|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

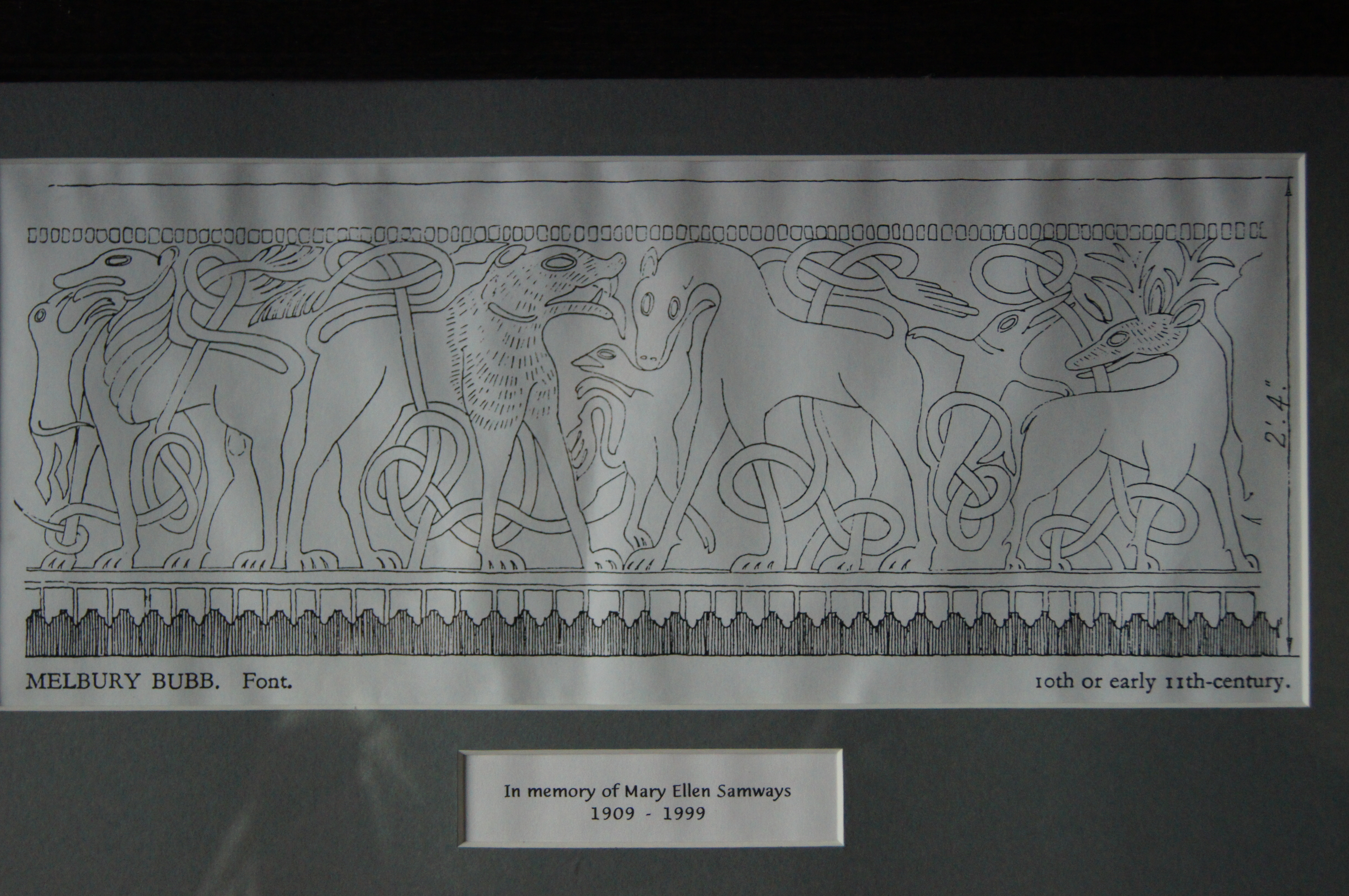

The design around it is a frieze of animals: a stag, a wolf, a lion, and a couple of smaller animals intertwined. One of these appears to be a dolphin. In their book “A Guide to Anglo-Saxon Sites”, Nigel and Mary Kerr suggest “the curving bodies of the beasts owe something to Scandinavian styles, but the relief carving and well-formed bodies are more akin to earlier Northumbrian work”. Well-preserved as this relic is, it must be said that it is not very easy to discern the design. This is, remember, a converted cross shaft so its circumference is not very big and the design, therefore, wrapped tightly around it. And it’s upside down! And there are no electric lights! So, that’s it really. A single treasure church buried in the wilds of a rarely-visited Dorset village. Obscure it might be, but this church is clearly loved by those who care for it and it deserves your visit. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

The west (left) and east (right) ends of the church. There is a blocked west door that presumably was the original entrance before the tower was added in 1474 and which now provided the entrance to the church. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The chancel with its caved reredos and two rather odd faux niches with relief carvings. Right: Looking towards the west end with its blocked west door. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the east. Note the waggon roof, more common in nearby Devon and Cornwall. Right: The south door and porch accessed via the tower. This is a very unsophisticated doorway so I wondered whether it was here before the tower was built to engulf it. The tower’s own south door is similarly crude, however, so probably the south door was after all a 1474 replacement for the now-blocked west door. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The porch roof is adorned by some pretty unpainted bosses. I thought the roses might be Tudor roses but Henry VII didn’t grab the crown until 1485 so that would be impossible - unless the dating of the tower is incorrect. Right: A row of four oil lamps on the south wall. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Font |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

So now to the reason Melbury Bubb is worth going out of your way to see - the font. Its tight circumference and the fact that it is inverted - not to mention the lack of light! - make the complete outline quite hard to discern. So I have taken the liberty of reproducing the diagram on the church wall. There are few descriptions of what these animals are meant to be and I have to say that I can’t reconcile what I see with those descriptions anyway! That on the right might well be a stag as claimed owing to its “antlers but you would have to say that those are the only clues. So how are we to be sure of any of the others? Perhaps the figure second left is supposed to be a lion due to the possibility of its having a mane but even that is pushing things. And what of the rather benign looking creature second right? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Two Views of the Font |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Even having taken what seemed like copious quantities of photographs of the font it is still difficult to piece together a full view if it. To make thinks easier I have inverted the pictures. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

These two pictures equate to the left hand side of the line drawing above. Left: A small creature inserts his beak into the mouth of one of the four larger animals. To the left you can see the head of the stag that it is on the extreme right of the line drawing. Right: The hind quarters and tail of the large animal in the left hand picture and those of the lion (?) to the right of him. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The full body of the left-most figure. Right: At the centre of the design a bird-like figure is shown between the heads of two creatures. The left hand one is the “lion” and the right had one is the peaceable-looking figure second from the right in the line diagram. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

From the right hand side of the line drawing, a dolphin-like figure grasps a tendril or vine stem in his beak. His own tail is tangled below him. To his right is the “stag” figure. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote In Thomas Hardy’s “The Woodlanders”, Melbury Bubb is called “Little Hintock” |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||