|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

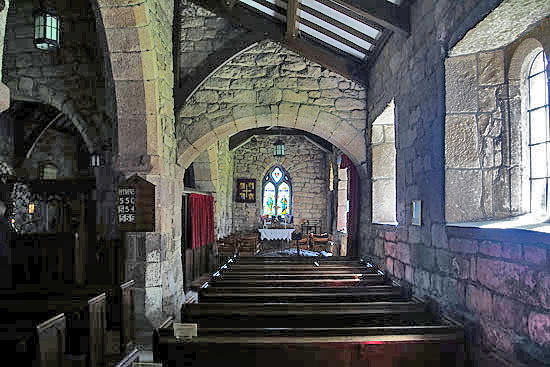

mid fifteenth century south aisle has an Anglo-Saxon west window and an a Anglo-Saxon doorway, both of which have been moved from their original locations. The east wall of the nave is original Anglo-Saxon but its chancel arch is Norman with an unusual and very simple ropework moulding on its capitals. This suggests that the first chancel was itself Norman and that the Anglo-Saxon church was a single cell. We cannot altogether rule out a shallow Anglo-Saxon nave in the style of Escomb in County Durham, however. The Norman chancel itself was obliterated by its replacement in 1340-50. A north aisle was added as late as 1864. It was then that Anglo-Saxon north door was discovered within the north wall and was reconstructed in the south west churchyard. Despite all of this change, the church emanates the unmistakable air of antiquity. It is low in profile - although the height of the nave seems to be original Anglo-Saxon - and sparsely windowed. This atmosphere is enhanced by the Viking hogback tomb that is preserved within the south east of the church. hogbacks are unique to the north of England and very rare. The shape is believed to represent the roof profile of a typical Viking hall.. Like all hogbacks it is covered in mysterious decoration that is largely of the Norse gods. Some experts believe some of the imagery to be Christian, however, so that the stone represents the ambiguity of the Vikings as they clung onto their old gods whilst embracing the “new” one. This can be best seen, perhaps, in the Isle of Man and on the preserved cross at Dearham in Cumbria - amongst many others. The Heysham hogback is popularly regarded as the finest there is. Finally, the churchyard itself yields up a number of antiquities. The base of a ninth century cross shaft near the churchyard entrance is the best of these. The east and west faces have interesting Christian symbolism. |

|

|

||

|

Left: Looking towards the east. The chancel arch is simple and Norman although the wall within which it is set was the east wall of the Anglo-Saxon nave. There was to be a wedding an hour after we visited by the way; hence the floral decoration. Right: The fourteenth century nave. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The west end of the church. The central section is the west end of the original Anglo-Saxon nave. You can see the original west door that has been filled in. If you mentally erase the aisles form this scene you will understand that the original church had the typical large height:width ratio. The bell cote is early eighteenth century. Right: Looking east along the south aisle. The hogback is just visible in the background. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking west along the south aisle. Centre: The filled-in original Anglo-Saxon west doorway. Note the size of the stones creating what is called a “pseudo-arch”. Right: Looking east along the south aisle with the hogback in the foreground |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Left: The south door to the chancel is Anglo-Saxon but has been moved here from elsewhere in the church. Centre: The blocked west door. Looking at both of these doorways the use of massive arch stones is very conspicuous. Right: looking again towards the east end and the east wall of the Anglo-Saxon church. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The unusual ropework design see on the capitals of the chancel arch. Right: Looking east along the north aisle. The aisle is nineteenth so the round arch is not Norman, of course. Note the low windows that still manage to have full Gothic-style windows! |

