|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There must have been a Norman church here and quite possibly an Anglo-Saxon one. There are those that still believe the font to be Saxon but that theory seems to be largely discredited now - rightly, I think. The church seems to be have been completely rebuilt in about 1300-1320, possibly by Sir John Carew. There is no sign of any old masonry being incorporated into the building. For my money that rules out the existence of a Norman west tower because mediaeval builders were reluctant to replace such monumental structures. The rebuilt church has chancel, nave, west tower and symmetrical transepts to north and south. It’s pure speculation on my part, but I wonder if the Norman church was a cruciform structure with a central tower? Central towers were a notorious source of trouble because Norman masons rarely understood the need to dig much deeper foundations beneath such a heavy structure. Maybe that was why Luppitt was rebuilt? Anyway, there are still two transepts and they share a common roofline with the nave which gives a pleasing appearance. The effect is even more gratifying on the inside. The lofty wagon roofs of the nave and transepts meet in the middle to produce what Pevsner rightly calls a “tent-like effect”. It gives a wonderful sense of space and continuity. In the middle sits a green man boss. It is a replacement for a worm-ridden original but that needn’t spoil it for you! There was a lot of restoration carried out in the latter half of the nineteenth century but don’t let this put you off: this is the English parish church at its best in a lovely setting - and, oh, that font! |

