|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

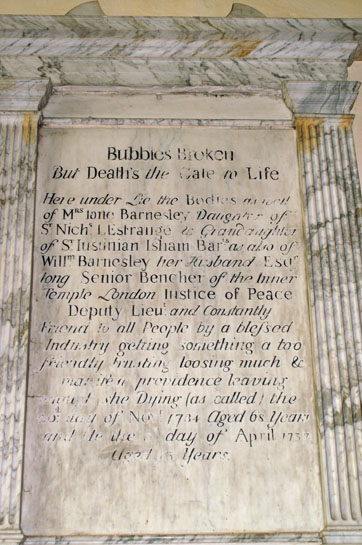

The Baskervilles (from Basqueville in Normandy) of the c12 had a poor reputation. Henry II reputedly said “If there were only one Baskerville left in Christendom that would suffice to corrupt the whole mass of humanity”. That was the trouble with Henry, he would mince his words so...! Is it coincidence that Conan Doyle chose a Baskerville to own his “Hound”? Anyway, in 1127 Sir Ralph de Baskerville fought a duel in Hereford with his father-in-law, the Lord Drogo of Clifford Castle whom Baskerville alleged to have stolen some of his land. Baskerville killed his adversary and was forced to buy a pardon (as the rich were wont to do in those days) from the Pope And, it is believed by some - that this battle is commemorated on the Eardisley font! It’s a good story and, who knows, it may be true! Property disputes also blighted the life of William Barnsley who became Lord after the Baskervilles. He was involved in litigation with his son over a period of 34 years and this quarrel is believed to have been the inspiration for Charles Dickens to create the endless disputes of the Jarndyce family in “Bleak House”! William’s memorial tablet wearily records his travails. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The key religious theme of the font is the “Harrowing of Hell”, and on English fonts it is unique to Eardisley. There was theory that after his death, Christ descended into Hell for the three days before his resurrection. This is a development of the “Ransom Theory” of man’s salvation. The “harrowing” has scant scriptural support, to say the least, and probably emanated from the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodaemus of about AD150. To see more about the Ransom Theory as described by the late Mary Cutis Webb please click HERE. In essence, the font depicts Christ, His cross planted firmly in the ground, rescuing virtuous Man - presumed on this case to be represented by the figure of Adam - from Hell. It is worth mentioning that there is a theory proposed by Malcolm Thurlby in his indispensable book “The Herefordshire School of Romanesque Sculpture” that the rescued figure was Ralph de Baskerville. This fits, of course with the notion that the font also depicts a fight between Baskerville and Lord Drogo - see below. Surely, though, Baskerville would hardly have been represented with a halo!? I respectfully have to dismiss that notion. At Christ’s shoulder is a bird that most “authorities” assume to be a dove. Mary Webb, however, explained that in the first millennium Christ was routinely represented as a “Sacred Bird”, even as a vulture and the Eardisley bird does indeed have a vulture-like beak so I am inclined to believe that she was right. To the right of Adam is a mass of tendrils and behind that is a large lion-like figure. There is debate about this figure but most believe it to represent Hell. Similarly the figure to the left of Christ is variously named as God the Father and John the Baptist. Mary Webb believed the tendrils to refer to the encumbrances man experiences in reaching God through his “dissolute mind” and “loose practices of their behaviour”, as expounded by Pope Gregory the Great. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This is clearly meant to be a lion. The mason obviously had only the scantiest knowledge of what a lion looked like but a thousand years later we can nevertheless be in no doubt about what he intended. The carving is so distinctive that there is no doubt at all that this man also carved the equally-famous font at Castle Frome which also has a lion, albeit a winged version representing St Mark. Shown entangled with the tendrils it seems that the lion represents the forces of evil. Right: The splendidly vibrant “Baskerville and Drogo” figures. It’s a strange tableau. “Drogo” (left) has sword in one hand but the other is clutching at the tendrils of what are likely to be the a representation of evil - a common theme on fonts. He is surely holding a tendril in one hand in order to slice it with his sword? But is “Baskerville” thrusting his spear through the other man’s thigh? If so, this scene is at best ambiguous and maybe supports the “duel” theory. Or is he piercing a tendril of evil and the spear is behind the other man’s leg? Note their clothing: they are not wearing armour but are clad identically in loose pyjama-like gear. This is hardly military garb. Is this just two ordinary men fighting with evil? I am inclined to discount the “duel” theory, attractive as it is. The clincher for me is the tympanum displayed at Billesley in Warwickshire which without any shadow of doubt was carved by the same mason. See the picture at footnote 2 below. The man there is dressed identically and is not fighting another man. He is also entangled with tendrils. He is apparently being pursued by a beast (surely the Devil) and struggling to reach a bird - surely a representation of Christ ”the divine bird”. It seems