|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

In 1067, inevitably, a Norman – Remigius – was appointed to the bishopric. Eadnoth had completed new transepts and a chancel and by 1073 Remigius had added the nave that is largely unchanged to this day. At that point Remigius moved his see to Lincoln. He decided at this point that Stow should be a monastery and moved some in some monks from Eynsham Abbey in Oxfordshire but they soon returned leaving a distinctly over-sized parish church. It was to get bigger still when Eadnoth’s chancel was replaced by a larger one in the second half of the twelfth century. It seems that there was an expectation that Stow would become an important agricultural centre with four annual markets. This was not to be. In the fifteenth century the tower was rebuilt, the old Saxon one being partly demolished. The roofs were lowered. By the nineteenth century we have the familiar story of dilapidation after the church building Dark Ages of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Even demolition was proposed before the incumbent Rev George Atkinson managed to raise money for its repair and engaged the renowned J.L.Pearson of Truro Cathedral fame to carry out the work. He re-raised and rebuilt the roofs, and rebuilt the east wall completely. What you see today is, then, an almost complete fusion of Saxon and Norman architecture. As you enter your eyes are immediately drawn to the massive central crossing with arches of cathedral-like dimensions. The arch between nave and choir is distinctly Anglo-Saxon. Of course, all four arms of the church are remarkably tall as well, reflecting the Anglo-Saxon love of height in their churches. It really is quite an awe-inspiring place. There are one or two Gothic windows to be seen in the transepts and you can’t ignore the Gothic upper tower, but this is still a church that a Norman would still feel at home in. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

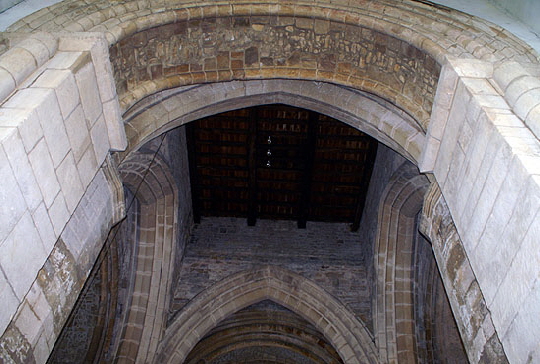

Left: Looking up the church towards the east from opposite the south door. The nearest arch is Anglo-Saxon and if you look carefully you can see another Anglo-Saxon arch beyond that. These supported the original tower. Then, bizarrely, you can see a pointed gothic arch in between. The gothic arches support the present tower that fitted inside the area of the original tower. With the ribs of the chancel vault also visible, this is quite an extraordinary composition. You can see that the nave windows are quite large by Norman standards but nevertheless occupy a small proportion of the lofty walls. As you can see from the external pictures, the windows of the nave and chancel were all placed above a narrow pilaster strip. This strip roughly delineates the surviving level of Aelfnoth’s original church. Don’t imagine that the walls would have been dull. The whitewash we see now replaces what would have certainly been a riot of religious wall painting. With such high walls, this would have been an awe-inspiring sight. In the foreground you can see the unusual thirteenth century font with its distinctly non-Christian images and unusual carved base. More of this anon. Right: The chancel is (although you might not guess it) one of the newer elements of the church, dating “only” from the late twelfth century. This is, however, with the tower the most altered part of the church. The original Norman east windows had been replaced by a thirteenth century Gothic one. The upper east wall, however, had to be completely rebuilt by Pearson who installed faux Norman windows. It is to Pearson’s credit that this is not immediately apparent and you might feel that they added to rather than detracted from the overall appearance of the church. The blind arcading behind the altar is the original Norman. The north and south walls are mainly original but while restoring the roof line to its original height Pearson added an upper course of windows to match those he installed on the east wall. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The view through the crossing towards the west end. Again, the west wall windows are replacements for a fifteenth century perpendicular style gothic one. Centre: The chancel roof has two quadripartite vaults. Pearson had to replace roof completely. A drawing of 1793 shows the roof was made of timber. The ribs of the two vaults Peason built are not identical. Those of the easternmost vault are typical Norman chevron mouldings as are all the transverse ribs. The diagonal ribs of western vault, however, are roll mouldings with bobble-shaped adornments. The Rev Atkinson, rector during Pearson’s restoration recorded that fragments of the original Norman vault had been discovered and were used as patterns for the new one. There is a certain amount of “bodging” in the ribs, so maybe at least some bits of the originals were re-used? Pearson filled the space between the ribs utilising a rather lovely dry stone walling effect. This is certainly a more attractive roof than the one that Pearson replaced! Right: Perhaps even more than the crossing arches, this doorway in the north transept is the biggest give-away of this church’s Anglo-Saxon provenance. You can see the use of “long and short work” techniques on the left hand side and note how the stones pass all the way through the wall and the impost blocks below the arch. This is called “Escomb Style” after a door at the much smaller but even more architecturally important Anglo-Saxon church at Escomb in County Durham. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A section of the Norman blind arcading around the north chancel wall. Right: The strange thirteenth century font. There are two floral devices showing on the bowl and you can see the design that runs around the base of the font, strangely on only three sides. The bowl rests on a rare configuration of one large central pillar and eight surrounding smaller ones. This is probably a very early thirteenth century font and Francis Bond in his celebrated “Fonts and Font Covers” suggests that the treatment of the floral designs is reminiscent of the Normans and that this might be a later twelfth century font. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The remarkable appearance of a green man on a Christian font. Not only is this most incongruous but the face is a distinctly human one and the man is wearing a hat! I have seen nothing quite like it elsewhere. Centre: Next to the green man is a pentagram. It is crudely drawn but the star is drawn with overlapping arms - on paper you could draw this with just five strokes of a pencil. The pentagram has had many symbolic meanings since ancient times and, certainly in recent times, not all of them positive. The “sculptor” here might be simply using it as decoration. In Christianity it represents the five wounds of Christ, which would be the obvious answer here were it not for the other distinctly bizarre motifs. At the most esoteric, Neoplatonists (and I am not going to begin to try to talk about them!) used it a symbol of “health”. If you read about Mary Curtis Webb’s work this is not as far-fetched as it might seem but our sculptor hardly seems to have been a man of a philosophical bent! Right: Then we have a little monster of some sort. All very odd. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

