|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Romanesque cruciform church but, sadly, that is not the case. In around AD1300 the apses were removed and the chancel was rebuilt and extended. A chapel was added to the east of the north transept but this has been demolished. The chancel windows we see today were, apart from a “low side window” to the south, replaced in around 1840. The glass in the east window was shown at the Great Exhibition of 1851. Despite these alterations, around 80% of St Nicolas has its origins in the Anglo-Saxon and Norman periods. It is the Norman crossing that dominates this church and, it must be said, it is probably a complete pain in the neck for priest and congregation, creating a considerable discontinuity between nave and chancel! Each of the four arches is original and their orders of decoration are particularly distinctive including, amongst other things, courses of rosettes and limpet shells, some of which pay tribute to Shoreham’s former maritime importance. High above the crossing are the small Norman tower windows. The tower is a rare beauty, complete with a stair turret on the north west side. Each side has a group of three window openings, two of each being “blind”. Above this is a unique course of round openings, two on each side. The tower is intact and priceless. Entry to the church is through a Norman west doorway to the south transept. Passing through this door and into the crossing is one of the most remarkable entries to any of the English churches I have visited. The nave has Anglo-Saxon fabric. The north wall has both a blocked Anglo-Saxon doorway and a Norman one, which must be pretty unique! This church has, remarkably, a Norman tie-bar made of timber and complete with billet moulding across the east end of the nave. It also has an original wooden tie-beam across the chancel, still with its mediaeval paint. Sadly, the area around the north transept is a total mess. This tiny church apparently had need of both a choir vestry and a vicar’s vestry. Just to cap it all (literally) the bell stair has acquired - of all things - a chimney pot! It’s grim, frankly. This is a much-loved church, however, and kept with pride by its congregation. It’s a gem. If you visit this part of West Sussex this little slice of history should be on your “must see” list. |

|

|

||||||

|

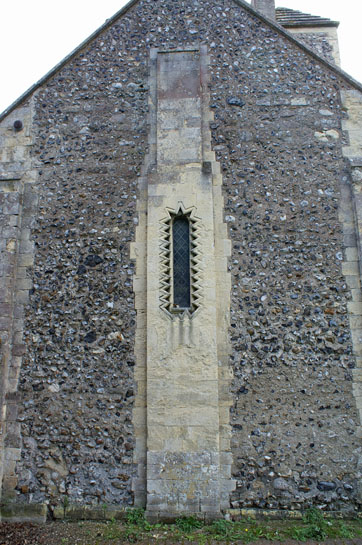

Two views of the tower. Note that this church is constructed from flints rather than from dressed stone. Note the modest proportions of the corner stones. |

|||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Left: The chancel dates from around 1300, although the windows are more modern. Right: The nave betrays its Anglo-Saxon origins. On the north side (right) we can see that the western tower was not as wide as the nave. Yet on the south side it appears that the widths were the same, so some kind of modification to the wall line is likely to have occurred. Also on the north side we can see the blocked Norman north door. The wall-mounted monuments - as at so many churches - are an unfortunate eyesore and we have a rather peculiarly-sited set of organ pipes here too! |

|

|

|

Capturing the atmosphere of the Norman crossing is impossible with mere photographs. What is more, low light means compulsory flash photos and the light bounces all over the shop in such a confined space. So I apologise for underselling its glories! Left: Looking into the south transept. Right: The eastern arch is to the left and the southern one to the right. |

|

|

||

|

Left: The northern and eastern arches. Right: A direct view of the western arch looking into the crossing. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||

|

Left: This arch has an unusual outer course of daisy chain decoration. The chevron moulding has some extra adornment inside each “zig”. The three courses of decoration provide a unique composition. Right: This crude and menacing “cat mask” is above the keystone of the western arch. |

|

|

|

Left: One of the arches has this outer course of fleurons. Right: What I referred to above as “daisy chain” motif. In fact, the “flowers” are circles with eight sectors, all surrounded by a zig zag design. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

|

||||

|

Three of the many primitive carvings scattered around the chancel crossing. Left: What the Church Guides declares to be an “elf form” on the west face of the western arch. The carver was obviously not familiar with the “Lord of the Rings” films...Centre: The northern arch has faces carved at each end and the speculation is that they represent King Stephen and his wife, Matilda of Boulogne (not to be confused with Stephen’s cousin Empress Matilda - or “Maud” - who was the daughter of Henry I and with whom Stephen fought a long civil war in a period known as the “Great Anarchy”). An alternative view is that they are Henry I and his second wife, Adeliza. If they were recognisably Stephen and Matilda then this was a dangerous representation given that the south of the country was frequently at the epicentre of the troubles! I guess neither lady would have felt flattered by this pop-eyed representation of her charms! Right: An unidentifiable face. |