likely, then, that these carvings are variations on the same theme. Indeed, it is at least possible that the Billesley tympanum was originally carved for Eardisley. The Harrowing of Hell was not an everyday biblical concept: there is only one very oblique reference to it in the Bible. Eardisley’s is the only font in England to have this theme. Did this concept come from the head of a common mason? Had he read the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodaemus? Of course not! I have already mentioned that we can trace this man to Castle Frome. Malcolm Thurlby has also traced him to Hereford Cathedral. It is from the monks of Hereford that this mason surely received his biblical instruction. So, ask yourself: would the monks encourage the mason to put the rather wicked Lord Baskerville on a font and to give him a halo? No, I don’t think so either. It’s a great story but I think it is fanciful. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Detail of the carving around the base of the font. Right: After the font, the church is somewhat prosaic, albeit pleasing to the eye. This is looking towards the east. The chancel dates from around 1300. The windows are surely more recent |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking to the west where a coffee morning was in full swing! To the left we can see the late Norman rounded arcade arches, and to the right the c13 pointed arches of the north. Right: The Norman arches are very plain but, interestingly the columns are square rather than round. There are no capitals at all, just simple impost blocks. The easternmost bay is the original opening from the original chancel to a side chapel. The clerestory was added in around 1330. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The arcade to the north aisle. Right: This window sill at the east end of the south aisle incorporates a carved stone block. The church guide speculates that this is a fragment of an original carved doorway of the Hereford school. When I read this, my mind went to the church of Bredwardine where I had photographed the north door the following day. Please follow this link to see my speculation about a connection between these two churches. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The north doorway of Bredwardine Church. I believe this totally vindicates the supposition that the window slab at Eardisley was originally part of a similar doorway. Right: Eardisley Church from the south. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Centre: Rather lovely carvings of Bishop and King. Right: The monument to William Barnsley, rather poignantly headed “Bubble’s Broken But Death’s the Gate to Life”. It goes on to talk of “...Constantly friend to all people by a blessed industry getting something a too friendly trusting loosing much...” Poor man! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote 1 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Herefordshire School of carving is one of the most intriguing topics in the history of our English parish churches. Much has been written, including the splendid book “The Herefordshire School of Romanesque Architecture” by Malcolm Thurlby. Much of the carving we see is undoubtedly symbolic and not, as it would be easy to assume, simply the whim of the carver. In this regard, I must point you towards the work of Mary Curtis Webb whose astonishing - and sadly unpublished - studies demonstrate the classical Greek influences upon many Romanesque carvings in England. Please do visit my webpage which discusses some of her work, specifically concerning the North West Norfolk School of Norman fonts and which also includes some suggestions by both myself and fellow church historian, Bob Trubshaw. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote 2 - Billesley Church |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Billesley Church in Warwickshire has a Norman tympanum on display and it clearly is the work of the man who carved the Eardisley font. Please click here to see my webpage. A picture of the tympanum is shown below. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A Word of Thanks |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Hereford school churches tend to be in out of the way places. We were a little dismayed when we arrived at Eardisley to discover a well-attended “Coffee Morning” in full swing. Worse still, when we entered we found the font covered in bags, paper plates, plastic cups. Fortunately, the ladies offered to move them all so that we could take photographs. After we had “done our thing” we sat down for a coffee and a piece of home-made cake, had a chat with a couple of the ladies and were made to feel very welcome. How nice to reflect that 800 years after this church was built, through all the changes of religion and all the modern challenges to “faith”, the church is still a centre of life, social as well as spiritual, in this small village. Our thanks to all for making us so welcome. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||