Celtic missions from the east. No post-Roman coins have been found in the vicinity so it doesn’t seem likely that there was a settlement here that would have justified a church as we know it. Yet the cross is tall and elaborately-carved, far too grand, one would have thought, to mark the outdoor meeting place for a scattered Christian congregation - a so-called “preaching cross”. So its purpose is a matter for speculation. What is not in doubt is its approximate age. It has runic inscriptions that commemorate King Alcfrith, son of King Oswiu, who himself convened the Synod of Whitby in AD664 at which Roman Christianity triumphed over the Celtic tradition. About AD680 is the best estimate. As we shall see, this is a cross with much imagery. Pevsner made the point that much of it is of Egyptian Coptic provenance, reinforcing the links to the Irish-Celtic monastic tradition which was itself influenced by that branch of Christianity. He also makes the point that the Gallic masons employed by Benedict Biscop and used in building the great monasteries of Jarrow and Monkwearmouth had no tradition in naturalistic carving. The Synod did not proscribe Celtic Christian traditions and the decades following saw a process of assimilation and consolidation, not of eradication. This, then, seems most likely to be a cross of Celtic craft traditions that claims the area for Christianity. But feel free to develop your own theories! I have said it is a cross, but of course the actual cross head is missing. A fragment was found in the seventeenth century but after passing through the hands of a series of antiquarians of the day it was lost. The site acquired renewed military significance in 1092 when William II annexed Cumbria from Scotland and a castle was again built here. Presumably it was of the motte and bailey pattern. In 1340-60 the present castle was built using stones from the Roman fort. It is testament to the sparse population of the area that after nine hundred years the stone hadn’t been long since carted away. After cycles of decay and repair it was finally demolished in about 1640 just before the Civil War. So what of the church itself? It is a simple single-celled rectangular building with no separation between nave and chancel and with a western tower. The Church Guide puts its building date at 1277. The east window is an Early English style triple lancet and this is the only wall that survives from that time. Pevsner puts it at about 1200 but 1277 is just a plausible. One imagines that Bewcastle was not amongst the first areas to adopt the new-fangled Decorated style! On the other hand, I find it hard to imagine there was no church of any kind on the site between 1092 and 1277 (or 1200 for that matter). Is there a Norman church below? The church was known to be in a parlous state by 1703. It was rebuilt in 1792 with seventeen feet being shaved off the west end and the western tower was added. It was altered again in 1792 and rebuilt in 1901. So we have a very vanilla and un-historic church sitting on a site of great historical importance and adjoining one of the greatest surviving Anglo-Saxon antiquities! |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

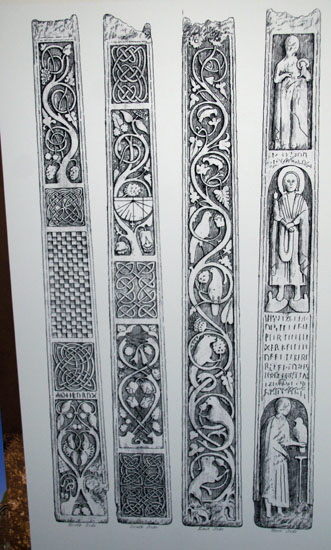

Left: The cross from the south west. The west face has three panels with biblical figures, interrupted by another with the runic inscription. The northern face has three panels of Celtic style interlaced decoration interspersed with two of vine scrolls. The second panel from the top incorporates a sundial. Centre: West face bottom panel. The figure is nest to a large bird sitting on a T-shaped perch. In the man’s hand is a stick. The Church Guide prefers the explanation that this is St John the Evangelist with his trademark eagle. But John was usually represented as an eagle not with an eagle. What makes me more sceptical still is the lack of a halo. Surely the sculptor would not have omitted something so important? Christ’s halo on the panel above is very conspicuous. An alternative theory is that this is the Alcfrith whose death is commemorated here. Kings loved their falcons. I lean heavily towards this interpretation. Right: West face central panel. Christ (or certainly a holy figure) holding a scroll and standing on two animals β“ an adder and a lion according to Pevsner. Note the conspicuous halo! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

