|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Mary Webb’s research was focused on only two or three decorative themes in English church architecture. Of these her work on the use of Neo-Platonist geometric symbolism - with the Hampstead Norreys font as the nonpareil - was the one that really caught my imagination. I would like to be able to expound to you on the ideas of neo-Platonism - or on any other form of Platonism for that matter - but I can’t. having read around the subject I have concluded that I am in possession of the “wrong kind of brain”. It is abstruse and really you need a compelling reason to try to understand it, something I lack. Reading around it does, however, confirm the influence neo-Platonism had on the minds of the first millennium Christian thinkers. That included the great polemicist and arguably lunatic, Augustine of Hippo. Believing that God created all did not mean that they did not try to understand the world that He had created. Far from it. They entangled themselves in a ever more complex webs of abstract thought. In truth, we should not be too surprised at this. These men - they were always men - demonstrated an ability to tie themselves up in theological knots in ways perhaps unparalleled in human history. That was when they had a Bible to argue about. As I am fond of saying, they danced on the heads of pins only because mankind had not yet discovered the atom. What then were they to make of mere philosophical concepts? Well, of course, they thought they were right and everyone else was wrong. As they always had. When we look at the nexus of Mary Webb’s research we are looking at sculpture of the Norman period. Although her library research was Europe-wide, her sculptural discoveries were nearly all in England. In fact, we are probably looking at sculpture dating between 1120 and 1170 when figurative carving in England was at its zenith. If this imagery is traceable back to the schools of Greek philosophy, however, we would expect examples to have survived from the centuries before the Norman Conquest and in countries beyond these shores. Mary identified one or two images from outside England at Rouen and in Rome. She did not show photographs possibly because her research pre-dated the Internet. Moreover, most of her documentary proof even though it was drawn from outside England was also of the twelfth century. The notable exception was a page from “de Natura Reum” of Isidora of Seville which very clearly explained the significance of the “circle with arcs” motif that is so much more common than the other geometric designs. I have only one personal photograph of these designs outside England. Frustratingly there are few that are familiar with Mary Webb;s work and, to be frank, there are elements of “Not Invented Here” amongst those that are. Unsurprisingly then, given the wealth of more photogenic material in first millennium church sculpture, it is almost impossible to find examples on the Internet either. However, I had two breakthroughs recently. Firstly I was sent a picture of the apse at Moirax Abbey near Agen in south-west France. |

|

||

|

Well, I don’t think anything could be much clearer than that, do you? In this picture there are seven “circles with arcs” designs with slight variations between each. The church is for a Cluniac monastery and it dates to around 1049 - before the Conquest certainly and outside England - but not enough to satisfy a yearning for examples from earlier, pre-Romanesque times. |

||

|

I then got another stroke of luck. I found a website called “The Green Man of Cercles”, Cercles being a place in France where the site owner - Julianna Lees - lived. There are several articles on this site well worth a read (I will be referring out to a study on the “Three Hares” or “Tinner’s Rabbits” that is particularly compelling). One of those articles was about the origins of “interlace” sculpture. On that site were several pictures of the circles interlaced with arcs - from Europe and in much earlier than the Norman period. What’s more - glory be - Julianna Lees mentions Mary Webb. I have tried without to contact her to get her permission to reuse some of her pictures. I hope if she sees this page she won’t be cross with me. Others I have sourced via Google. |

|

|

This sarcophagus is in Narbonne in south east France and dates from the sixth century! The geometric design is central, not peripheral. It is large, bold, unadorned and unmistakable. To the left of it, I have to assume, is a very Christian Adam & Eve motif. As with the grave slab from St Bee’s Abbey in Cumbria, this design must have been Christian, not pagan, not Platonist (despite that having been its origins) and most certainly not “decorative”. Moreover, I don’t know whose sarcophagus this was but it was very clearly of someone - probably a churchman - of high status. |

|

|

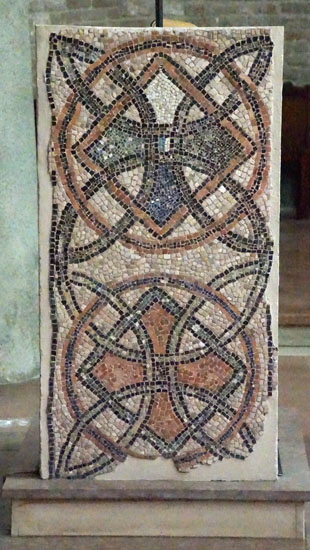

Julianna Lees also did a study on stone chancel screens in France. This one if at St Guilhem-le-Desert and is ninth century. St Guilhem is in the Herault region of south-east France. |

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

Left: Fragments of another chancel screen at St Pierre, Vienne (south of Lyon) and now housed in the cloister of St Andre-le-Bas. The design on the left is quite interesting and not obviously a circle with arcs design because the loops have been collapsed within the circles so that they form a diagonal cross. it is, however, almost exactly the same design as appears on the font at Stoke Canon in Devon. Note on the right there is an example of the “Solomon’s Knot” device. Right Above: This is a square interlaced with arcs appearing in a graffito at the church of Rou in Anjou, In fact, it is a representation of a square on a square (you need to look at the design created by the arcs in the centre). This was identified by Mary Webb as representing the “perfection of numbers”, You can see the identical design on the font at Sculthorpe, Norfolk and on the carved lintel displayed outside St Bees Church, Cumbria. Right Lower: A circle interlaced with six arcs. a design not explained by Mary Webb but seen by her on fragments from Reading Abbey, |

