|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

cell structure with a comparatively small chancel. There is nothing of the“Romanesque” about it and so, unlike its famous neighbours at Jarrow and Monkwearmouth, it too probably had its roots in the Irish Celtic tradition brought to these shores by St Aidan. Jarrow and Monkwearmouth - the so-called “twin monastery” was built by Benedict Biscop who, along with his friend St Wilfred, was an arch proponent of Roman liturgy and architecture and who consciously copied Romanesque architectural styles. The same is true of the Kentish nexus of churches sponsored by St Augustine in the late 6th century. One might then make the case that Escomb is the oldest church we have that is of singularly British design. Moreover, it is more or less unchanged. With its relative obscurity, Escomb has none of the “Bede’s World” hype that is associated with the twin monastery. There you will find a profusion of story boards and an enormous wealth of historical analysis and archaeological “finds” . At Escomb you collect the key from a nearby house, let yourself in and enjoy the church in splendid solitude! None of this, by the way, is to detract from those other sites which are essential to an understanding of Anglo-Saxon monasticism and spirituality: if you visit Escomb you should surely visit them too. The church is of enormous and disproportionate height, even by the standards of Anglo-Saxon churches. We don’t know why this was so, but perhaps it was part of the long-established tradition of moving the building nearer to God. The upper courses of stone are noticebly smaller. You might postulate a very simple explanation that smaller stones were easier to lift to such a height. Yet the same is true of the much lower chancel. I have never seen it suggested by anyone else, but I wonder if the walls were raised at some point? The chancel is as shallow as the chancel is tall and just a little narrower. Much of the stone was recovered from abandoned Roman buildings - and bear in mind that this part of England south of Hadrian’s Wall would have been heavily militarised. This explains the profusion of stones inscribed with decorative patterns and even, in one or two places, with legionary inscriptions. The criss-cross pattern (“diamond broaching”) on many was a Roman device to facilitate easier plastering. These probably came from the nearby cavalry fort at Vinovium (now Binchester). There is even speculation that the church is a remodelled Roman building. The chancel arch itself is also believed to be a reconstructed Roman one and it mortarless, a testimony to the accuracy of the carving. Supporting the chancel arch are two courses of typical Anglo-Saxon “long and short work”. Interestingly, this feature is rather rare in Northumberland Anglo-Saxon architecture and is not even used in the quoins between chancel and nave at Escomb. itself. Only 5 of the windows are original. The two on the south side have rounded tops carved from massive pieces of stone. They are deeply splayed within. The two on the north side are different: they are rectangular with lintel stones. Why are they different? The two north doors are also rectangular with lintels. High on the west wall is another original window. On the west wall you can also see a roofline where once there was a two-storey extension to the church. There is speculation that this was used to house the clergy and that there night have been a crypt below. It is now believed, however, that an internal gallery at first floor level was a common feature of Anglo-Saxon churches: Deerhurst, Brixworth, Jarrow and Monkwearmouth amongst them. There is no sign of a doorway in the wall, but is it possible that Escomb also had such a gallery with access from the extension? Stone from this part of the building is believed to have been used in the construction of the c13 porch. Simon Jenkins gives Escomb two stars (as he does to Jarrow). How he ranks it lower than a multitude of gothic churches distinguished mainly by their funerary monuments is a mystery to me! To visit Escomb is to step back in time. Visit it, savour its antiquity, drink in the extraordinary atmosphere of ancient spirituality. |

|

|

||||

|

|

|||||

|

Left: Looking towards the east. Note the height and narrowness of the chancel arch. To the left is an original north door. Right: Looking towards the west. The lower window is of c19. The upper window is original Anglo-Saxon. Try to imagine how dark this church would have been with only its original windows and with a two-storey extension to the west!. |

|||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

Left: The soffit of the chancel arch has traces of painting. This was believed to have been of around the Norman period, but similarities with paintwork at Jarrow has raised the question as to whether it is fact Anglo-Saxon. Right: The Anglo-Saxon font is of sufficient proportions to allow the total immersion of infants. |

||||||

|

|

|||||

|

Left: The south wall showing the splays to the Anglo-Saxon windows. Right: The original consecration cross behind the pulpit and to the left of the chancel arch. Again, the form of this cross indicates Celtic provenance. |

