|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

door its main entrance at a time when many rural populations still reluctant to use the north, or “Devil’s” side. The chancel arch too is original and is conspicuously plain. It too has has the appearance of being Saxo-Norman with its deep crudely-decorated impost blocks. It is simple and timeless. One must visualise a very simple church indeed. That simplicity has not been sacrificed during the thousand years of its history. The Early English chancel has similar elegant restraint and complements rather than jars with the nave. To all of this, later generations bolted on the porch, bell cote and a fourteenth south transept. The west window too is later Gothic but compared with the depredations suffered by many Norman churches, this one has got off lightly indeed. But it is the font that will bring you here. I think of myself as a connoisseur of Norman fonts and this one is amongst the very best. Unusually - uniquely, in fact - I am not going to describe it because the churchwarden has done a wonderful job of that and with his permission, I am reproducing it. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The church from the south west. Note the large expanse of herringbone masonry, a Saxo-Norman trope. The north doorway is Norman but the head seems to have been given a slightly pointed profile later. Original too the Norman lancet window, but the double-light window to the right is clearly neo-Norman and seems to have replaced a larger (presumably Gothic) one. A similar window is set into the south wall. The boiler house seals the unusual status of the south side as being the unloved one here, possibly because it faces away from the village and the adjoining hall. Right: The chancel with its trio of simple early English (early thirteenth century) windows. You can also see the neo-Norman window in the nave, |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The slightly unusual Norman north doorway. It is later than the nave and the arch is Transitional in appearance with its roll mouldings and simple pellet decoration. The tympanum does not look quite right and tympana were out of fashion at this time. I suspect it was inserted later, but either way it has the look of an rather unsophisticated afterthought. Centre: The church looking towards the east. The twin Early English east windows are nicely framed by the chancel arch, I like to think by design. The arch is rather underpowered in terms of its height, presumably because the nave walls were raised to accommodate the height of the later chancel. The arch to the right leads to the south transept. Right: The west end with Perpendicular style window and the Norman font below. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The chancel arch looking towards the west. There are nineteenth century squints to both left and right of the arch. It has been speculated that these replaced mediaeval ones, I find the them rather odd. Why would squints be needed at all in such a small church? And even if one was needed to allow the clerk to toll the bell to mark the raising of the Eucharist, why was one needed each side of the arch? And if the Victorians changed them then why? Something doesn’t quite add up! Right: The simply decorated through stone of the chancel arch. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The very pretty chancel with its Early English windows. Right: The north door, Norman lancet window and faux-Norman double light. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The south side and the south transept. Right: The church from the south east. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Stone Effigies of Sir Thomas Conway and his wife, Elizabeth dating, according to the Church Guide, to about 1605. They originally sat atop a tomb in the south chapel. The costumes are very obviously Elizabethan but the Church Guide says that the costumes are from a slightly earlier period. Perhaps this was why Pevsner dated them to 1560? |

|

|

||||||

|

Left: This is a very interesting item, as explained to me by the churchwarden. There are many rumours around the country about “secret passages” in and out of churches but they are almost certainly a mix of folklore and wishful thinking. Except this empty tomb niche really did conceal a secret passage from the church to the cellar in the manor house. It has now been blocked up. What was it for? Well that’s anybody’s guess. Surely the most likely explanation is to do with Catholic recusancy in the Elizabethan era. Were traditional masses being said secretly in the church? Did the people in the manor harbour Jesuits? Right: The west capital of the south doorway. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

