|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

or Norman influences on the island: the predominant influence would have been Irish Celtic with all the simplicity that that implies. The present church dates from around 1833. It is pleasing in its proportions with a polygonal apse and with two transepts that extend upwards to the roofline of the nave. The rendered exterior is a bit brutal in appearance. The interior is light and airy with that non-comformist look that is characteristic of the island churches. The shallow apse brings the altar close to the congregation. The west end is dominated by an impressive pipe organ. When we visited the church was being prepared for the Harvest Festival. It is a welcoming church without any of the pretentiousness that we often find in English Victorian churches, and the faux Gothic look is functional and restrained. It’s a nice place! The crosses date from the seventh to the twelfth centuries and were mainly discovered around the parish of Kirk Michael itself. Originally they were located within the lychgate but they were brought indoors to the north transept to better protect them from weathering. |

|

|

||

|

Left: The apse with its very simple altar table. The modern reredos has a faintly Orthodox look to it and shows the four evangelists flanking what the Church Guide calls “an ecclesiastical design”. No, I couldn’t make out what it is either! It is of oak on a gold background whereas the evangelists are painted in oils. Right: Looking towards the west and the impressive gallery and organ. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The collection of crosses in the north transept. Right: The war memorial on the north wall reminds us that the island’s special political status did not mean that it did not make the same sacrifices as the rest of the country. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

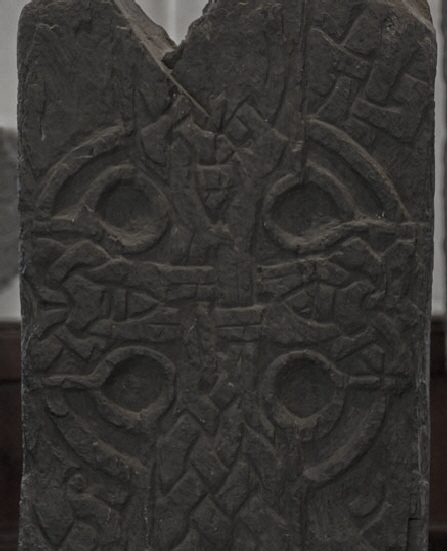

The Dragon Cross (Catalogue No 117). As with all of these descriptions, I am indebted to the free leaflet provided by the church and to publications by the Manx Museum. The Dragon Cross is so-named because of the dragon designs on the in-fills either side of the actual shaft of the cross. They have intertwined tails as can be seen in the (rotated) picture lower right. The spaces between the cross head and its enclosing circle are pierced whereas on many of the very early Celtic crosses (see Kirk Lonan) are unpierced. The dragon designs are decidedly Scandinavian in origin and this cross is believed to date from the early eleventh century. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