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

Left: A contribution of my own this time. This is the font is at Inisitogue in Ireland. It has a curious history and none of the literature I have seen has shown any awareness of the significance of the carvings. Apparently (only in Ireland?) this font was carved only on two sides. Then someone decided to carve exactly the same designs on the two blank sides. This picture (the only one I could find) seems to be of the “new” sides but we need not worry as apparently they are identical to the “old” ones! Right: Re-used chancel screen fragment at Fontaine de Vaucluse near Avignon. |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

This is perhaps the jewel in the crown of these pictures (which I credit with thanks to Chris Juden who had posted it on Flickr). It is the font of Mauriac in the Auvergne. See the circle with arcs below the central design. It is twelfth century so it does not fulfill my aim of proving the longevity of the neo-Platonist designs but it adds to the conviction that there was something deeply meaningful going on here. |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

From a sarcophagus, Arles, Provence. |

||||||||||||

|

I think there is enough material here (not to mention that in England) to show that the geometric designs are not only meaningful but that they are also both widespread and had considerable longevity. This was very satisfying but I still had the nagging worry that if this iconography was an ancient as Mary Webb claimed, then we should be able to trace examples even earlier than the sixth century date of the Narbonne sarcophagus But how do you search the worldwide web for designs that have no commonly understood name? In 2022, I went on a tour of Ravenna and Venice. This tour was specifically targeted at visiting sites associated with the Byzantine or Eastern Roman Empire. Ravenna was the capital of the Roman Empire for many years, then lying in marshy wetlands more defensible than the city of Rome. And for part of the fifth and sixth centuries the rulers there were the “Barbarian” Ostrogoths, de facto rulers of both the Western Roman Empire and of the Italian peninsular (Italy not, of course, becoming a nation until 1848). Like most of the tribes given this epithet by Roman historians, the Goths were anything but Barbarians. Under the reign of Theodoric the Great, in particular, the peninsular experienced stable and well-ordered rule with many Italian Romans being part of Theodoric’s “Civil Service”. Theodoric and the Goths were Christians and the joy of visiting Ravenna is to see the wonderful Christian churches and mausoleums that were erected during their rule. It is a matter of record that they were considerably more religiously tolerant than other European rulers and were themselves adherents of Arian Christianity. This meant that they believed that God the Father must be ipso facto senior to God the Son. This simple logic put Arians at odds with Orthodox Christianity that had decided, using tortured logic and completely without direct scriptural support that “God the Father, God the Son and “God the Holy Ghost” were three entities with one substance. No, I don’t get it either, but with tedious predictability Arianism was regarded as heresy. In Gothic Ravenna, however, Arianism and Orthodoxy were allowed to flourish side by side. Early in the sixth century, however, the Eastern Empire succeeded in reconquering Italia. Thus the city has a beguiling palette of churches and cathedrals, reflecting Gothic and Roman tastes and beliefs. Surely, I thought, amongst all of the many sites I would visit I would surely find at least one example of Mary Webb’s geometric designs? On the very last day of our very last day in Ravenna, when I had resigned myself to drawing a total blank, I found the examples below, pieces of surviving fifth century floor mosaics in the church of St Giavanni Evangelista. It is an Orthodox church, not an Arian one and was built by Galla Placidia (d. AD 450) an Italian Roman Empress, wife of Emperor Constantius and before that to Ataulf, King of the Visigoths. So here we have an example of the circle interlaced by arcs dating from the first half of the fifth century. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

These two are the only remaining floor mosaics in the church after they were stripped out in 1747. Interestingly, not to mention bizarrely, the design is designated a “hooked cross” on Wikipedia. That is a name usually used for those who no longer like using the term “swastika” and this design is palpably not that. It is a pretty safe bet that in France we are seeing here only the proverbial tip of the iceberg as identified by Julianna Lees. Unfortunately until or unless Mary Webb’s work is more widely recognised (it needs more than just myself) people are not going to photograph these seemingly random designs and post them on the web for us all to see. It must surely be the case that the iconography was used other than in England, France, Italy and Ireland. If you are reading this article and visiting churches in Europe please look out for them. It is impossible to overlook the fact that the circle interlaced with arcs design is the overwhelmingly dominant one of those Mary Webb described from the Hampton Norreys font. At Moirax that design gets a whole frieze to itself. We can say the same for some of the chancel screens shown above. We needn’t be worried about this: it is unsurprising if one of the themes was seized upon as having particular resonance. “Cosmic Harmony”: it’s a nice concept isn’t it? Nevertheless, there is a further picture from Moirax Abbey below. On this apse you can see a number of “other” designs. Some, I think, are probably variations on the symbolism spotted by Mary Webb but I can’t help feeling that the masons were also doing a bit of freelance development of the neo-Platonic iconography. |

|

|||||||

|

And finally...I thought that Moirax Abbey might have the best display of this geometric work in Europe but that accolade might belong to the exotic location of.....St Peter’s Northampton. Blimey! |

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

St Peter’s Northampton. The sculpture here is from the Norman period and was relocated to its present position on the west side of the tower. |

|||||||