|

|

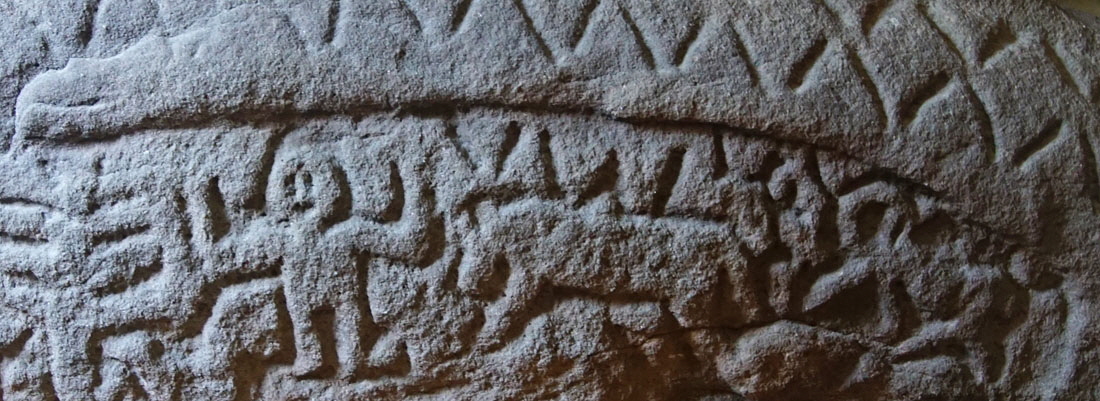

The hogback tombstone. This is believed to recount the story of Sigurd. |

|

|

This side of the hogback is about Sigmund, the dragonslayer and father of Sigurd. More about this in the footnote below. |

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

Left: Close-up of “Sigmund. As you can see, the carvings are robust rather than refined! Right: Most hogbacks always have “end beasts” at each end. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

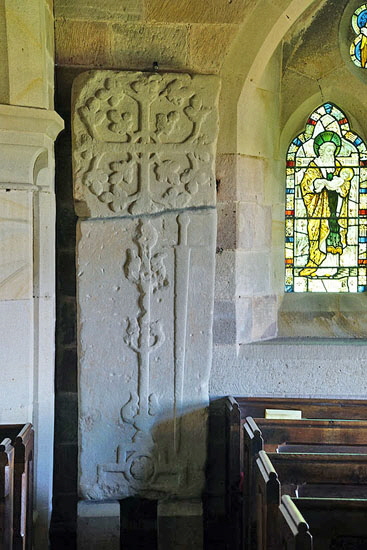

Left: The ridge of the hogback. Centre: Floriated cross slabs such as this one are hardly unusual in the north country but this thirteenth century specimen housed in the west end of the north aisle is particularly fine. Note the splendid broadsword. Right: There is a very interesting ninth century cross base in the churchyard. This Church Guide suggests this side is likely to represent Mary with Jesus in her arms or Christ holding a book. I have studied WG Collingwood’s sketches in his “Northumbrian Crosses of the Pre-Norman Age” and assuming he sketched it accurately. Christ holding a book looks the more likely. The book was written in 1927, so there have been ninety two more years of weathering. |

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

Left: This s the most intriguing face of the cross shaft. Collingwood called it “The Dolls House”! the Church Guide suggests that the central figure is Lazarus. Centre and Right: The other two sides are decorated with scroll-work. |

|

|

|

Left: Down the bottom of one side, however, is an interesting bit of interlace design. It has been cut-off sadly so we can’t get the full picture. Collingwood (book reprint still available from Lanerch Press) “fills in” the missing detail but in this case I am not altogether convinced that it is accurate. Right: Re-set innocuously in a corner of the churchyard is an Anglo-Saxon doorway completely in the style of the other doorways here. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

