|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

originally a rood screen from an other church, moved here and pressed into service as a parclose screen after the Reformation. The Church Guides believes that its original site was probably the collegiate church at Rushford, six miles away, that was suppressed by Henry’s men. The church was supported by the Herling family whose family hubris provides so much of the fun at East Harling and whose family name, indeed, was adopted by the town which was formerly known as “Market Herling”. Beyond the screen are two of the large set-piece monuments and they are full of interest. One is of Sir Robert Herling (d.1435). His tomb provides our first glimpse of two items of the Herling family’s strange heraldic devices: the basket and the unicorn! We will be seeing many more of them. Overshadowing it is the mighty monument to Sir Thomas Lovell (d.1604) and his wife. There are three other Lovell monuments to be seen in the church and another to Sir William Chamberlain and his wife whose monument doubled as an Easter Sepulchre. The Lady Chapel screen may be an “import” - and we shall see that it is of the finest quality - but at the front of the church we see the dado (base parts) of East Harling’s own rood screen. Even these fragments are magnificent and we can only imagine the glory of the screen in its original totality. The spandrels of the south aisle roof continue the theme of extraordinarily fine wood carving, making full use of the Herling family symbolism. Are there finer such carvings in England, I wonder? Musing on the strength of the woodcarving tradition in Norfolk and Suffolk I can only conclude that it was the lack of good freestone in the area led to a channelling of artistic talents into the realms of wood. Then we have misericords; only four of them, it is true. And they are an enigma. I quote the Church Guide: “...carefully reassembled sets of misericord stalls where surviving 15th century woodwork has been incorporated into such skilful 19th century work that it is difficult to distinguish between the two”. What? Which bits are “surviving” is what we would all wish to know, I think! In my view, all of the key bits are clearly original in design, if not in substance. In fact, the armrests are rather more entertaining than the seats that sport designs of heraldic significance. More about them anon. The east window here is another wonder. It is amongst the first rank. It has fifteen scenes, mostly based on the life of the Virgin Mary but including images of Sir William Chamberlain and Sir Robert Wingfield (d.1480) which allows the fifteenth century dating. Its survival is something of a miracle. the glass was removed by the Wingfield family so that it would not become a tempting target for Cromwell’s musketeers and stored in the nearby manor house. It was not re-discovered until Thomas Wright purchased the property in 1736 and decided to restore it to their rightful place. It was removed again for safe keeping during World War II The church’s earliest parts are of around 1300-1340, including the tower (but not the spirelet). The Lady Chapel where the monuments and screen make such an impression was endowed by Sir Robert Herling when he died in 1435. His daughter, Anne, and her two husbands continued to enrich the church after Sir Robert’s death, especially her first husband Sir William Chamberlain who, amongst other things, built the clerestory. Sir Robert Wingfield, Anne’s second squeeze, added the east window despite, as the Church Guide reminds us, the chancel being the responsibility of the rector, not of the parish. Sir Robert’s own image is contained within the glass, and who would begrudge him that? The tower received its spirelet and parapet towards the end of the century. This is a church that has been remarkably well-served by its mediaeval benefactors without quite being turned into their personal building. You won’t be here for the architecture, however, because fine as it is there are many Perpendicular churches of its ilk. You will be here for the kaleidoscopic array of the finest craftsmanship of carpenters and glaziers. This is a must-see church. And it is still beautifully cared for. |

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

Left: The church looking towards the east. The Lady Chapel is to the right. Note the little window in the east wall. They are not very common and are usually quite a lot larger than this one. How much it actually adds to this church, given its huge aisle windows and mighty clerestory, is open to question but it does demonstrate the relentless search for light in late mediaeval churches. Right: The church looking towards the west. Note the symmetry of the tall arcades that date from the first half of the fourteenth century. Note too the sheer height of the nave with its noble clerestory. |