|

|

||||

|

|||||

|

Left: This cross is mounted behind the altar. It is believed to be c9 and could well have been a coffin cover. Another theory is that it was a “preaching cross” used before the church was built. Centre and Right: These fragments of a stone cross are mounted inside the porch. One fragment has a rather superb representation of a bird. |

|

|

||||

|

|||||

|

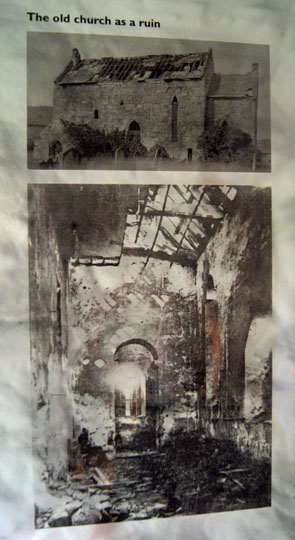

Left: This grave slab in the chancel is of “frosterley marble” and must have been made for someone important. There are no British marbles so this, like all of the other pseudo-marbles, is actually limestone and is packed with fossilised corals. Frosterley is in Weardale about 20 miles west of Durham (in whose cathedral is was also used) north west and 15 miles north-west of Escomb. Centre: Also in the chancel at its north-west corner is a blocked up doorway which once connected to a vestry. On the right hand jamb is carving that has been suggested as being Adam and Eve below the Tree of Life. Right: I reproduce one of the church’s (very informative) boards which shows how the church looked before it s rescue between 1875 and 1880. The Rev Thomas Lord realised its historical significance and together with his parishioners restored it. Ironically, the Victorian church at the top of the town that replaced it has now gone! I make many slighting references on this website to Victorian “restorers”, many of whom were more akin to well-intentioned vandals, but Escomb is one of a number of churches that would no longer exist without intervention by men and women at that time. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

|

||||

|

(Left) One of the superb arched Anglo-Saxon windows on the south wall surrounded by just four stones. Note the massive top block. Also to the left is yet another stone with “diamond broaching. (Centre) At the quoin between the chancel and the south wall we see massive stone blocks laid edge on edge. This is known as “Escomb Style” and is used here in a position where many Anglo-Saxon churches would have had “long and short work”. For an example of the latter see Wittering in Cambridgeshire. In the picture (Right), ironically, we can see that the chancel arch at Escomb is supported by long and short work - a comparitive rarity in the Northumbrian Saxon school but common in the southern Saxon churches. |

|

|||||

|

|

||||

|

Left: The west end with the roofline of the original two storey extension. The west window is c19. Centre: The north door from the chancel - see above for interior pictures. Right: The north door from the nave with its lintel and massive side blocks. |

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

Left: The north side of the church. Note the rectangular windows and contrast them with the arched ones on the south side. Right: The porch is “new”, being only c13, but even this uses stone from the old west extension. Note the sundial over the porch and the other top left of thw window. |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Left: This extraordinary sun dial is the oldest in Britain that is still in its original place. It dates from c7 or c8. A beast’s head surmounts it. Around the outside is a serpent. Only three lines are visible, presumably showing the times of prayer. There are numerous theories about the iconography and you should acquire the very detailed leaflet sold in the Church. Whatever its provenance, this is an extraordinary treasure on an extraordinary church! Right: The Anglo-Saxon cross mounted on the porch gable. |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Left: I’m afraid it’s impossible to discern from this photograph, but this stone high on the north wall is inscribed “LEG VI” for the 6th Roman Legion. The decoration at the bottom is somewhat easier to see. Such stones abound in this part of England, especially around the wall. This one has been incorporated into the church (upside down!). Right: And finally...no this is not at Anglo-Saxon tombstone. But this is one of two with crude skull and crossbones imagery. There is nothing unusual about that but I added this photograph because I don’t remember a cruder tombstone - and I seen a few, believe me! |

||||||||||||||

|

Footnote - Escomb as a Living Church |

||||||||||||||

|

Diana found this information on an American holiday website www.gadling.com. I am reproducing it here with acknowledgment to its author Sean McLachlan: a fine British or Irish name if ever I heard one! |

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||