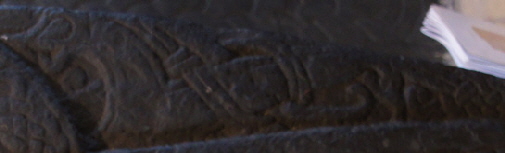

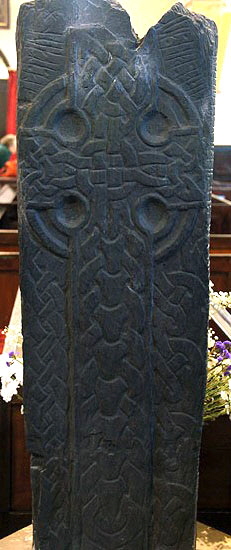

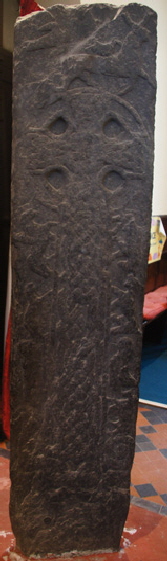

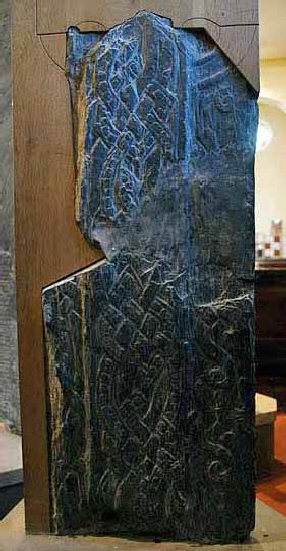

Left and Centre: Gaut’s Cross (No 101). This is an extraordinary piece. To the left and right of the cross head are runic inscriptions. There are others running up the sides. These proclaim “Gaut made this and all in Man”. In Kirk Andreas another cross proclaims “Gaut made (this) son of Bjorn from Kolli”. They are, of course, assumed to be by the same man, Gaut. His claim that he carved “all in Man” cannot be true of all of the crosses, of course, many of them centuries earlier than these but it is assumed that he refers to all runic crosses in this style. No others specifically bear his name but several others in the same style are assumed to be his. The cross here is a synthesis of Celtic and Scandinavian styles. The shaft has a tight interlaced pattern characteristic of the island and called the “ring chain” pattern. The full translation of the runes reveal “... Melbrigdi son of Athkan the smith erected this cross for his sin....soul but Gaut made it and all in Man”. These are, in fact, Celtic names so we know that the cross was commissioned by a Celt and executed by a Viking craftsman, demonstrating the assimilation of Vikings and their culture into the Celtic one on the island. Gaut’s design was widely copied by other craftsmen. Right: The Mal Lumkun Cross (No 130). This cross is decorated on just the one side but the reverse side (picture below) does have runes which read “Mael Lomchon raised this cross to the memonry of Mal Mura his foster mother daughter of Dugald the wife whom Athisl had” and then “Better is it to leave a good foster son than a bad son”. On the left and below the cross head is a hart seized by a hound. Less obvious on the right side is a hart seated with a man playing a harp. There is another figure with drinking horn. This is one of the Valkyrie making an offering to Bragi, the god of poery and inspiration. So here we have the clearest possible conjunction of Christian and Viking religious imagery. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The reverse side of the Mal Lumkun Cross with its runes. Centre: Dragon Fragment (No 116) from the early eleventh century. The head is of the dragon is bottom right of the fragment but you need to turn your head ninety degrees to the right to see it! The pear-shaped shape is the eye and there are fangs on the upper and lower jaws. This is believed to be by the same sculptor as the Dragon Cross above. Right: Gerth Fragment. The figure upper right is bird-shaped and is thought to represent the maid Gerth. Below her (you will need to twist your head again!) is a tethered horse belonging to the god Frey who wooed her. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The tethered steed from the Gerth Fragment. Right: Close up of the head of the Mal Lumkun cross. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

All Three Images Above: The Crucifixion Cross (No 129). This is only a fragment but it is a remarkable one. Apparently, kermode suggested it may have represented the Ascension. In the spaces above the cross in the left hand picture are a winged figure and a cock. The figure is thought to be an angel but juxtaposed with the cockerel might it not be St Peter? The reverse side of the cross (right) is not pictorial but its intricate interlaced work is very beautiful. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

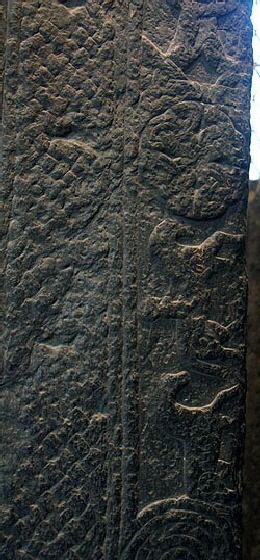

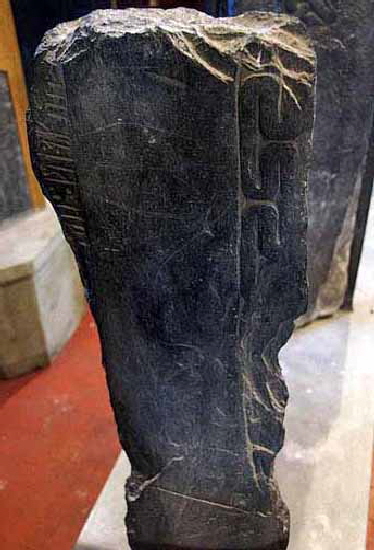

All Above: Joalf’s Cross (No 132). This massive cross (7ft high) is late tenth or early eleventh century. It is decorated on both sides with a long runic inscription along one edge. This is a beautifully decorated piece. Either side of the cross shaft are carved designs and hunting scenes. There are spiral volutes below the cross head. The runes say: “(Joalf) son of Thorolf the Red erected this cross to the memory of Frida his mother”. One side of the cross (second left) is believed to be by Gaut. Note the stag above the cross head being pursued by a hound. This cross is covered in symbols of the Viking way of life. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This crude warrior figure appears above the runes on Joalf’s Cross and is believed to represent Joalf himself. Centre and Right: Cross No 126. One face (centre) shows inly interlaced decorative designs but the other has a chain-ring design surrounded by figures. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

this cross treats us to all kinds of Norse characters as well as the Archangel Michael! The picture above left is Odin with his spear. |