More pictures of the font. Top Left: The bowl with the monster and an another foliate motif. Note the damaged leaf carvings at the bottom of the bowl that suggest to me that the whole thing has been messed about with some time in the past. Those eight pillars look suspiciously “modern” compared with the rest of the font! Top Right: The very unusual carving around the base of the font. The only explanation I have suggested is the very plausible one that that the elongated figure is meant to be a dragon - evil - which will be defeated by the sacrament of baptism. This very Christian idea is, depending on your interpretation, a contradiction with the arguably pagan images on the bowl or else an indication that they do indeed have Christian provenance. Certainly, this font reinforces the mystery of the ubiquity and ambivalence of green man image in Christian churches. I will throw in a bit of speculation of my own: I don’t believe that the base and the bowl were carved by the same man. The base carvings look a little more sophisticated to me. The bowl looks to have been carved by someone who had little experience or knowledge of what he was doing. The base looks more sophisticated and the the whole thing - look at those round “sockets” for the pillars - is quite nicely executed. Make up your own mind. Lower Left: A weathered human face. A soul to be saved? Lower Right: Possibly the Devil’s face. It is quite detailed. One more piece of speculation: why are the base carvings weathered? I wonder if this is yet another early font that was shoved out into the churchyard to rot and rescued at a later date? That would explain the damaged bowl as well. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The north transept houses this altar with a Norman arched surround. On the wall are the remains of a twelfth or early thirteenth century painting of the murdered Thomas a Becket. It was, therefore, only a few decades after the incident itself on 29 December 1170. Sadly, even since its re-discovery in 1865 material has been lost. The pity is that such survivals are rare: Henry VIII decanonised him after he had declared himself head of the Church of England and ordered images of him to be destroyed. It is not hard to see why. In his quarrels with Henry II Becket had epitomised the struggle for supremacy between Church and Monarchy. The last Henry brooked no such arguments. Right: Even this fragment shows that this was a high quality piece of art. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

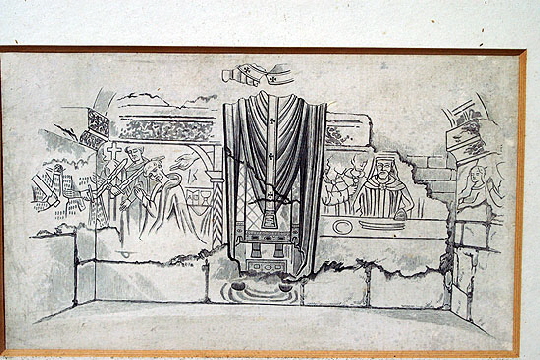

Left: A reproduction of the painting as it was before the more recent deterioration. Right: This is my favourite thing in the whole church and is found on the north side of the chancel arch.. It is the earliest known representation of a Viking longship to be found in England. It is tenth or eleventh century and the Church Guide speculates that it “may be the work of a Scandinavian trader or marauder who had sailed up the nearby Trent. Why, one might wonder, would a Viking take time out to scratch out this graffito within a Christian church? I wonder if it is not just as plausible that a member of the local population - perhaps a child - carved it as some kind of record of a raid? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This picture shows the square grouping of pointed arches that sit inside the original Anglo-Saxon crossing and support the perpendicular tower of about AD1400. Right: Pearson’s reconstructed chancel. The south wall is original, the east is not - see above. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

