|

|

Alphabetical List

|

|

|

County List and Topics

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Oakham is the county town of Rutland: a small county town for England’s smallest county! Its church is Gothic throughout and was restored by the ubiquitous George Gilbert Scott in Victorian times. That should set anyone’s alarm bells ringing; but in fact Oakham is one of the most visually satisfying of town churches.

The church was constructed almost entirely in late the later thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries but is on the site of an earlier church of around AD1200. Its principal glory is the capitals of the gothic nave that recall the riotous imagery of the Romanesque period. On the north arcade we see more worldly images : the fall of Adam & Eve, a Green Man, and grotesque heads. On the south side are angels, saints and Reynard the Fox! Worthy as the images are on the south side, I think that as in so many things the Devil has the best Capitals! Each spandrel has a carved face.

The font is late Norman, dating from about 1180. The entrance porch on the south wall is Early English dating from around 1200. The aisles are from the late thirteenth century but their walls were raised in around 1400, thus making room for the large Perpendicular-period windows that we see today. The west window of the south aisle is, however, Decorated.

Architecturally, Oakham is not of major interest apart from those capitals. it is, however, a very satisfying church visually. The style is reasonably consistent and symmetrical, avoiding the architectural “bugger’s muddle”

|

|

|

|

|

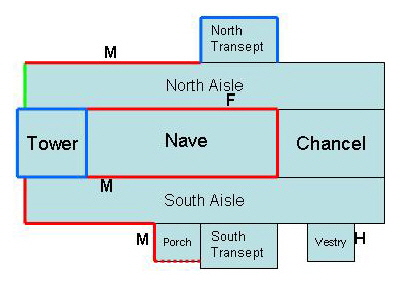

Oakham Church and the Mooning Men Group of Masons

Much ink has been consumed talking about the nave capitals, of which the church is justly proud. Oddly, few writers, if any, mention the extensive sculpted friezes that are beneath almost every roofline of this extensive church. The gargoyles too get little attention. This church, however, is the geographical and arguably the stylistic epicentre of the mass of work that was executed by what I call the “Mooning Men Group” of stonemasons. If you are unfamiliar with my work on this previously-unidentified group then you can read about it on this website here.

Simon Jenkins refers to the capitals as “Decorated” and I wonder what he means by this? Decorated with a small “d” is a truism. But if he means of the Decorated style or period and this is nonsense. There was no distinct style of Decorated capitals. The Decorated style overlapped substantially with Perpendicular style so there was no discrete Decorated period in the way we think of Norman and Early English. So I think he means the pre-Plague period - that is the first half - of the fourteenth century. And I think he is wrong! The Church Guide talks of a rebuilding in 1400 and the capitals are surely of that time when the aisles were being widened and the clerestory raised. I have commented several times in my account of the MMG that such work inevitably resulted in the re-profiling of arcade arches (although not usually of the columns) to accommodate the new geometry and the new lighting of a church. We get evidence at Oakham - as at other churches in the area - in the spandrels where faces are carved, some wearing the ladies goffered caul headdress that is so characteristic of that time and a much-favoured trope of MMG sculpture.

Needless to say, we see the goffered caul headdress in abundance on the church’s friezes as well. Those friezes are in the main carved by the mason I named John Oakham because of his prolific output here. You can see his work at many churches between here and Boston on the Lincolnshire coast. 7

|

|

|

|

|

|

On the south west aisle wall we see also the work of Ralf of Ryhall whom I named for his prolific output at Ryhall Church thirteen miles to the east. It was Ralf’s obvious appearance at both churches that started my investigations and led to the whole emergence of the Mooning Men Group.

Oakham weighs in with no fewer than three mooner carvings, the trademark of what was clearly a peripatetic group of masons or - more likely - of the contractor-mason that employed them all in various combinations. Here too we see and example of the “flea” carving that is also prolific and seems to be the personal trademark of John Oakham.