|||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Left: Looking along the south aisle to the Lady Chapel and its screen from - it is said - from the suppressed Rushford Collegiate Church. If you are wondering why collegiate churches were suppressed, it is because in most cases a lot of the clergy were engaged in saying masses for wealthy patrons who thus hoped to shorten their time in Purgatory. The Reformation deplored this notion (I think I do too!) and this sounded the death knell for collegiate churches. Right: The screen from the east end of the church. You do get a good idea here of the width of such screens. It always surprises less-informed church visitors (none of them amongst my readers, of course) that some parts of the liturgy were carried out from a priest balancing precariously atop the screen. Nowadays he would never get the insurance cover and would have to attend Basic and Advanced Rood Screen Safety courses. Of course, it would have originally have had a rood (cross) and the figures of Mary and St John the Evangelist but these too were victims of the Reformation on the not-altogether-ridiculous grounds that such things were akin to worshipping graven images, although I rather suspect that the strictures in the Old Testament (which was a Jewish text, anyway, let us remind ourselves) were aimed more at images of other gods. I seem to remember Moses was particularly hacked off when, having taken the trouble to climb Mount Sinai to receive the Ten Commandments, he found that those naughty Israelites had melted all of their gold as soon as his prophetic back was turned and made a Golden Calf. In vain did they plead that forty days and forty nights was a long time and they were a bit bored. Moses, not a bundle of laughs at the best of times, was not amused. He “burnt the golden calf in a fire, ground it to powder, scattered it on water, and forced the Israelites to drink it. When Moses asked him, Aaron admitted to collecting the gold, and throwing it into the fire, and said it came out as a calf”. They didn’t make that mistake again, I imagine. Most of them had digestive problems for weeks afterwards, apparently. Haven’t you got to love the Bible though? Aaron’s excuse reminded me of a boy (probably me) caught with his hand in the cookie jar. “Just counting them, mummy...honest”. Actually, things got quite a bit worse for the poor old Israelites. The Tribe of Levi had had the good sense (Teacher’s Pets!) to avoid Golden Calf worship. So Moses called them to him: “‘Whosoever is on the LORD's side, let him come unto me.' And all the sons of Levi gathered themselves together unto him. And he said unto them: 'Thus saith the LORD, the God of Israel: Put ye every man his sword upon his thigh, and go to and fro from gate to gate throughout the camp, and slay every man his brother, and every man his companion, and every man his neighbour.' And the sons of Levi did according to the word of Moses; and there fell of the people that day about three thousand men." I’m amazed they had survived drinking the liquid gold but old Moses, he was just making sure. Isn’t that some sort of Australian lager, by the way? |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Detail of the Lady Chapel screen. Note the unicorn crests to left and right Then, above the upper pair of rosettes) the left one broken off) little heads peering out. Think too of the intricacy of this carpentry and the skills needed. Right: The south wall of the Lady Chapel showing, on the left. the monument to Sir Robert Harling (d.1435) and on the right to Sir Thomas Lovell (d.1604). A study in the evolution of church monuments! Apologies for the bad light. Perpendicular windows were a boon to congregations but nobody thought of how bad they would be for photographers! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The weird and the wonderful of the English parish church. This is the tomb of Sir Thomas Lovell (d,1604) and his wife, Dame Alice (d,1602). There have been two very famous Lovells. One was part of a triumvirate of powerful henchmen of Richard III. The second was this Sir Thomas’s father and one of Henry VIII’s powerful friends and advisers, holding a dazzling number of positions and managing not to have his head separated from his shoulders. The Sir Thomas commemorated here, though, seems to have been something of a nonentity. Well in any event I can’t find out much about him! Sir Tom is arrayed in black armour and seemed to fancy himself a bit! Most bizarre, however, are what the couple have at their feet. Dame Alice has a pair of arms holding aloft the scalp of a “Saracen”. Why? This was centuries after the Crusades. Elizabeth I made lucrative trade deals with and accommodations with Muslim states such as Morocco. Quite a lot of middle eastern traders and craftsmen came to England. So why is this here? I can’t find or deduce an explanation. Meanwhile, Sir Thomas himself has peacock feathers at his feet. The flesh of the peacock was believed to be incorruptible. For more about the two more illustrious Lovells see my footnote. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Above Left: The head of Dame Alice Lovell. Above Right: In a church of peculiar imagery, this shield of three squirrels does not disappoint. Bottom Left: The monument of Sir Robert Herling (d.1435) in the Lady Chapel. Sir Robert’s military prowess is indisputable: he was killed defending Paris under the redoubtable Henry V. His wife was buried at the collegiate church at Rushford There were originally brass shields within quatrefoils below the effigy. Right: The tomb of Ann Herling and her first husband, Sir William Chamberlain (d.1462). She was Sir Robert’s daughter. This monument also doubled as an Easter Sepulchre. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The Robert Herling tomb chest is a mass of whimsical imagery. Unicorns, both sadly having lost limbs, face off over what looks like an armoured helm surmounted by an unidentifiable animal. Around the tomb there are decorative courses of fleurs de lys - presumably referencing Herling’s involvement with the wars in France and...baskets! Some believe that the baskets are fish baskets suggesting a fish of the herring family called a herling and thus a pun upon the family name. Right: Sir William Chamberlain’s coat of arms above his tomb shared with Ann Herling. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Three more Herling unicorns on Sir Robert’s tomb. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

