|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

it has a blocked doorway on its outer wall that is clearly from that period. Equally, study of the masonry on the east end of the south aisle shows that it was made wider at some future date to match the width of the north aisle. Beyond that, Youlgreave represents a pretty typical hotchpotch of styles that evolved over 300 years of the gothic period. The west end of the nave, the south porch and the west tower are fifteenth century. The chancel is fourteenth century and will have replaced an original Norman one. The south aisle, as we have seen, was widened in the the same century. Some restoration occurred during the Victorian period, especially in the chancel. The fabric of this church will not enthral the experienced visitor, however, and it is to its furnishings we must look to justify our visit. Most conspicuous is the very peculiar and surely unique Norman font. It has a stoup for either holy water or oil built into one of its sides. It has a couple of quite elaborate and well-carved designs around the bowl but of much more interest is the carving of an inverted salamander on one side of the bottom of the bowl! It is a safe bet that the mason had never seen a salamander in the flesh but it is represented in the mediaeval bestiaries - see the footnote below. In ancient mythology the salamander was believed to be fireproof and came to represent the ability to resist the fires of sin. Thus it came to be seen as a symbol of baptism. The second Norman treasure of note is a Norman carving of a human figure set into the north wall. the figure carries a staff and a pouch and is believed to represent a pilgrim. It has to have been moved to this position since this is a fifteenth century piece of wall, but nobody knows from where. The roof has some particularly interesting and vibrant wooden carvings. There are are a couple of tombs that even I find interesting (and which, predictably, Simon Jenkins sees as the main reason for coming here!). All round it’s an interesting place: one of those pleasing churches that has you continually looking into the (excellent) Church Guide to answer “what’s that then?”. Let’s take a look. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

Left: The view to the east end. The font is to the right near the south door. Note the round late Norman arches of the south arcade and the slightly pointed Transitional ones to the north. The chancel arch is fourteenth century. Right: The view to the west end. The impressively-proportioned tower arch gives an unencumbered passage for light from the west window. All fo the nave beyond the arcade is fifteenth century, including the tower. With a substantial clerestory, this is a church well able to make use of the strong summer sunlight we were (for once!) experiencing that day. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

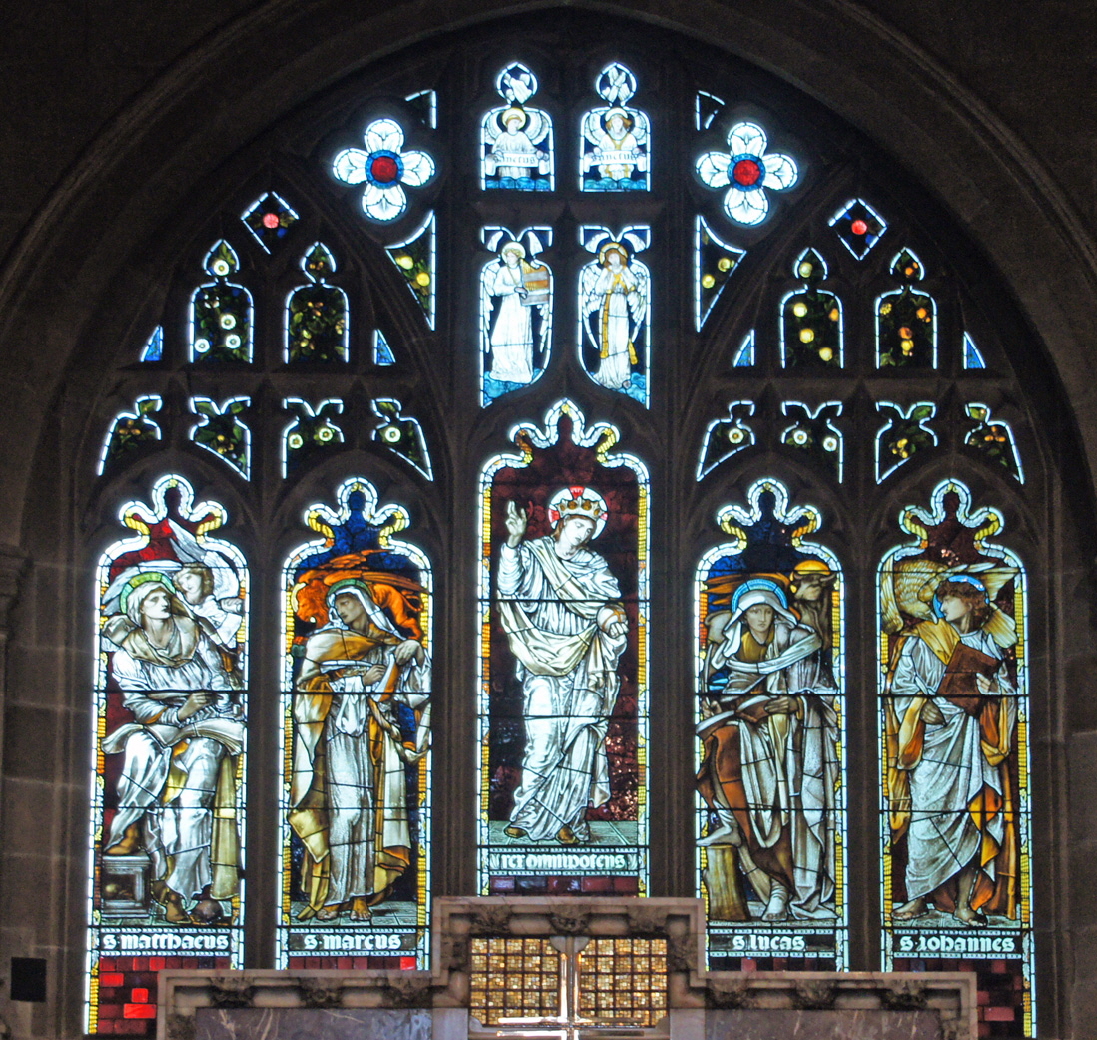

Left: The chancel is fifteenth century but the east window is by the pre-Raphaelite painter and stained-glass maker, Edward Burne-Jones who was also a member of the Arts & Crafts movement. William Morris’s factory produced it and Morris also contributed to the window itself. You will see a bigger picture below. Right: The Transitional north aisle. The rectangular windows are Victorian replacements. In the east window window we see another example of glass of a distinctly superior kind - this time by Charles Kempe, made in 1883. It is dedicated to the memory of one Thomas Teasdale. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The Norman south aisle looking west. The capitals are plain scallops in the later Norman style. Right: The columns of the transitional period north aisle are rather slimmer than their southern Norman counterparts, a trend that would continue throughout the gothic period. The capitals are square in profile with volutes (curly bits at the corners in the Greek doric style). This one has a nice green something-or-other. Not a green man with those ears and not that good old stand-by the green cat. This one looks a bit like a green dog! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The Norman pilgrim figure on the north wall. Centre: Now this is a peculiarity. Someone has clearly recognised that this fragment is of interest. I have found that I am not alone in speculating that it is Anglo-Saxon in origin. Yet it is roundly ignored in all of the literature! As I am wont to do when I am verifying my own assumptions, I asked Diana what she thought this was. She said “a man with his back to us, weeing in the bushes”. <sigh> Sometimes she just doesn’t treat this stuff with the respect it deserves...All sensible alternative theories would be welcomed! Right: I’m always a bit sniffy about the aristocracy sequestering our churches as own personal family mausoleums but even I have to admit that this handsome piece adds something. This is Thomas Cockayne who, to quote the church guide, “died in a fight with Thomas Burdett at Pooley Park in Warwickshire while they were both on their way to Polesworth Church”. They quarrelled over a family marriage settlement”. Because he died before his father, his effigy is small. It was found in a barn and placed here slap bang in the middle of the choir in 1873. Vicars ever since must have been thrilled! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The font. Left: The inverted salamander creeps towards the stoup. No salamander ever had legs and tail like this but the symbolism seems compelling since this is the only such carving on the font. Right: The font from the east side, showing one of the foliate carvings which are themselves far from conventional. The only date I have seen attributed to it is AD1200. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This little piscina is in the north aisle. The Church Guide reckons it was moved here from the south aisle. The head looks Norman. Right: The alabaster reredos of the north aisle altar. It is a memorial to Roger Gilbert of Youlgreave from the late fifteenth century. It, again, is believed to have originally placed in the south aisle lady chapel. This would make sense as the centre piece is a figure of the Virgin Mary. The inscription says that Gilbert “caused this chapel to be made”. Marian imagery and chantry chapels in general were under attack during the Reformation so this might account for its being moved. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There are some nice roof bosses on the fifteenth century roof. Left: a pair of back to back monsters. Right: A tongue-poking bear. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This man looks like he has been impaled but I am sure the imagery is accidental! Right: This blocked transitional style north aisle doorway is proof that the whole aisle dates from this period, unlike the south aisle that was widened beyond its Norman plan. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Edward Burne-Jones’s east window showing Christ and the four Evangelists. The pre-Raphaelite artistic style is very obvious. The four angels in the upper lights were the work of William Morris himself. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote - Edward Burne-Jones |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98) was an artist and member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. He was born and educated in Birmingham. At Exeter College, Oxford he became friends with his fellow student, William Morris who will be forever remembered as the leading light of the Arts & Crafts movement. .Together with a small group of friends, Burne-Jones and Morris formed the “Birmingham Set”. Amongst their activities was visiting mediaeval churches. Burne-Jones’s early work was very influenced by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the founder of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Burne-Jones, Morris and Rosetti’s married lives seem to have become somewhat (ahem) entangled! Burne-Jones’s early work was mostly of watercolours and