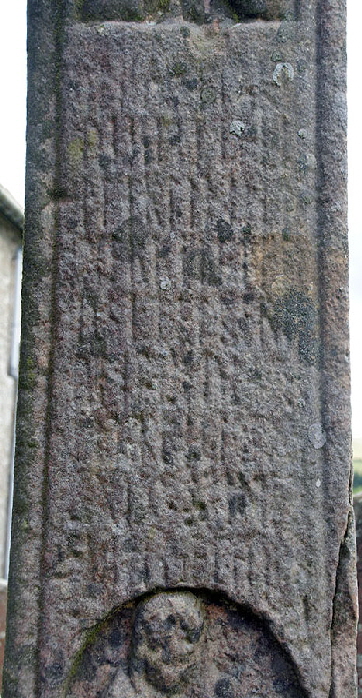

Left: West face topmost panel. Thought to be St John the Baptist holding an agnus dei - Lamb of God. I have to admit I can’t see any halo here either. However, this is a much more badly weathered image so I guess that explains it. Centre: West face bottom panel but one. This is the runic inscription to Alcfrith - “ conveniently next to Alcfrith’s possible image if you prefer it to the St John the Evangelist theory. The runes are being weathered (and we really should be doing more to protect them, surely?) and not easy to discern. The general interpretation is: “This Victory Cross set up Hwaetred, Olwfwolthu in memory of Alcfrith a king and son of Oswiu. Pray for his soul”. Right: South face top two panels. There may have been a runic inscription above this section. The upper panel is simple interlaced decoration. The one below has vine scroll decoration and a sundial of which little is known. There is speculation it may have been recut but this might be the oldest sundial in England. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: South face, third and fourth panels from the top. A more elaborate and very Celtic decorative panel above some more vine scrolling. Centre: South face, lowest panel. Some very fine interlaced work Right: The East face has what the Church Guide calls an “inhabited vine scroll”. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Three Views of the east face with beasts and birds filling the vine scroll work. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: North face. Under a bright noonday sun, crosses can be well-nigh impossible to photograph satisfactorily and this was the best I could do. This face has another mixture of vine scrolling and interlaced decoration. Curiously, however, the central panel is a chequerboard design that is out of kilter with the imaginative and free-flowing designs elsewhere on the cross. Second Left: The topmost panel with vine scrolling. Second Right: North face, middle section. The chequerboard pattern predominates. Note the similarity between the interlaced design here and that on the top panel on the south face. Far Right: The lower part of the north face. Note the similarity here between the interlacing with that at the base of the south face. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The interior of the church looking east. There is no separate chancel area. This is very much a post-reformation church. Right: The interior looking west. It has a west gallery presumably from the 1794 rebuilding when such things were very fashionable. The church may not be ancient but it is a pleasant one and hard not to like. Mind you, I was there on a glorious sunny day. The whole site must be pretty bleak on a wet, windy day - and those days are from unusual in these parts! Hpw, one wonders, must legionaries from the Mediterranean have fared here? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The view from the south west with the cross in the middle foreground. The faux Early English south windows presumably date from the 1901 rebuilding. Right: The north wall is conspicuous in the absence of any window or door openings. If you lived on the Scottish Borders you would probably avoid north facing windows too if you could! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: All that remains of the castle. They didn’t make a great job of demolishing it. Right: The church has a little Visitor Centre adjacent and this helps considerably in understanding the cross and its context. There can’t be many more remote Visitor Centres in England. It is not elaborate but it certainly adds to your visit |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