These roundels are formed at the cusps of the arches of the Herling monument. Left: An eagle or falcon. Centre: A pelican in her piety feeding her young with blood from her own breast. Right: The carving is damaged but it appears to be an eagle with an animal within its talons. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The misericords. Heraldic designs are hardly a rarity but I have never seen a full set like this before. Even the supporters are coats of arms. I am not going to enumerate their features here. Heraldry enthusiasts will know where to find that information. But we see the unicorns, fish basket and fleurs de lys familiar in this church. Few churches show the long-term dedication of patrons on quite the scale that this one does. Yet somehow the patrons managed not to make it their personal chapel in the way that some did - the Rutlands at Bottesford, for example. The patrons at East Harling expanded the church’s space even as they left their personal imprints. If you are a misericord aficionado - and I certainly am - then you may be disappointed that we seen no vigorous representations of mediaeval life her; and no fabulous monsters or satire. They are a curiosities in their own right, however. In Northamptonshire the House of York was similarly represented in misericords from about this time at their church in Fotheringhay, although the symbolism was very much more vainglorious. It too was a collegiate church that was dissolved at the Reformation, losing its chancel altogether, and it too saw its now-redundant misericords rehoused in parish churches. For the best of them see the church of Hemington. The housing of such aristocratic artefacts in the most humble of parish churches is one of the great incongruities! Four misericords here is a meagre hand of survivors from Rushford Church. There must, one feels, have been more. It seems likely that the survival of these examples was at the personal behest of the families who are represented in the heraldry. Who know what mermaids, gryphons and misbehaving monks and ale wives were discarded? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

If the misericords are more interesting than exciting, then the armrest carvings more than make up for it. Highlights are the Wild Man of the Woods or “Woodwose” top left. Second left is the most fun lizard or dragon I can remember. Look at those very realistic eyes, the protruding tongue, the prehensile (my Pseuds Corner word for today) tail and the wings. This is a lizard you can reach out and stroke! Then we have another unicorn (second right) and a lion (far right). This carpenter had seen a real lion and I wouldn’t be surprised if he had seen a real unicorn as well! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

And so the fun continues. We have an eagle here as well as the ubiquitous pelican in her piety - see also above. The only slight cloud here is knowing - given the Church Guide’s teasing (and - frankly - annoyingly vague) reference to “indistinguishable” nineteenth century carving - that some of this might not be original. Which raises the old question of whether something is of less value if it is two hundred years old rather than six hundred? In this case, I think we just have to enjoy it all for what it is, regardless of age. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In truth, there are hidden treats everywhere you look in this Museum of Mediaeval Craftsmen. These six pictures are of the lower panels of the Lady Chapel Screen. Within the cusps the carpenters have left faces, animals and birds to delight us. It is not just the entertainment that they offer: look at how exquisitely they carved inside minuscule spaces. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