Left: The church from the north east. Note the squat proportions of the north aisle with windows reaching almost to the eaves. Right: The view across Morecambe Bay. |

|

Footnote - the Heysham Hogback - and Hogbacks in General |

|||||||||

|

Hogbacks are an enigma. Little is really known about them. They are obviously Anglo-Scandinavian (“Viking” if you prefer) and they are found exclusively in the north of the Great Britain. Their geographical pattern suggests Norwegian (Norse) provenance and not Danish. Our use of “Viking” to describe all first millennium things Scandinavian is flabby, if understandable bit of nomenclature that ignores transnational cultural differences. They probably all date from the early tenth century, even possibly within a short window of AD 920-950. They are found nowhere else in the world apart from a single example in Ireland. They are NOT found in Scandinavia! Remarkably, in my view, nor are they found in the Isle of Man where so many Celto-scandinavian cross slabs are found. What actually are they? Remarkably, even that is not clear. From their dimensions (generally about two metres in length) the assumption is always that they were grave covers. Yet none has been associated with a grave. Nevertheless, grave cover is the most likely explanation and association with funerary practice is nearly certain. But are they Christian? They are associated with churchyards so our working assumption is always “yes”. The problem, however, is that there is no Christian iconography on any hogbacks. The Heysham hogback, for example, has Sigmund and Sigurd of which more anon. There have been feeble attempts to read Christianity into the admittedly obscure decoration but they have convinced nobody. Is it then the case that these two Scandinavian legends can be seen as paralleling the Christian story? I daresay we could contrive such a story but, again, it is nothing more than speculation. There are no hogbacks within the Isle of Man but no end of Christian iconography sitting unashamedly next to part of the Scandinavian pantheon. The Norse did not, it seems, need to deal in enigma. If they believed in both Christ and Odin (and everything, including commonsense points to this often being the case) they saw no reason to be coy about it. Thor Ewing’s splendid paper “Understanding the Heysham Hogback” points out that when Wessex absorbed the northern counties Bishop Wulfstan (Bishop of Worcester from AD 1008) saw fit to create laws to deal with paganism. The notion that Christianity had obliterated the Scandinavian pantheon is wide of the mark. Thor Ewing says with splendid accuracy: “...to a pagan, Christianity means the adoption of the Christian God; to a Christian it means the renunciation of the pagan gods”. There has been no end of debate about what the Heysham hogback decoration means and Thor Ewing’s paper can take you through all of that. Our problem is that insignificant motifs that mean nothing to us might have been instantly recognisable to the audience of the time; and that audience might have been a limited one. If a hogback was carved for a great warrior or a nobleman that would be his intended audience - not the tillers of the fields. So who were Sigmund and Sigurd? Well. for a start they were respectively father and son so the idea of both appearing on the same stone has a feel of authenticity. Sigurd - the dragonslayer - is better know to us as the “Siegfried” of Wagner’s Ring Cycle, Sigmund’s story is told in the Volsung Saga of Norse mythology. It’s complicated, of course. Sigmund is one of ten sons of Volsung. He has a sister, Signy, who marries King Siggeir of Gautland. Sigmund, in an echo of the King Arthur story, is the one man who is able to release a sword buried by Odin in a great tree. Siggeir covets the sword but his attempts to buy it are rebuffed. Three months later Siggeir invited the Volsung clan to his home. The Gauts kill Volsung and capture the sons. Siggeir’s mother is a shape-shifter and every night in the guise of a wolf she kills and eats one of the sons. in a final act of desperation Signy overs Sigmund in honey. The she-wolf licks the honey and makes the mistake of putting her tongue in Sigmund’s mouth whereupon he bites it off and kills her. There’s a lot more but you can find that all out for yourselves if you’ve the inclination! |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

The top section of the west panel (above) has a small vignette of a man bound (we see him from above) and with a hound or wolf approaching him from his left. Thor Ewing believes this is Sigmund waiting for the wolf. The rest of the panel has four more men and five wolves that Ewing believes some of Sigmund’s brothers. Again, this is not the place to explore all of Ewing’s theory but you can find it at https://www.hslc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/152-2-Ewing.pdf. |

|||||||||

|

Sigurd was the son of Sigmund and slayer of the dragon Fafnir. By drinking Fafnir's blood he learned the speech of birds. Sigurd is often represented sucking his pricked thumb or with a fire with a spit. These attributes aren’t here at Heysham. That doesn’t necessarily disqualify him as the subject of the eastern side of Heysham’s hogback but there absolutely needs to be a dragon! Imagine St George without a dragon and you will get the idea. The key to this piece, according to Ewing, is that there is a dragon but that it is hard to spot. More about Sigurd in Halton (below). |

