|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

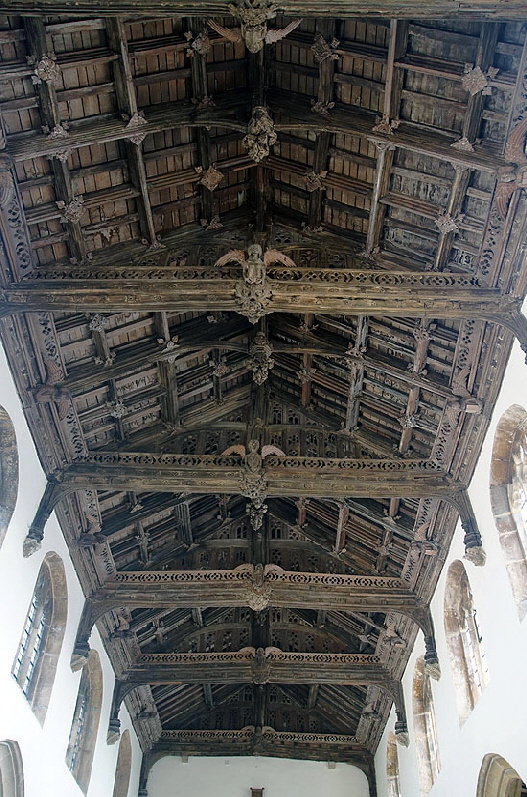

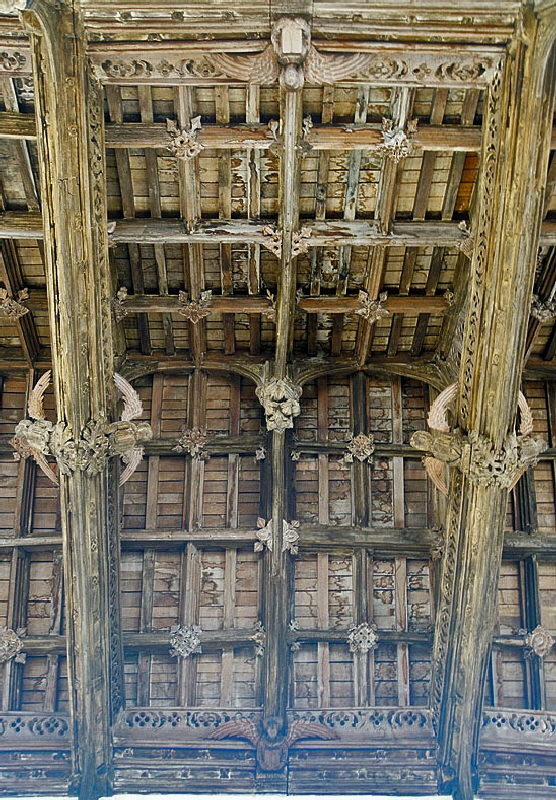

Justice Jeffreys. Others were executed summarily on gallows erected outside the church. More about the battle and the rebellion is in the footnote below. The church, a rebuilding of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, is a fine one of five stages mainly distinguished externally by its mighty one hundred feet high west tower. Its facings are in Blue Lias and Ham stone. There are two aisles and battlements abound, Weston was a wealthy settlement by this time, surrounded as it was by rich agricultural land reclaimed from the rivers. Sheep grazing on the wetlands doubtless also made a contribution to the prosperity. In truth, as a building it is “fine” rather and particularly interesting. The nave is lofty, the whole place spacious. One might say that it is a perfect example of “military medium” gothic high gothic architecture, albeit of somewhat superior coinstruction to most. What distinguishes it apart from its tower and its place in history, however, is its magnificent timber roofs. In the nave the tie beams are adorned with carved angels and pendants. It is a magnificent sight that will make you draw breath. |