On the south side chapel we see also two very characteristic gargoyles by the man I call the Gargoyle Master. One of them is one of the six iconic “hitchhiker gargoyles” that were bequeathed to us by this man. So we can identify three MMG masons at Oakham: John, Ralf and the Gargoyle Master. Fascinatingly, on the north side and, as far I know hitherto unremarked, is a gargoyle - what seems to be a rare female gargoyle - clutching a horseshoe to her breast. This is an obvious reference to the de Ferrers family who had been given the estate by the Conqueror. Ferrer is derived from the French “Ferrier” or farrier, hence the horseshoe symbolism. The nearby Norman Oakham Castle (actually a Norman hall) has numerous horseshoes on its walls presented by its distinguished visitors, a practice started by Edward IV in 1470 after the nearby Battle of Losecoat Field during the Wars of the Roses. So this gargoyle imagery actually pre-dates that custom. The joke, it seems, was a very old one and the Oakham castle custom continues to this day.

These men were not here just to prettify the church with sculpture; that was incidental. In what must have been an extremely expensive remodelling of the church they did all of these things: widened the aisles reprofiled their arcades and made their roof pitches shallower (to see why this was inevitable follow this link); built the clerestory; leaded all of the roofs; installed battlemented parapets (to conceal the ugly lead); installed cornicing below these parapets and gave then sculpted friezes; installed gargoyles and drainpipes to clear rainwater from behind these new parapets/ They almost certainly built the top stage of the tower (it would have been far too tall for the church before it gained its clerestory) and the spire. It would all have cost a fortune and the excellent Church Guide says it was all funded by Westminster Abbey who had received a huge bequest from Simon de Langham who had been Archbishop of Canterbury (and declined a second term in that office) and Treasurer of England. Ooh, I wonder how he came to have so much money...? Langham is only two miles from Oakham. Its church too is magnificent and another where the MMG - and John Oakham - worked.

|

|

|

|

Top Left and Top Right: Looking east and west respectively, there is a lovely symmetry to the nave with gothic arcades on both sides. The west wall shows the original nave roof line before it and the walls of the aisles were raised and the clerestory installed in around 1400. Interestingly, the porch at the west end of the church is Early English in style dating from 1190, and is this the oldest extant part of the church.

Centre Right: The chancel with its Victorian east window and three-bay arcades leading to the chapels to the north and south. George Gilbert Scott was apparently criticised for their being Decorated rather than Perpendicular in character, a rather strange complaint considering the atrocities he committed elsewhere. It looks fine to me, and anyway the trefoil and quatrefoil tracery is surely much more attractive than the almost cliched typical Perpendicular east window?

Lower Left: The Lady Chapel of the south aisle dates from the 1480 and is a fine example of the Perpendicular style. Does any reader, however, prefer its east window (again, a fine example) to Gilbert Scott’s chancel window? The arcade through to the chancel is also Perpendicular.

Lower Right: Looking across from the south aisle towards the chancel and North chapel - a veritable mass of arches but all fitting very harmoniously and making for a splendid church aesthetically.

|

|

|

|

The Arcade Capitals

|

|

|

|

Left: The southern capital of the chancel arch has a quite exceptional array of carving (and it is worth comparing it with that of its northern counterpart (above). Here we seem to have a king either crowning his queen or else patting her on the head! In fact it represents the coronation by God of the Virgin Mary - the Annunciation. Right: The theme is continued by an angel on the left and what appears to be another Adam and Eve tableau.

|

|

|

|

Left: The south side offers us one of the little mysteries at Oakham. There are a number of capitals that purport to show either the legend of Reynard the Fox or Chaucer’s Nun’s Priests Tale - nobody seems to know! Just to confuse things it is known that Chaucer used parts of the Reynard legend in his Nun’s Priest's Tale. The only I thing I will say is that the Reynard story is long and involved and I actually can’t find a reference to the stealing of a chicken. I suspect what we are seeing is just another English folk tale that Chaucer adapted. The Canterbury Tales were first published in the 1390s so it is bang in line with the likely time frame for the church’s rebuilding programme. Would the masons have seen or heard stories from the Tales fifty years before the invention of the printing press? No, I don’t think so either! Foxes nabbing chickens is hardly a rare story, is it|? This particular picture seems to me to clearly show a fox running off with a chicken while to the right is the beginning of a human face - see the photograph to the right. Right: Life is too short to spend time boning up on Reynard and Chaucer if indeed the story is from either so I don’t know the significance of this rather jocund looking man with a chain around his neck with what looks like a heavy weight attached

|

|

|

|

Left and Right: This rather peculiar capital feature faces with fringed veils - we have to presume they are women - some with animalistic legs.