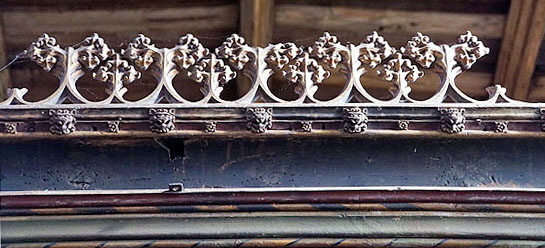

As with the lower parts of the screen, so with the upper. Again we have to marvel at he intricacy of the carving. Here we see, again, two unicorns on shields. They are fat little things - Thelwell creations. With apologies for that allusion to everyone reading this who is not both British and of a certain age! Notice you can even see individual chisel marks here. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

At the west end of the church are the surviving lower panels (the “dado” section) of the original chancel screen. They were placed here as recently as 1973 presumably because, the upper sections having been lost, they were rather a nuisance where they were! Needless to say, all is superb again. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The carved panels are worth looking at in detail. Left: We see here a helm surmounting the arms of the Mortimer family. There are a lot of branches of the Mortimer family. The most notorious branch was that of Wigmore on the Welsh Marches. Roger Mortimer (1287-1330), 1st Earl of March, overthrew the unpopular Edward II in cahoots with Edward’s wife, Isabella, and - so legend has it - murdered the King at Berkeley Castle in Gloucestershire by the insertion of a red hot poker into what is politely known as poor old Eddie’s “fundament”. It may be true. One of the many causes of Edward’s overthrow was his association with one Piers Gaveston who was widely believed to be Edward’s catamite. Thus perhaps the execution was seen to fit his “crime”. Mortimer himself was hanged - a pointedly ignoble end - by Edward III in 1330 after being de facto ruler of England for three years. Cecily Mortimer (c.1355-1423) married John Herling, although I suspect she was one of the Attleborough (Norfolk) Mortimers. Right: Yes, its another unicorn. This one is rampant and not at all Thelwell-like. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The survival of these panels might seem a little miraculous in the light of the Reformation. This crucifixion scene, however, tells us that the iconoclasts were here. All of the figures have been defaced. Christ, interestingly, is seen growing out of the sleeping figure of Jesse from who he was supposed to have been descended. Secular imagery was left intact and it seems that the despoilers destroyed the rood itself and probably the upper part of the screen but saw little point in destroying the dado. Right: The “IHC” monogram of Christ. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A with arms that are no longer distinguishable. Right: It looks like a central design is missing. What is left looks like the insignia of the Order of the Garter. |