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

The two glories of Westonzoyland church. Left: The top three of the five stages of the tower as viewed from the south. Three empty niches bear witness to the iconoclasts of Reformation or Commonwealth but one headless statue somehow survives. One wonders whether some Civil War sharpshooter fancied a bit of target practice? Each niche has an angel carved at its base. Pinnacles and battlements are in expensive style. There are gargoyles in the lean and long-legged style favoured by the Somerset masons and known in these parts as “hunky punks”! Right: A section of the timber nave ceiling with angels, carved bosses and pendants. |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the west end. Note the elegant arches uninterrupted by capitals. The rood screen dates only from the nineteen-thirties This is curious. Why did the church discover the need for a rood screen so recently? The Anglo-Catholic revival impelled by the Oxford Movement would doubtlessly applauded such a move but it was a nineteenth century phenomenon. This screen goes the whole nine yards, connecting with the old stairway (visible to the left of the screen) and has a cross (the rood) and supporting evangelists in the pre-Reformation style. It is a very strong statement, it seems to me, wrapped up in a cloak of “decoration”! The West Country rose in rebellion in 1549 against Cranmer’s reforms and especially his Book of Common Prayer and the outlawing of the doctrine of transubstantiation in 1549. See Sampford Courtenay for more about this. Cornwall and Devon have unusually large populations of rood screens (sometimes with roods reinstated) to this day. The nineteen thirties, however, is very late for reinstating a device that is now liturgically pointless. Right: Looking towards the west. Everything here is very ordered and symmetrical, reflecting a church that was rebuilt as a piece. It also demonstrates the late mediaeval preoccupation with light. |

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The south aisle has some displays about the Battle of Sedgemoor as well as a very informative short film. Right: Another view of the nave roof. |

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: One of the angels on the roof cross-beams. Right: These large pendants adorn junctions of king posts and tie beams. |

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Another view of the roof, showing the attractive design that conceals the west wall. Right: Rich decorative fan vaulting underneath the west tower, |

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The chancel with its typical West Country waggon roof. Centre: Another view of the south aisle with a reproduction of the Monmouth banner. Right: Apologies to all historical firearm enthusiasts if I’ve got this wrong but I believe the upper of these two muskets is a wheel-lock (that is, the lit fuse is rotated pivoted on a heel towards the powder pan and the lower is a flintlock where the powder was ignited by means of a spark from a flint. |

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Like many West Country churches, Westonzoyland has some nice carved mediaeval bench ends, although those here have no amusing, satirical or cheeky motifs - sadly! Right: Heraldry in a window. |

|

|

|

|

Left: This bench end has the initials “RB” for Richard Bere, Archbishop of Glastonbury from 1493-1524, allowing us to ascertain the church’s date. Centre and Right: The south doorway with what appears to be the original timber door. Bearing in mind that the church was used as a prison for the defeated Monmouth supporters, what misery and despair this door must have seen. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote - The Monmouth Rebellion and the Battle of Sedgemoor |