|

|

|

Left: You can decide for yourself what this capital on the southern arch represents. Note, however, that what looks at first glance like a contemplative hand beneath the chin is in fact a rather cheerful-looking beastie! Right: The arch of the the south transept door that is now the church’s entrance. Note the delicacy of the outer course of decoration. |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The south transept doorway. Centre and Right: The doorway capitals. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The eastern face of the crossing. The Norman tower is short by the standards of the mediaeval towers of subsequent centuries but, nevertheless, the uninterrupted wall from crossing arch to tower window gives it a lofty appearance from within. Right Above: The mediaeval paint on the wooden chancel tie-beam. Right Below: Detail from the Victorian chancel ceiling. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Right: The tails of the mediaeval tie-beam. There are geometric (and unpainted) carved designs visible - with the aid of telephoto lens! - at each end. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The north side is a bit of a mess. There’s nothing wrong with the add-ons in themselves but putting it all together makes a bit of a grim scene. Churches have to fulfill their primary function as well as being there for antiquarians and photographers so it would be wrong to be judgmental, especially as the people of the church care so obviously care so much about the building they hold in trust for us all. So, I’ll content myself with a sigh...! Right: The north east side shows the masonry course that marks the extent of the original Anglo-Saxon tower, while to the right we can see a filled-in Saxon doorway. To the left is another round-headed doorway, presumably Norman? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This ugly buttress mars the west end. A faux Norman window has been set into it at some point in time. The zig zag decoration was done to very high standards - the Normans would have been jealous - but it just looks wrong. Curiously, a good half of this window has blocked on the inside in order to accommodate the organ pipes! Centre: The south east corner of the tower. Hidden by the gravestone is a “low-side window”. See the footnote below for more about these. Note the quite conspicuous change in masonry on the transept. This dates from the removal of the apse that was originally on the transept’s east face. The masonry nearest to the chancel is part of the original Norman building. The rest is a mediaeval wall replacing the apse. Right: The delightful approach to the church’s main entrance on the west side of the south transept. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Above one of the capitals is this distinctly modern - and rather charming - carving of a mouse. Not for the first time I have to reflect that the humble mouse is almost an icon in churches with little carvings often hidden away in woodwork or stonework. Yet, I wonder how many churches don’t have a mousetrap or two somewhere in their buildings? Right: Visible from the church grounds is Lancing Public School. American visitors to this site will need to understand that in England only best private schools are known as “public schools”! Lancing would set the ambitious parent back óG27k pa at the time of writing. The chapel was begun in 1868 and was originally intended to have a western tower. It is quite a pile. With its apsidal chancel, lofty height and multitude of flying buttresses it admirably achieved the original intention of emulating mediaeval French gothic style. Note that this picture was taken with a long telephoto lens: the school is nowhere near as close to Old Shoreham Church as it appears here. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote 1 - “Low-Side Windows” |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I always wonder whether why that hyphen is where it is. Aren’t they “low side-windows”? Anyway, they are actually quite common in English parish churches, usually but by no means always on the south side. Some have evidence of having had shutters so we know that these windows were, in fact, originally unglazed. One or two have seats beneath them. What is really curious, however, is that nobody knows what they were for! Some call them “lepers’ windows”, suggesting that it was through such an opening that a leper might have been permitted to view proceedings within. This is obvious nonsense, however, as most lepers lived within “lazar houses” with their own chapels. Moreover, lepers were not allowed within churchyards. What is more, most such windows are at the wrong height to permit a view of the consecration of the host. Why would they be low side windows? This seems to also preclude another theory that the window allowed some sort of priestly acolyte to ring the sanctus bell at appropriate times during the mass.. G.H.Cook in “The English Mediaeval Parish Church” in 1954 suggested that they were there to provide an updraught that would carry upwards to the ceiling the choking fumes from the myriad candles that would have been burned within. That would explain the lack of glazing. The benches, he suggests, might have been there for the priest to recover his breath! Hmm. Hugh Braun in “Parish Churches - their Architectural Development in England” in 1970 quotes “continental priests” that confidently asserted that such doors were for the purpose of donations, in particular “oil for the lamps”. Don’t be judgmental about the age of these books: these are the seminal works on English parish churches. If both Cook and Braun were reduced to speculation and hearsay then low side windows are a genuine architectural mystery! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote 2 - Finding the Church |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I never thought I would have so much trouble finding a church in an English town! New Shoreham is slap bang in the middle of the main shopping area. Old Shoreham, let me assure you, is not a short walk away from it! Shoreham rather charmingly still calls itself a “village” despite a population of 18,000 people! We had immense difficulty finding it and you will, trust me, need a car or bike to get from the New to the Old Church. Do study a good map before you visit or else find the postcode for your sat-nav. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||