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

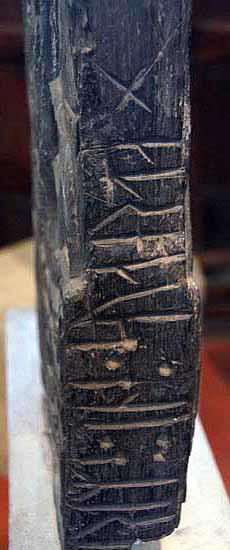

Left: Cross No 102. Centre: Deeply carved runes. Right: Close up of the runes on the Mal Lumkun cross. |

|||||||||||||||

|

Footnote - What are Runes? |

|||||||||||||||

|

Whole books have been written on this subject so this is just a brief description. Runes, as you can see in the pictures above, were a simple form of writing. Note that curves and circles play no part in runic scripts. Each rune is a variation on a vertical line. The reason for this is that they were intended to be inscribed mainly on wood - particularly on bark - and on stone. In the case of wood it was therefore possible to mostly carve along the grain, making the whole task so much easier. Ancient cuneiform script was also, by and large, based on straight lines although the characters were often much more elaborate than runic scripts. We might see runes as being a continuation of an age-old tradition of devising forms of writing designed to best fit the writing materials available. Cuneiform, for example, was used to carve on clay tablets with a stylus. As with so many things, runes have become the stuff of fantasy and mythology and so “rune” has become associated with any old pictorial alphabet real and imagined! In the western Roman Empire Latin gradually supplanted Greek and local Italian dialects. This was not a cultural imposition: rather that the various peoples that traded with Rome adopted it out of economic necessity. There is an obvious parallel in the modern world where vast swathes of the world’s population are learning English - or perhaps, more accurately, American! The eastern lands of the Roman Empire did not adopt Latin. It is important to remember this because it explains why the Gospels were written not in Latin as most people suppose but in Greek. After the division of the Empire, the Eastern Empire - later the Byzantine Empire - retained Greek as the language of administration and government. Many of the Germanic tribes defied incorporation into the Empire for centuries, of course, and eventually sacked Rome itself. As Rome’s foes they had no need to adopt Latin and they retained their Germanic languages. The Scandinavian races themselves were culturally and linguistically Germanic and, of course, were not at all involved with Rome. The Germanic people seemed to have started using runic script for communication from about AD150. It is believed that the Goths may have become familiar with writing through trade with Greek lands as long ago as the sixth century BC and, significantly, some of them formed the province that is still called Gothland in what is now Sweden. The Christianisation of Europe led to runes being steadily supplanted by Latin. Christianity, however, did not fully eradicate pagan beliefs in Scandinavia until as late as the twelfth century. The Manx crosses show us that even when Christianity was adopted, it did not immediately supplant the pagan gods: rather the Viking people assimilated Christianity and initially saw no contradiction in juxtaposing Christ and Odin in their belief system. Vikings did not worship their gods in the way monotheistic religions do; rather they propitiated and reached an accommodation with them. Perhaps the biggest myth in the history of Christianity in Britain and elsewhere is the concept that people became “converted” and promptly dropped all pagan beliefs and superstitions. Remember that the next time you see a Green Man grinning at you in a church and some fool tries to convince you that is has a Christian symbolism! Given all of this, the Vikings did not, of course, adopt Latin at all. Unsurprisingly then, they also hung onto runic script for much longer than in the rest of Europe. Interestingly, runes are also confined to certain areas of England. That seems to be connected to which of the so-called “Saxon” tribes colonised any given region. The Saxons themselves seem not to have used runes. The Jutes and the Angles did and so runes are most common in areas that they settled - East Kent and the North of England respectively. Kent, of course, was Christianised quite quickly since this was the stronghold of St Augustine’s mission from Rome. Other parts of the country hung onto runes much longer and, as we have seen, the Isle of Man was particularly isolated from Rome’s brand of Christianity and the Latin that was its principal language. Being Germanic peoples, it seems that Vikings and “Anglo-Saxons” were able in part to communicate with each other, so runes would have been very useful. There were, however, different varieties of runic alphabet although all of them share many of the “letters”. That’s not really surprising because this was a “folk” form of communication, not a scholarly one. The ones used in the Isle of Man originated in Norway and they are, therefore later than the Gothic runes which arrived in Kent via the Jutes in the 5th or 6th centuries and those found in Northumbria and Cumbria introduced by the Angles in the 7th century. You can see a fine example of Cumbrian runes on the Norman font at Bridekirk. |

|||||||||||||||