|

I read that Karl Marx (I am not a devotee) wrote that all guns had a worker at each end. I thought of that when reading about the Monmouth Rebellion. If you are not British or, let’s be honest, you are British and you don’t give a fig about our seventeenth century history then you might not have reflected on the religious turmoil of England over the course of the Tudor and Stuart dynasties. Henry VIII began it all by establishing the Church of England so he could be shot of the saintly (they said) Catherine of Aragon and marry the conniving whore (they said) Ann Boleyn. The twists and turns of his own religious ambivalence served to keep the population confused and worried until his successor the boy king, Edward VI, put an end to ambivalence by turning the established church decisively in the direction of Protestantism. Mary Tudor turned all that on its head making England Catholic again. Elizabeth I “sought no windows into mens souls” but felt compelled, rightly or wrongly, to be the sometimes persecutor of Catholics as an act of self-preservation. James I, was Presbyterian but had been baptised a Catholic. Despite renouncing acts of persecution, he maintained and even reinforced anti-Catholic laws. The Catholics responded with the abortive Gunpowder Plot. Then Charles I appeared on the scene, professing loyalty to Protestantism but encumbered by a wife who was anything but and who made little effort to conceal the fact. It would be a mistake to say that suspicion of Charles’s religious affinities were the pivotal cause of the English Civil war but Charles was the start of the Stuart dynasty that might be justly described as being remarkably stupid. Their wives were not much better. Despite espousing religious tolerance Cromwell was no supporter of Anglicanism. His religion was of a more austere nature of Protestantism but there is no doubt that he had a strong aversion towards Catholicism which stood for everything he despised. He did not descend into persecution although his savagery in Ireland was probably promoted in part by religious feeling. By the time Charles II returned England to royal rule, the country was very firmly Protestant. Charles II as we might say in England buggered along throughout his reign and was much more interested in debauchery than in religion. It is well documented that he received the last rites from a Catholic priest but his life was seemingly ambivalent in religious matters. He ran with the hare and hunted with the hounds, taking pensions from Louis XIV of France who was, of course, a Catholic and who was prosecuting a war against the Protestant Dutch States as well as repealing the Edict of Nantes in 1485. Louis thereby renounced religious freedom, causing massacres of the Protestant Huguenots in France. England was not impressed by this Anglo-French friendship.. Charles’s son James Duke of York, heir to the throne was, however, a devout Catholic. Most of the English population - probably more than 90% by this time - was firmly and irrevocably Protestant and had every reason to be fearful of a Catholic king. The line of succession was a massive fault line in Restoration politics. Henry VIII had been able to rule by diktat and execute his enemies, real or supposed. Post-Civil War England had a powerful and assertive Parliament that did not flinch from open conflict with the monarch. All efforts at compromise over the succession failed. Not least of Charles’s problems was that his bastard son, James Fitzroy Duke of Monmouth. was Protestant, charismatic and popular. Charles stuck to his guns, refused to deny his legitimate son’s right to succeed and in 1685 James II duly became king upon the death of his father. It is probably fair to say that by this time James II was something of a standout in terms of religion. Even his own sisters Anne and Mary were brought up as Protestants at the instruction of their father. Mary married William of Orange the de facto King of the staunchly protestant Dutch States. There is little to admire about James but perhaps his unwaivering adherence to his faith is one thing. He was, in short, a Catholic king in a Protestant country when their were three other possible Protestant monarchs. j James succeeded on 6 February 1685. It took only until 11 June for Monmouth to leave exile in Amsterdam and to land at Lyme Regis in Dorset at the head of a pitiful force of 150 adherents. Monmouth had made the usual fatal mistake of assuming that his popularity would translate into a popular uprising in his favour. The West Country had not expected him to land in their neck of the woods. Nor had James I who had sent his troops elsewhere. Monmouth did manage to recruit a force that peaked at maybe seven thousand from Dorset and Somerset but that was far fewer than he had anticipated or needed. Over the next twenty five days he won a couple of minor skirmishes with the royal forces but was then trapped in Bridgwater by a royal army under Lord Faversham, unable to make his planned march from Bristol to London. Faversham’s army made camp at Westonzoyland four miles away. A native of nearly Chedzoy made his way to Bridgwater and told Monmouth he could lead him and his troops through the marshes to make a surprise attack on the Royal encampment at night. A desperate man by this time, Monmouth must have sensed redemption. 3500 men silently left Bridgwater at 10.30 pm. The guide led to them through two deep drainage ditches. At a swampy ditch called Langmore Rine, however, the guide missed his way. He recovered but in the confusion a pistol was fired and so the element of surprise was lost and Royalist foot soldiers were waiting. The battle that followed was confused by darkness and difficult ground. The royal troops were in disarray and Monmouth’s men were in with a shout of victory but the coolness of some of James’s commanders contrasted with Monmouth’s own over-excitement. By dawn Monmouth’s army was beset on all sides. The rebels fled for their lives. What followed was not pretty. The royal troops, by now reinforced by the militia from nearby Chedzoy, pursued the rebels and indiscriminately slaughtered them in cold blood. Others, as we have seen, were imprisoned in Westonzoyland Church. Monmouth fled the field leaving the brave farm boys that had rallied to his standard to their bloody fates. He attempted to get to the south coast to take board a ship for France but he was captured near Ringwood in Hampshire. He begged his stepbrother for his life on bended knee but James was having none of it. How could he? Monmouth would have remained a a rallying point for disaffected Protestants had he lived. Monmouth had even offered to convert to Catholicism. It is said that James was somewhat disgusted at his abject demeanour. As a nobleman, Monmouth was executed by beheading. The notorious executioner, Jack Ketch - a name that was used as a pseudonym for other executioners for some time after his death - not for the first time botched his work. It took several blows and fearful injuries before Monmouth was agonisingly despatched. James and the courts showed no mercy to Monmouth’s officers and foot soldiers. Judge Jeffreys presided over the “Bloody Assizes” throughout Devon and Somerset. Jeffreys himself blatantly mocked the defendants and instructed the juries to find the rebels guilty. Two hundred and fifty were sentenced to death, eighteen hundred transported as slaves. Many died in prison. A woman was beheaded for giving food and drink to a rebel. Twenty nine were sentenced in Dorchester to be hanged drawn and quartered, a gruesome death. The two executioners complained that was too many for a single day. One wonders at the strength of their stomachs. |