|||||||||

|

|

If you look at the picture above what seems to be just a nondescript decorative band has a head (extreme left). Below him is a male figure. This is Sigurd. In his right hand “visible in a good light” is a sword. It is easy to be sceptical but you have to remember that the sculpture would have originally been painted. To his right there are two horses, once of which would be Sigurd's horse, Grani. You don’t have too believe any of this, of course. The Church Guide does and I have to say that it seems much more plausible to me than far-fetched references to Christianity. So pagan then? Not necessarily. These sagas were folk tales. Yes, they included the Scandinavian gods but that does not make them part of pagan religion. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

in Anglo-Saxon architecture. The head of the doorway, however, is of three separate curved linter stones laid in parallel. There is no impost block: the lintel stones lie directly upon the jamb stones below. It is a masterpiece of simplicity. There are rebates on the inner side of the doorway that were for the hanging of the door and this helps to give the chapel (and St Peter’s Church) an early date, possibly as early as the eighth century but more likely of the ninth.. The other remarkable survival here is a group of six graves carved out of the “living” rock. As with everything else here dating is a matter for debate, varying as widely as tenth and thirteenth centuries. Nigel and Mary Kerr in their really useful “Guide to Anglo-Saxon Sites”, however, opt for the earlier date. At the heads of the graves there are sockets that surely were designed to accommodate stone crosses in the Anglo-Saxons style. Thirteenth century? I really don’t think so. It is also believed that the graves did not accommodate complete bodies at all, but were ossuaries for the bones of the individuals. This perhaps points to the possibility that all of the individuals were sanctified or venerated. By the way, those amongst you who are of that era and inclination (I am the former but not the latter) might recognise the rock graves as having featured on a “Black Sabbath” album cover! There are some excellent information boards on the site. They suggest that the priest would have conducted prayer outside the building. They point to the existence east of the church of the socket hole for a stone preaching cross. This idea has a lot of merit. Such small-scale buildings to house the priest were commonplace in the Isle of Man (where they were called “keeils”) and in Ireland. It is believed that the building was expanded in the tenth century when the cult of St Patrick was growing. Indeed, the display boards even float the idea that the bones of the saint might be interred here. Eighty four skeletons were found around the site in three separate cemeteries dated to the tenth and eleventh centuries. Eight bodies were found inside the chapel space. All in all, the Heysham site seems to have had considerable significance in Anglo-Saxon Christianity. |

|

|||||

|

|

||||

|

Left: The surviving doorway from the outside looking in. Centre: The doorway showing the massive through-stones and the strange arrangement of three concentric lintel stones to form the arch. Note the rebated jamb stones on the inside. Right: Ancient grave markers outside the chapel. |

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

Left: The chapel from the north west. Right: Looking towards the almost intact original east wall. |

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

Two view of the rock-hewn graves west of the church. It is difficult to believe that this amount of trouble was taken for anything other than men thought worth of veneration. Note in articular the socket holes at the heads. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