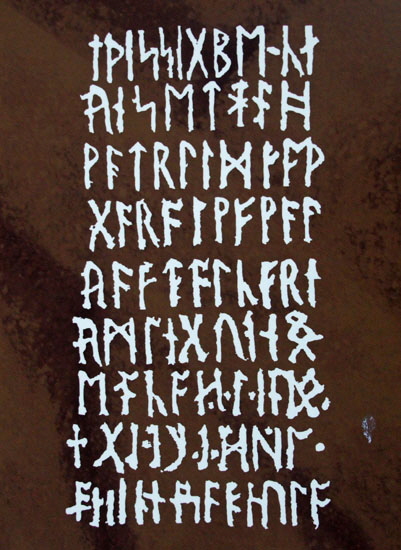

I shamelessly reproduce here some of the material from the Visitor Centre as it will enhance your understanding of the photographs. Left: This representation of the cross reminds us that it would originally have been painted. The representation of the cross head is an artist’s impression, of course, and I am sure it looked nothing like this! Centre: A representation of the now badly weathered runic inscription. Right: Line drawings of the cross faces. The reconstructions here show no signs of halos around John the Baptist on the west face (far right of picture) nor around the carving of that of John the Evangelist/Alcfrith. As previously mentioned, I much favour the idea that this lower carving was Alcfrith but the artist’s failure to give a halo to The Baptist either sightly weakens the arguments in Alcfrith’s favour. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote: Alcfrith and St Cyneburgha |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Alcfrith was a son of King Oswiu (or Oswy as it is sometimes represented). Oswiu (AD613-670) was King of Northumbria from AD641 until his death. His early years were spent in exile on the Isle of Iona with his half-brother Oswald where unsurprisingly both became Christians. Oswald in due course snatched the throne of Northumnbria. He was killed by the Mercians at the Battle of Oswestry. Oswiu succeeded him. At the time he took the throne Northumbria was in fact two separate kingdoms - the dominant Bernicia to the north and Deira to the south. Oswiu had King Oswin of Deira assassinated in an effort to unite the Northumbrian throne but he was thwarted when Deira, perhaps unsurprisingly, appointed their own king - Aethelwald who was Oswald’s son. Oswiu, however, had more pressing problems: his perpetual conflict with the powerful Kingdom of Mercia and its pagan King Penda. In an effort to end the wars Oswiu married his son Alcfrith to Penda’s daughter, Cyneburgha or Kyneburgha. It was to no avail, within a year Penda was laying siege to Oswiu’s stronghold at Bamburgh. Oswiu bought Penda off. That also did not buy peace for long and eventually Mercia was defeated at the Battle of Winwaed. Oswiu was at last king of a united Northumbria. You will gather two things from this short account: that the politics of seventh century England involved endless dynastic and territorial wars and that Oswiu did not let Christianity get in the way of ruthless ambition! Oswiu now made Alcfrith King of Deira. Alcfrith fell under the influence of Abbott Wilfrid of Ripon (later St Wilfred) who was the main advocate of the Roman style of Christianity which won the day over the Celtic style at the Synod of Whitby convened by Oswiu in AD664. Alcfrith is also known to have attended but nothing is known of him after this date. We don’t know much more about Alcfrith. Indeed, much confusion arise from the fact he is sometimes known as “Ahlfrith” or “Eahlfrith”. It is thought, however, that he may have tried to usurp his father at some stage and this might explain his disappearance from history. His wife, Cyneburga - later St Cyneburga - went on to found the convent at Castor in modern Cambridgeshire with her sister Cyneswith, also later beatified. It is a long way from Northumbria to Castor so perhaps this happened after Alcfrith’s death. There is a problem here. If Alcfrith was a failed usurper surely this commemoration would not have survived? If he was not a usurper, why did he disappear from history? Bede's Lives of the Abbots states that “Alhfrith” asked his father for permission to accompany Benedict Biscop (see Jarrow and Monkwearmouth) on a pilgrimage to Rome so perhaps Alcfrith/Ahlfrith/Eahlfrith died on his travels? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||