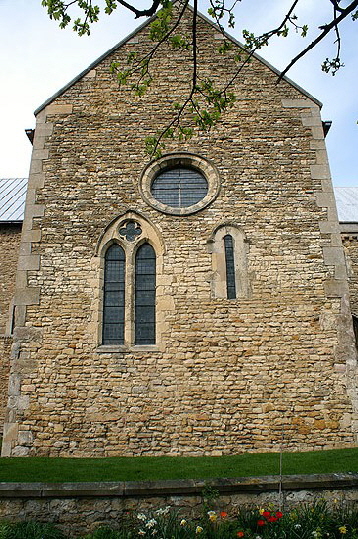

Left and Centre: The south transept with a rather remarkable group pf windows. The narrow window is Anglo-Saxon. The round window is Norman. The gothic window is superficially uninteresting but in fact it is a fine example of an Early English window. The masons had not yet mastered the art of complex tracery so they would simply cut through the stone (in this case a quatrefoil) in a technique known now as “plate tracery”. Right: A mediaeval bench end. |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The south transept nglo-Saxon window. It is surrounded by massive masonry blocks. The hood mould have a crude “palmette” decoration. Some of the blocks have dowel holes showing but I don’t know what these were for. Centre: A pair of Norman windows in the south side of the chancel. Right: The west end. The windows date from Pearson’s rebuilding but the Norman west door is original. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Stow has two substantial Norman doorways, both with four orders of very restrained ornamentation, and neither with tympani nor extravagantly carved capitals. Left: The west door, now disused. Right: The south door has survived the ravages of time rather better - our climate is much kinder to south walls than to the west. I believe though that some of the decoration has been re--cut. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Capitals from the west door - with very obvious signs of refurbishment top left. Right: The church from the south east. Both courses of chancel window are Norman. Note, however, the decorative strip at the top of the chancel wall that was out there by Pearson when he raised the roofline. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The east end. Pearson’s rebuilding of the east wall is very sympathetic to the Norman side walls. Right: A nice little group of carved faces in the south transept.. The Church Guide suggests that they are fifteenth century and were used to support a statue. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

These two rather crudely carved musicians support a stone shelf in the north transept. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

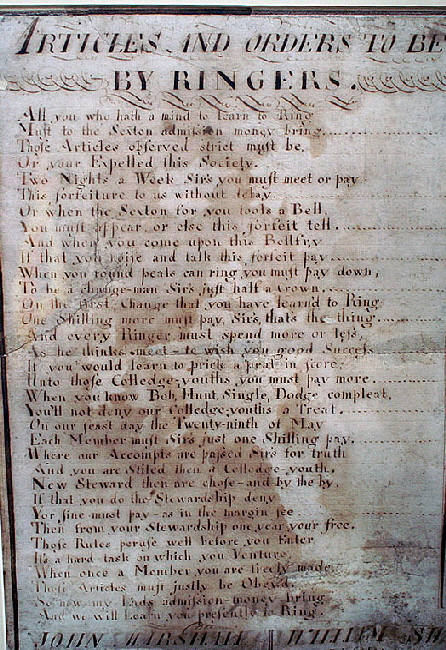

Left: English churches are just full of historical delights. This document outlines “Articles and Orders to be Observed by Ringers” and (sorry - out of shot on the right) the many payments and fines you might have to make! Bell ringers of my acquaintance are mainly there for the beer! Upper Centre and Right: The tower has wonderful birds and griffons to protect it. They in turn are protected from birds by nasty-looking metal spikes. As you can see from the right hand picture the spikes are not wholly successful. Lower Centre and Right: There are gargoyles on each side of the tower. Strictly speaking they are not gargoyles at all because they are not there to take water from the roof; but in the later gothic period such carvings were often just added for fun. The left hand figure (a very long way up, let me tell you!) is of a monster carrying some sort of creature on his back. I haven’t seen this device outside the area described in my book “Demon Carvers & Mooning Men”. In my book I call them “piggy back gargoyles” and all six I have found were carved by a man I call the Gargoyle Master. This one at Stow is not by him, of course, and the design is different. Still it a salutary warning against over-use of the word “unique” where our parish churches are concerned! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Now go to Coates-by-Stow |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Stow is A VERY BIG IMPORTANT CHURCH even though most people have never heard of it! When I have been to a VBIC I always delight in visiting a very small unassuming church on the same day. It kind of puts things into a better perspective. While the bishops were wearing their finery and preaching to the gentry in places like Stow, countless long-forgotten rectors were earnestly haranguing peasants and farm labourers up and down the land at innumerable little parish churches. One such is Coates-by-Stow. It’s what I call a “farmyard church” because it feels like it’s just an outbuilding of the nearby farm. It’s tiny, it’s fascinating and it’s rather lovely. For most of us this is the sort of place our ancestors worshipped. It is just three miles from Stow-in-Lindsey and it would be a travesty for you to visit one without the other. Do include it on your itinerary. Have a look at its webpage on my site by clicking here: Coates-by-Stow. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||