|

What Happened Next |

|||

|

James II, despite professing tolerance towards Protestants, replaced almost all of the Bishops with Catholics. Catholics were appointed to his council and placed in all of the major government institutions. One can only presume that the treatment of Monmouth’s unfortunate and deluded foot soldiers only served to frighten the population, especially as James was still close to Louis XIV. Many Huguenot exiles found their way to London despite James’s attempts to stop them. Their stories of the atrocities following the repeal of the Edict of Nantes must have spread through the city like wildfire. James meanwhile maintained a “standing army” of fifteen thousand men. This was a new concept in England where armies were traditionally formed for specific campaigns and disbanded again afterwards, armies being a major drain upon royal purses and public treasuries. The populace must have felt that the main focus of this army was likely to be themselves. James was as ill-judged in his actions as his father and grandfather before him and persisted in pursuing pro-Catholic and pro-French policies. To stoke the fears still further, his wife Mary of Modena produced a son. Many disbelieved it. A story emerged that a baby had bees smuggled into the palace in a warning pan! The prospect of a Catholic dynasty must have seemed unbearable. William of Orange, husband of James’s Protestant sister Mary watched and waited in the Netherlands. He prepared a fleet. Louis warned James of this but with typical Stuart pig-headedness James chose to disbelieve the news, feeling that William was too preoccupied with his war with the French.. On 28 September 1688 William announced his intentions to invade, citing much support and encouragement from the English nobility. Panicked, James tried to retrieve the situation, dismissing his Catholic advisor and promising to preserve the Church of England. It was too little, much too late. William sailed in mid-October, a time when the seas were likely to be perilous. Indeed it was a perilous venture all round. James had bolstered his army by withdrawing soldiers from Scotland and Ireland. No invasion of England had succeeded since 1066. William surely knew that Monmouth had been disappointed in the support he received. The English navy waited in the Channel. James expected the invasion to be in the north and east - a reasonable assumption. Instead William headed to the South West as had Monmouth before him. Adverse winds affected the Navy’s ability to pursue him and in any event the Dutch fleet was felt to be too tough a nut to crack. William landed unopposed at Brixham in Devon on 5 November 1688, eighty three years to the day since the Gunpowder Plot had tried to instigate a Catholic insurrection. His invasion was slow to gather local support but in time pro-Protestant risings occurred in Nottingham, Leicester, Carlisle and York. James was ill, suffering catastrophic nosebleeds, and racked by indecision. This gave time for some of the nobility to defect to William, amongst them John Churchill who would one day achieve military glory in the War of the Spanish Succession and be created Duke of Marlborough under another Stuart monarch, Queen Anne. Anne herself, a staunch Protestant and no fan of her brother, fled to Nottingham. Without engaging William’s forces, James decided to retreat to London. There he recalled Parliament but few answered the call. In an atmosphere of distrust and anarchy and with few remaining supporters, James decided to flee. He was apprehended when about to sail from the Isle of Sheppey in Kent, ironically being mistaken for a Jesuit priest! Dutch soldiers meanwhile had arrived in London. Nobody knew what to do with James so he was allowed to make his way to London where on 16 December crowds greeted him enthusiastically. At Whitehall Palace he was to discover that all the guards were Dutch and he was effectively prisoner in his own palace. William arrived in London the next day but commanded James to be out of London so as not to “confuse” the London crowds. If James saw this as an indication that William did not feel fully secure he evidently was not in the mood to gamble on the support of the Londoners. He repaired to Rochester and, probably with the collusion of William, found himself in a position to escape by skiff on the River Medway and thence to take ship to exile. So ended the reign of England’s last Catholic monarch. Britain’s constitution still does not allow for another; a somewhat anachronistic and unnecessary stricture you might feel but one unlikely to require amendment as long as the House of Windsor continues to produce heirs and innumerable superfluous spares. The hereditary monarchy itself is the great anachronism and any reform of the constitution is more likely to be looking at its role rather than at its religious leanings. William III and Mary reigned peacefully to be followed by Mary’s sister Anne. Neither left any heirs. Her second cousin, George of Hanover, was deemed Anne’s closest Protestant relative and was crowned George I in 1714. Considering all of England’s previous agonies over lines of succession, this was a remarkable development and showed the lengths England would go to ensure a Protestant monarchy. The Young Pretender “Bonnie Prince Charles”, grandson of James II, challenged this with his rebellion in 1745 but after some early success and progress as far as Derby it ended with a bloody rout at the last battle on British soil at Culloden. Britain’s army by now was a permanent one and it had much experience of fighting in Europe’s continental wars of the early eighteenth century. Not only was the Stuart line now history but it was also the last realistic chance of an armed rebellion challenging an established monarch or government in Britain. It is extraordinary to think that Henry VIII’s controversial and unpopular break with Rome would be the precursor to changes that would within a hundred and fifty years lead to to a country so opposed to Catholicism that it would crown first a Dutchman and then a German as King. It is worth listing the religious ups and downs of England after the Reformation to get a sense of the challenges faced by the population. |

|||

|