|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

of tea and socialising. I thought at the time, as I am sometimes wont to do, “this is my England”. The people of Quenington were not about to let a worldwide pandemic disturb their sang froid. And it’s about time we got a non-Gallic synonym for that, by the way! |

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

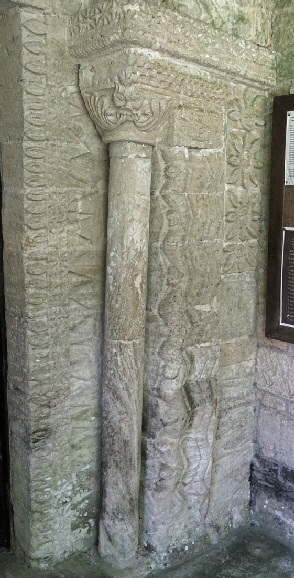

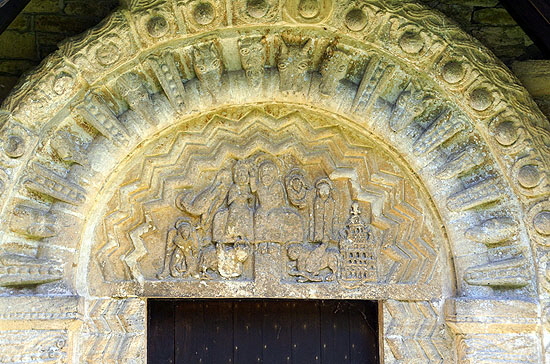

The north doorway. This is the marginally less interesting of the two doorways, although both are splendid. The decoration on the jambs (right upper and lower) is exceptionally elaborate, somewhat unusually outshining the fairly run-of-the-mill decorative courses around the arch. Interestingly, when I read Pevsner I found he supported my own suspicion (as far as one can confirm these things) that the tympanum - and I also I would suggest the innermost jambs - pre-date the rest of the surround. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

The north tympanum is weathered and depicts Jesus slaughtering three meerkats. It is said that he bought insurance from Comparethemarket.com and subsequently realised he could have bought it cheaper elsewhere, and took umbrage. Ok. I made that up. The depiction, in fact, is of the “harrowing of hell”. This is a theologically dodgy notion that between his death on the cross and his resurrection, Christ descended into hell whereupon he granted salvation to virtuous people who had previously died. In the process, of course, he had to slay the odd Devil and Demon as depicted here. The three meerkats, one presumes, are actually tormented souls pleading for salvation. Scriptural references to this incident are oblique, to say the least, and the most positive mention of it was the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus (that is to say it was not incorporated into the New Testament) that despite its perceived shortcomings as a narrative was still widely read. How good people landed up in the fiery pit in the first place is a matter of considerable scriptural gymnastics involving both testaments (nothing unusual there) and I am not going to venture into such arcane areas. Without being too cynical, it appears that the early Christian authorities were anxious to fill up the three day gap in Christ’s narrative and this was a convenient and plausible (religiously speaking) answer. The best depiction of the harrowing is on the Norman font at Eardisley in Herefordshire. |

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

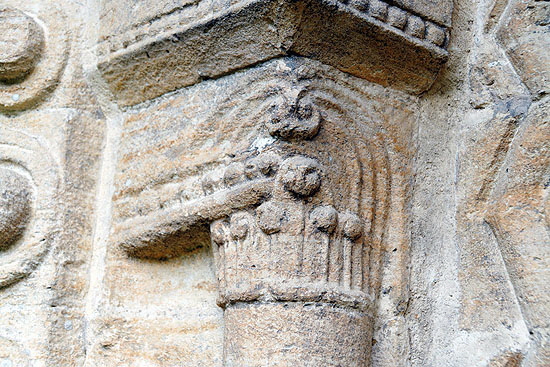

Left and Right: Both the north and south capitals of the north doorway have mask figures and interlace designs surmounted by geometrical designs. |

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

The south door does not look to be contemporary with the north. It has virtually no capitals. It has similar broad bands of decoration, however, and a course of beakhead decoration around the tympanum. |

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

The tympanum represents the Coronation of the Virgin. This is, like the harrowing of Hell, a thing of dubious scriptural provenance. Mary is crowned Queen of Heaven by the central figure of Christ. The four evangelists in their winged form can be seen. To the right is a building that Pevsner suggests as the “Heavenly Mansions” or, I would suggest, the City of God. Both, again, Church constructs rather than scriptural. The building with its dome is clearly Byzantine in style, once again suggesting ideas being brought to England by the Crusaders. There is a similar representation on the font at Southrop only four miles away. |

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The south doorway with its outer mouldings. Right: Within the church a number of Norman fragments are preserved on the nave walls. |

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the east end. It is a simple single celled building now, straight through and inoffensively functional. Only the depth of the window splays to left and right betray its Norman origins. Right: The church from the south with its Norman doorway peeking from underneath the porch. Note the Norman string course. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||