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

Left: The view east. The text over the arch was painted in 1991 replacing one that was overpainted by decorators in the 1920s. “Well, guv, you didn’t say nothing about keeping no inscription....” Right: The chancel. |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the west from the chancel. The font can be seen in the background. The walls are rather bare but I much prefer that to naff funeral tablets personally. Right: The superb crossing roof. Note the way timber ribs spring from each corner to meet in the middle in the manner of a Norman rib vault. |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Left: The eastern face of the font is this church’s most famous icon. Two men are going at it hammer and tongs with shields in their hands. Bizarrely a human head is shown between the two. What can it mean? The Church Guide suggests “An early Christian saint was betrayed by a friend, and was murdered by a pagan chieftain”, as proposed in the 1920s by Dr C.A.Ralegh Radford. The detailed explanation is too long to reproduce here, but it is an extraordinarily contrived interpretation with not a shred of evidence to support it! John Campbell of Plymouth wrote a detailed reinterpretation of the font in 2013. Noting similar fight scenes on the fonts at Eardisley in Herefordshire and Wansford in Northamptonshire, he speculates that it represents the story of Cain and Abel and that it is Adam’s face that appears between the two. He suggests that this, the first murder, was an appropriate design for a font that was meant to facilitate the washing away of original sin. Unfortunately, I no longer believe that the Eardisley font does represent two men fighting (I explain why on my webpage). John Campbell himself admits that the biblical account of Cain and Abel implies cold-blooded murder and not a fight, suggesting that the mason felt an urge to dramatise the story. With no disrespect to the promoters of these theories - after all, I have none of my own - I remain unconvinced. Francis Bond who wrote the definitive work on Fonts in 1908 suggests that a huge nail is being driven into the head in between the two standing figures and that this is a martyrdom scene. That was clearly nonsense. The body position of the right hand figure is of a man who has just struck a blow from right to left, not downwards and it is surely obvious that both men are holding shields? Yet those “weapons” are not the lance or sword of the Norman soldier such as are shown at Eardisley. They look more like tradesmens’ tools being turned to murderous use which is more in line with John Campbell’s ideas. Right: We are on more secure ground here with the north side. The figure on the left is a representation of a centaur (a horse’s body with a human head) carrying a spear. If he had been carrying a bow and arrow it would have been a Sagittarius. His body is wrapped around the east side (see picture left). It is an extraordinarily vibrant representation. On the right is a two headed monster. The Church Guide calls it an “amphisbaena” and days the two heads represent duplicity. Well anyway it’s clearly not one of the good guys! Wow, those teeth! Centaurs and Sagittarii are nearly always represented fighting with some other fabulous beast. I’m never quite sure where centaurs fit into Christian iconography. They originate in Greek mythology and were generally represented as wild and lustful. I agree with John Campbell’s observation that there is no obvious signs of conflict between the centaur and the amphisbaena on this font. |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Left: The south face shows a group of five beasts - we have to assume everyday animals rather than fabulous ones. Top left is a bird pecking at the back of a wolf-like creature. Below the wolf is a hound chasing a hare. Below the wolf is a loop design. Or is it the wolf’s oversized penis? I presume not. Right: The west face is simply a mass of tendrils in no apparent order. The Church Guide, again informed by an early twentieth century interpretation, suggests that the animals constitute a “hunting scene” and the west face “the afforested area”. Again, I struggle to make sense of this. Dogs chase hares or rabbits without our calling it “hunting” which implies human involvement that is missing here. Men hunt with birds but there are none that could take on a wolf or any other apparently ferocious creature. |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Left: Pevsner memorably described the font as “barabarous” and I suppose this is the sort of thing he had in mind, although I have to say that his comments on fonts and carvings tended to be a bit lacking in insight. This corner carving, though, was surely what he had in mind. For my part, I would prefer the term “vibrant”, though. What is fascinating is that you can see these square, bulging-eyed. big mouthed figures in many civilisations. Think Maori, Native American or Mayan for example. The tendrils of the “afforested area” and others in the vicinity of the two-headed monster seem to emanate from his mouth. Is this a green man? Do the tendrils represent lies and deceit? Right: The corner figure here (each corner has one) is like the beakhead carvings that decorate many a Norman doorway or chancel arch. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This view of the north east corner of the font allows us to see the centaur in his entirety. To the left of the human head is a rather strange cluster of three strands held together at the base. Is it the centaur’s tail? Could the mason not fit it into his scheme in such a way as to make it emanate from the centaur’s rump? Right: The font looking eastwards down the nave. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Continuing the theme that some of these carvings are reminiscent of other first millennium civilisations, these two carvings to the left of the fighting men look remarkably like those carved on totem poles. Centre: Luppitt’s “other” treasure is this Norman pillar piscina. There is one head at the top and the rest is stylised decoration. It is a fortunate survivor given that there is another fifteenth century piscina in the church. Is this one carved by the man who carved the font? I have been a bit surprised to see nobody discussing this possibility. It is really hard to tell. We only have the one head to look at and the font is not carved in a single consistent style. The only clue is that the piscina has very protruberant “tombstone” teeth and at least two face carvings on the font also have these. It’s hardly QED, I’d be the first to admit, but I think there is a case to answer. The Church Guide says that it was discovered within the chancel walls in the rebuilding of the 1880s. Right: The church calls this the “Angel Gate”. An architect suggested that the tower staircase needed better ventilation to combat the damp. So they replaced the previous solid door with this iron one. Showing an angel holding a bell, it was designed and made by a Mr Matt Dingle. I think this is a quite splendid piece of modern art. Luppitt Church’s custodians seem over recent years to have had an admirable sense of what works and what doesn’t; what enhances the church and what detracts from it. They should offer training courses, in my view.... |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The choirs stalls were acquired from Chagford in 1923. The Church Guide doesn’t make too much of this feature but the metal supports for the desks are delightful. I am a devotee of mediaeval bench carvings but sadly many Victorian and even twentieth century ones manage to be rather tasteless parodies. This design does not fall into that trap and combines modern decorative ideas with practicality. I think the Arts & Crafts movement would have approved. Right: The Green Man roof boss. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Doors, doors, doors....Left: The south door. There are carved heads on either side of the door. The notice telling you that the church is open is what every church crawler hopes to see. Centre: The priest’s door on the south side of the chancel could be a model for the simple beauties of the English country church. Right: The north door is, for once, not blocked by masonry in-fill. It still has a door but the blocking is achieved by a glass case containing remnants of previous churches here. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

