|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Another gem from the Church Guide is its explanation for why this church has never had windows in its north side. In some of my webpages you will see references to the north sides of churches being seen by both Church and, in particular, parishioners as being the “Devil’s side”. The Church Guide here traces this to a reference, which I was unaware of, to the Book of Jeremiah which talked of evil coming from the north. This was seen to have been born out by the Viking invasion that in in the Isle of Man also came from the north. Many English parish churches had north doors that were never used for ingress and egress except for evil spirits exorcised by baptism. At Marown the north doorway is also blocked - exorcism no longer being seen as part of the sacrament of baptism - but in being windowless the Manx people here took things a step further! |

|

|||

|

|||

|

Left: The north side presents a totally blank view to the visitor, although there is a blocked north door at the west end. Note also the very unusual blocked doorway in the east end. Right: The interior looking west. There is no sign of the west gallery now except its filled-in door high on the west wall. It must have made the church quite claustrophobic. Note the two fonts in the north west corner and the little vestry on the opposite side. |

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the east end. The two cross slabs are visible to the right of the little altar table. Beyond the yellow curtain is the blocked and highly unusual east doorway. Second Left: The seventh century cross. It is No.50 in the island’s catalogue of its Celtic crosses. Second Left: Cross No.16 has little or no design still visible. Right: The blocked east door from the outside. |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

Left: The north west corner is full of interest. The two fonts are here within the vicar’s pew. Beyond the larger font the now-blocked opening to the outside is clearly visible. Right: The font inset into the wall was originally a holy water stoup. The Church Guide is silent on the provenance of the larger of the two fonts but it looks very old indeed and surely no later than the the twelfth century building. |

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The west gallery doorway. Centre: The very unorthodox west end. The very low entrance is via a tunnel-like porch cut into the west gallery staircases on either side. The west gallery door itself is clearly visible in the middle of the wall. Right: The blocked north doorway that surely belonged to the twelfth century building. |

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Left: The very unusual pulpit/reading desk. It would look equally at home in a Victorian school! To its left are the two crosses. From this angle you can see rather better that the right hand cross slab has a raised area that was presumably decorated. Right: As far as i could see the only lighting here is by candles. If there was any electric supply here I didn’t see it. It is the ageless simplicity of this church that is such a delight. I always feel that if you want to look for God then places like St Runius are where you should go. We know there has been worship here for fourteen hundred years but finery and ostentation have passed this little church by leaving it as a church should be: a place of spirituality, prayer and contemplation. You can keep your monuments to the not-very-great and far-from-good and the grandiose excrescences that they funded. I love all of Britain’s church heritage but whereas I can admire the grandeur of the great town churches it is places like St Runius that lift my soul. Here endeth the lesson.... |

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Left: Just look at the depth of these walls! It makes you scratch your head really. This is the sort of massive masonry you would expect to see on a Norman-era church. Yet nobody seems to think this is the oldest part of the church. You can only surmise that they were forced to build like this simply to properly blend it into the original parts. Those window openings, of course, are far too large to be original so somebody had the monumental task of cutting them into the walls. Having talked of the “Norman era” we need to remind ourselves that there was no Norman invasion of Man and that it had Viking rulers until 1266 when it was ceded to Scotland. So at St Runius (and at Kirk Lonan) you are seeing something very rare: a church that was built under Viking rule at a time when Christianity completely held sway. This is not a church with Viking influence but a product of Viking-Celt Christianity the like of which could not exist on the mainland where the Anglo-Saxons had long ago driven the Celts into Wales, Scotland and Cornwall. Right: The rickety little vestry at the south east corner of the church. |