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

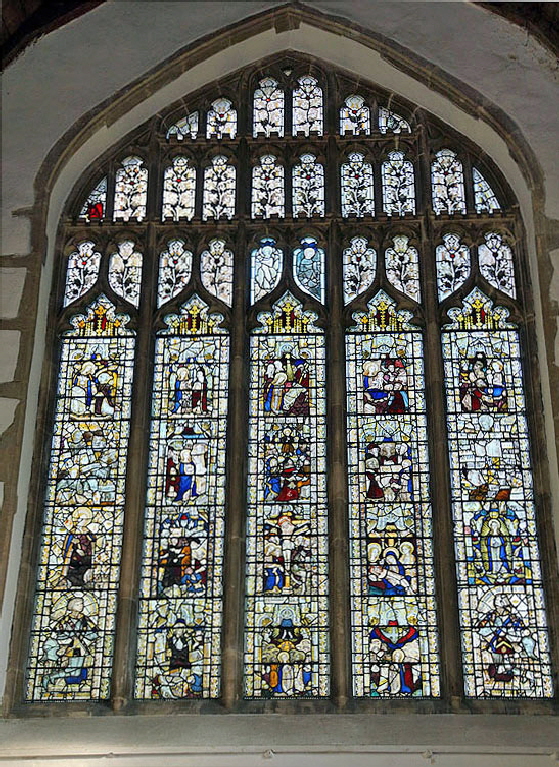

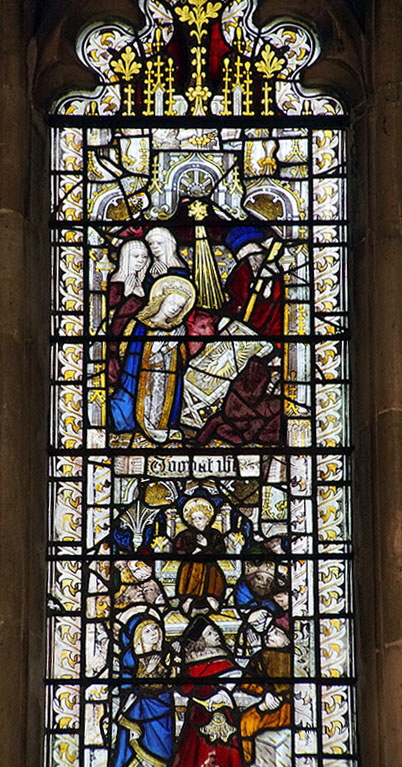

The magnificent East Window. I think it is not an exaggeration to say that this is one of the most important surviving mediaeval east windows in England. Right: The nativity above. Then Christ preaching in the Temple. |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Left: The top lights of the east window. The foliate designs are nineteenth century but the angels are of the mid fifteenth century. Right: Fragments of preserved mediaeval glass with, amongst other things, two coats of arms surrounded by the Garter insignia and a crown. |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Amidst a sea of outstanding craftsmanship, strangely it was these spandrel carvings in the south aisle roof that for me are the most awe-inspiring. Look at the unicorn (top left). This is prancing, noble, snorting unicorn carved by a man who could reproduce in wood the equine forms he saw in the aristocratic stables of Norfolk. This carpenter was not content to take the easy way out and make the creature’s horn part of the top beam: he carved it in beautiful proportions separate from the surrounding framework. Look at the delicacy of the carved leaves. His mastery of animal proportions is shown again in the bull (top right). Yes, you might take issue with some of the proportions - have you ever seen one of Stubbs’s horses? - but again this is a living, moving animal with muscle and sinew. The two lower carvings continue with the theme of family heraldry. Lower left is the most extraordinary. You might think at first glance that it is a stack of corn. In fact it is a set of women’s stays! The Playtex of the mediaeval world! Then we are back into the world of baskets (bottom right). |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A further array of East Harling woodworking virtuosity. Top Left and Top Right: Undersides of the Lady Chapel screen. Lower Left: The entrance lobby to the south door incorporates panels from old box pews, probably seventeenth century. It is fascinating to see not only a continuation of the tradition of fine wood carving here but also the use of imagery that would not have been out of place in a twelfth century church. Lower Right: More screen carving. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The unusual (although not unique in this area) eastern nave window at clerestory level. The opening below it is something of a mystery. Centre: There is little in this church that is ordinary but the fifteenth century octagonal font, I am afraid, is just that. Right: The coat of arms of the Lovell tomb. With squirrels. Mind you, squirrels were much fiercer in those days. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left Upper: Did you think I was just seeing things when I said that there was a carving of women’s stays in the south aisle roof spandrels? Well this is a collection of bits of mediaeval glass that and you can see two very good representations of said undergarment complete with laces necessary to almost cut women in half in the interests of pulling the waist in and pushing out those heaving bosoms that are so beloved of BBC costume drama. Oddly, the Church Guide makes frequent reference to “quivers of arrows” and I wonder if the celebrated Roy Tricker who wrote it (his services to East Anglian churches have been of inestimable value) was unfamiliar with female foundation garments? Me? I’m an expert! There are also four baskets, one of which seems to be surrounded by rays of the sun. Left Lower: Decoration at the top of the lady chapel screen. Those cheerful-looking lions with protruding tongues are as ubiquitous in mediaeval imagery as angels and grotesque faces. And much more so than baskets and stays! Right: A very pretty pillar holy water stoup. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The pretty south porch with its typical Norfolk flint “flushwork” is also fifteenth century but has been restored twice. Right: The extraordinary spire. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The parapets of the tower gave the stonemasons a welcome chance to get show their own carving prowess. These are also fifteenth century. The unicorn is shown on all four sides and their form here with their bushy tails is very similar to that in the spandrel of the south aisle roof. Also present is a bird which the Church Guide suggests may the chough emblem of Sir John Scrope. The statuary would be a fortunate survivor of Reformation and Commonwealth. Norfolk was Cromwell country and his Ironsides liked nothing better than a few statues for musketry practice. .Right: The church from the south east. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote |

