|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

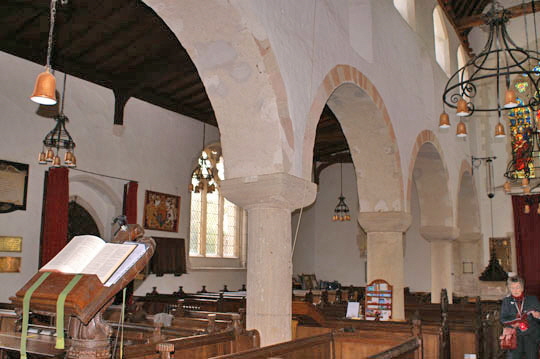

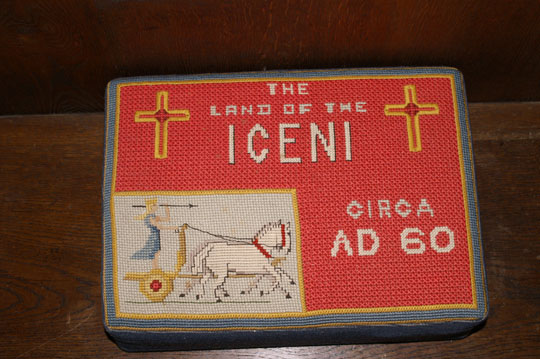

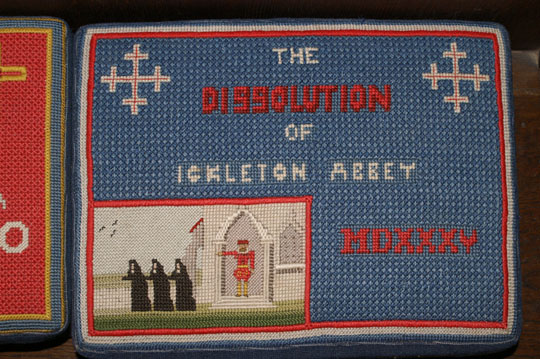

Victorian edifice of 1882. The original Norman tower was also replaced in the fourteenth century although, of course, it was built on its original base. Inside the church the original Norman clerestory has been blocked but the rebates remain, forming what looks rather like a triforium below the current clerestory that dates from fourteenth century. Most of the south wall of the nave and the south transept are fourteenth century. As can be seen in the picture left, the exterior appearance is uninspiring, even messy, belying its impressive interior. The frescoes are quite another matter! Those on the northern part of the nave dates from the twelfth century. With the churches of the celebrated “Lewes School” such as Clayton and Hardham this is one of the most complete Norman cycles in England. The doom painting above the chancel arch is fourteenth century. More than most churches, Ickleton demonstrates how extensively our churches were once painted internally. There were few areas that were not ripe for decoration, extending even into window splays and arcade soffits (undersides). Of course, as with most church frescoes, some colours have survived better than others, but at Ickleton it is not hard to close one’s eyes and imagine it in its original glory. The arcade painting is in four sections: from west to east we see The Last Supper, The Betrayal, The Flagellation (of Christ) and Christ carrying his cross. In the areas between the arches we see the Martyrdom of St Peter; the Martyrdom of St Andrew and what may be the Martyrdom of St Laurence. Only the top part remains of the Doom painting. We can see in this church how mediaeval wall painting transitioned from being representations of Biblical scenes with the purpose of educating the congregation to scaring the hell out of them. The Virgin Mary is portrayed as bear-breasted, leading to speculation that this is Mary Magdalene. That would be surprising if it were true, but the (excellent) church guide book points out that in the fourteenth century bearing the breast was a symbol of supplication, suggesting that in the picture the Virgin was pleading for the souls of sinners. There are some very nice poppy heads on the benches.. Finally, and unusually, I would like to mention the extraordinary collection of kneelers, all embroidered with scenes from Ickleton’s history. The dedication shown by those responsible for this magnificent record is worthy of comparison with that of those who created the frescoes all those centuries ago. |

|

|

||||

|

Left: The south west arcade shows that here too there was painting, although it is visible only around the arches. Note too the last two columns which are of Ketton stone and may be Anglo-Saxon. Right: The church from the north west showing the later clerestory of circular windows. |

|||||

|

|||||

|

A closer view of the north east arcade showing the extent of the painting and also the variation between the decorations on the soffits of the two arches. Note the Norman clerestory sitting below its later replacement. |

|

|

A close up of some of the painting. Top left is the Last Supper with Christ and his Disciples seated at the table. Judas Iscariot is the conspicuous figure taking a fish from the table. This can be interpreted as a theft or alternatively that Christ is represented by the fish and Judas is taking his life. Note that the line of disciples is continued into the splay of the Norman clerestory window. To the right of the window is Betrayal. This scene is not so easy to discern. On the extreme right, Peter is cutting off the ear of the unfortunate Malchus, servant to the High Priest. Judas and Jesus are to the left but it is difficult to see the kiss of betrayal. Lower left is the martyrdom of St Peter by being crucified upside down. Note the complexity and beauty of the painting surrounding the arch itself. |

|

|

Another close up of the Last Supper with Judas (lower left) taking a fish from the table. |

|

|

The Martyrdom of St Andrew. Unfortunately the wretched memorial tablet intrudes but I believe we are seeing the feet and lower torso of Andrew as he is nailed upside down to his saltire cross. Myself, I had always supposed they would have turned the cross upside down after poor old Andrew was secured to it. That would not be such a dramatic image, however. |

|||||

|

|||||

|

Close up of The Betrayal. When I was a lad Peter was always my favourite disciple because he had a sword and cut the man’s ear off. Little snipe that I was, I always hated the passivity of the disciples. |

|||||

|

|

The Doom painting over the chancel arch. Note the somewhat voluptuous bear-breasted Mary to the left of Christ. To his right is either St John the Evangelist or St John the Baptist. Angels float above their heads. Lower right are fragments of those condemned to Hell. Below Christs’s feet a couple of saved people rise from the grave. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

Left: Painting on the soffit of one of the chancel arches. Right: The fourteenth century rood screen survived the Reformation and is extremely fine. |

|

|

|

Left: The Norman West Door. Right: The rood screen looking towards the chancel. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||

|

|||

|

Left: If this were an Eagle then it would be the symbol of St John, completing images of the four evangelists but I am afraid it looks like a dragon to me! Right: A couple of kissing hens here! Aaaahhhh. |

|

The Kneelers |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

This is a very small selection and all are pretty self-explanatory, except perhaps the 1643 kneeler which records the visit of the Puritan “Enforcer”, William Dowsing, who was the scourge of many a church in the East of England. Ickleton lost its steeple crosses and most of its “idolatrous” glass. |

|

|||||

|

|

||||

|

Left: Looking through the arch to the crossing and the chancel beyond. Centre: Ickleton has a font cover that may date from the fourteenth century. Note the elaborate lifting tackle! Right: Unusually, Ickleton has a sanctus bell. Once an important part of the Catholic mass it is a fairly rare survivor in post-Reformation Anglican churches. Sanctus bells derive their name from being rung first during the Sanctus (“Holy, Holy, Holy Lord...”) part of the Mass. |

|

|