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

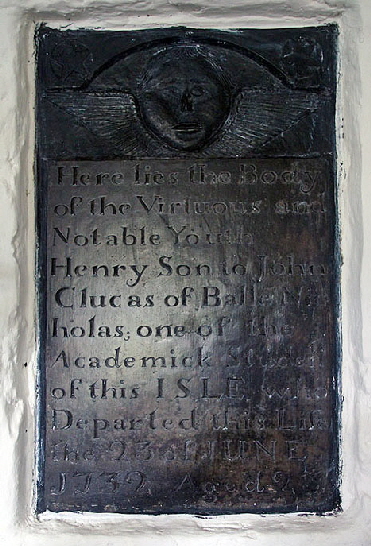

Left: Some church visitors get their kicks from searching out unusual or poignant headstone inscriptions. That’s “not my bag” at all but I liked this little plaque - the only one here - to Henry Clucas (a common surname on the island) from 1732. He died aged only 23 but he was a “virtuous” and “notable youth”, and “academick student of this isle”. I can only hope that Henry found time for a bit of wine, women and song as well before his untimely death. Nobody should die that virtuous! Centre: I can’t for the life of me work out what this recess in the south wall was for. Does anybody out there know? Right: What could be more rustic than this? Moss-grown and fern-strewn steps to the blocked entrance to the now-vanished west gallery. Trailing down is the rather dirty rope for ringing the bells in the little bell cote. At St Runius “unpretentious” is on a different scale to elsewhere. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Our car on the left is parked outside the gate to the churchyard. This picture gives you some idea of how rural this spot is. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

St Patrick’s Chair |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

We haven’t finished with Marown just yet. Less than a mile away, up a not very well signposted track covered in sheep poo and surrounded by sheep is St Patrick’s Chair. It’s not a chair, of course, and it’s unlikely St Patrick was ever there but nevertheless that’s its name. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Braaid |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I’m afraid this is a bit more “mission creep” and I have to confess that Braaid - just two miles or so from Marown - has no direct connection with Christianity. This is a site that contains remains of a neolithic round house and two Viking longhouses. We don’t know precisely how old any of these buildings are but there is more than a chance that the Vikings who lived here were or became Christians and would have been familiar with the keeil at Marown and even with St Patrick’s Chair. I find that thought quite delicious and I hope you do too. Or maybe they still adhered to the old ways and thought that thunder and lightning were the result of Thor and his hammer? Or, a distinct possibility, they thought that the Christian God and Odin were interchangeable - as many of the Celtic-Scandinavian crosses on the island show. Either way, these houses are part of Marown’s Celtic-Viking narrative that is a microcosm of the early history of Man. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The site as you approach it from the footpath. Right: The smaller of the Viking longhouses that was used for cattle. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

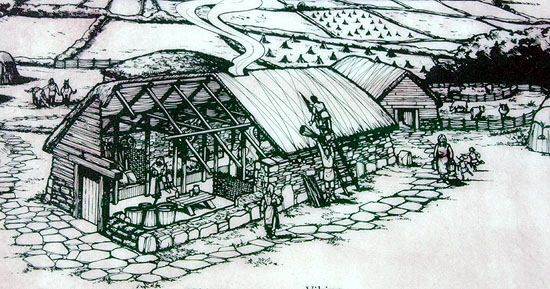

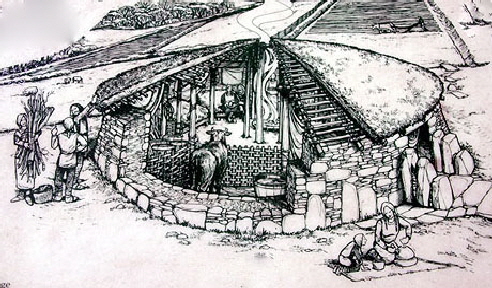

Left Above and Below: The larger of the longhouses with an artist’s impression of its original form. Note the double row of stones to the left of the ruin with the intervening turf area. All of this was one of the outer walls. You can see from the artist’s impression that the end walls were of comparatively thin timber construction. The side walls, therefore, had to shoulder an inordinate proportion of the weight of the roof that wall directed to the sides by its lateral timbers. Right Above and Below: The remains of the Iron Age circular building and an artist’s impression of its use by the Vikings. Note the wattle cattle pen within the building and the large stones forming the entrance. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A closer look at one of the walls of the larger longhouse. Its thickness is quite remarkable. Right: Ferns and Ancient Stones |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The site from behind the smaller of the two longhouses |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||