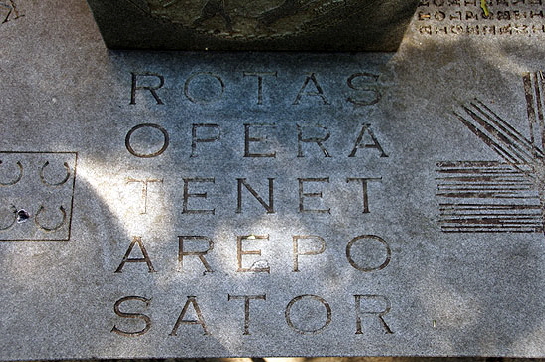

The “Millennium Bench”. How I loved this! The bench - let’s call it a memorial because that’s what it is really - has a who raft of fun things carved into it, including even games and puzzles! If we haven’t blown each other up in a thousand years time or been drowned by melting icecaps, our descendants will have fun with this. I am tempted to show the whole shebang but perhaps it will take up too much server space. it is, however, another example of the superb stewardship this church enjoys from its clergy, churchwardens and congregation. Left: The centrepiece is a kind of circular frieze of men hunting pheasants with dogs. Ok, so that’s not too typical of English life, perhaps. I find it an odd choice and some might find it controversial but if that’s representative of life in Luppitt then who are we to quibble? Right: The classic Greek magic square where the same words can be read in every direction. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

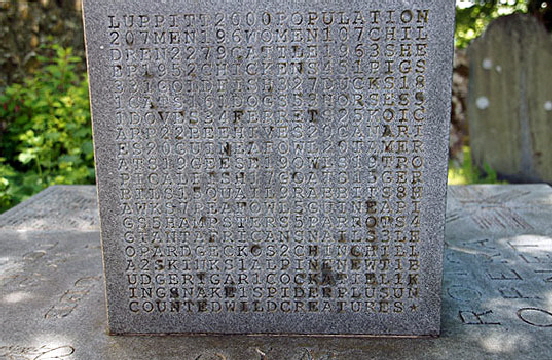

Left: This is my favourite bit. As well as recording the population of men, women and children we can find out that the village also had “1 Alpine Newt” and - omigod - “4 Giant African Snails”. The mind boggles. Sadly there were also “5 HamPsters”. Come on guys do you want your descendants to think that Luppitt-ites can’t spell? Cats outnumber dogs by 181 to 161 (hurrah!) despite the pheasant shooting. It’s a tie between guinea pigs and hamPsters at five - all. Right: It’s good to know that Moscow and Stonehenge are in the same general direction. Who would have guessed? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

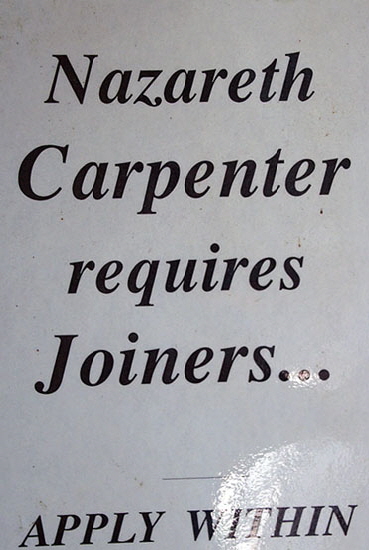

Left: The grave of Maj Gen George Arthur Cookson 1860-1929. He commanded part of the Indian Army in the days when it seemed the Sun would never set on the Empire. Centre: No comment required. How sad. Right: They have a sense of humour here. This notice in the porch tickled my fancy. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The soffits of the tower arch are decorated with a kind of niche design that I have never seen anywhere else. Right: The church from the north west. Note that on the north side the land is much higher than the level of the church this rendering the north door functionally useless. The Church Guide asks why this should be and says that the only explanation the author has heard is that this door was used only to allow the Devil out of the church during baptism. Well, that explanation is exactly right! Parishioners would not have ventured through the “Devil’s Door”. We no longer regard the rite of baptism as being also a form of exorcism so north doors are no longer needed. Some churches now use their north doors as the main entrance because we no longer have qualms about using them, but 90% or more of north doorways are either blocked by masonry or have doors that are never unlocked. So Luppitt with it’s unusable north door is in fact, proof of concept. It was palpably never designed to be used by people at all.. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Luppitt Grotesques. Left: Preserved within the glass case in the north doorway is this face that was probably a Norman corbel from the original church. Centre and Right: A couple of grotesques. They are gargoyle-like but it is not clear that they ever had any drainage function. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||