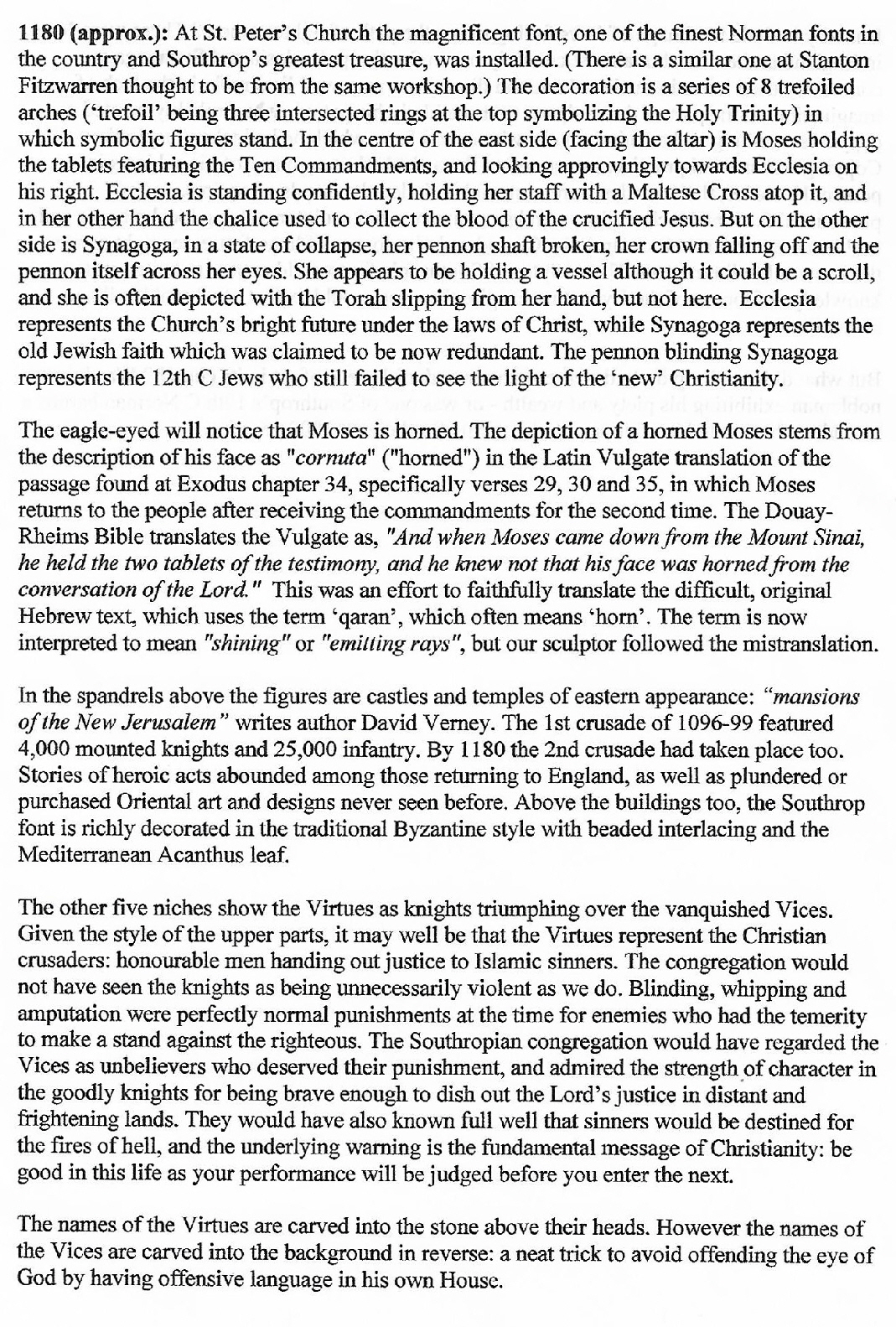

Left: The font. It has eight arches. Five are inhabited by personifications of the “virtues”, Each is in martial dress, having conquered the “vices”. Moses and Ecclesia occupy two more. The last is occupied by Synogoga. Each arch has the name of the subject conveniently incised above it. Right: Not least in terms of interest are easily-overlooked designs within the spandrels. These are all of buildings that clearly owe nothing to Western European, let alone English, practice. There are domes and cupolas unknown in England. They are surely designs that emanate from what was observed during the Crusades and might be compared with the exceptional chancel arch capital at Wakerley in Northamptonshire. Did masons themselves serve as soldiers and bring these designs back with them? |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Temperance (with anachronistic round shield) conquering Luxury. Centre: Generosity (with Norman style kite-shaped shield) triumphing over Avarice. Right: Pity conquers Envy. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Modesty defeats Excess. Centre: Ecclesia with bishop-like paraphernalia. Right: The most interesting sculpture in my view. Synagogia has her eyes blinded by a pennon representing the “failure” of the Jews to see the light. The antipathy of Christianity to the religion of Christ and from whom it appropriated the wholly Jewish “Old Testament” is, and sadly remains, surely the inexplicable and irrational of all of the contradictions inherent in “The Faith”. I am sure there is somebody out there that thinks they “get it” Me? I’m bemused. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Patience scourges Wrath, Centre: Moses. He wears horns which you might find rather curious. For an explanation see the text reproduced below. Right: the font in all its glory. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