he was not conspicuously successful. A switch to oils saw his star rise in 1877. He developed a yen for vibrant colours. In 1885 he was elected Associate of the Royal Academy and exhibited at the RA in the following year. In 1893, at the prompting of Gladstone, he accepted a baronetcy. He described his approach to painting thus: “I mean by a picture a beautiful, romantic dream of something that never was, never will be - in a light better than any light that ever shone - in a land no one can define or remember, only desire - and the forms divinely beautiful - and then I wake up, with the waking of Brynhild”. This romanticism did not endear him to all at a time when realism was all the rage. Indeed, Burne-Jones seemed forever embroiled in controversy. An 1870 painting - “Phyllis and Demophoon” - featured his scantily-clad model Maria Zambaco (with whom he conducted a passionate affaire) allegedly in a posture of “female sexual assertiveness”. This was not something to be countenanced by the sexually repressed Victorian establishment, and Burne-Jones was ostracised by the press. His baronetcy was deplored by an Arts & Crafts movement whose idealistic notions of craftsmen and working men led to Socialist leanings. His wife, Georgiana MacDonald - herself an artist - and Morris were amongst the critics of his decision to accept. . Burne-Jones did not confine himself to painting and stained glass. He worked with jewellery, tapestry, ceramic tiles and was a book illustrator with the legendary Kelmscott Press. Morris was a lifelong friend and collaborator. It was Morris’s death in 1896 that perhaps led to a decline in Burne-Jones’s own health and his death from influenza in 1898. A memorial service was held at Westminster Abbey at the prompting of the future King Edward VII. It would be fair to say that Burne-Jones’s art has been deeply unfashionable for most of the twentieth century, hopelessly out of kilter with modern art movements. His nephew, the Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, said this of him in 1933, however: “In my view, what he did for us common people was to open, as never had been opened before, magic casements of a land of faery in which he lived throughout his life ... It is in that inner world we can cherish in peace, beauty which he has left us and in which there is peace at least for ourselves. The few of us who knew him and loved him well, always keep him in our hearts, but his work will go on long after we have passed away. It may give its message in one generation to a few or in other to many more, but there it will be for ever for those who seek in their generation, for beauty and for those who can recognise and reverence a great man, and a great artist.” Inevitably, though, he has been “rehabilitated” in recent years and his importance in the development of art is now recognised and has been marked by retrospective exhibitions. His stained glass is perhaps his most accessible work. With the work of the more prolific Charles Kempe, it stands out from the general dross of anonymous Victorian industrial stained glass, the garish colours of which too often prompt unwarranted admiration. Burne-Jones and Morris were perhaps the first to raise church glass to the status of recognised art form. “Romantic” he might have been, but in Burne-Jones’s figures you see recognisably (unbearded!) human faces in recognisably human postures. You might feel as I do, however, that somehow Burne-Jones perhaps unconsciously portrayed Bible stories as just another type of fairy story! The twentieth century heir to Burne-Jones’s position was perhaps John Piper, also primarily an artist, who is best known for the great wall of stained glass at Coventry Cathedral. See also examples on this website at Iffley and Jarrow. Personally, I admire much of the modern glass of the last thirty years or so. For more Burne-Jones glass, see Ribbesford, Brockhampton and Roker. Brampton in Cumbria will follow soon. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||