|

|

|

|

Left: A rather peculiar composition of a bull with improbably small wings. This the traditional representation of St Luke. The other three evangelists are also represented. Right: St John represented as an eagle.

|

|

|

|

Left: Another look at “Reynard” - any resemblance to a fox is purely coincidental. Something worth noting is that the chicken (or whatever) is not actually in his mouth. The bird’s head looks to be alive and pecking while two other birds - presumably his chicks - are attacking his tail and hindquarters with some vigour. Is it Reynard? You decide. Right: This is the scene to the left of the “Reynard” scene (ie to the left of the left hand picture). If you look carefully the beast is actually being attacked not by two birds but by five, three of which are visible here. The woman to the left appears to have probably a broomstick in her two hands but I am at a loss to know what she has apparently hanging from her hand at the bottom of the sculpture. A distaff (for winding wool) possibly?

|

|

|

|

Left: We are on safe ground here. This is a “pelican in her piety” feeding (as legend would have it) her young with blood from her pecked breast. A popular mediaeval image with no zoological foundation whatsoever! Right: Grotesque corbel supporting the nave roof.

|

|

|

|

Left: The reredos of 1895. Right: The west corner of the south aisle. The picture shows how richly endowed the church is with external carvings. You can see the frieze (by John Oakham), pinnacle carvings with grotesques and a gargoyle at the corner. If you look at the eye structures and some of the headgear you should get the same sense as I do that these were carved by whoever carved those arcade capitals and spandrel carvings inside. Were they also by John Oakham?

|

|

|

|

Left: One of the few things not aesthetically pleasing about Oakham Church are the off-centre bell openings of the tower.. As Pevsner put it : “distressingly out of the centre line of the tower to allow for the staircase”. The balustrade has three ogee-arched openings on each side. This is the same design as the top stage as Whissendine Church - another MMG site - less than five miles away. Right: There are three niches on the west side of the tower, each still having its original statue of (from left to right), St Peter, Christ and St Paul.

|

|

|

|

On the vestry on the south side of the church is this gorgeous example of what I call the “hitchhiker” gargoyle carved by the man I call the Gargoyle Master. It is one of six that survive, A woman in goffered caul headdress sits astride and seemingly steers the somewhat disconcerted looking beast below here. Between the beast’s legs - not very clear here - is another woman’s head with the goffered caul.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left: This other Gargoyle Master is on the opposite side of the vestry from the hitchhiker. Less iconic than its partner, this one nevertheless shows another recurring Gargoyle Master trope: the odd little bat-like wings behind the head. Right: Two of the short run of Ralf of Ryhall carvings on the west end of the north aisle. They are very clearly from the same sculptural stable as those on the south west of Ryhall Church. You can see that here, as at Ryhall, Ralf made use of lead for eyes, although both carvings have lost one. The Gargoyle Master also used lead for eyes. Look at the wavy fur on these two grotesques and compare it with the wavy fur on the hitchhiker gargoyle. Could Ralf and the Gargoyle Master be one and the same man?

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Oakham’s four Mooning men Group icons. Three different mooners - the trademark of the whole group and (far right) a somewhat battered “flea” carving, the personal symbol of John Oakham.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lengths of Oakham Frieze. Rows One and Two: North aisle. Rows Three and Four: North Clerestory Row Five: East clerestory. Rows Six and Seven: North Clerestory Row Eight: North Transept.

There is a lot to take in here, but there is a very clear single overall sculptural style here that contrasts with the more imaginative grotesques of Ralf of Ryhall (below). The style is largely but not entirely consistent. This is the unmistakable trademark style of John Oakham which is seen to even better advantage at Brant Broughton over thirty miles away. John was the only one of the MMG masons who apparently was prepared to wander far from home as far away as Boston on the Lincolnshire coast. The slight variations in eye detail lead to my speculation that John Oakham shared some of the frieze-work here with a regular and less skilled collaborator - “Simon Cottesmore”. But there is no certainty. Either way, John set the tone here. The north transept frieze is in the same spirit as the rest of the church but unaccountably it is narrower and less densely populated. Simon Cottesmore might be a candidate for this too but again there is no firm evidence.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The full set of Ralf of Ryhall’s frieze on the west end of the north aisle.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The south porch frieze, south side. The porch is believed to be earlier than fifteenth century so the frieze must be a product of the re-roofing exercise. This is the most intriguing of the friezes attributable to John Oakham. It is densely packed and the style on the left side of the gable looks to be slightly different to that on the right. It is worth looking at how the cornice is pieced together. Some lengths have one sculpture anbd some have two. Where there are two it tends to be one grotesque and one fleuron and this is the general - but not invariable - pattern at Oakham and elsewhere in the MMG. This means that it is relatively simple for more than one sculptor to be working on a long run of cornice and we often cannot assume that AN mason does not somewhere intrude. The domestic dog (far left) is quite popular with the MMG. At Fotheringhay in Northamptonshire the domestic dog is widely believed to represent the master mason’s own pet. It could be true. Note the goffered caul headdress next to the dog.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