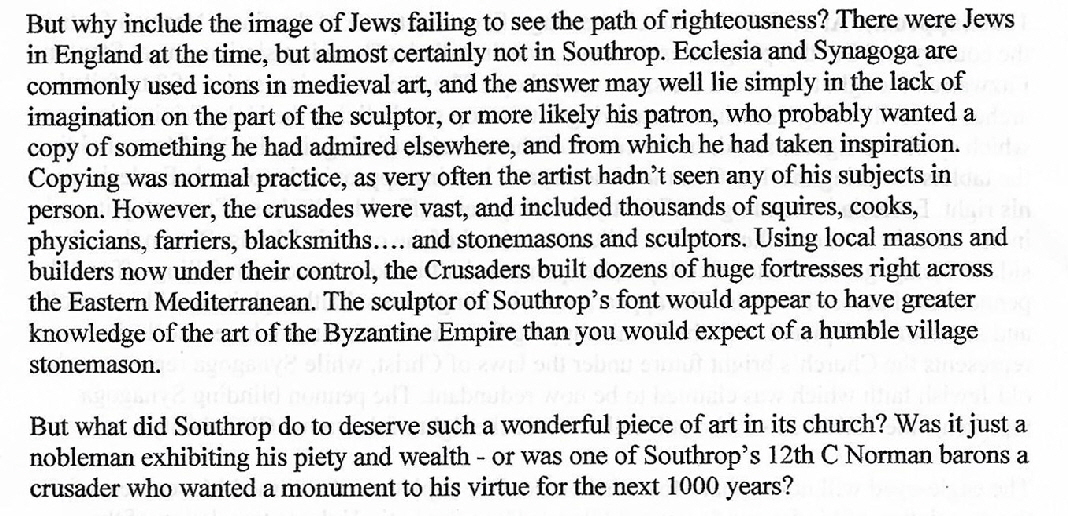

Left: A more familiar building to western eyes, you might think. But battlementing would still not have been very common in Norman England. I suspect this is more likely to represent a city wall in the Holy Land. Right: As with so many Cotswold churches, bale tombs in mellow limestone add a pretty backdrop. |

|

A Description of the Font |

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

Footnote: Donations via Smartphones and Other ways |

||||||||

|

Southrop was the first church I visited where there was a little machine on prominent display whereby you could simply swipe your mobile and thus make a default donation of óG5, I saw this at several Gloucesterhire churches and recently at one or two outside this area. While Diana and I were at Southrop a young couple came in, They had just “popped in” from the hotel across the road to have a look. In my usual importunate way, I pointed out the highlights, especially the font, on the grounds that there is little point in popping in if you haven’t a clue what you are looking at. I suppose they were there less than ten minutes. As they left the young man swiped his phone across the terminal as casually as adjusting his collar. There are two lessons from this. Firstly, too few churches make it easy to donate. A friend with whom I often visit churches is a generous donor. In fact, she upped my own game, I am slightly embarrassed to say. She always want to gift aid but invariably has to ask a churchwarden or vicar - who are rarely there, of course - where to find the envelopes. Worse still, it can sometimes be hard to find where to leave cash donations. Wall safes, ridiculously, are often Victorian and designed for a time when a slot for a penny would have been enough! Or you are expected to leave cash on a plate where any casual visitor could steal it. When I studied marketing (you can only imagine my limitless skillset ;-) I learned many valuable lessons. One was “Always be prepared to receive a customer’s money and take it in whatever form they offer it”. Cash is no longer the answer. Even myself I am often short of cash or need it for car parks. Many young people hardly carry any especially since Covid-19. The machines I saw at Southrop are definitely the way to go and it leads me to my second lesson, (from the Gospel according to Lionel Chapter 1 Verse 2): That óG5 default donation set an expectation level. Digressing, I am always a bit miffed when out with a dining group of which Diana and I are members at the miserably small tips some people leave. No matter how many times we gently suggest that 10% is the norm and really helps serving staff often on the national minimum wage, there are those who think it is ridiculously generous or who penalise the waiting staff for something beyond their control. Cue much sleight of hand to deposit a measly pound or two on the tip plate. This is not the place for debating the morality of the tipping culture but the point I am coming to is that most church visitors have no idea what represents an adequate donation to reflect the needs of the church they have enjoyed, That óG5 default (you are able to change it, I believe) sets an expectation level and makes it easy to reach that expectation. Or at least to make someone think a bit harder about leaving without making any donation at all. Many cathedrals are now rather good at extracting hefty “voluntary” donations. Parish churches don’t have the facilities to do that but they could do so much more to help themselves, Most people, believe me, think that churches are somehow funded by “The Church” that has limitless funds. When the reverse, in fact , is true. Here endeth the lesson. |

||||||||