|

East Harling made a big impression on myself and my church crawling companion that day. Everywhere you look there is something to photograph. Writing about it, however, was a revelation. That forced me to really focus on the art - and that is what it is - here in such profusion. It also made me realise that here we were getting a pretty complete look at the extent of patronage of churches by the mediaeval elite. Yes, of course, most churches have aristocratic connections but what struck me about East Harling was the symbiosis here: the elite poured money into the church and left their mark all over it without appropriating it. They buried their dead and they expanded the church for the benefit of all. There was it, it seems to me a deep sense of noblesse oblige. In a deeply rural area it is hard to imagine the sense of wonder and pride that the peasantry and farmers must have felt. I took what seemed an eternity to write this page - one of my longest - and I still think I missed things. Writing screeds about a single church can be quite a challenge to my mental stamina. I am conscious that I have been even more irreverent that usual in writing this piece. That keeps me from getting bored. I also like to think that our mediaeval forebears had a sense of humour akin to my own. The evidence is there to see. Lady’s stays, eh? If you are a very committed Christian with a deep sense that churches, the Bible and so on should not be the objects of levity from unbelievers such as I then I apologise and suggest that you skate over my many transgressions on this website! I do, as many of you will realise, take issue with many of Simon Jenkins’s ratings of “his” 1000 churches - and that’s before we get to the issue of what is included and what is excluded. In writing about East Harling I got a sense of why he so often surprises and disappoints. I have one hundred and fifty five pictures of this church and you are seeing half of them on this page. Simon’s book uses pictures from “Country Life” magazine at a rate of about one picture for every ten churches. That, of course, is the price “proper” authors pay for their physical books: colour photography pushes up the cost of publication at an alarming rate. Photographing a church - in this day and age most cameras and even phones are up to the job - makes you look for what is remarkable, makes you examine the minutiae and then, when you review your pictures, allows you to appraise calmly and to get past your immediate impressions. If this church is not on your “must visit” list, it should be. The Church Guide, by the way, is one of the best you will ever see. And take your b****y camera! |

|

Footnote: The Lovells |

|||

|

There is a wonderful satirical rhyme that has come down to us over many centuries written by a man called William Colyngbourne: “The Cat, the Rat and Lovel our dog do rule old England under a Hog”. The hog was Richard III whose symbol was a boar. The Cat was William Catseby. The Rat was Richard Ratcliffe and Lovell was the “dog” because of his family crest. They were Richard’s henchmen during his brief three year reign. Ratcliffe was killed at Bosworth. Catesby was executed after the battle. But Lovell escaped to Yorkshire and in 1486 tried to capture Henry VII when he visited the county. He escaped again to Burgundy and participated in the Lambert Simnel conspiracy. He may well have died in the Battle of Stoke in 1487. He was in a different branch of the family to the next prominent Lovell - Sir Thomas of East Harling who died in 1524. I am quoting here: (Lovell) enjoyed a distinguished career in service to the first Tudor monarch, King Henry VII, as a trusted adviser in political, financial, and military affairs. Among the many positions he held, Lovell was a Knight of the Garter, Chancellor of the Exchequer, Speaker of the House of Commons, Treasurer of the King’s Chamber and Household, and member of the Privy Council. He remained an influential figure during the early reign of King Henry VIII, serving as Constable of the Tower of London and Steward of the Household, and played a role in the French expeditions, but gradually retired, his age and opposition to the policies of Cardinal Wolsey leading to his eventual disappearance from the court of Henry VIII. Lovell had grown wealthy from his many salaries, and he acquired extensive real estate in East Anglia. The wives of Sir Thomas Lovell and his brother Robert were descended from the Lords Mortimer of Attleborough; real estate in Attleborough was owned and passed down through the Lovells”. Thus we can see the connections of the Lovells with the Mortimer family whose arms appear in the church. Sir Thomas was also, presumably, the subject of the appearances in glass and wood panelling of the garter imagery as well as the royal crown that is also shown in a stained glass fragment. |

|||