What should be the collective noun for a group of gargoyles? An “outpouring”? A “flood”? I think maybe a “gush”. Anyway, here are six more gargoyles. The eyes structures here - apart from the far right on the bottom row - have the humanistic appearance that ties them somewhat to the nave capitals and arcade spandrels. Look now at the gargoyle top left. He has a head between his legs. These are normally the speciality of Gargoyle Master but look at that head with the fringe. That is, again, similar to what we see on the nave capitals. Whereas the gargoyle bottom right is at the east corner of the south aisle. This gargoyle has those little batwings - see the larger picture above - and black lead eyes. This one is indisputably by the Gargoyle Master.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The top stage of the tower, built by the MMG. There are two gargoyles on each cardinal point. The MMG usually used the cardinal points rather than the corner. All of the carvings, including gargoyles, seem to be by different sculptors from those who worked on the ground level. It would be hardly surprising if the tower was progressed separately from the lower levels where there would have been a lot of critical path project planning - as I am sure they didn’t call it! The octagonal turrets at each corner are also found at nearby Exton. There the turrets are battlemented rather than having conical tops. Interestingly, though, at both churches there are friezes with lots of ballflower carving which would have been “retro” when this work was done.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left: One of the turrets with ballflower decoration and grotesque heads at the angles. Right: The north side of the north transept. Again, you can see that there is another narrow cornice frieze. It cannot be emphasised too often that such friezes were not necessarily concurrent with the building of a structure. In fact they were very rarely were except in the case of clerestories. The leading of roofs, changes to rooflines, the insertion of larger windows and especially the widening of aisles all gave opportunities for the addition of roofline decoration and gargoyles.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left: The south aisle flanking the chancel. It was remodelled by George Gilbert Scott, a statement that it sufficient to strike fear into any church crawler’s heart. Apparently, though, the chancel had fallen into decay during the seventeenth century and we can’t begrudge the Victorians their many acts of salvage, of which this surely was one. You can’t take exception to it: it is classic bland military-medium high gothic. Did Gilbert Scott remove sculpted cornice from the roofs? On the whole, I think not. But we have, as so often is the case, a mystery. The side building to the right is a vestry. Nobody seems very sure when it was built and, of course, remodelling by Gilbert Scott may have muddied the waters. I have seen sixteenth century quoted for this vestry. Yet it is on this very structure that the Gargoyle Master’s two little masterpieces are found, including the hitchhiker. How to explain this? Well, it could be that my dating of all this MMG work is wrong. Which means my dating via the goffered caul headdress is wrong and that numerous churches have the wrong dates for their clerestories, aisles and towers. Bear in mind also that there is a Gargoyle Master gargoyle on the west end of the south porch. At the risk of hubris, there is no chance this could be so. So we are left with two possibilities: that the dating of the vestry is incorrect or that Gilbert Scott recognised the quality of the gargoyles and moved them, perhaps from the original aisle roofline. In support of this last theory is that the vestry roofline has no cornice friezes. Why would they have been missed out on this part of the church alone if the MMG had built it in the early fifteenth century? This mystery has been bugging me for ten years! Right: The church from he south east. Here you can see the grandiose triple east end with aisles that extend as far as the chancel. At Oakham this is also true of the west end such that except for the excrescences of transepts and chapels this is a fundamentally rectangular church. Gilbert Scott’s east windows. The Church Guide says that thy were not well-received by the public, who felt that they were of designs unnecessarily anachronistic with the mediaeval core.

|

|