Two pictures shamelessly copied from the information boards! Left: An imagination of the first manifestation of the chapel. It shows no south door, implying that was added later, although I think this is total speculation. The priest is preaching outside and there is a preaching cross to the east end of the church. The rock graves are showing behind the priest and, again, we have no way of knowing if they were this old. Right: An imagining of the expanded church tenth century church now has the south door and the chapel has expanded to the east. The priest is now welcoming people at the door. The preaching cross is gone but the number of rock graves stays stubbornly at four. It is easy to pick holes in these pictures but as a away of imagining the first millennium scene here I think they are very useful. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Fafnir who was guarding a hoard of treasure. And if you are thinking that Tolkien must have read this saga you would be totally correct! Regin and his brother had killed their own father to obtain the treasure. Regin’s brother was none other than Fafnir who had transformed himself into a dragon to dispossess Regin. Regin was disguised as a smith and he offered to re-forge the sword that had belonged to Sigurd’s father, Sigmund who had received it from Odin. No ordinary sword, then. Armed with the formidable weapon Sigurd duly slew Fafnir. Regin, obviously a man of much charm, then asked Sigurd to roast the unfortunate Fafnir’s heart so he could eat it. Sigurd accidentally burnt his thumb during the cooking process (no oven gloves in those days, you see). Sigurd did what anyone in his position would have done and promptly stuck his sore thumb in his gob. There was a speck of Fafnir’s blood on that sore thumb. When it made contact with Sigurd’s tongue he was suddenly able to understand the songs of birds. In the tree above his head were two nuthatches who warned him of Regin’s treacherous intentions. Sigurd did what any self-respecting hero would have done and cut off Regin’s head (hurrah). Sigurd loaded the treasure onto his horse, Granir, and rode off into the sunset. Unfortunately for our somewhat flawed hero the treasure included a gold ring that had belonged to the dwarf Andvan and was now accursed. Sigurd thenceforth lived a life of misfortune before shortly dying. He didn’t even get a share of Tolkien’s money. Phew! Now you will notice that these events are a bit obscure on the Heysham hogback, but not here at Halton. One panel has Regin re-forging the sword surrounded by the tools of the smith’s trade. Other key events portrayed are a headless Regin, Sigurd sucking his thumb while he roasts Fafnir’s heart, the bird’s whispering in Sigurd’s ear and so on. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Centre: Two views of the churchyard cross. It has been reconstructed with many of the decorative parts lost. At this point it is important to observe that this is a cross. So when we see the Sigurd saga here we know we really do have an Anglo-Scandinavian composition. The question we must pose is why is it here? Sigurd was not a Norse god and Odin appears only peripherally. Its appearance here does not imply religious ambiguity. Was the saga seen as having Christian lessons? Well maybe. Avarice is the main feature of the saga. Regin and Fafnir come to a bad end and Sigurd fares little better. It seems just a bit far-fetched though to think that so much of the saga was shown here in such detail just to prove that point. I think perhaps the new settlers didn’t let God get in the way of a good story. Nigel and Mary Kerr said “The Sigurd Cross is an important survival from the twilight years when Christianity and paganism battled in the minds of men”. Right: This is my favourite panel. This is Regin re-forging the sword. You can see him seated on the left, hammer in hand in front of a table. Top left is a sword or dagger, Next to it is a pair of pincers. To its right is an odd figure of a human with a piece of interlace for his head. I don’t understand that. On the table is an indistinct shape that is presumably the damaged sword. Below the table are what look two pairs of bellows. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: In the lower panel Sigurd is roasting Fafnir's heart. W.G.Collingwood’s sketch suggests Sigurd’s scorched thumb is raised which would make eminent sense. In the panel above two nuthatches tell Sigurd of Regin’s treachery. Second Left: The most obvious motif here is Sigurd’s horse, Granir. Above him is Fafnir who is represented by two dragons intertwined. The panels below are indistinct although the bottom one seems to be interlace work. Second Right: Just to remind ourselves that is is a cross shaft The upper panel here shows a figure - possibly an angel - with two smaller figures possibly grasping his legs. In the lower panel two more figures hold onto a tall cross. Right: The The fourth side of the cross base is Scandinavian style decorative work. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Halton Cross is actually a confection. In 1635 the vicar decided to cut off the top part of the cross and used the base with its Sigurd story as a sundial. Nobody knows what happened to the rest. In 1891 it was reconstructed using some other pieces of old carved stone found around the churchyard. This stonework predates the Viking era so all we do know about it is that it was not part of the cross built upon the base with the Sigurd story. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The upper part of the shaft has an evangelist carved on each of the four sides. It is difficult to put any interpretation on the fragmentary carvings below. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The cross head is obviously modern with the exception of the top arm which is of old Anglo design and which was found inside the church. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||